Human coronavirus HKU1

Human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1) is a species of coronavirus which originated from infected mice. In humans, infection results in an upper respiratory disease with symptoms of the common cold, but can advance to pneumonia and bronchiolitis.[1] It was first discovered in January 2005 in two patients in Hong Kong.[2] Subsequent research revealed it has global distribution and earlier genesis.

| Human coronavirus HKU1 | |

|---|---|

| |

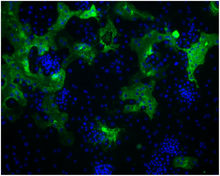

| Formation of HcoV-HKU1. | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Nidovirales |

| Family: | Coronaviridae |

| Genus: | Betacoronavirus |

| Subgenus: | Embecovirus |

| Species: | Human coronavirus HKU1 |

The virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the N-acetyl-9-O-acetylneuraminic acid receptor.[3] It has the Hemagglutinin esterase (HE) gene, which distinguishes it as a member of the genus Betacoronavirus and subgenus Embecovirus.[4]

History

HCoV-HKU1 was first detected in January 2005, in a 71-year-old man who was hospitalized due to acute respiratory distress syndrome and radiographically confirmed bilateral pneumonia. The man had recently returned to Hong Kong from Shenzhen, China.[5][2]

Virology

Woo, et al., were unsuccessful in their attempts to grow a cell line from HCoV-HKU1 but were able to obtain the complete genomic sequence. Phylogenetic analysis showed that HKU1 is most closely related to the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), and is distinct in that regard from the other known human betacoronaviruses, such as HCoV-OC43.[5]

When the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), spike (S), and nucleocapsid (N) genes were analyzed, incompatible phylogenetic relationships were discovered. Complete genome sequencing of 22 strains of HCoV-HKU1 confirmed this was due to natural recombination.[5] HCoV-HKU1 likely originated in rodents.[6]

HCoV-HKU1 is one of seven known coronaviruses to infect humans. The other six are:

- Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E)

- Human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63)

- Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43)

- Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV)

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1)

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

Epidemiology

A trace-back analysis of SARS negative nasopharyngeal aspirates from patients with respiratory illness during the SARS period in 2003, identified the presence of CoV-HKU1 RNA in the sample from a 35-year-old woman with pneumonia.[2]

Following the initial reports of the discovery of HCoV-HKU1, the virus was identified that same year in 10 patients in northern Australia. Respiratory samples were collected between May and August (winter in Australia). Investigators found that most of the HCoV-HKU1–positive samples originated from children in the later winter months.[8]

The first known cases in the Western hemisphere were discovered in 2005 after analysing older specimens by clinical virologists at Yale-New Haven Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut who were curious to discover if HCoV-HKU1 was in their area. They conducted a study of specimens collected in a 7-week period (December 2001 – February 2002) in 851 infants and children. Specimens of nine children had human coronavirus HKU1. These children had respiratory tract infections at the time the specimens were collected (in one girl so severe that mechanical ventilation was needed), while testing negative for other causes like Human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza viruses (types 1–3), influenza A and B viruses, and adenovirus by direct immunofluorescence assay as well as human metapneumovirus and HCoV-NH by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The researchers reported that the strains identified in New Haven were similar to the strain found in Hong Kong and suggested a worldwide distribution.[9] These strains found in New Haven is not to be confused with HCoV-NH (New Haven coronavirus), which is a strain of Human coronavirus NL63.

In July 2005, six cases were reported in France. In these cases, French investigators utilized improved techniques for recovering the virus from nasopharyngeal aspirates and from stool samples.[10]

References

- Lim, Yvonne Xinyi; Ng, Yan Ling; Tam, James P.; Liu, Ding Xiang (2016-07-25). "Human Coronaviruses: A Review of Virus–Host Interactions". Diseases. 4 (3): 26. doi:10.3390/diseases4030026. ISSN 2079-9721. PMC 5456285. PMID 28933406.

See Table 1.

- Lau, S. K. P.; Woo, P. C. Y.; Yip, C. C. Y.; Tse, H.; Tsoi, H.-w.; Cheng, V. C. C.; Lee, P.; Tang, B. S. F.; Cheung, C. H. Y.; Lee, R. A.; So, L.-y.; Lau, Y.-l.; Chan, K.-h.; Yuen, K.-y. (2006). "Coronavirus HKU1 and Other Coronavirus Infections in Hong Kong". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 44 (6): 2063–71. doi:10.1128/JCM.02614-05. PMC 1489438. PMID 16757599.

- Lim, Yvonne Xinyi; Ng, Yan Ling; Tam, James P.; Liu, Ding Xiang (2016-07-25). "Human Coronaviruses: A Review of Virus–Host Interactions". Diseases. 4 (3): 26. doi:10.3390/diseases4030026. ISSN 2079-9721. PMC 5456285. PMID 28933406.

See Table 1.

- Woo, Patrick C. Y.; Huang, Yi; Lau, Susanna K. P.; Yuen, Kwok-Yung (2010-08-24). "Coronavirus Genomics and Bioinformatics Analysis". Viruses. 2 (8): 1804–1820. doi:10.3390/v2081803. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 3185738. PMID 21994708.

In all members of Betacoronavirus subgroup A, a haemagglutinin esterase (HE) gene, which encodes a glycoprotein with neuraminate O-acetyl-esterase activity and the active site FGDS, is present downstream to ORF1ab and upstream to S gene (Figure 1).

- Woo, P. C. Y.; Lau, S. K. P.; Chu, C.-m.; Chan, K.-h.; Tsoi, H.-w.; Huang, Y.; Wong, B. H. L.; Poon, R. W. S.; Cai, J. J.; Luk, W.-k.; Poon, L. L. M.; Wong, S. S. Y.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J. S. M.; Yuen, K.-y. (2004). "Characterization and Complete Genome Sequence of a Novel Coronavirus, Coronavirus HKU1, from Patients with Pneumonia". Journal of Virology. 79 (2): 884–95. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005. PMC 538593. PMID 15613317.

- Fung, To Sing; Liu, Ding Xiang (2019). "Human Coronavirus: Host-Pathogen Interaction". Annual Review of Microbiology. 73: 529–557. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115759. PMID 31226023.

- Sloots, T; McErlean, P; Speicher, D; Arden, K; Nissen, M; MacKay, I (2006). "Evidence of human coronavirus HKU1 and human bocavirus in Australian children". Journal of Clinical Virology. 35 (1): 99–102. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.008. PMID 16257260.

- Esper, Frank; Weibel, Carla; Ferguson, David; Landry, Marie L.; Kahn, Jeffrey S. (2006). "Coronavirus HKU1 Infection in the United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (5): 775–9. doi:10.3201/eid1205.051316. PMC 3374449. PMID 16704837.

- Vabret, A.; Dina, J.; Gouarin, S.; Petitjean, J.; Corbet, S.; Freymuth, F. (2006). "Detection of the New Human Coronavirus HKU1: A Report of 6 Cases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 42 (5): 634–9. doi:10.1086/500136. PMID 16447108.

External links