Guyzance

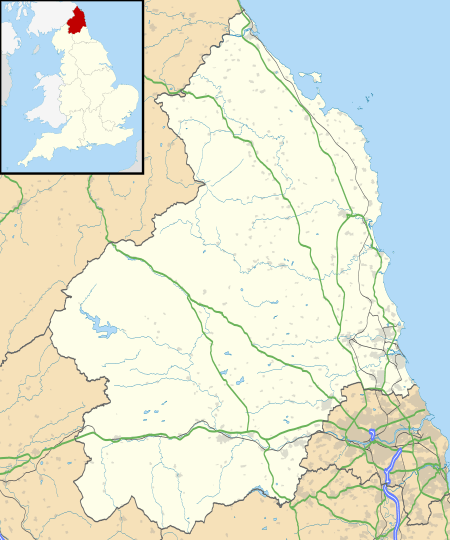

Guyzance, historically Guizance, is a small village or hamlet in Northumberland, England. It is located on the River Coquet, roughly 6 miles south of Alnwick and around 3 miles west of Amble. Guyzance is one of only two places in Great Britain with a -zance ending; the other is Penzance in Cornwall. The similar names are co-incidence however.

| Guyzance | |

|---|---|

Houses 1, 2 and 4 are on the north side of the main street in Guyzance | |

Guyzance Location within Northumberland | |

| OS grid reference | NU210039 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MORPETH |

| Postcode district | NE65 |

| Dialling code | 01245 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Northumberland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament | |

History

The name Guyzance is thought to be derived from a Norman family name "Guines", from an area of the same name near Calais. Other forms of the name recorded locally include "Gynis" (1242), "Gysnes" and "Gisyng".[1]

The village of Guyzance has existed since at least since 1242, when Robert de Hilton was its owner.[2] In 1147, a Premonstratensian Order priory was founded at nearby Brainshaugh.

In 1885, Guyzance was described thus in Whellan's History, Topography, and Directory of Northumberland:[3]

"GUYZANCE, or GUYSON, is a township and village in this Shilbottle parish, the property of the Duke of Northumberland; Robert Delisle, Esq. the heirs of the late Thomas Fenwick, Esq., and Thomas Tate, Esq. The rateable value is £l,671 10s., and the tithes, which are the properly of Thomas Tate, Esq., are valued at £130 per annum. The number of inhabitants in 1801, was 172; in 1811, 186; in 1821, 173; in 1831, 197; in 184l, 205; and in 1851, 213 souls. THE VILLAGE of Guyzance is situated seven miles south by east of Alnwick. There was formerly a priory here, which was annexed to Alnwick Abbey, by Eustace Fitz John. We find from Tanner's Monastica that it was endowed with a portion of the tithes, and two bovates of land, but as to any other portion of its history we possess no records. The remains of the old chapel are still here, with the burying ground, in which the Tate family are still interred. BANK HOUSE, the seat of Thomas Tate, Esq., is situated about a mile north of the village."

The present centre of the hamlet lies to the north of a large meander in the River Coquet, and there was settlement near the neck of the meander in medieval times. This is known as Guyzance in official records, and it is likely that the Norman settlement was located in this southern location, rather than the later northern one. The Prior of Brinkburn and the Abbot of Alnwick held part of the area in the 15th century, but this changed again with the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII. The nunnery was known as Gysnes, an early form of Guyzance, while the church was known as Gisyng, and although officially in the Chapelry of Brainshaugh, was normally referred to as Guyzance church. The mill to the west is also known as Guyzance Mill, and was first established around 1336, while the weir dates from around 1350. In 1472 ownership of the hamelt passed to the Percy family, owners of Warkworth Castle, while in 1567, William Carr of Whitton was recorded as the owner.[4]

By the 17th century, there were two rows of dwellings in Guyzance, and the common land had been enclosed by 1685. The evidence is not conclusive, but it would appear that the centre of the hamlet had moved northwards by this time, and the southern location abandoned. The Conservation Area Appraisal suggests that archaeological excavation might enable this uncertainty to be resolved.[5] Barnhill Farm was established in the early 18th century, and the farmhouse would be incorporated into Guyzance Hall in the 19th century. Park Mill iron and tin foundry was built in 1776, to the designs of John Smeaton, although the main building is known as the Dye House, following its reuse as a woollen mill from 1791. The large house at Brainshaugh was improved by the addition of garden walls, incorporating a privy, and Guyzance Mill was rebuilt by the Duke of Northumberland in the 1830s. The miller continued to live in the 16th-century mill house a little further to the north. The cottages in the main street were remodelled prior to the 1860s, a smithy was added to the west of the dwellings, and one of the cottages became a school in 1852.[6]

By the end of the 19th century, access to Guyzance from the south had been improved by the construction of a road heading southwards, which passed Guyzance Mill and crossed the river by a new bridge to the east of the woollen mill. Although the bridge is dated to around 1865,[7] and appeared on the 1897 Ordnance Survey map, it did not appear on the 1895 map.[8] The former track from the hamlet which crossed a ford over Quarry Burn to reach Guyzance Mill became a private road to Barnhill Farm, remodelled to become Guyzance Hall in the 1890s, and a footbridge made crossing the Quarry Burn rather easier.[9] In 1985 the Dye House was extended by the addition of two new bays, and in the late 20th century, cottages 3 and 4 were combined, three cottages opposite them became numbers 7 and 8, two new cottages were added to the north side of the street, some new houses were built near the Dye House, and the school became the village rooms.[10]

In 2008, the hamlet of Guyzance became a Conservation Area. Initial assessment was carried out by the North of England Civic Trust on behalf of Alnwick District Council in 2007. Consideration was given to designating a larger area, including Guyzance Bridge, the woollen mill site, the buildings at Brainshaugh and Guyzance Mill, but after consultation, the restricted area immediately around the main street, Barnhill Farm and Guyzance Hall was so designated.[11] The River Coquet and its environs at Guyzance is part of a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), which protects it from inappropriate development.[12] The hamlet is part of the Warkworth Ward, and under the governance of Alnwick District Council. No separate population statistics are kept; the population of the ward was 1,960 in 2008, but most of those lived in Warkworth, with only a small number living in Guyzance.[13]

Buildings

The village consists of one small street of single-storey facing cottages, and a number of scattered cottages, farms and large houses. Numbers 1, 2 and 4 are at the east end, on the north side of the street, and form a single terrace. They date from the 18th century, but were remodelled in the 19th century. There was formerly a fourth cottage, No. 3, but this has been incorporated into No. 4, and its front door blocked up. The left hand end wall of No. 4 includes two blind windows and there is a Victorian post box built into it.[14] After two more recent cottages is the old school, which was probably originally a cottage, and is now the village rooms. It also dates from the 18th century, and was remodelled in 1852.[15] Attached to the old school and the final building on the north side of the road is No. 5 and an adjoining former joiners shop, which were built and remodelled at similar times to numbers 1 to 4.[16] Crossing to the south side of the road, No. 6 is opposite the old school, and has a similar history.[17] After a gap, numbers 7 and 8 are opposite numbers 1 to 4. They were originally a row of three cottages, built and remodelled as the same time as the others, but reduced from three to two dwellings in the 20th century.[18] To the rear of No. 8 are some 18th century outbuildings, with attached pigsties, privies and middens, which were altered in the 19th century. The main building contains three blacksmith's windows. All of the buildings and their associated garden walls are grade II listed.[19]

Guyzance Hall is a grade II listed structure. It was built as a farmhouse for Barnhill Farm around 1800, but was extended to become a country house in 1894, when the architect William Henry Knowles designed major extensions for the owner J D Milburn. This included a range with a ballroom, built in neo-Tudor style, and the same style was used for a tower added in 1920.[20] The hall, which sits in 400 acres (160 ha) of land, has 15 bedrooms and was bought by the Rev. Robert Parker in 2008. It became a popular venue for weddings, and Parker sold it for around £6 million in 2016, only retaining a cottage in the grounds for his personal use.[21] The estate has two lodges, and the west lodge, which was built to an "L"–shaped plan in the early 20th century is also grade II listed. It is a single storey building in free Tudor style, although parts of it have a basement.[22] Some 130 feet (40 m) to the east is an arched bridge, built of rock-faced stone with cast iron and wrought iron posts and chains. It was constructed at a similar time to the lodge, and carries the drive over Quarry Burn.[23]

To the south of the housing are the remains of a chapel. The nave dates from the 11th or 12th centuries, while the chancel dates from the 13th or 14th centuries. The floor of the building is covered with concrete paving added in the 19th century, and there is a memorial to the Tate family dated 1864. There was a Premonstratensian nunnery in the vicinity, founded by Richard Tison in the 12th century, but it had become disused by about 1500, and became a parochial curacy. It is unclear whether the ruins were part of the nunnery or not, as a monastery church and a church of Guyzance are mentioned in early documents, and the ruins could be either. In addition to being grade II* listed, the site is also a scheduled ancient monument.[24]

Guyzance Mill, a ruined 19th century water powered corn and feed mill is located on the west bank of the river, with a large dam built across the channel. The iron and timber undershot water wheel is internal to the building, but was probably external when the mill was built. The building has three storeys, and despite its condition, still has some stones, gearing and machinery in position.[25] The present building is not the first on the site, as a mill at this location was documented in 1336, and it may have also been a fulling mill at one point.[26]

Some 380 yards (350 m) upstream from Guyzance Bridge, and just above the confluence of the Hazon Burn with the River Coquet, is a horseshow dam built by the civil engineer John Smeaton in 1775. His clients were Edward Cook of Brainshaugh and John Archbold of Acton. The downstream face, which is 8 feet (2.4 m) high, is vertical and constructed of squared stone. The curved dam has a radius of 170 feet (51.8 m) and fed a millrace on the south bank of the river.[27] The water powered Acklington Park Iron and Tin Works, but this did not last long, and John Reed converted the building into a woollen mill in 1791. It ceased to be used for this purpose in 1884, and was derelict until 1915, when Ellwood Holmes from Newcastle used it to make hydrate of alumina. It was one of the first factories to be powered by hydroelectricity, after Holmes had a Gilks water turbine fitted into the millrace. This operation was also fairly short-lived, as the Duke of Northumberland refused to renew the lease in 1930 following pollution of the river. The building was converted into flats in 1968.[28] The bridge at the eastern end of the site was built around 1865. It has three segmental arches, constructed of rock-faced stone, and is also grade II listed.[29]

Around a mile north of the main street lies Bank House Farm. Originally a stone-built Victorian farm, the property was converted into a number of smaller residences in the 1990s. On the west side lies the original farmhouse and several smaller buildings, all of which have now been converted into twelve separate holiday lets. Over the road on the east side are a number of old outbuildings which, alongside some newer builds, now make up several permanent residences. Over the field to the east of the main farm also lies a row old agricultural workers houses, known as Bank House Cottages.

The Guyzance Tragedy

Feb2007.jpg)

On 17 January 1945, ten soldiers drowned while taking part in a military exercise at Guyzance,[30] on the River Coquet. The river was in full flood and their boat was swept over Smeaton's weir, after which it capsized. The men, all aged 18, were weighed down by full combat gear.[31] In 1995, a memorial service was held to mark the 50th anniversary of the tragedy and a plaque was unveiled. The campaign for a memorial had been spearheaded by Burnett Seyburn, who had been a lance corporal at the time of the original tragedy, and Vera Vaggs, a Northumbrian historian. As well as raising money locally, they obtained support from the National Lottery, the War Graves Commission, local landowner Sir Anthony Milburn and the Asda supermarket chain.[32]

Bibliography

- ADC (February 2008). Guyzance Conservation Area (PDF). Alnwick District Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- ADC 2008, p. 11.

- "Guyzance medieval village (Acklington)". Keys to the Past. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Brian Pears; et al. (2006). "GENUKI: Guizance, Northumberland Genealogy". GENUKI. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- ADC 2008, pp. 11-12.

- ADC 2008, pp. 12, 17.

- ADC 2008, p. 13.

- Historic England. "Bridge over River Coquet (1041925)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "1:2500 map, 1895 and 1897". Ordnance Survey.

- ADC 2008, p. 15.

- ADC 2008, p. 16.

- ADC 2008, pp. 6-9, 45.

- ADC 2008, p. 41.

- ADC 2008, p. 8.

- Historic England. "1 2 and 4 Guyzance Village (1153753)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Historic England. "The old school (1371115)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Historic England. "No. 5 and former joiners shop on west (1371131)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Historic England. "6 Guyzance Village (1371132)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Historic England. "7 and 8 Guyzance Village (1041889)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Historic England. "Outbuilding group to south of numbers 7 and 8 (1041890)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Historic England. "Guyzance Hall and East Wing Cottage (1304198)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Steafel, Eleanor (15 May 2016). "Meet Britain's richest vicar". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018.

- Historic England. "West Lodge Guyzance Hall (1304167)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Historic England. "Bridge over Quarry Burn (1041928)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Historic England. "Ruins of church or chapel (1153531)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Historic England. "Guyzance Mill Acklington (1041924)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- "Northumberland Watermills". North East Mills. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Historic England. "Dam upstream of Guyzance Bridge (1153600)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Historic England. "The Dye House (1041926)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Historic England. "Bridge over River Coquet (1041925)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Les Hull (2007). "Memorial to the Guyzance Tragedy". geograph. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- "Guyzance Tragedy". Amble and District Local History. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Webber, Chris (10 January 2015). "Tragedy of 10 soldiers who died on river". Northern Echo.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guyzance. |

- A Millers Tale at the SINE Project Website.