Genetic purging

Genetic purging is the reduction of the frequency of a deleterious allele, caused by an increased efficiency of natural selection prompted by inbreeding.[1]

Purging occurs because many deleterious alleles only express all their harmful effect when homozygous, present in two copies. During inbreeding, as related individuals mate, they produce offspring that are more likely to be homozygous. Deleterious alleles appear more often, making individuals less fit genetically, i.e. they pass fewer copies of their genes to future generations. Put another way, natural selection purges the deleterious alleles.

Purging reduces both the overall number of recessive deleterious alleles and the decline of mean fitness caused by inbreeding (the inbreeding depression for fitness).

The term "purge" is sometimes used for selection against deleterious alleles in a general way. It would avoid ambiguity to use "purifying selection" in that general context, and to reserve purging to its more strict meaning defined above.

The mechanism

Deleterious alleles segregating in populations of diploid organisms have a remarkable trend to be, at least, partially recessive. This means that, when they occur in homozygosis (double copies), they reduce fitness by more than twice than when they occur in heterozygosis (single copy). In other words, part of their potential deleterious effect is hidden in heterozygosis but expressed in homozygosis, so that selection is more efficient against them when they occur in homozygosis. Since inbreeding increases the probability of being homozygous, it increases the fraction of the potential deleterious effect that is expressed and, therefore, exposed to selection. This causes some increase in the selective pressure against (partially) recessive deleterious alleles, which is known as purging. Of course, it also causes some reduction in fitness, which is known as inbreeding depression.

Purging can reduce the average frequency of deleterious alleles across the genome below the value expected in a non-inbred population.[2] Although this reduction usually does not compensate for all the negative effects of inbreeding,[3] it has several beneficial consequences for fitness. A consequence is the reduction of the so-called inbreeding load. This means that, after purging, further inbreeding is expected to be less harmful. But the most immediate consequence is the reduction of the actual inbreeding depression of fitness: due to purging, mean fitness declines less than would be expected just from inbreeding and, after some initial decline, it can even rebound up to almost its value before inbreeding.[4]

The joint effect of inbreeding and purging on fitness

Accounting for purging when predicting inbreeding depression is important in evolutionary genetics, because the fitness decline caused by inbreeding can be determinant in the evolution of diploidy, sexual reproduction and other main biological features. It is also important in animal breeding and, of course, in conservation genetics, because inbreeding depression may be a relevant factor determining the extinction risk of endangered populations, and because conservation programs can allow some breeding handling in order to control inbreeding.[5]

In brief, Due to purging, inbreeding depression is not proportional to the standard measure of inbreeding (Wright's inbreeding coefficient F), since this measure only applies to neutral alleles. Instead, fitness decline is proportional to "purged inbreeding" g, which gives the probability of being homozygous for deleterious alleles due to inbreeding, taking into account how they are being purged.

Purging reduces inbreeding depression in two ways: first, it slows its progress; second, it reduces the overall inbreeding depression expected in the long term. The slower the progress of inbreeding, the more efficient is purging.

A more detailed explanation

In the absence of natural selection, mean fitness would be expected to decline exponentially as inbreeding increases, where inbreeding is measured using Wright's inbreeding coefficient F[6] (the reason why decline is exponential on F instead of linear is just that fitness is usually considered a multiplicative trait). The rate at which fitness declines as F increases (the inbreeding depression rate δ) depends on the frequencies and deleterious effects of the alleles present in the population before inbreeding.

The above coefficient F is the standard measure of inbreeding, and gives the probability that, at any given neutral locus, an individual has inherited two copies of a same gene of a common ancestor (i.e. the probability of being homozygous "by descent"). In simple conditions, F can be easily computed in terms of population size or of genealogical information. F is often denoted using lowercase (f), but should not be confused with the coancestry coefficient.

However, the above prediction for the fitness decline rarely applies, since it was derived assuming no selection, and fitness is precisely the target trait of natural selection. Thus, Wright's inbreeding coefficient F for neutral loci does not apply to deleterious alleles, unless inbreeding increases so fast that the change in gene frequency is governed just by random sampling (i.e., by genetic drift).

Therefore, the decline of fitness should be predicted using, instead of the standard inbreeding coefficient F, a "purged inbreeding coefficient" (g) that gives the probability of being homozygous by descent for (partially) recessive deleterious alleles, taking into account how their frequency is reduced by purging.[4] Due to purging, fitness declines at the same rate δ than in the absence of selection, but as a function of g instead of F.

This purged inbreeding coefficient g can also be computed, to a good approximation, using simple expressions in terms of the population size or of the genealogy of individuals (see BOX 1). However this requires some information on the magnitude of the deleterious effects that are hidden in the heterozygous condition but become expressed in homozygosis. The larger this magnitude, denoted purging coefficient d, the more efficient is purging.

An interesting property of purging is that, during inbreeding, while F increases approaching a final value F = 1, g can approach a much smaller final value. Hence, it is not just that purging slows the fitness decline, but also that it reduces the overall fitness loss produced by inbreeding in the long term. This is illustrated in BOX 2 for the extreme case of inbreeding depression caused by recessive lethals, which are alleles that cause death before reproduction but only when they occur in homozygosis. Purging is less effective against mildly deleterious alleles than against lethal ones but, in general, the slower is the increase of inbreeding F, the smaller becomes the final value of the purged inbreeding coefficient g and, therefore, the final reduction in fitness. This implies that, if inbreeding progresses slowly enough, no relevant inbreeding depression is expected in the long term. This results in the fitness of a small population, that has been a small population for a long time, can be the same as a large population with more genetic diversity. In conservation genetics, it would be very useful to ascertain the maximum rate of increase of inbreeding that allows for such efficient purging.

Examples

Predictive equations when inbreeding is due to small population size

Consider a large non-inbred population with mean fitness W. Then, the size of the population reduces to a new smaller value N (in fact, the effective population size should be used here), leading to a progressive increase of inbreeding.

Then inbreeding depression occurs at a rate δ, due to (partially) recessive deleterious alleles that were present at low frequencies at different loci. This means that, in the absence of selection, the expected value for mean fitness after t generations of inbreeding, would be:

where is the population mean for Wright's inbreeding coefficient after t generations of inbreeding.[6]

However, since selection operates upon fitness, mean fitness should be predicted taking into account both inbreeding and purging, as

In the above equation, is the average "purged inbreeding coefficient" after t generations of inbreeding.[4] It depends upon the "purging coefficient" d, which represents the deleterious effects that are hidden in heterozygosis but exposed in homozygosis.

The average "purged inbreeding coefficient" can be approximated using the recurrent expression

There are also predictive equations to be used with genealogical information.

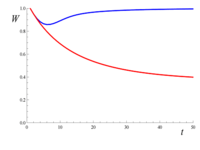

The example of inbreeding depression due to recessive lethals

As an example of genetic purging, consider a large population where there are recessive lethal alleles segregating at very low frequency in many loci, so that each individual carries on the average one of these alleles. Although about 63% of the individuals carry at least one of these lethal alleles, almost none carry two copies of the same lethal. Therefore, since lethals are considered completely recessive (i.e., they are harmless in heterozygosis), they cause almost no deaths. Now assume that population size reduces to a small value (say N=10), and remains that small for many generations. As inbreeding increases, the probability of being homozygous for one (or more) of these lethal alleles also increases, causing fitness to decline. However, as those lethals begin to occur in homozygosis, natural selection begins purging them. The figure to the right gives the expected decline of fitness against the number of generations, taking into account just the increase in inbreeding F (red line), or both inbreeding and purging (blue line, computed using the purged inbreeding coefficient g). This example shows that purging can be very efficient preventing inbreeding depression. However, for non-lethal deleterious alleles, the efficiency of purging would be smaller, and it can require larger populations to overcome genetic drift.

Genome renewal

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces paradoxus have a life cycle that alternates between long periods of asexual reproduction as a diploid, ending in meiosis that is usually immediately followed selfing, with only rare outcrossing.[7] Recessive deleterious mutations accumulate during the diploid expansion phase, and are purged during selfing: this purging has been termed "genome renewal".[8][9]

Evidence and problems

When a previously stable population undergoes inbreeding, if nothing else changes, natural selection should consist mainly of purging. The joint consequences of inbreeding and purging on fitness vary depending on many factors: the previous history of the population, the rate of increase of inbreeding, the harshness of the environment or of the competitive conditions, etc. The effects of purging were first noted by Darwin[10] in plants, and have been detected in laboratory experiments and in vertebrate populations undergoing inbreeding in zoos or in the wild, as well as in humans.[11] The detection of purging is often obscured by many factors, but there is consistent evidence that, in agreement with the predictions explained above, slow inbreeding results in more efficient purging, so that a given inbreeding F leads to less threat to population viability if it has been produced more slowly.[12]

Nevertheless, in practical situations, the genetic change in fitness also depends on many other factors, besides inbreeding and purging. For example, adaptation to changing environmental conditions often causes relevant genetic changes during inbreeding. Furthermore, if inbreeding is due to a reduction in population size, selection against new deleterious mutations can become less efficient, and this can induce additional fitness decline in the medium-long term.

In addition, part of the inbreeding depression could not be due to deleterious alleles, but to an intrinsic advantage of being heterozygous compared to being homozygous for any available allele, which is known as overdominance. Inbreeding depression caused by overdominance cannot be purged, but seems to be a minor cause of overall inbreeding depression, although its actual importance is still a matter of debate.[13]

Therefore, predicting the actual evolution of fitness during inbreeding is highly elusive. However, the component of fitness decline expected from inbreeding and purging on deleterious alleles could be predicted using g.

References

- Garcia-Dorado, A. (15 April 2015). "On the consequences of ignoring purging on genetic recommendations of MVP rules". Heredity. 115: 185–187. doi:10.1038/hdy.2015.28. PMC 4814235. PMID 25873145.

- Glémin, S (2003). "How are deleterious mutations purged? Drift versus nonrandom mating". Evolution. 57: 2678–2687. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01512.x. PMID 14761049.

- Hedrick, P. W.; Kalinowski, S. T. (2000). "Inbreeding depression in conservation biology". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 31: 139–162. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.139.

- García-Dorado, A (2012). "Understanding and predicting the fitness decline of shrunk populations: inbreeding, purging, mutation and standard selection". Genetics. 190: 1461–1476. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.135541. PMC 3316656. PMID 22298709.

- Frankham, R (2005). "Genetics and extinction". Biological Conservation. 126: 131–140. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.05.002.

- Crow, J.F.; Kimura, M. (1970). An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. NY: Harper & Row.

- Tsai, I. J.; Bensasson, D.; Burt, A.; Koufopanou, V. (14 March 2008). "Population genomics of the wild yeast Saccharomyces paradoxus: Quantifying the life cycle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (12): 4957–4962. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707314105. PMC 2290798. PMID 18344325.

- Mortimer, Robert K.; Romano, Patrizia; Suzzi, Giovanna; Polsinelli, Mario (December 1994). "Genome renewal: A new phenomenon revealed from a genetic study of 43 strains ofSaccharomyces cerevisiae derived from natural fermentation of grape musts". Yeast. 10 (12): 1543–1552. doi:10.1002/yea.320101203. PMID 7725789.

- Masel, Joanna; Lyttle, David N. (December 2011). "The consequences of rare sexual reproduction by means of selfing in an otherwise clonally reproducing species". Theoretical Population Biology. 80 (4): 317–322. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2011.08.004. PMC 3218209. PMID 21888925.

- Darwin, C. R. (1876). The effects of cross and selffertilisation in the vegetable kingdom. London: John Murray.

- Crnokrak, P.; Barrett, S. C. H. (2002). "Purging the genetic load: a review of the experimental evidence". Evolution. 56: 2347–2358. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00160.x.

- Leberg, P. L.; Firmin, B. D. (2008). "Role of inbreeding depression and purging in captive breeding and restoration programmes". Molecular Ecology. 17: 334–343. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2007.03433.x. PMID 18173505.

- Crow, JF (2008). "Mid-century controversies in population genetics". Annual Review of Genetics. 42: 1–16. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091612. PMID 18652542.