Gnawa

The Gnawa (or Gnaoua, Ghanawa, Ghanawi, Gnawi'; Arabic: ڨناوة ) are an ethnic group inhabiting Morocco in the Maghreb.

The name Gnawa had probably originated in the indigenous language of North Africa and the Sahara Desert . The phonology of this term according to the grammatical principles of Berber is as follows: agnaw (singular), ignawen (plural), which means slave.

Gnawa was inscribed in 2019 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity[1]

History

The Gnawa population is generally believed to originate from the Sahelian region of West and Central Africa which had long and extensive trading and political ties with Morocco[2][3] The Gnawa are an ethnic group who were brought to Northern parts of North Africa by the Europeans as slaves, their ancestry is traced to southern regions of Morocco and sub saharan Africa. After the Islamization of the Berber and the abolition of slavery, they became a part of the Sufi order in Maghreb.[4] While adopting Islam, Gnawa continued to celebrate ritual possession during rituals where they are devoted to the practice of the dances of possession and fright. This rite of possession is called Jedba (Arabic: جدبة).

Gnawa and music

Gnawa music mixes classical Islamic Sufism with pre-Islamic African traditions, whether local or sub-Saharan. The term Gnawa musicians generally refers to people who also practice healing rituals, with apparent ties to pre-Islamic African animism rites. In Moroccan popular culture, Gnawas, through their ceremonies, are considered to be experts in the magical treatment of scorpion stings and psychic disorders. They heal diseases by the use of colors, condensed cultural imagery, perfumes and fright.

Gnawas play deeply hypnotic trance music, marked by low-toned, rhythmic melodies played on a skin-covered lute called sintir or guembri, call-and-response singing, hand clapping and cymbals called krakeb (plural of karkaba). Gnawa ceremonies use music and dance to evoke ancestral saints who can drive out evil, cure psychological ills, or remedy scorpion stings.

Gnawa music has won an international profile and appeal. Many Western musicians including Bill Laswell, Brian Jones, Randy Weston, Adam Rudolph, Tucker Martine, Robert Plant, Jacob Collier and Jimmy Page, have drawn on and collaborated with Gnawa musicians such as Mahmoud Guinia. Some traditionalists regard modern collaborations as a mixed blessing, leaving or modifying sacred traditions for more explicitly commercial goals. International recording artists such as Hassan Hakmoun have introduced Gnawa music and dance to Western audiences through their recordings and concert performances.

The centre for Gnawa music is Essaouira in the southwest of Morocco where the Gnaoua World Music Festival is held annually. The Gnawa of Marrakesh hold their annual festival at the sanctuary of Moulay Brahim in the Atlas Mountains.

The Gnawa of Khamlia hold their annual festival in August at the village Khamlia in Erg Chebbi.[5]

- Gnaouas from Oran (Algeria) with their guembri.

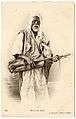

Gnaoua in a North African Interior

Gnaoua in a North African Interior Gnawa from Algiers with his guembri (circa 1906) by Jean Geiser (1848-1923).

Gnawa from Algiers with his guembri (circa 1906) by Jean Geiser (1848-1923). Gnawas circa 1920s

Gnawas circa 1920s Music Teacher

Music Teacher

Gnawa Musicians, by Harry Humphrey Moore.

Gnawa Musicians, by Harry Humphrey Moore.

References

- "UNESCO - Decision of the Intergovernmental Committee: 14.COM 10.B.26". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Amraoui, Ahmed El. "Gnawa music: From slavery to prominence". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Sinclair, Mandy. "A Brief History Of Gnaoua Music In Morocco". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- "Yobadi, friendship through Music". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "Les Gnaouas - Histoire et Culture | Holidway Maroc". Holidway (in French). 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gnawa. |

On-line sources

- Ibiblio.org: Gnawa Stories: Mystical Musician Healers from Morocco

- gnawa at the Moroccan ministry of Communication website

- WorldMusicCentral.org

- PTWMusic.com: gnawa by Chouki El Hamel at Duke University December 1, 2000

- Etymology of "Gnawa" from Encyclopædia Britannica

- Ben Saidi, A (2003) Amazigh Kateb Yassin discusses Maghreb Blues and Ghanawa Music-a diffusion of Berber, Arabic genres

Books

- Bernasek, L & Burger, H. S. (2008) Imazighen!: Beauty and Artisanship in Berber Life, Peabody Museum Press

- Courtney-Clarke, M & Brooks, G. (1996) Imazighen: The Vanishing Traditions of Berber Women, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London, UK

- El-Ghissassi, H. (2006) Regard sur Le Laroc de Mohamed VI, Michel Lafon

- Ennaji, M (2005) Multilingualism, Cultural Identity and Education in Morocco, Springer, New York, USA

- Harris, W. (2003) Morocco that Was, Eland Books, London, UK

- Hart, D.M. (2000) Tribe and Society in Rural Morocco, Frank Cass Publishers

- Howe, M (2005) Morocco: The Islamist Awakening and Other Challenges, University of Oxford Press, New York, USA

- Hoffman, K.E. (2008) We Share Walls: Language, Land, and Gender in Berber Morocco, Wiley-Blackwell

- Maxwell, G (2000) Lords of the Atlas, Weidenfeld & Nicolson Illustrated

- Maxwell, G (2002) Lords of the Atlas: The Rise and Fall of the House of Glaoua 1893–1956, The Lyons Press

- McKissack, F. & McKissack, P. (1995) The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa, Henry Holt and Co. LLC

- Pennell, C.R. (2003) Morocco: From Empire to Independence, OneWorld Publications

- Pennel, C.R. (2001) Morocco since 1830: A History, NYU Press, USA

- Porch, D (1983) The Conquest of Morocco - The Bizarre History of France's Last Great Colonial Adventure, the Long Struggle to Subdue a Medieval Kingdom By Intrigue and Force of Arms 1903–1914, Knopf

- Porch, D, 2nd Ed (2005) The Conquest of the Sahara, Ferrar, Straus & Giroux

- Rogerson, B & Lavington, S Edited by (2004) Marrakech, The Red City: The City through Writers' Eyes, Sickle Moon Books

External links

- Gnawa.net

- http://www.vodeo.tv/4-33-3982-des-gnawa-dans-le-bocage.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070929102727/http://www.editions-harmattan.fr/index.asp?navig=catalogue&obj=video&no=1052

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070928063425/http://prep-cncfr.seevia.com/idc/data/Cnc/Recherche/fiche2.asp?idf=3313

- Essaouira at WorldMusicCentral.org

- gnawa at brickhaus.com

- Gnawa Music