Gossler family

The Gossler family (also spelled Goßler, historically also Gosler), including the Berenberg-Gossler branch, is a Hanseatic and partially noble banking family from Hamburg.

The family is descended from weavers and burghers in the city-republic of Hamburg, and rose to great prominence in Hamburg in the late 18th century as a result of Johann Hinrich Gossler's marriage to Elisabeth Berenberg, the last member of the Belgian-origined Berenberg family and the sole heir to Berenberg Bank. Through marriage, the family thus became the main owners of the bank, which has legally been named Joh. Berenberg, Gossler & Co. since 1791. Since the late 18th century the family has been widely regarded as one of the two most prominent Hanseatic families of Hamburg, alongside the closely related Amsinck family.[1] A branch of the Gossler family was granted the name Berenberg-Gossler by the Hamburg Senate in 1880 and was later—controversially in the republic of Hamburg, which did not recognise the concept of nobility—conferred baronial rank by the Kingdom of Prussia.

Several family members served as senators in Hamburg in the 19th and early 20th century, and Hermann Gossler was head of state in 1874. Richard J. Evans describes the family as one of Hamburg's "great business families."[2] The Gossler Islands in Antarctica are named in honour of the family.

History

The family's earliest known ancestor Claus Gossler (1630–1713), who was most likely a velvet weaver, was a burgher of Hamburg from 1656 and lived in the parish of St. Catherine. He was the father of, among others, Daniel, David, Albert and Jacob Gossler (1666–ca. 1732), who all became velvet weavers and Hamburg burghers. Jacob Gossler had nine children, among them Johann Eybert Gossler (1700–1776), who was an accountant and a Hamburg burgher, and who bought the ceremonial office of Herrenschenk (i.e. cup-bearer; master of ceremonies of the Hamburg council) in 1739.[3]

Johann Eybert Gossler was the father of, among others, the banker Johann Hinrich Gossler (1738–1790) and Johann Jacob Gossler (1758–1812), who served as a French colonel during the Napoleonic Wars and who died during the French invasion of Russia.

The Gossler (Berenberg-Gossler) banking family

The banker Johann Hinrich Gossler (1738–1790) started as an apprentice at Berenberg Bank; after marrying the sole heir to the company, Elisabeth Berenberg (1749–1822), he was named a partner in 1769 by his father-in-law Johann Berenberg and became the bank's sole owner upon the latter's death in 1772. In 1788 Gossler accepted his own son-in-law L.E. Seyler as a partner. Seyler was married to Anna Henriette Gossler, the eldest daughter of Johann Hinrich Gossler and Elisabeth Berenberg, and became head of Berenberg Bank in 1790.

Johann Hinrich Gossler's son Johann Heinrich Gossler (II) became a partner in 1798 and served as a Hamburg Senator from 1821. He eventually succeeded his brother-in-law Seyler as head of Berenberg Bank, and was in turn succeeded as head of the company by his own son Johann Heinrich Gossler (III), who also served as consul-general of Hawaii. The latter's brother Hermann Gossler was a lawyer and senator and served as First Mayor and President of the Senate, i.e. head of state of the city-republic, in 1874.[4][3]

In 1880 Johann (known as John) Berenberg Gossler, longtime head of Berenberg Bank and son of Johann Heinrich Gossler (III), was granted the name Berenberg-Gossler by the Hamburg Senate. He was ennobled by Prussia in 1889 and granted the title of Baron by the Prussian king in 1910;[5] the ennoblement was controversial in the strictly republican city-republic of Hamburg, where nobility did not exist and where (foreign) nobles were traditionally barred from holding political office and even from owning property;[6] according to Richard J. Evans, "the wealthy of nineteenth-century Hamburg were for the most part stern republicans, abhorring titles, refusing to accord any deference to the Prussian nobility, and determinedly loyal to their urban background and mercantile heritage."[7]

One of Baron Johann von Berenberg-Gossler's sons, John von Berenberg-Gossler, served as a Hamburg senator 1908–1920 and as German Ambassador to Rome 1920–1921. John's younger brother, Baron Cornelius von Berenberg-Gossler, succeeded his father as head of Berenberg Bank in 1913. He was succeeded by his son, Baron Heinrich von Berenberg-Gossler in 1932; Heinrich von Berenberg-Gossler also served as consul general of Monaco.

The Gossler Islands in Antarctica and Gossler's Park in Hamburg are named for the family.

Wilhelm Gossler (1811–1895) was the grandfather of the painter and sculptor Mary Warburg, who was married to the art historian and cultural theorist Aby Warburg, a member of the Warburg banking family.

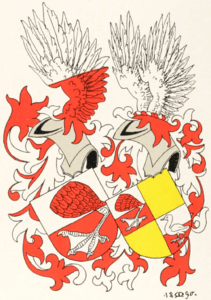

Coat of arms

The coat of arms adopted by Johann Hinrich Gossler in 1773 to the left; the "improved" coat of arms used from 1832 to the right

The coat of arms adopted by Johann Hinrich Gossler in 1773 to the left; the "improved" coat of arms used from 1832 to the right The combined arms of the Berenberg and Gossler families, used by the baronial Berenberg-Gossler family branch and as the logo of Berenberg Bank

The combined arms of the Berenberg and Gossler families, used by the baronial Berenberg-Gossler family branch and as the logo of Berenberg Bank

References

- Predöhl, Andreas, Das Ende der Weltwirtschaftskrise, Reinbek, 1962

- Richard J. Evans, "Family and Class in Hamburg," in D. Blackbourn (ed.), The German Bourgeoisie, p. 122, Routledge, 1993

- "Genealogie der Familie Gossler," in: Vierteljahrsschrift für Heraldik, Sphragistik und Genealogie, vol. 9, pp. 17–25, 1881

- "Gossler," Deutsches Geschlechterbuch, Vol. 127. Starke, Limburg an der Lahn 1961

- "Berenberg-Gossler," Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, vol. 16, Freiherrliche Häuser B II, C. A. Starke Verlag, Limburg (Lahn) 1957

- Renate Hauschild-Thiessen: "Adel und Bürgertum in Hamburg." In: Hamburgisches Geschlechterbuch. 14, 1997, p. 30.

- Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830–1910, Oxford, 1987, p. 560