German Army (1935–1945)

The German Army (German: Heer, German: [heːɐ̯] (![]()

| German Army | |

|---|---|

| Heer | |

Helmet decal used by the German Army | |

| Active | 1935–1945 |

| Disbanded | 1946 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Ground forces |

| Size | Total served: 13,600,000[1] |

| Part of | Wehrmacht |

| Headquarters | Maybach I, Wünsdorf |

| Equipment | List of army equipment |

| Engagements | Spanish Civil War World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Supreme Commander-in-chief | Adolf Hitler |

| Commander-in-chief of the Army | See list |

| Chief of the General Staff | See list |

| Insignia | |

| Ranks and insignia | Ranks and insignia of the Army |

| Unit flag |  |

Only 17 months after Adolf Hitler announced the German rearmament program in 1935, the army reached its projected goal of 36 divisions. During the autumn of 1937, two more corps were formed. In 1938 four additional corps were formed with the inclusion of the five divisions of the Austrian Army after the Anschluss in March.[3] During the period of its expansion under Hitler, the German Army continued to develop concepts pioneered during World War I, combining ground and air assets into combined arms forces. Coupled with operational and tactical methods such as encirclements and "battle of annihilation", the German military managed quick victories in the two initial years of World War II, a new style of warfare described as Blitzkrieg (lightning war) for its speed and destructive power.[4]

The German Army fought a war of annihilation on the Eastern Front and was responsible for many war crimes alongside the Waffen and Allgemeine SS.

Structure

The Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) was Nazi Germany's Army High Command from 1936 to 1945. In theory, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) served as the military General Staff for the Reich's armed forces, coordinating the Wehrmacht (Heer, Kriegsmarine, and the Luftwaffe) operations. In practice, the OKW acted in a subordinate role to Hitler's personal military staff, translating his ideas into military plans and orders, and issuing them to the three services.[5] However, as World War II went on, the OKW found itself exercising an increasing amount of direct command authority over military units, particularly in the west. This meant that by 1942 the OKW was the de facto command of Western Theatre forces while the Army High Command (OKH) was the same on the Eastern Front.[6]

The Abwehr was the army intelligence organization from 1921 to 1944. The term Abwehr (German for "defense", here referring to counter-intelligence) had been created just after World War I as an ostensible concession to Allied demands that Germany's intelligence activities be for defensive purposes only. After 4 February 1938, the name Abwehr was changed to the Overseas Department/Office in Defence of the Armed Forces High Command (Amt Ausland/Abwehr im Oberkommando der Wehrmacht).

Germany used a system of military districts (German: Wehrkreis) in order to relieve field commanders of as much administrative work as possible and to provide a regular flow of trained recruits and supplies to the field forces. The method OKW adopted was to separate the Field Army (OKH) from the Home Command (Heimatkriegsgebiet) and to entrust the responsibilities of training, conscription, supply, and equipment to Home Command.

Organization of field forces

The German Army was mainly structured in Army groups (Heeresgruppen) consisting of several armies that were relocated, restructured or renamed in the course of the war. Forces of allied states, as well as units made up of non-Germans, were also assigned to German units.

For Operation Barbarossa in 1941, the Army forces were assigned to three strategic campaign groupings:

- Army Group North with Leningrad as its campaign objective

- Army Group Centre with Smolensk as its campaign objective

- Army Group South with Kiev as its campaign objective

Below the army group level forces included field armies – panzer groups, which later became army level formations themselves, corps, and divisions. The army used the German term Kampfgruppe, which equates to battle group in English. These provisional combat groupings ranged from corps size, such as Army Detachment Kempf, to commands composed of companies or even platoons. They were named for their commanding officers.

Select arms of service

- Panzerjäger (Anti-tank troops)

- Panzergrenadier (Armoured infantry troops)

- Panzerwaffe (Armoured troops)

- Army propaganda troops

- Experimental command Kummersdorf

- Foreign Armies East

- Feldgendarmerie (Military police)

- Gebirgsjäger (Mountain troops)

- Geheime Feldpolizei (Secret Field Police)

- Prussian Military Academy

- Kriegsschule (War college)

Doctrine and tactics

The German operational doctrine emphasized sweeping pincer and lateral movements meant to destroy the enemy forces as quickly as possible. This approach, referred to as Blitzkrieg, was an operational doctrine instrumental in the success of the offensives in Poland and France. Blitzkrieg has been considered by many historians as having its roots in precepts developed by Fuller, Liddel-Hart and von Seeckt, and even having ancient prototypes practiced by Alexander, Genghis Khan and Napoleon.[7][8] Recent studies of the Battle of France also suggest that the actions of either Rommel or Guderian or both of them (both had contributed to the theoretical development and early practices of what later became Blitzkrieg prior to World War II),[9][10] ignoring orders of superiors who had never foreseen such spectacular successes and thus prepared much more prudent plans, were conflated into a purposeful doctrine and created the first archetype of Blitzkrieg, which then gained a fearsome reputation that dominated the Allied leaders' minds.[11][12][13] Thus 'Blitzkrieg' was recognised after the fact, and while it became adopted by the Wehrmacht, it never became the official doctrine nor got used to its full potential because only a small part of the Wehrmacht was trained for it and key leaders at the highest levels either focused on only certain aspects or even did not understand what it was.[14][15][16]

Max Visser argues that the German army focused on achieving high combat performance rather than high organisational efficiency (like the US army). It emphasised adaptability, flexibility and decentralised decision making. Officers and NCOs were selected based on character and trained towards decisive combat leadership and rewarded good combat performance. Visser argues this allowed the German army to achieve superior combat performance compared to a more traditional organisational doctrine like the American one; while this would be ultimately offset by the Allies' superior numerical and material advantage, Visser argues that this allowed the German army to resist far longer than if it had not adopted this method of organisation and doctrine.[17] Peter Turchin reports a study by American colonel Trevor Dupuy that found that German combat efficiency was higher than both the British and American armies - if a combat efficiency of 1 was assigned to the British, then the Americans had a combat efficiency of 1.1 and the Germans of 1.45. This would mean British forces would need to commit 45% more troops (or arm existing troops more heavily to the same proportion) to have a even chance of winning the battle, while the Americans would need to commit 30% more to have an even chance.[18]

Tactics

The military strength of the German Army was managed through mission-based tactics (Auftragstaktik) (rather than detailed order-based tactics), and an almost proverbial discipline. Once an operation began, whether offensive or defensive, speed in response to changing circumstances was considered more important than careful planning and coordination of new plans.

In public opinion, the German military was and is sometimes seen as a high-tech army, since new technologies that were introduced before and during World War II influenced its development of tactical doctrine. These technologies were featured by Nazi propaganda, but were often only available in small numbers or late in the war, as overall supplies of raw materials and armaments became low. For example, lacking sufficient motor vehicles to equip more than a small portion of their army, the Germans chose to concentrate the available vehicles in a small number of divisions which were to be fully motorized. The other divisions continued to rely on horses for towing artillery, other heavy equipment and supply-wagons, and the men marched on foot or rode bicycles. At the height of motorization only 20 per cent of all units were fully motorized. The small German contingent fighting in North Africa was fully motorized (relying on horses in the desert was near to impossible because of the need to carry large quantities of water and fodder), but the much larger force invading the Soviet Union in June 1941 numbered only some 150,000 trucks and some 625,000 horses (water was abundant and for many months of the year horses could forage – thus reducing the burden on the supply chain). However, the production of new motor vehicles by Germany, even with the exploitation of the industries of occupied countries, could not keep up with the heavy loss of motor vehicles during the winter of 1941–1942. From June 1941 to the end of February 1942 German forces in the Soviet Union lost some 75,000 trucks to mechanical wear and tear and combat damage – approximately half the number they had at the beginning of the campaign. Most of these were lost during the retreat in the face of the Soviet counteroffensive from December 1941 to February 1942. Another substantial loss was incurred during the defeat of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad in the winter of 1942–1943. These losses in men and materiel led to motorized troops making up no more than 10% of total Heer forces at some points of the war.

In offensive operations the infantry formations were used to attack more or less simultaneously across a large portion of the front so as to pin the enemy forces ahead of them and draw attention to themselves, while the mobile formations were concentrated to attack only narrow sectors of the front, breaking through to the enemy rear and surrounding him. Some infantry formations followed in the path of the mobile formations, mopping-up, widening the corridor manufactured by the breakthrough attack and solidifying the ring surrounding the enemy formations left behind, and then gradually destroying them in concentric attacks. One of the most significant problems bedeviling German offensives and initially alarming senior commanders was the gap created between the fast moving "fast formations" and the following infantry, as the infantry were considered a prerequisite for protecting the "fast formations" flanks and rear and enabling supply columns carrying fuel, petrol and ammunition to reach them.

In defensive operations the infantry formations were deployed across the front to hold the main defence line and the mobile formations were concentrated in a small number of locations from where they launched focused counterattacks against enemy forces who had broken through the infantry defence belt. In autumn 1942, at El Alamein, a lack of fuel compelled the German commander, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, to scatter his armoured units across the front in battalion-sized concentrations to reduce travel distances to each sector rather than hold them concentrated in one location. In 1944 Rommel argued that in the face of overwhelming Anglo-American air power, the tactic of employing the concentrated "fast formations" was no longer possible because they could no longer move quickly enough to reach the threatened locations because of the expected interdiction of all routes by Allied fighter-bombers. He therefore suggested scattering these units across the front just behind the infantry. His commanders and peers, who were less experienced in the effect of Allied air power, disagreed vehemently with his suggestion, arguing that this would violate the prime principle of concentration of force.

Campaigns

The infantry remained foot soldiers throughout the war; artillery also remained primarily horse-drawn. The motorized formations received much attention in the world press in the opening years of the war, and were cited as the main reason for the success of the German invasions of Poland (September 1939), Norway and Denmark (April 1940), Belgium, France and Netherlands (May 1940), Yugoslavia (April 1941) and the initial stages of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union (June 1941). However, their motorized and tank formations accounted for only 20% of the Heer's capacity at their peak strength. The army's lack of trucks (and of petroleum to run them) severely limited infantry movement, especially during and after the Normandy invasion when Allied air-power devastated the French rail network north of the Loire. Panzer movements also depended on the rail, since driving a tank long distances wore out its tracks.[19]

Personnel

Equipment

It is a myth that the German Army in World War II was a mechanized juggernaut as a whole. In 1941, between 74 and 80 percent of their forces were not motorized, relying on railroad for rapid movement and on horse-drawn transport cross country. The percentage of motorization decreased thereafter.[20] In 1944 approximately 85 percent was not motorized.[21] The standard uniform used by the German Army consisted of a Feldgrau (field grey) tunic and trousers, worn with a Stahlhelm.

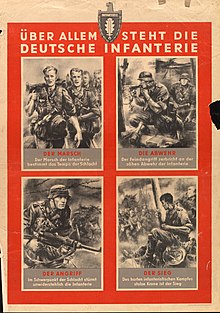

Propaganda

The German Army was promoted by Nazi propaganda.

War crimes

See also

Notes

- Though "Wehrmacht" is often erroneously used to refer only to the Army, it actually included the Kriegsmarine (Navy) and the Luftwaffe (Air Force).

References

- Overmans 2000, p. 257.

- Large 1996, p. 25.

- Haskew 2011, p. 28.

- Haskew 2011, pp. 61–62.

- Haskew 2011, pp. 40–41.

- Harrison 2002, p. 133.

- Rice Jr. 2005, pp. 9, 11.

- Paniccia 2014, p. ?.

- Grossman 1993, p. 3.

- Lonsdale 2007, p. ?.

- Showalter 2006, p. ?.

- Krause & Phillips 2006, p. 176.

- Stroud 2013, pp. 33-34.

- Caddick-Adams 2015, p. 17.

- Vigor 1983, p. 96.

- Zabecki 1999, p. 1175.

- Visser, Max. "Configurations of human resource practices and battlefield performance: A comparison of two armies." Human Resource Management Review 20, no. 4 (2010): 340-349.

- Turchin, P., 2007. War and peace and war: The rise and fall of empires. Penguin, pp.257-258

- Keegan 1982, pp. 156–157.

- Zeiler & DuBois 2012, pp. 171-172.

- Tucker 2009, p. 1885.

Bibliography

- Caddick-Adams, Peter (2015). Snow & Steel: The Battle of the Bulge, 1944-45. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199335145.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- CIA (24 August 1999). "Records Integration Title Book" (PDF). Retrieved 11 December 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grossman, David A. (1993). Maneuver Warfare in the Light Infantry-The Rommel Model (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrison, Gordon A. (2002). The Cross Channel Attack (Publication 7-4).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haskew, Michael (2011). The Wehrmacht: 1935–1945. Amber Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-907446-95-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keegan, John (1982). Six Armies in Normandy. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670647361.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krause, Michael D.; Phillips, R. Cody (2006). Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160725647.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Large, David Clay (1996). Germans to the Front: West German Rearmament in the Adenauer Era. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807845394.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lonsdale, David J. (Dec 10, 2007). Alexander the Great: Lessons in Strategy. Routledge. ISBN 9781134244829.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Overmans, Rüdiger (2000). Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg (in German). De Gruyter Oldenbourg. ISBN 3-486-56531-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paniccia, Arduino (Jan 14, 2014). Reshaping the Future: Handbook for a new Strategy. Mazzanti Libri - Me Publisher. ISBN 9788898109180.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rice Jr., Earle (2005). Blitzkrieg! Hitler's Lightning War. Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. ISBN 9781612286976.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shepherd, Ben (2016). Hitler's Soldiers: The German Army in the Third Reich. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300179033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Showalter, Dennis (Jan 3, 2006). Patton And Rommel: Men of War in the Twentieth Century. Penguin. ISBN 9781440684685.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stroud, Rick (2013). The Phantom Army of Alamein: The Men Who Hoodwinked Rommel. A&C Black. ISBN 9781408831281.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vigor, P.H. (1983). Soviet Blitzkrieg Theory. Springer. ISBN 9781349048144.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zabecki, David T. (1999). World War Two in Europe. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824070298.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zeiler, Thomas W.; DuBois, Daniel M. (2012). A Companion to World War II. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-32504-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heer (Wehrmacht). |

- "The Role of the German Army during the Holocaust: A Brief Summary.": Video on YouTube—lecture by Geoffrey P. Megargee, via the official channel of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.