Shah Shuja (Mughal prince)

Shah Shuja (Bengali: শাহ সুজা, Urdu: شاہ شُجاع ),

(23 June 1616 – 7 February 1661)[1] was the second son of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan and Empress Mumtaz Mahal. He was the governor of Bengal and Odisha and had his capital at Dhaka, presently Bangladesh.

| Shah Shuja شاہ شُجاع | |

|---|---|

| Mughal Prince | |

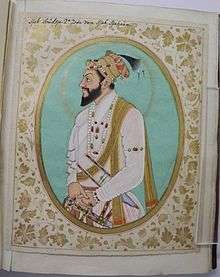

Portrait of Shah Shuja | |

| Born | 23 June 1616 Ajmer |

| Died | 7 February 1661 (aged 44) |

| Spouse | Bilqis Banu Begum Piari Banu Begum One another wife |

| Issue | Zain-ud-Din Mirza Zain-ul-Abidin Mirza Buland Akhtar Mirza Dilpazir Banu Begum Gulrukh Banu Begum Roshan Ara Begum Amina Banu Begum |

| House | Timurid |

| Father | Shah Jahan |

| Mother | Mumtaz Mahal |

| Religion | Islam |

Early life and family

Shah Shuja was born on 23 June 1616, in Ajmer. He was the second son and child of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan and his queen Mumtaz Mahal.

Shuja's siblings were Jahanara Begum, Dara Shikoh, Roshanara Begum, Aurangzeb, Murad Baksh, Gauhara Begum and others. He had three sons - Sultan Zain-ul-Din (Bon Sultan or Sultan Bang), Buland Akhtar and Zainul Abidin and four daughters - Gulrukh Banu, Roshanara Begum and Amina Begum.[2]

Personal life

Shah Shuja married firstly Bilqis Banu Begum, the daughter of Rustam Mirza, on the night of Saturday, 5 March 1633. The marriage was arranged by Princess Jahanara Begum. Rupees 1,60,000 in cash and one lakh worth lakh of goods were sent as sachak to the mansion of Mirza Rustam. On 23 February 1633, the wedding presents worth Rupees 10 lakhs were displayed by Jahanara Begum and Sati-un-nissa Khanum.[3] The following year she gave birth to a daughter, and died in childbirth. She was buried in a separate mausoleum named Kharbuza Mahal, at Burhanpur.[4] Her daughter was named Dilpazir Banu Begum by Shah Jahan,[5] and who died as an infant.

On the death of his first wife, he married Piari Banu Begum,[6] daughter of Azam Khan, second governor of Bengal during Shah Jahan's reign.[7][8] She was the mother of two sons, and three daughters,[9] namely, Prince Zain-ud-din Mirza born on 28 October 1639, Prince Zain-ul-Abidin Mirza born on 20 December 1645, Gulrukh Banu Begum (wife of Prince Muhammad Sultan), Raushan Ara Begum, and Amina Banu Begum.[10] In 1660, she fled to Arakan with her husband, sons, and three daughters. Shuja was murdered in 1661. His sons were put to death. Piari Banu Begum, and her two daughters committed suicide. The remaining daughter, Amina Banu Begum, was brought into the palace, where from grief she died an early death.[11][12] According to another source, one of Shuja's daughters was married to King Sanda Thudhamma. A year later he scented a plot and starved all of them to death, while his wife was in an advanced stage of pregnancy by himself.[13]

His third wife was the daughter of Raja Tamsen of Kishtwar.[14] She was the mother of Shahzada Buland Akhtar who was born in August 1645.[15]

Governor of Bengal

Shazada Muhammad Shah Shuja was appointed by Shah Jahan as the Subahdar of Bengal and Bihar from 1641 and of Orissa from 25 July 1648 until 1661. His father Shah Jahan appointed his deputy The Rajput Prince of Nagpur Kunwar Raghav Singh(1616-1671).[1] During his governorship, he built the official residence Bara Katra in the capital Dhaka.[16]

After the illness of Shah Jahan in September 1657, a power crisis occurred among the brothers. Shah Shuja proclaimed himself as Emperor, but Aurangzeb ascended the throne of Dehli and sent Mir Jumla to subjugate Shuja.[17] Shuja was defeated in the Battle of Khajwa on 5 January 1659.[1] He retreated first to Tandah and then to Dhaka on 12 April 1660.[1] He left Dhaka on 6 May and boarded ships near present-day Bhulua on 12 May heading Arakan.[1] Mir Jumla reached Dhaka on 9 May 1660 and was then appointed by Aurangzeb as the next Subahdar of Bengal.[17]

Construction projects in Dhaka

Bara Katra

Bara Katra

.jpg) An etching of Bara Katra by Sir Charles D'Oyly in 1823

An etching of Bara Katra by Sir Charles D'Oyly in 1823

Mughal war of succession

When Shah Jahan fell ill, a struggle for the throne started between his four sons - Dara Shikoh, Shah Shuja, Aurangzeb and Murad Baksh. Shuja immediately crowned himself the emperor and took imperial titles, November 1657.

He marched with a large army, backed by a good number of war-boats in the river Ganges. However, he was beaten by Dara's army in a hotly contested Battle of Bahadurpur near Banares (in modern Uttar Pradesh, India). Shuja turned back to Rajmahal to make further preparations. He signed a treaty with his elder brother Dara, which left him in control of Bengal, Orissa and a large part of Bihar, 17 May 1658.

In the meantime, Aurangzeb defeated Dara twice (at Dharmat and Samugarh), caught him, executed him on a charge of heresy and ascended the throne. Shuja marched again to the capital, this time against Aurangzeb. A battle took place on 5 January 1659 at the Battle of Khajwa (Fatehpur district, Uttar Pradesh, India) where Shuja was defeated.[18]

After his defeat, Shuja retreated towards Bengal. He was pursued by the imperial army under Mir Jumla. Shuja put up a good fight against them. However, he was finally defeated in the last battle in April 1660. After each defeat, he had to face desertions in his own army, but he did not lose heart. He, rather, reorganised the army with renewed vigor. But when he was going to be surrounded at Tandah, and when he found that reorganisation of the army was no longer possible, he decided to leave Bengal for good and take shelter in Arakan.

Military promotions

- 1636 - 5000(20)

- 1641 - 30,000(25)

- 1646 - 36,000(30)

- 1653 - 40,000(37)

- 1655 - 43,000(39)

Asylum in Arakan

En route to Arakan

Shuja left Tandah with his family and retinue in the afternoon of 6 April 1660 and reached Dhaka on 12 April. After remaining for a month, they departed the city and boarded Arakanese ships on 12 May at Bhulua (near present-day Noakhali, Bangladesh). The party first arrived at Chittagong and remained for some time. From here, they took the land route to Arakan, which is still called Shuja Road. Thousands of palanquins were used to carry Shuja's harem, and he himself performed Eid prayers at an Eidgah in Dulahzara.[19]

Death and aftermath

Shuja and his entourage arrived in Arakan on 26 August 1660,[20] and were greeted at the capital, Mrauk U, with courtesy. The Arakanese king, the powerful Sanda Thudhamma, had previously agreed to provide ships for Shuja and his family to travel to Mecca, where the prince had planned to spend the remainder of his life. The half a dozen camel-loads of gold and jewels that the Mughal royals had brought with them was beyond anything that had previously been seen in Arakan.[21]

After eight months and numerous excuses however, Sanda Thudhamma's promise of ships had not materialised. Finally, the latter demanded the hand of Shuja's daughter in marriage, which the prince refused. Sanda Thudhamma responded by ordering the Mughals to leave within three days. Unable to move and being refused provisions at the bazars, Shuja resolved to attempt to overthrow the king. The prince had two hundred soldiers with him, as well as the support of the local Muslims, giving him a good chance of success. However, Sanda Thudhamma was forewarned of the coup attempt. Shuja was therefore forced to set fire to the city in the hopes of cutting his way out in the confusion. Much of his entourage was captured, and though he himself initially escaped into the jungle, he was later captured and executed.[22]

Shuja's wealth was taken and melted down by Sanda Thudhamma, who took the Mughal princesses into his harem. He married the eldest, an event that was subsequently celebrated in song and poetry. The following year however, suspicious of another coup, Sanda Thudhamma had Shuja's sons decapitated and his daughters (including the pregnant eldest) starved to death. Aurangzeb, angered by the deaths, ordered a campaign against the kingdom. After an intensive siege, the Mughals captured Chittagong and thousands of Arakanese were taken into slavery. Arakan was unable to return to its previous dominance and Sanda Thudhamma's eventual death was followed by a century of chaos.[23]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Shah Shuja (Mughal prince) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shah Shuja. |

References

- Abdul Karim. "Shah Shuja". Banglapedia. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- Stanley Lane-Pool, 1971, Aurangzeb, vol.1.

- Mukherjee, Soma (2001). Royal Mughal Ladies and Their Contributions. Gyan Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-8-121-20760-7.

- Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (13 April 2015). Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 285. ISBN 978-0-300-21110-8.

- Jain, Simi (2003). Encyclopaedia of Indian Women Through the Ages: The middle ages. Gyan Publishing House. p. 73. ISBN 978-8-178-35173-5.

- Kr Singh, Nagendra (2001). Encyclopaedia of women biography: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Volume 3. A.P.H. Pub. Corp. p. 51. ISBN 978-8-176-48264-6.

- Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society - Volumes 1-2. Pakistan Historical Society. 1953. p. 338.

- Abdul Karim (1993). History of Bengal: The Reigns of Shah Jahan and Aurangzib. Institute of Bangladesh Studies, University of Rajshahi, 1995 - Bengal (India). p. 363.

- Singh, Nagendra Kr (2001). Encyclopaedia of Muslim Biography: Muh-R. A.P.H. Pub. Corp. p. 402. ISBN 978-8-176-48234-9.

- Kānunago, Sunīti Bhūshaṇa (1988). A History of Chittagong: From ancient times down to 1761. Dipankar Qanungo. p. 304.

- Phayre, Arthur P. (17 June 2013). History of Burma: From the Earliest Time to the End of the First War with British India. Routledge. pp. 178–9. ISBN 978-1-136-39841-4.

- Journal of the Asiatic Society of Pakistan. Asiatic Society of Pakistan. 1967. p. 251.

- Rap, Edward James; Heg, Sir Wolseley; Burn, Sir Richard (1928). The Cambridge History of India, Volume 3. CUP Archive. p. 481.

- Hangloo, Rattan Lal (1 January 2000). The State in Medieval Kashmir. Manohar. p. 130.

- Khan, Inayat; Begley, Wayne Edison (1990). The Shah Jahan name of 'Inayat Khan: an abridged history of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, compiled by his royal librarian: the nineteenth-century manuscript translation of A.R. Fuller (British Library, add. 30,777). Oxford University Press. p. 327.

- Ayesha Begum. "Bara Katra". Banglapedia. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- Abdul Karim. "Mir Jumla". Banglapedia. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Battle of Khajwa Archived 29 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Sunīti Bhūshaṇa Kānunago, A History of Chittagong: From ancient times down to 1761 (1988), p. 305

- Niccolao Manucci, Storia do Mogor or History of Mughal India, translator William Irvine

- Edward James Rapson, Sir Wolseley Haig, Sir Richard Burn, The Cambridge History of India Vol. IV: The Mughal Period (1937), p. 480

- Rapson et al. (1937, p. 481)

- Rapson et al. (1937, p. 481-2)

- Mehta (1986, p. 374)

- Jl Mehta, Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India (1986), p. 418

- Mehta (1986, p. 374)

- Kobita Sarker, Shah Jahan and his paradise on earth: the story of Shah Jahan's creations in Agra and Shahjahanabad in the golden days of the Mughals (2007), p. 187

- Soma Mukherjee, Royal Mughal Ladies and Their Contributions (2001), p. 128

- Mehta (1986, p. 418)

- Mukherjee (2001, p. 128)

- Subhash Parihar, Some Aspects of Indo-Islamic Architecture (1999), p. 149

- Frank W. Thackeray, John E. Findling, Events That Formed the Modern World (2012), p. 254

- Shujauddin, Mohammad; Shujauddin, Razia (1967). The Life and Times of Noor Jahan. Caravan Book House. p. 1.

- Sarker (2007, p. 187)

- Ahmad, Moin-ud-din (1924). The Taj and Its Environments: With 8 Illus. from Photos., 1 Map, and 4 Plans. R. G. Bansal. p. 101.

- Thackeray, Findling (2012, p. 254)

Further reading

- JN Sarkar (ed), History of Bengal, vol II, Dhaka, 1948

- JN Sarkar, History of Aurangzib, vol II, New Delhi, 1972–74

- A Karim, History of Bengal, Mughal Period, vol II, Rajshahi, 1995