Glenwood Cluster

The Glenwood Cluster is a region in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests recognized by The Wilderness Society for its rich biodiversity, scenery, wildflower displays, cold-water trout streams and horse trails. It offers a unique habitat for rare plants, salamanders and other rare species. The Blue Ridge Parkway and the Appalachian Trail traverse the area, giving ready access with views to the east of the Piedmont region and to the west of the Valley of Virginia.[1][2]

| Glenwood Cluster | |

|---|---|

IUCN category VI (protected area with sustainable use of natural resources) | |

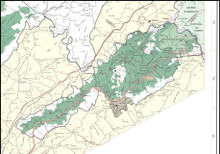

Location of Glenwood Cluster in Virginia | |

| Location | Bedford Botetourt Rockbridge, Virginia, United States |

| Coordinates | 37.55417°N 79.47368°W |

Description

The region includes wilderness areas protected by Congressional action, inventoried wilderness, and uninventoried areas recognized by the Wilderness Society as worthy of protection from timbering and roads.[1] A corridor along the Blue Ridge Parkway, managed by the National Park Service, and forest service land in the Glenwood Ranger District act as a buffer for the protected areas.

The following areas are in the cluster:[1]

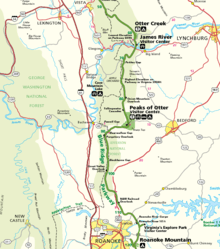

Location and access

Flanking the Blue Ridge Parkway, the region is south and east of the James River where the river turns east to cut through the Blue Ridge Mountains. It is 20 miles northwest of Roanoke, Virginia and about two miles southeast of Glasgow, Virginia.

Interstate 81 parallels the area on the west and Va 122 on the east. The section of the Blue Ridge Parkway travelling through the cluster can be accessed from US 501 on the north and VA 43 on the south. Other roads in the area are shown on National Geographic Map 789, Lexington and Blue Ridge Mountains.[3] The Blue Ridge Parkway, completed in 1935, follows the mountain tops at an average elevation of 3000 feet, giving access to scenic overlooks and natural areas along the way.[4]

Recreation areas in the Glenwood District include Cave Mountain Lake Recreation Area, a campground 8 miles south of Natural Bridge, Middle Creek Picnic Area, about 7 miles west of Buchanan, North Creek Campground, about seven miles from Buchanan, and the Locher Tract, a primitive picnic area about seven miles east of Natural Bridge. The Glenwood Information Center is in Natural Bridge, Virginia and the ranger’s district office is 1.5 miles south of Natural Bridge.[5]

Appalachian Trail

The Appalachian Trail extends for 2185 miles from Mount Katahdin in Maine to Springer Mountain in Georgia. A 43 mile section of the trail passes through the cluster from its crossing of the James River on the north to VA 43 on the south.[6] The route is indicated by a red-dashed line on the map of the cluster on this page. A high resolution map of the cluster is obtained by selecting the icon in the lower right of the window, then clicking on the map. The map shows side trails and shelters along the trail.

The trail can be broken into the following sections, with a link to access and parking information:[6]

Blue Ridge Parkway

The Blue Ridge Parkway connects the Skyline Drive on the north with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park on the south. From its low point at the James River with an elevation of 649 feet, it climbs to an elevation of 3950 feet at Apple Orchard Mountain. The road, with no stop-signs or billboards, is a scenic drive connecting overlooks to the west and east. Its construction overcame steep terrain, eroded mountainsides, granite and gneiss bedrock and extreme winter weather. Stonemasons from Italy and Spain built the sturdy walls and bridges still seen today. After legislation authorizing construction was passed in 1936, the highway was finished 51 years later in 1987. The highway, administered by the National Park Service, is closed when snow and ice create driving hazards.[5]

To maintain the rural views along the road, the National Park Service works with landowners of adjacent property and coalitions of citizens and state organizations to maintain visual guidelines. Support groups include Friends of the Blue Ridge Parkway and the Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation.[5]

Geologic history

The geology of the Glenwood Cluster has evolved over hundreds of millions of years. During this time, oceans were formed, each leaving a layer of sediment on its ocean bed. These ocean beds would be layered on top of one another, except for stress in the earth's crust that created folds pushing the beds on top of one another. The result has left a challenge for geologists to determine the history of rock now found in the area. There is general agreement that the rocks in the Blue Ridge are the oldest rocks in the state, some being formed at least 1.8 billion years ago.[7]

The landforms in Virginia are part of five provinces—the Appalachian Plateau, Ridge and Valley, Blue Ridge, Piedmont and Coastal plain. The Glenwood Cluster is located in the Blue Ridge Province, with the Piedmont Province to the east and the Ridge and Valley to the west. The Blue Ridge, the easternmost of the Appalachian Mountains, extends from Georgia to Pennsylvania, with widths ranging from 5 to 50 miles (8.0 to 80.5 km). In some places the province is a single ridge, while in other places it is a complex of closely spaced ridges. Rocks include Precambrian granite, gneiss, and metamorphosed volcanic rock of the late Precambrian.[8]

James River

One of the major river systems draining Virginia, the James River has formed large fluvial landscapes within the physiographic provinces of the Ridge and Valley Appalachians, the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Piedmont, and the Atlantic coastal plain. Water and sediments, collected from the large watershed of the James, are transported across the grain of the rock-controlled Ridge-and-Valley and Blue-Ridge provinces to downstream valleys now containing the signature of the evolution of the landscape in the river's watershed over millions of years.[9]

Beginning at the junction of the Cowpasture and Jackson rivers in the Allegheny Mountains of western Virginia, the James River flows for about 340 miles (550 km) to Chesapeake Bay, where it has become 5 miles (8 km) wide. The course of the river was formed over hundreds of millions of years as it followed faults in the earth's crust. Over time, it cut through 1,700 feet (520 m) of an ancient ocean's sediment to reach a bedrock of quartzite in the present-day Blue Ridge Mountains, creating a gorge through which the river now flows to reach Chesapeake Bay.[10]

Natural history

Clusters of wild areas, such as the Glenwood Cluster, are important for the maintenance of biological diversity. A natural landscape contains a blend of ecosystems—mountain slopes, moist areas, soil types, temperatures—over which species can roam in their search for mates, foraging for food, and the avoidance of predators and other stress-inducing hazards. The construction of roads breaks up the landscape into islands which limit the free migration of forest species. Such edge effects have been shown to minimize the diversity required for the maintenance of a rich biological habitat.[11]:109–114

The bird population is also affected by the division of undisturbed forest into islands with edges defined by roads. Predators of birds, such as raccoons, snakes, skunks, house cats and egg-eating crows and blue jays, are often found at forest edges. And roads provide a pathway for Brown-headed cowbirds in their search for the location of nests of smaller birds, who then destroy the eggs and replace them with their own eggs leaving the unwitting owner to raise the cowbird hatchlings.[11]:118

The Glenwood Cluster is divided by several roads, the largest being the Blue Ridge Parkway that divides the White Oak Ridge-Terrapin Mountain area from the rest of the cluster.[3]

The cluster contains pockets of old-growth forests, wild and complex mixtures of different species and ages of trees supporting a great diversity of organisms living in a relationship that has evolved over many centuries. As land is being developed, these forests are becoming rare. There are several pockets of old-growth forest in the cluster—the James River Face Wilderness contains as much as 100 acres (40 ha) of old-growth forest in a steep, rocky terrain that was difficult to log.[11]:124–125

Glenwood Ranger District

The Glenwood cluster lies within the Glenwood Ranger District of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest. The district has an area of 74,000 acres (300 km2), with a large part created from the Glenwood Estate lands.[12][5]:265 Forests in the area were cut and recut to supply charcoal for the production of pig iron. The Glenwood Furnace, in the Arnold Valley, was built in 1849 and last operated in 1876. Historical records indicate that the furnace employed 148 men, women and children in 1864.[6]:124

Old charcoal furnaces are part of the historic sites of the Glenwood Ranger District. Repeated cutting for the furnaces led in part to the successive forests that are present today. The early Glenwood purchase unit was composed of 60–90% American chestnut, a favored slope species by silvicultural techniques in 1914. A blight, discovered in 1912, progressed to the point that by 1922 foresters were salvaging the tree before its destruction by the blight. Pulpwood and extractwood contractors cut about 200,000 cords of wood on the Glenwood land between 1930 and 1950. The district sold almost 75,000 million board feet of chestnut in its first 38 years, and by 1951 only an estimated 4400 million board feet remained in the district.[13]

Other clusters

Other clusters of the Wilderness Society's "Mountain Treasures" in the Jefferson National Forest (north to south):

References

- Virginia's Mountain Treasures, report issued by The Wilderness Society, May, 1999

- Bamford, Sherman (February 2013). A Review of the Virginia Mountain Treasures of the Jefferson National Forest. Blacksburg, Virginia: Sierra Club, OCLC: 893635467.

- Trails Illustrated Maps (2007). Lexington, Blue Ridge Mts. Hiking Map (Trails Illustrated Hiking Maps, 789). Washington, D. C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1566952330.

- Blackwell, Mary Ellis; Causey, Anne Patterson (1999). Insiders Guide to Virginia's Blue Ridge (Ninth ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press. p. 359. ISBN 0-7627-3460-4.

- Winegar, Deane and Garvey (1998). Highroad Guide to the Virginia Mountains. Marietta, Georgia: Longstreet Press, Inc. pp. 247. ISBN 1-56352-462-7.

- Appalachian Trail Guide, Central Virginia (3rd ed.). Harpersville, West Virginia: Appalachian Trail Conference. 2014. pp. 118–163. ISBN 978-1-889386-88-1.

- Dietrich, Richard V. (1970). Geology and Virginia. Charlottesville, Virginia: The University Press of Virginia. p. 161.

- Hunt, Charles B. (1967). Natural Regions of the United States and Canada. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 260. ISBN 0-7167-0255-X.

- Bailey, Christopher M.; Sherwood, W. Cullen; Eaton, L. Scott; Powars, David S. (2016). The Geology of Virginia. Martinsville, Virginia: Virginia Museum of Natural History. p. 278. ISBN 1-884549-40-3.

- Deans, Bob (2007). The River Where American Began, A Journey Along the James. Lanham, Maryland: Bowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-5173-3.

- Nash, Steve (1999). Blue Ridge 2020. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4759-3.

- Bamford, Sherman (October 2014). 18 Wonders of Virginia. Richmond, Virginia: Sierra Club Virginia Chapter. p. 3. ISBN 0-926487-79-5.

- Sarvis, Will (2011). The Jefferson National Forest. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 1-57233-828-8.

Further reading

- Stephenson, Steven L., A Natural History of the Central Appalachians, 2013, West Virginia University Press, West Virginia, ISBN 978-1933202-68-6.

- Davis, Donald Edward, Where There Are Mountains, An Environmental History of the Southern Appalachians, 2000, University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia. ISBN 0-8203-2125-7.