Ghoraghat Upazila

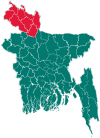

Ghoraghat (Bengali: ঘোড়াঘাট) is an Upazila of Dinajpur District in the Division of Rangpur, Bangladesh.[1]

Ghoraghat ঘোড়াঘাট | |

|---|---|

Upazila | |

Ghoraghat Location in Bangladesh | |

| Coordinates: 25°14.7′N 89°13′E | |

| Country | |

| Division | Rangpur Division |

| District | Dinajpur District |

| Area | |

| • Total | 148.67 km2 (57.40 sq mi) |

| Population (1991) | |

| • Total | 84,279 |

| • Density | 570/km2 (1,500/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| Website | Official Map of Ghoraghat |

Geography

Ghoraghat is located at 25.2458°N 89.2167°E . It has 17535 house holds and a total area of 148.67 km².

Administration

Ghoraghat thana was established in 1895 and was turned into an upazila in 1984. The upazila consists of 4 union parishads, One Paurashava, 115 mouzas and 111 villages.

Member of parliament: Md. Shibli Sadique.[2]

History

Ghoraghat was established in the time of Bakhtlar Khilji (see Blochmanu's Contr., J.A.S,1873, p. 215, Tabaqat-i-Nasiri, p. 156, Ain-i-Akbari, Vol. II, p. 135 and Vol. I, p. 370). After the historical conquest of Nabadwip from Lakshman Sen in 1203 and the conquest of principal city Gaur, Ikhtiyar al-Dīn Muḥammad Khalji left the town of Devkot in 1206 to attack Tibet, leaving Ali Mardan Khalji in Ghoraghat. The old Musalman military outpost of Deocote or Devkot near Gangarampur was in this Sarkar. As soon as the Muslims had made themselves masters of Gaur, they established two frontier posts, one at Dumdumma, on the bank of river Punarbhaba and another at Ghoraghat. A mosque in Dumdumma bears an inscription recording that it was built by Zafar Khan Bahram Iztin in the reign of Kai Kaos Shah in the year 697 A.H.(1297 AD).[3]

Ghoraghat was one of the 19 sarkars of Bengal. Sarkar was the administrative unit in the Mughal Empire of India. Raja Todar Mal, the Finance Minister of the Mughal empire during Akbar's reign divided Bengal into 19 sarkars to make the revenue collection easier. Ghoraghat Sarkar comprised South Rangpur, South-East Dinajpur and North Bogra. It had 84 mahals in its territory.[4] Later it became Chakla of Ghoraghat.The Sarkar produced much raw silk, revenue Rs.202,077.[5]

After the battle of Patna, 982 A.H.(1574 AD), when Daud retired to Orissa, (Badaoni, p. 184, Vol. II), his generals Kalapahar and Babu Mankli proceeded to Ghoraghat, (Badaoni, p. 192). Akbar's general, Majnun Khan, died at Ghoraghat.

Being the northern frontier district skirting Koch-Behar, numerous colonies of Afghan and Mughal chiefs were planted there under the feudal system, with large jagir lands under each. Bhim Narain, Rajah of Kuch Behar used to regularly pay tribute to the Emperor Shah Jahan, but that during the chaos which arose owing to Emperor's illness, and after the death of Sultan Shuja in February 1661 there was anarchy in the region. Bhim Narain became daring and refused to pay tribute and with a large force attacked Ghoraghat. In the same year (on 17th Rabiul-Awwal 1072 A.H) the Khan-i-Khinan (Muazzam Khan) set out from Khizapur (which has been identified to be a place close to Narayanganj) with war-vessels, for the conquest of Koch-Behar. The Rajah (Bhim Narain) fled to Bhutan, his minister Bholanath fled to the Murang, and the Imperialists stormed Kuch-Behar town, and named it Alamgirnagar.[5]

Archaeological Heritage

The shrine of Shah Ismail Ghazi is at Ghoraghat. He was a saint-warrior of the time of Ruknuddin Barbak Shah (1459-1474 AD). Shah Ismail Ghazi was first appointed to deal with the aggressive designs of the Orissan king Gajapati in the southern frontier of Bengal. He defeated Gajapati and wrested from him Mandaran, the frontier outpost. The successful general was then sent against Kamrup king Kameshwar, who was defeated and forced to pay tribute to the sultan. But soon, Bhandsi Rai, a commander of the frontier post of Ghoraghat, got jealous over the popularity and fame of Shah Ismail and sent a false report to the sultan that Ismail Ghazi, in collusion with the Kamrup king, was mediating to set up an independent kingdom for himself. The enraged sultan ordered the saint to be beheaded.

The Sura Mosque is situated in Ghoraghat-Panchbibi road. There is no inscription tablet at the mosque, but it has been dated to the early sixteenth century in the light of its close links with dated monuments of similar style. An inscription from the time of Alauddin Hussain Shah, dated at 910 A. H./1504 A. D. was discovered in the village Champatali, a few miles away from the place. It records the construction of a mosque, and if this inscription describes the mosque at Sura, the year 1504 A. D. is the date of its construction.[6]

Ghoraghat Fort Mosque situated in the southeastern corner of the Ghoraghat Fort, which is located on the right side of the river Karatoya in the southeastern part of the district of Dinajpur. Within the fort area were erected a number of religious and secular buildings, of which only a mosque in ruinous condition and a few scattered mounds have survived. According to an inscription the mosque was built in 1740-41 AD by Zainul Abedin, the Mughal fauzdar of the Sarkar of Ghoraghat.[7]

The Laldaha Beel is situated Ghoraghat thana Sadar west nort side of Kadim nagar and Lal bagg village. Many fairy tales are there about this beel.

Climate

The climate here is tropical. The summers here have a good deal of rainfall, while the winters have very little. This location is classified as Aw by Köppen and Geiger. The average temperature in Ghoraghat is 25.3 °C. August is the warmest month of the year. The temperature in August averages 28.9 °C. January is the coldest month, with temperatures averaging 18.0 °C. About 1902 mm of precipitation falls annually. The driest month is December, with 3 mm of rain. Most of the precipitation here falls in July, averaging 408 mm.[8]

| Climate data for Ghoraghat | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26 (79) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.5 (77.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

20.2 (68.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9 (0.4) |

13 (0.5) |

23 (0.9) |

64 (2.5) |

229 (9.0) |

373 (14.7) |

408 (16.1) |

333 (13.1) |

286 (11.3) |

149 (5.9) |

12 (0.5) |

3 (0.1) |

1,902 (74.9) |

| Source: | |||||||||||||

Education

Average literacy 26.1%; male 32.8%, female 19.2%.

Educational institutions: colleges 8, secondary schools 18, primary schools 53, brac schools 29, kindergartens 2, madrasas 34.

Noted educational institutions: Ghoraghat Govt. College (1984), Ghoraghat Women Degree College (1994), Raniganj Mahila College (1994), Dugdugirhat Technical College (2003), Raniganj Bilateral High School (1945), Chatsal Secondary School (1946), Balahar Secondary School (1958), Balagari' Secondary School (1966), Gopalpur Secondary School (1972), Krishnarampur Fazil Madrasa (1946), Deogaon Rahmania Senior Madrasa (1947), Nurjahanpur R.M.C.High School (1996), K.C. pilot High school and College, R.C. Pilot Girlhigh School, Ghoraghat Dakhil Madrasa, Shah Ismail Ghazi Girlhigh School, Ghoraghat Govt. Primary School, Dhakkhin Joydebpur Govt. Primary shchool."

Economy

Agriculture 68.64%, non-agricultural labourer 2.84%, industry 0.50%, commerce 12.95%, transport and communication 2.91%, service 4.35%, construction 0.53%, religious service 0.13%, rent and remittance 0.07% and others 7.08%.[9]

Health centres

Upazila health complex 1, union and family planning centre 4, satellite clinic 3.

Demographics

As of the 1991 Bangladesh census, Ghoraghat had a population of 84279. Males constituted 51.01% of the population, and females 48.99%. This Upazila's eighteen up population is 43913. Ghoraghat has an average literacy rate of 26.1% (7+ years), and the national average of 32.4% literate.[10]

Indigenous Communities

Santals, Mall Pahari, Bunna and Oraon are the indigenous groups living here for centuries. It is one of the region which was selected for implementation of development project called Santal Development Project (SDP).[12]

See also

- Upazilas of Bangladesh

- Districts of Bangladesh

- Divisions of Bangladesh

References

- Shamsuzzaman (2012), "Ghoraghat Upazila", in Sirajul Islam and Ahmed A. Jamal (ed.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- "Contact an MP". www.parliament.gov.bd. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- Calcutta Review. Calcutta University Press.

- "Sarkar - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- Salim, Ghulam Husain (April 1902). Riyazu-s-salatin; a history of Bengal. Translated from the original Persian by Maulavi Abdus Salam. Robarts - University of Toronto. Calcutta Asiatic Society.

- "Sura Mosque", Wikipedia, 2019-02-14, retrieved 2019-02-14

- "Ghoraghat Fort Mosque - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "Ghoraghat climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Ghoraghat weather averages - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "Ghoraghat Upazila - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "Population Census Wing, BBS". Archived from the original on 2005-03-27. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- "::Democracywatch-Advocacy and Awareness on good governance::". www.dwatch-bd.org. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- "Evalauation Report on Santal Development Project (SDP)". NoradDev. Retrieved 2019-02-14.