Species translocation

Translocation in wildlife conservation is the capture, transport and release or introduction of species, habitats or other ecological material (such as soil) from one location to another. It contrasts with reintroduction, a term which is generally used to denote the introduction into the wild of species from captive stock.

Translocation is an effective management strategy and important topic in conservation biology. It decreases the risk of extinction by increasing the range of a species, augmenting the numbers in a critical population, or establishing new populations thus reducing the risk of extinction.[2] This improves the level of biodiversity in the ecosystem.

Translocation may be expensive and is often subject to public scrutiny,[3] particularly when the species involved is charismatic or perceived as dangerous (for example wolf reintroduction).[4] Translocation as a tool is used to reduce the risk of a catastrophe to a species with a single population[5][6], to improve genetic heterogeneity of separated populations of a species, to aid the natural recovery of a species or re-establish a species where barriers might prevent it from doing so naturally.[7] It is also used to move ecological features out of the way of development.

Several critically endangered plant species in the southwestern Western Australia have either been considered for translocation or trialled. Grevillea scapigera is one such case, threatened by rabbits, dieback and degraded habitat.[8]

Three types

The first of three types of translocation is introduction. Introduction is the deliberate or accidental translocation of a species into the wild in areas where it does not occur naturally. Introduction of non-native species occurs for a variety of reasons. Examples are economic gain (Sitka Spruce), controlling crop pests (cane toads),[9] improvement of hunting and fishing (fallow deer), ornamentation of roads (rhododendron) or maintenance (sweet chestnut). In the past, the costs of translocation introductions of non-native species to ecosystems far outweighed the benefits of them.[10] For example, eucalyptus trees were introduced in California during the Gold Rush as a fast-growing timber source. By the early 1900s, however, this did not happen because of early harvesting and the splitting and twisting of cut wood. Now the introduction of non-native eucalyptus, particularly in the Oakland Hills is causing competition among native plants and encroaching on habitat for natural wildlife.

The second of the three types of translocation is re-introduction. Re-introduction is the deliberate or accidental translocation of a species into the wild in areas where it was indigenous at some point, but no longer at the present. Re-introduction is used as a wildlife management tool for the restoration of an original habitat when it has become altered or species have become extinct due to over-collecting, over-harvesting, human persecution, or habitat deterioration. An example of a successful translocation was the one performed with the plant Narcissus cavanillesii to prevent its flooding due to the construction of a dam.[11]

Lastly, the third type of translocation is re-stocking. Re-stocking is the translocation of an organism into the wild into an area where it is already present. Re-stocking is considered as a conservation strategy where populations have dropped below critical levels and species recovery is questionable due to slow reproductive rates or inbreeding. The World Conservation Union recommends that re-stocking only occur when the causes of population decline have been removed, the area has the capacity to sustain the desired population, and individuals are of the same race as the population into which they are released but not from genetically impoverished or cloned stock.

Trends

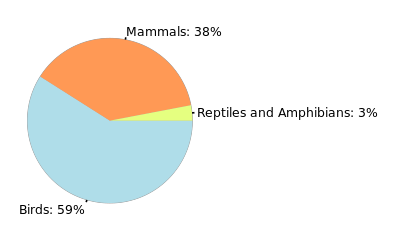

Between 1973 and 1989 an estimated 515 translocations occurred per year in the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia.[12] The majority were conducted in the United States. Birds were the most frequently translocated, followed by threatened and endangered species, then non-game species.[13] Of the 261 translocations in the United States reported wild species were most frequently translocated, and the greatest number occurred in the Southeast.

Programs in action today: Western Shield

Western Shield, of Australia, is a nature conservation program which plays an important role in protecting Australia’s native animal population. More importantly, Western Shield also has programs specializing in translocation of endangered and threatened animals. Founded in 1996, it's the most successful wildlife conservation program in Australia and in 2006, it still remains among the largest in the world. The program has already had significant success: three native mammals in Australia – the woylie, quenda and tammar wallaby – have been removed from the threatened species list, many populations of native animals have recovered or been re-established in their former ranges, and the restoration of ecological processes has begun. From 1996 to 2000, Western Shield has taken part of 60 translocations, mostly introductions, of 17 species all over the country on private and interstate lands.[14]

Translocation success

Species translocation can vary greatly across taxa. For instance, bird and mammal translocations have a high success rate, while amphibian and reptile translocations have a low success rate.[15] Successful translocations are characterized by moving a large number of individuals, using a wild population as the source of the translocated individuals, and removing the problems which caused their decline within the area they are being translocated.[16] The translocation of 254 black bears to the Ozark Mountains in Arkansas resulted in more than 2,500 individuals 11 years later and has been seen as one of the most successful translocations in order Carnivora.[17] Another example of successful translocation is the gray wolf translocation in Yellowstone National Park.

Reasons for failures

Often, when conducting translocation programs, differences in specific habitat types between the source and release sites are not evaluated as long as the release site contains suitable habitat for the species. Translocations could be especially damaging to endangered species citing the failed attempt of Bufo hemiophys baxteri in Wyoming and B. boreas in the Southern Rocky Mountains.[18] For species that have declined over large areas and long periods of time translocations are of little use. Maintaining a large and widely dispersed population of amphibians and other species is the most important aspect of maintaining regional diversity and translocation should only be attempted when a suitable unoccupied habitat exists.[19] Among plants, the translocation of Narcissus cavanillesii during the construction of the largest European dam (Alqueva dam) is considered one of the best known examples of a successful translocation in plants [20].

References

- "African Savanna: Giraffe Fact Sheet". National Zoo - Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Rout, T. M., C. E. Hauser and H. P. Possingham. Optimal translocation strategies for threatened species. http://www.mssanz.org.au/modsim05/papers/rout.pdf. 2007. Accessed on 11 May 2007.

- Griffith, B.; Scott, J. M.; Carpenter, J. W.; Reed, C. (1989). "Translocation as a Species Conservation Tool: Status and Strategy". Science. 245 (4917): 477–480. Bibcode:1989Sci...245..477G. doi:10.1126/science.245.4917.477. PMID 17750257.

- Bath, AJ (1989). "The public and wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park". Society and Natural Resources. 2 (4): 297–306. doi:10.1080/08941928909380693.

- Draper, David; Marques, Isabel; Iriondo, José María (2019-07-01). "Species distribution models with field validation, a key approach for successful selection of receptor sites in conservation translocations". Global Ecology and Conservation. 19: e00653. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00653. ISSN 2351-9894.

- Draper Munt, David; Marques, Isabel; Iriondo, José M. (2016-02-01). "Acquiring baseline information for successful plant translocations when there is no time to lose: the case of the neglected Critically Endangered Narcissus cavanillesii (Amaryllidaceae)". Plant Ecology. 217 (2): 193–206. doi:10.1007/s11258-015-0524-2. ISSN 1573-5052.

- Shirey, P.D.; Lamberti, G.A. (2010). "Assisted colonization under the U.S. Endangered Species Act". Conservation Letters. 3 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263x.2009.00083.x. Archived from the original on 2011-04-26.

- Anne Cochrane; Andrew Crawford; Amanda Shade; Bryan Shearer (2008). "Corrigin Grevillea (Grevillea scapigera) Interim Recovery Plan 224" (PDF). Department of Environment and Conservation website. Kensington, WA: Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australian Government. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Urban, Mark; Phillips, Ben; Skelly, David; Shine, Richard (2007). "The cane toad's (Chaunus [Bufo] marinus) increasing ability to invade Australia is revealed by a dynamically updated range model". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 274 (1616): 1413–1419. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0114. PMC 2176198. PMID 17389221.

- Holdgate, M. (1999) Lancaster: British Association of Nature Conservationists/National Trust Conference - Nature in Transition.

- Munt, David Draper; Marques, Isabel; Iriondo, José M. (2016-02-01). "Acquiring baseline information for successful plant translocations when there is no time to lose: the case of the neglected Critically Endangered Narcissus cavanillesii (Amaryllidaceae)". Plant Ecology. 217 (2): 193–206. doi:10.1007/s11258-015-0524-2. ISSN 1385-0237.

- Griffith, B.; Scott, J.M.; Carpenter, J.W.; Reed, C. (1989). "Translocation as a species conservation tool: status and strategy". Science. 245 (4917): 477–480. Bibcode:1989Sci...245..477G. doi:10.1126/science.245.4917.477. PMID 17750257.

- Griffith, B.; Scott, J.M.; Carpenter, J.W.; Reed, C. (1993). "Animal translocations and potential disease transmission". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 24: 231–236.

- McNamara, Keiran. 2004. Western Shield. Conservation Science W. Australia. 5(2): 1

- Dodd, C. Kenneth; Seigel, Richard (1991). "Relocation, Repatriation, and Translocation of Amphibians and Reptiles : Are They Conservation Strategies That Work ?". Herpetologica. 47: 336–350.

- Fisher, J; Lindenmayer, D.B. (2000). "An assessment of the published results of animal relocations". Biological Conservation. 96: 1–11. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(00)00048-3.

- Smith, Kimberly; Clark, Joseph (1994). "Black bears in Arkansas: classification of a successful translocation". American Society of Mammalogists. 75 (2): 309–320. doi:10.2307/1382549. JSTOR 1382549.

- Muths, E., T. L. Johnson, and P. S. Corn. 2001. Experimental repatriation of boreal toad (Bufo boreas) eggs, metamorphs, and adults in Rocky Mountain National Park. Southwestern Naturalist 46: 106–113.

- Trenham, Peter C.; Marsh, David M. (2002). "Amphibian Translocation Programs: Reply to Seigel and Dodd". Conservation Biology. 16 (2): 555–556. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.01462.x.

- Draper Munt, David; Marques, Isabel; Iriondo, José M. (2016-02-01). "Acquiring baseline information for successful plant translocations when there is no time to lose: the case of the neglected Critically Endangered Narcissus cavanillesii (Amaryllidaceae)". Plant Ecology. 217 (2): 193–206. doi:10.1007/s11258-015-0524-2. ISSN 1573-5052.

Further reading

- Griffith, Brad; Scott, Michael; Carpenter, James; Reed, Christine (1989). "Translocation as a species conservation tool: status and strategy". Science. 245 (4917): 477–480. Bibcode:1989Sci...245..477G. doi:10.1126/science.245.4917.477. PMID 17750257.

- National Biological Service, United States. (1995-09-11). Our Living Resources: A Report to the Nation on the Distribution, Abundance, and Health of U.S. Plants, Animals, and Ecosystems. Government Printing Office. pp. 405–407. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- Ruffell, Jay; Guilbert, Joshua; Parsons, Stuart (2009). "Translocation of bats as a conservation strategy : previous attempts and potential problems". Endangered Species Research. 8: 25–31. doi:10.3354/esr00195.