German destroyer Z25

Z25 was one of fifteen Type 1936A destroyers built for the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) during World War II. Completed in 1940, the ship spent most of the war in Norwegian waters, escorting German ships and laying minefields, despite venturing to France in early 1942 to successfully escort two battleships and a heavy cruiser home through the English Channel (the Channel Dash). She was very active in attacking the Arctic convoys ferrying war materials to the Soviet Union in 1941–1942, but only helped to sink one Allied ship herself.

Sister ship Z29, 1945 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Z25 |

| Ordered: | 23 April 1938 |

| Builder: | AG Weser (Deschimag), Bremen |

| Yard number: | W959 |

| Laid down: | 15 February 1939 |

| Launched: | 16 March 1940 |

| Completed: | 30 November 1940 |

| Captured: | 6 May 1945 |

| Name: | Hoche |

| Namesake: | General Lazare Hoche |

| Acquired: | 2 February 1946 |

| Decommissioned: | 20 August 1956 |

| In service: | August 1946 |

| Renamed: | Q102, 2 January 1958 |

| Stricken: | 2 January 1958 |

| Fate: | Scrapped, 1961 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type: | Type 1936A destroyer |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 127 m (416 ft 8 in) (o/a) |

| Beam: | 12 m (39 ft 4 in) |

| Draft: | 4.43 m (14 ft 6 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 2 × shafts; 2 × geared steam turbine sets |

| Speed: | 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph) |

| Range: | 2,500 nmi (4,600 km; 2,900 mi) at 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) |

| Complement: | 332 |

| Armament: |

|

| Service record | |

| Commanders: | Carl-Heinz Birnbacher |

Engine problems in 1943 severely restricted her activities and she was transferred to the Baltic in early 1944 after repairs were completed. Z25 spent most of the rest of the war escorting ships as the Germans evacuated East Prussia and bombarding Soviet forces. The ship was captured by the Allies in May 1945 and spent the rest of the year under British control as the Allies decided how to dispose of the captured German ships.

She was ultimately allotted to France in early 1946 and renamed Hoche. She became operational later that year and cruised to French colonies in Africa during 1947. The ship was placed in reserve in early 1949 before beginning a reconstruction from 1950–1953 that converted her into a fast destroyer escort. Worn out by 1956, Hoche was deemed too expensive to repair and decommissioned later that year. The ship was condemned in 1958 and scrapped in 1961.

Design and description

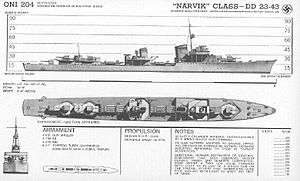

The Type 1936A destroyers were slightly larger than the preceding Type 1936 class and had a heavier armament. They had an overall length of 127 meters (416 ft 8 in) and were 121.90 meters (399 ft 11 in) long at the waterline. The ships had a beam of 12 meters (39 ft 4 in), and a maximum draft of 4.43 meters (14 ft 6 in). They displaced 2,543 long tons (2,584 t) at standard load and 3,543 long tons (3,600 t) at deep load. The two Wagner geared steam turbine sets, each driving one propeller shaft, were designed to produce 70,000 PS (51,000 kW; 69,000 shp) using steam provided by six Wagner water-tube boilers for a designed speed of 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph). Z25 carried a maximum of 791 metric tons (779 long tons) of fuel oil which gave a range of 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km; 2,900 mi) at 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). Her crew consisted of 11 officers and 321 sailors.[1]

The ship carried four 15-centimeter (5.9 in) TbtsK C/36 guns in single mounts with gun shields, one forward of the superstructure and three aft. They were designated No. 1 to 4 from front to rear. Her anti-aircraft armament consisted of four 3.7-centimeter (1.5 in) C/30 guns in two twin mounts abreast the rear funnel and five 2-centimeter (0.8 in) C/30 guns in single mounts. Z25 carried eight above-water 53.3-centimeter (21 in) torpedo tubes in two power-operated mounts.[1] Two reloads were provided for each mount. She had four depth charge launchers and mine rails could be fitted on the rear deck that had a maximum capacity of 60 mines. 'GHG' (Gruppenhorchgerät) passive hydrophones were fitted to detect submarines and an S-Gerät sonar was also probably fitted. The ship was equipped with a FuMO 24/25 radar set above the bridge.[1][2]

Modifications

Z25's single forward 15 cm gun was exchanged for a 15 cm LC/38 twin-gun turret during her mid-1942 refit. This exacerbated the Type 36A's tendency to take water over the bow and reduced their speed to 32.8 knots (60.7 km/h; 37.7 mph).[3] No. 3 gun was later removed to make room for additional AA guns under the 1944 Barbara program. By the end of the war, her anti-aircraft suite consisted of ten 3.7 cm guns in single and twin mounts and sixteen 2 cm weapons in twin and quadruple mounts. Most, if not all, of the 3.7 cm guns were to be the faster-firing Flak M42 model.[4][Note 1]

A FuMO 21 radar replaced the FuMO 24/25 in 1944 and FuMB 1 Metox, FuMB 3 Bali, and FuMB 6 Palau radar detectors were added that same year. A FuMO 63 Hohentwiel radar was installed in 1944–1945 in lieu of the aft searchlight.[7]

Service history

Z25 was ordered from AG Weser (Deschimag) on 23 April 1938. The ship was laid down at Deschimag's Bremen shipyard as yard number W959 on 15 February 1939, launched on 16 March 1940, and commissioned on 30 November. She finished working up on 26 June 1941 and sailed for Norway, but ran aground off Haugesund, damaging both propellers, and had to return to Bremen for repairs. Z25 was assigned to escort the Baltic Fleet, a temporary formation built around the battleship Tirpitz, as it sortied into the Sea of Åland on 23–29 September to forestall any attempt by the Soviet Red Banner Baltic Fleet to breakout from the Gulf of Finland.[8]

Two months later Z25 accompanied her sister ships, Z23 and Z27 from Germany to Norway and arrived in Tromsø on 6 December where she was assigned to the 8. Zerstörerflottile (8th Destroyer Flotilla). After arriving in Kirkenes, the ship replaced Z26 as the flagship of Kapitän zur See (Captain) Hans Erdmenger, commander of the flotilla, as the latter destroyer had engine problems and had to return to Germany for repairs. She led her sisters Z23, Z24 and Z27 out into the Barents Sea on 16 December 1941, searching for Allied ships off the coast of the Kola Peninsula. The following day, Z25's radar spotted two ships in heavy fog at a range of 37.5 kilometers (23.3 mi). The Germans thought that they were Soviet destroyers, but they were actually two British minesweepers, Hazard and Speedy, sailing to rendezvous with Convoy QP 6. The Germans intercepted them, but the heavy fog and icing precluded accurate gunfire. The British ships were able to escape despite four hits on Speedy and the heavy expenditure of ammunition; Z25 and Z27 attempted to fire 11 torpedoes between them, but were only able to launch one each. On 13 January 1942, Z25 escorted Z23 and Z24 as they laid a minefield in the western channel of the White Sea.[9]

On the 29th, Z25 sailed from Kirkenes to rendezvous with the destroyer Z7 Hermann Schoemann at Vlissingen, the Netherlands, before continuing onward together to Brest, France, where they arrived on 7 February as part of the preparations for the Channel Dash. The German ships departed Brest on 11 February, totally surprising the British. During the sporadic attacks by the British, Z25 is not known to have engaged any British ships or aircraft, not was she damaged in any way. Shortly afterwards, the ship joined four other destroyers in escorting the heavy cruisers Prinz Eugen and Admiral Scheer to Trondheim. Heavy weather forced three of the destroyers to return to port before reaching their destination and Prinz Eugen was badly damaged by a British submarine after their separation.[10]

Anti-convoy operations

On 6 March, Tirpitz, escorted by Z25 and three other destroyers, sortied to attack the returning Convoy QP 8 and the Russia-bound PQ 12 as part of Operation Sportpalast (Sports Palace). The following morning, Admiral Otto Ciliax, commanding the operation, ordered the destroyers to search independently for Allied ships and they stumbled across the 2,815-gross register ton (GRT) Soviet freighter SS Ijora, a straggler from QP 8, later that afternoon and sank her. Tirpitz rejoined them shortly afterwards and Ciliax ordered the destroyers back to Trondheim on the 8th after failing to refuel them the previous night due to heavy seas and icing.[11]

On 28 March, Z26 and her sisters Z24 and Z25 departed the Varangerfjord in an attempt to intercept Convoy PQ 13. Later that night they rescued 61 survivors of the sunken freighter SS Empire Ranger then sank the straggling 4,687 GRT freighter SS Bateau. They rescued 7 survivors before resuming the search for the convoy. The light cruiser HMS Trinidad, escorted by the destroyer HMS Fury, spotted the German ships with her radar at 08:49 on the 29th and was spotted herself around that same time. Both sides opened fire at the point-blank range of 3,200 yards (2,900 m) in a snowstorm. Trinidad engaged the leading German destroyer, Z26, badly damaging her, and then switched to Z25 without making any hits. Between them the destroyers fired 19 torpedoes at the cruiser, all of which missed after Trinidad turned away, and hit her twice with their 15 cm guns, inflicting only minor damage. The British ships maneuvered to avoid torpedoes, which forced them to disengage, and Z26 accidentally became separated from her sisters.[12]

After Fury turned away to render assistance to the cruiser, the destroyer HMS Eclipse took up the pursuit, crippling Z26 by 10:20. Eclipse was maneuvering to give the German destroyer the coup de grâce with a torpedo when the snowstorm ended and visibility increased, revealing Z24 and Z25 approaching. They promptly opened fire at Eclipse, hitting her twice and wounding nine men, before she could find cover in a squall at 10:35. The German ships did not purse Eclipse, preferring to heave to and take off 88 survivors from Z26.[13]

The two destroyers, now reinforced by Z7 Hermann Schoemann and assigned to Zerstörergruppe Arktis (Destroyer Group Arctic), commanded by Kapitän zur See Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs, searched unsuccessfully for Convoys PQ 14 and QP 10 on 11 April.[14] On 30 April German submarine U-456 torpedoed and crippled the light cruiser Edinburgh, part of the close escort for Convoy QP 11. Later that day, the trio of destroyers were ordered to intercept her. The following afternoon they encountered the main body of the convoy and attacked in limited visibility. Over the next four hours, they made five attempts to close with the convoy, but the four escorting British destroyers were able to keep themselves between the Germans and the convoy. After being rebuffed, Schulze-Hinrichs decided to break off the attack and search for his original objective. The German ships were only able to sink the 2,847 GRT freighter, SS Tsiolkovsky, with torpedoes from Z24 and Z25, and badly damage the escort destroyer Amazon with gunfire. The British ships did not make any hits on the German destroyers.[15]

Later that day, Edinburgh's original escort of two destroyers was augmented by four British minesweepers and a small Russian tugboat. The cruiser was steaming under her own power at a speed of about 3 knots (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph) by the morning of 2 May with steering provided by the tugboat. She was spotted by the Germans and Z7 Hermann Schoemann exchanged fire with the minesweeper Harrier at about 06:27. Edinburgh then cast off her tow and increased speed to her maximum of about 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph), steering in a circle. While Z7 Hermann Schoemann maneuvered to obtain a good position from which to fire torpedoes, the cruiser opened fire at 06:36, almost immediately severing the main steam line, which disabled the engines. Z25 initially engaged the destroyer Forester, hitting her three times at about 06:50, which disabled two guns and knocked out her power with a hit in her forward boiler room. Her sister Foresight passed in front of Forester a few minutes later to draw the attention of Z24 and Z25, which succeeded all too well as she was hit four times by 07:24, disabling the engines and leaving her with only a single gun operable. In the meantime, the cruiser had been hit once more by a torpedo at 07:02, although it only knocked out her engines and gave her a list to port. Rather than sink any of the three disabled British ships or the lightly armed minesweepers, Z24 and Z25 concentrated on rescuing the crew of the drifting Z7 Hermann Schoemann despite occasional British shells. The former made multiple attempts to come alongside to take off about 210 survivors while the latter laid a smoke screen. Z7 Hermann Schoemann was then scuttled using her own depth charges. Z24 was unscathed during the battle, but Z25 was hit in the radio room, killing four and wounding seven. In Operation Zauberflote (Magic Flute), Z25, the destroyer Z5 Paul Jacobi, and two torpedo boats escorted the badly damaged Prinz Eugen from Trondheim to Kiel from 16–18 May. Shortly after her arrival, the destroyer began a lengthy refit that lasted until November.[16]

On 11 November, the ship escorted the light cruiser Nürnberg from Swinemünde to Trondheim. In February 1943, she sailed to Germany in preparation for continuing onward to France, but engine problems caused that plan to be cancelled on 5 March. Z25 returned to Norwegian waters on April 22, but continuing engine problems kept her mostly inactive before her return to Germany for an overhaul in August. While running sea trials in Danzig Bay, the shock wave from a nearby mine explosion disabled her port turbine and required further repairs.[17]

Baltic operations

Now assigned to the 6. Zerstörerflotille, Z25 and the other three destroyers of the flotilla were transferred to the Gulf of Finland to support minelaying operations there, Z25 arriving at Reval, Estonia, on 13 February 1944. The flotilla was initially tasked to escort convoys between Libau, Latvia, and Reval, but laid its first minefield in Narva Bay on 12 March while bombarding Soviet positions on the eastern shore of the bay. They were primarily tasked as minelayers through July.[18] In preparation for Operation Tanne West, the occupation of the Åland Islands in case of Finnish surrender, the flotilla escorted the heavy cruiser Lützow to the island of Utö on 28 June, but the operation was canceled and the ships returned to port.[19]

On 30 July and 1 August Z25 and three other destroyers of the flotilla sailed into the Gulf of Riga to bombard Soviet positions inland. On 5 August, they escorted Prinz Eugen as she engaged targets on the island of Oesel, Estonia, and in Latvia on 19–20 August. Between 15 and 20 September, the ship helped to evacuate 23,172 people from Reval in the face of the advancing Soviets. On 21 August, the ship, together with the destroyer Z28, ferried 370 people from Baltischport, Estonia, to Libau. The following day, she escorted ships loaded with evacuees from the Sea of Åland to Gotenhafen, Germany. On 10 October, Z25 ferried 200 reinforcements to Memel and evacuated 200 female naval auxiliaries the next day. Upon her return, the ship bombarded targets near Memel. She was then slightly damaged by a presumed near-miss from a torpedo and the vibrations from her own guns caused an oil leak on one of her fuel tanks.[20]

On 4 November, Z25 was transferred to the 8. Zerstörerflotille and supported Lützow and Prinz Eugen as they engaged Soviet positions in Sworbe, on the Estonian island of Saaremaa, between 19 and 24 November. She was refitted in December and then bombarded Soviet troops east and south of Königsberg, together with Prinz Eugen and two torpedo boats on 29–30 January 1945 and again on 2–5 February to allow cut-off German Army units to break through into friendly territory. The ship then escorted many refugee ships carrying evacuees between Gotenhafen and Sassnitz before bombarding Soviet positions near the former city on the 20th. A month later, Z25 and Z5 Paul Jacobi escorted the ocean liner Potsdam, the troopship SS Goya and the target ship Canonier as they ferried 22,000 refugees to Copenhagen, Denmark, on 26 March. The ship continued to escort refugee ships between Hela and friendly territory through April and into May. On the 5th, she helped to convey 45,000 refugees to Copenhagen and returned to ferry 20,000 more to Glücksburg, Germany, on the 9th. The following day, Z25 was decommissioned.[21]

French service

After the war Z25 sailed to Wilhelmshaven and was overhauled to keep her seaworthy while the Allies decided how to divide the surviving ships of the Kriegsmarine amongst themselves as war reparations. The ship was allotted to Great Britain in late 1945 and arrived in Rosyth, Scotland, on 6 January 1946. Following protests by France over her exclusion, the British transferred four of the destroyers that they had been allotted and Z25 arrived in Cherbourg on 2 February. Two days later, she was commissioned into the French Navy with the name of Hoche, after General Lazare Hoche. The ship was assigned to the 1st Division of Large Destroyers (contre-torpilleurs) and entered service in September when she conducted training with the light carrier Arromanches. In March–June 1947, she formed part of the escort for the battleship Richelieu as the President of France, Vincent Auriol, visited West and North Africa. Hoche visited Portsmouth, England, in December 1948 before she was reduced to reserve on 1 January 1949. From 1950 to 1953, the ship was rebuilt into a escorteur rapide (fast escort destroyer) with new weapons and electronics and was based in Toulon for anti-submarine trials. A major refit was necessary by 1956, but it was not economical and she was placed in reserve on 20 August before being decommissioned on 1 September. Hoche was condemned and redesignated Q102 on 2 January 1958; she was listed for sale on 30 June and scrapped in 1961.[22]

Notes

Citations

- Gröner, pp. 203–04

- Whitley, pp. 68, 71–72

- Gröner, p. 203; Koop & Schmolke, p. 105

- Whitley, pp. 73–74

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 34

- Gröner, p. 203

- Gröner, p. 204; Koop & Schmolke, p. 40

- Koop & Schmolke, pp. 24, 105; Rohwer, p. 103

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 105; Rohwer, pp. 127, 135; Whitley, pp. 131–32

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 105; Rohwer, p. 143; Whitley, pp. 118–20, 132–33

- Whitley, pp. 133–34

- Admiralty Historical Section 2007, pp. 27–29; Whitley, pp. 135–36

- Admiralty Historical Section 2007, pp. 29–30; Whitley, p. 136

- Rohwer, p. 158; Whitley, pp. 136–37

- Admiralty Historical Section 2007, pp. 37–39; Rohwer, p. 162; Whitley, pp. 136–38

- Admiralty Historical Section 2007, pp. 40–42; Koop & Schmolke, p. 105; Whitley, pp. 138–40

- Koop & Schmolke, pp. 105–06; Whitley, pp. 145–46

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 106; Whitley, pp. 173–75

- Rohwer, p. 339

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 106

- Koop & Schmolke, pp. 106–07; Rohwer, p. 414; Whitley, p. 180

- Koop & Schmolke, p. 107; Whitley, pp. 196–97

References

- Admiralty Historical Section (2007). The Royal Navy and the Arctic Convoys. Naval Staff Histories. Abingdon, UK: Whitehall History in association with Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5284-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Volume 1: Major Surface Warships. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-790-9.

- Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2003). German Destroyers of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-307-1.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Whitley, M. J. (1991). German Destroyers of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-302-8.