Gelsemine

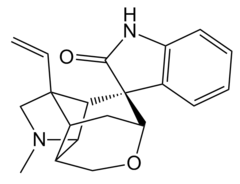

Gelsemine (C20H22N2O2) is an indole alkaloid isolated from flowering plants of the genus Gelsemium, a plant native to the subtropical and tropical Americas, and southeast Asia, and is a highly toxic compound that acts as a paralytic, exposure to which can result in death. It has generally potent activity as an agonist of the mammalian glycine receptor, the activation of which leads to an inhibitory postsynaptic potential in neurons following chloride ion influx, and systemically, to muscle relaxation of varying intensity and deleterious effect. Despite its danger and toxicity, recent pharmacological research has suggested that the biological activities of this compound may offer opportunities for developing treatments related to xenobiotic- or diet-induced oxidative stress, and of anxiety and other conditions, with ongoing research including attempts to identify safer derivatives and analogs to make use of gelsemine's beneficial effects.

Gelsemine (gelsemin), an indole alkaloid | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.360 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H22N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 322.408 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Natural sources

Gelsemine is found in, and can be isolated from, the subtropical to tropical flowering plant genus Gelsemium, family Loganiaceae, which as of 2014 included five species, where G. sempervirens Ait., the type species, is prevalent in the Americas and G. elegans Benth. in China and East Asia,[1][2] The species in the Americas, G. sempervirans, has a number of common names that include yellow or Carolina jasmine (or jessamine), gelsemium, evening trumpetflower, and woodbine.[3][4] The plant genus is native to the subtropical and tropical Americas, e.g., in Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, and Belize,[2] as well as to China and southeast Asia.[2] The species is prized for its "heavily fragrant yellow flowers," and has been cultivated since mid-seventeenth century (in Europe).[2] It is found in southeastern and south-central states of the U.S.,[3] and as a garden plant in warmer areas where it can be trained to grow over arbors or to cover walls (see image).[5]

All plant parts of the herbage and exudates of this genus, including its sap and nectar, appear to contain gelsemine and related compounds,[6] as well as a wide variety of further alkaloids and other natural products.[1] The plant's herbage, in particular, is known to contain several toxic alkaloids, and is generally known to be poisonous to livestock and humans.[2]

Chemistry

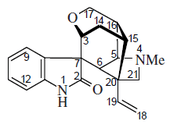

Gelsemine was isolated from G. sempervirens Ait., in 1870.[7][8] Its chemical formula was determined to be C20H22N2O2, thus with a molecular weight of 322.44 g/mol.[9] Its structure was finally determined, by X-ray crystallographic analysis and by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, in 1959 by Conroy and Chakrabarti.[10][7][8]

It is a monoterpenoid type of indole alkaloid,[11] and a close relative of the natural product gelseminine, which is also present from the same natural sources.[6] The gelsemine class of alkaloids are some of a wide variety of the alkaloid and other natural products that have been isolated from this genus of plants.[1]

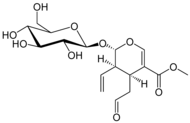

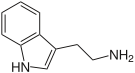

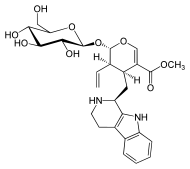

Gelsemine's biosynthesis, as of 1998, is thought to proceed from 3α(S)-strictosidine (isovincoside), the common precursor for essentially all monoterpenoid indole alkaloids—itself deriving directly from mevalonic acid-derived secologanin and tryptamine.[12][11]:p. 629 From strictosidine, the biosynthesis proceeds through five intermediates—including koumicine (akkuammidine), koumidine, vobasindiol, anhydrovobasindiol, and gelsenidine (humantienine-type).[11]:p. 629[13] The related alkaloids koumine and gelsemicine also derive from this pathway (koumine from anhydrovobasindiol via oxidation and rearrangement, and gelsemicine from gelsemine itself, via aromatic oxidation and O-methylation).[11]:p. 629 [13]:p. 132ff For the chemical synthesis (natural product synthesis, studies and total synthesis), see the separate section below.

Summary of biological activities

Full sections in following are devoted to specific activities of gelsemine. Noted are the facts that it is a highly toxic compound, where exposure can result in paralysis and death. It is reported to be a glycine receptor agonist with significantly higher binding affinity for some of these receptors than its native agonist, glycine. In addition, it has been shown to have effects on pathways/systems in model animals (rat, rabbit), related to xenobiotic- or diet-induced oxidative stress, and in the treatment of anxiety and other conditions.

History

Gelsimium extracts, and so gelsemine, indirectly, have been the subject of serious scientific study for over a hundred years. On the medical side, gelsemium tinctures were used in the treatment of neuralgia by physicians in England, in the late 19th century; Arthur Conan Doyle, the noted author who first trained as a physician, after observing the success of such treatments, ingested increasing doses of a tincture daily, to “ascertain how far one might go in taking the drug, and what the primary symptoms of an overdose might be,” submitting his first career publication on this in the British Medical Journal.[14][primary source] On the chemistry side, the December 1910 meeting of the Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, of the American Chemical Society, reports among the papers read, the "Assay of Gelsemium" by L.E. Sayre.[15][primary source]

Mechanisms of action

Gelsemine is an agonist for the glycine receptor (GlyR) with a much greater affinity for studied examples of this receptor than glycine. When glycine receptors are activated, chloride ions enter the neuron causing an inhibitory postsynaptic potential, which, systemically, leads to muscle relaxation.[16][primary source]

Toxicity and toxicology

The plant Gelsemium sempervirens is known to be toxic, and there are serious safety concerns with regard exposure to it.[17] Exposure resulting in toxicity can be via ingestion or injection (subcutaneous or intraperitoneal). It has been shown to have LD50s of 49 mg/kg intraperitoneal in mice, and of 0.1 mg/kg subcutaneous in rabbits. The sap of the plant may cause skin irritation in sensitive individuals, and there are reports that inhalation from the flowers alone may, in some cases, lead to human poisoning (see below, where insect death at such flowers is likewise reported).[2]

The plant's herbage is known to contain several toxic alkaloids, and while there is report of its feeding to pigs, it is generally considered to be an abortifacient and lethal poison when livestock or other animals feed on its leaves.[2] It has been reportedly used as a fish poison as well, e.g., on the island of Borneo.[2]

Human poisonings are known, including pediatric and adult cases, and in the case of adults, both accidental and intentional poisonings. At lower doses in humans, the inhibitory postsynaptic potential induced by gelsemine action at the glycine receptor can result in nausea, diarrhea and muscle spasms caused by loss of involuntary muscle control; at higher doses, vision impairment or blindness, paralysis, and death can occur. Children, mistaking the flower of G. sempervirens for honeysuckle, have been poisoned by sucking the nectar from the flower; its ingestion has been associated with honey bee (but not bumble bee) fatalities as well (e.g., in the southeast U.S.).[18][2][19] It has been reportedly used, via ingestion or smoking, as a poison in cases of suicide, in China, Vietnam, and Borneo.[2]

Treatment

Gelsemine is a highly toxic and therefore possibly fatal substance for which there is no antidote, but the symptoms can be managed in low dose intoxications. In the case of an oral exposure a gastric lavage is performed, which must be done within approximately one hour of ingestion. Activated charcoal is then administered to bind the free toxin in the gastrointestinal tract to prevent absorption. Benzodiazepine or phenobarbital is also generally administered to help control seizing, and atropine can be used to treat bradycardia. Electrolyte and nutrient levels are monitored and controlled.[9]

In the case of a skin exposure, the area is washed with soap and water for 15 minutes to avoid skin damage.[9]

While there is no current treatment to reverse the effects of gelsemine poisoning, preliminary research has suggested that strychnine has potential therapeutic applications due to its antagonistic effects at the glycine receptor.[20][primary source]

Chemical synthesis

The chemical synthesis of gelsemine has been an active target of interest since the early 1990s, given its place among the alkaloids, and its complex structure (seven contiguous stereocenters and six rings).[7] Its first racemic total synthesis was in 1994, by W.N. Speckamp's group, with a remarkable first yield of 0.83% (given the subsequent range, prior to 2014, of 0.02-1.2%).[21][7]

Eight further total syntheses have been reported in the literature, including from the groups of A.P. Johnson in 1994, T. Fukuyama in 1996 and again in 2000, D.J. Hart in 1997, L.E. Overman in 1999, S.J. Danishefsky in 2002, and Y. Qin in 2012, with the latter Fukuyama group synthesis (31 steps, 0.86%) and the Qin group synthesis (25 steps, 1%) being asymmetric.[7] A further asymmetric synthesis using an organocatalytic Diels–Alder approach from the F.G. Qiu and H. Zhai groups in China, reporting a remarkable 12 steps and a 5% yield, was reported in 2015.[7]

Potential medical applications

Modern medical utility

Pharmacological research has suggested gelsemine activities to have potential related to the treatment of anxiety, and in treatments of conditions involving oxidative stress. In addition, gelsemine has been noted to have anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities. Recent research on gelsemine has included investigations aimed at developing safer gelsemine analogs and derivatives that might allow safe application of the compounds beneficial effects.

The identified anxiolytic effects of preparations derived from Gelsemium sempervirens are believed due to in largest part to the presence of gelsemine in such preparations.[22] Based on a rat study, use of gelsemine has been reported as being potentially effective, where the comparison was to treatment with Diazepam.[20][primary source]

Gelsemine has been suggested to have potential in offering protective effects against oxidative stress. In a small rat study, the off-target effects of cisplatin—nephrotoxicity arising from its induction of pathways that generate reactive oxygen species, a factor impacting its use in cancer treatment—were examined, and gelsemine was found to significantly attenuate cisplatin-induced damage to DNA, and further general damage due to oxidative mechanisms. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase and lipid peroxidation activities were noted, along with "increased production and/or activity of anti-oxidants, both enzymatic... and non-enzymatic...".[23][primary source]

In a small rabbit study, the impact of gelsemine administration on parameters relating to diet-induced hyperlipidemia was examined, where gelsemine was observed to improve lipid profile parameters associated with hyperlipidemia to a significant extent, as well as to "decreas[e] hyperlipidemia-induced oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner," as determined by altered activities of a number of relevant metabolite and enzyme activity levels. The results, taken together, led the study authors to conclude that supplements of gelsemine to animals exposed to high fat diets may be of use in reversing the effects and in protecting tissues from oxidative stress resulting from such diets.[24][primary source]

Gelsemine has been observed to have anti-inflammatory activity.[23][primary source]

Gelsemine has been observed to have anti-cancer activity.[23][primary source]

Traditional medical uses

Preparations from the plant from which gelsemine derives, Gelsemium sempervirens, have been used as treatment for a variety of ailments, for instance, through use of Gelsemium tinctures. Applications have included treatment of acne, anxiety, ear pain, migraine, and more generally with diseases associated with an inflammatory response, and in cases of abnormal nervous function (paralysis, “pins and needles” feeling, neuralgia, etc.).[25][primary source]

Popular culture

Gelsemine is used indirectly, via use of "yellow jasmine", in the 1927 Agatha Christie novel, The Big Four, where an injection of this natural preparation is used to kill the character Mr Paynter.[26] It is then used directly, in 2013, as gelsemine, in series 13 of the ITV series, Agatha Christie's Poirot, as the agent to immobilize the character Stephen Paynter (played by Steven Pacey) before his being burnt to death, thus implicating the character Madame Olivier, a research neuroscientist (played by Patricia Hodge); and also, directly, to paralyze and immobilise Olivier and another character after their kidnappings.[27]

In House of Cards season 5 episode 12, Jane Davis offers Claire Underwood gelsemium as a headache reliever, noting that she should only use two drops. Later on Claire uses the gelsemine to murder Tom Yates, her lover, by putting it into his drink without his knowledge.[28]

In episode 9 of season 3 of iZombie, the victim is poisoned by gelsemine.[29]

See also

References

- Zhang, Jing-Yang; Wang, Yong X. (2014). "Gelsemium Analgesia and the Spinal Glycine Receptor/Allopregnanolone Pathway". Fitoterapia. 100 (C, November): 35–43. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.002. PMID 25447163.

- Ornduff, R. (1970). "The Systematics and Breeding System of Gelsemium (Loganiceae)" (review). Journal of the Arnold Arboretum. 51 (1): 1–17. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.7036. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Gelsemium sempervirens". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- USF-PA Staff (February 18, 2017). "Gelsemium sempervirens" (database entry). Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants. University of South Florida. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Gelsemium sempervirens Carolina jessamine from New Moon Nurseries". www.newmoonnursery.com. New Moon Nursery.

- Drugs.com Staff (2009). "Gelsemium sempervirens" (database entry). Drugs.com. Alphen aan den Rijn, NLD: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Chen, X.; Duan, S.; Tao, C.; Zhai, H.; Qiu, F.G. (2015). "Total Synthesis of (+)-Gelsemine Via an Organocatalytic Diels–Alder Approach". Nature Communications. 6 (7204): 7204. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6E7204C. doi:10.1038/ncomms8204. PMC 4647982. PMID 25995149. Note, the use of Chen et al. is, in part, for the thorough manner in which it reviews the earlier literature on synthetic efforts toward, and total syntheses of the gelsemine target.

- Lin, H; Danishefsky, SJ (3 January 2003). "Gelsemine: a thought-provoking target for total synthesis". Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. In English). 42 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1002/anie.200390048. PMID 19757588.

- Hazardous Substances Data Bank [Internet] (November 8, 2002). "Gelsemine. Hazardous Substances Databank Number: 3488" (database entry). Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Conroy, Harold; Chakrabarti, J.K. (January 1959). "NMR spectra of gelsemine derivatives. The structure and biogenesis of the alkaloid gelsemine". Tetrahedron Letters. 1 (4): 6–13. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)82718-0.

- Seigler, David S. (1998). "Indole Alkaloids" (review). Plant Secondary Metabolism. Boston, MA: Kluwer/Springer. pp. 628–654, esp. 646ff. ISBN 978-0412019814. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "indole and ipecac alkaloid biosynthesis". qmul.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Liu, Z.-J.; Lu, R.-R. (1988). "Gelsemium Alkaloids" (review). The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology. The Alkaloids. 33. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 84–140, esp. 132ff. ISBN 978-0080865577. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Doyle, Arthur Conan (2009) [1879]. "Arthur Conan Doyle takes it to the limit (1879)". British Medical Journal. 339: b2861. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2861.[primary source]

- Murray, B.L. (1911). Kraemer, Henry (ed.). "Correspondence: American Chemical Society, Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry". The American Journal of Pharmacy. 83 (April): 194. Retrieved February 19, 2017.[primary source]

- Venard C, Boujedaini N, Belon P, Mensah-Nyagan AG, Patte-Mensah C (2008). "Regulation of Neurosteroid Allopregnanolone Biosynthesis in the Rat Spinal Cord by Glycine and the Alkaloidal Analogs Strychnine and Gelsemine". Neuroscience. 153 (1): 154–161. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.009. PMID 18367344.[primary source]

- WebMD Staff (February 19, 2017). "Gelsemium: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions and Warnings" (database entry). WebMD.com. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- Knight, Anthony; Walter, Richard (2001). A Guide to Plant Poisoning of Animals in North America. Manson Series. Jackson, WY: Teton NewMedia. ISBN 978-1893441118. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- In the case of Bombus impatiens (bumblebees), feeding on gelsemine may reduce the load of the parasite Crithidia bombi, which, in improving bee health, increases foraging efficiency, a possible case of selective advantage of a pollinator self-medicating through collection of an otherwise generally toxic secondary metabolite. See Manson, J.S.; Otterstatter, M.C.; Thomson, J.D. (2009). "Consumption of a Nectar Alkaloid Reduces Pathogen Load in Bumble Bees" (PDF). Oecologia. 162 (27 August): 81–89. doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1431-9. PMID 19711104. Retrieved February 18, 2017.[primary source]

- Meyer L; Boujedaini N; Patte-Mensah C; Mensah-Nyagan AG. (2013). "Pharmacological Effect of Gelsemine on Anxiety-Like Behavior in Rat". Behav Brain Res. 253 (September 15): 90–94. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2013.07.010. PMID 23850351.[primary source]

- Newcombe, N.J.; Ya, F.; Vijn, R.J.; Hiemstra, H.; Speckamp, W.N. (1994). "The Total Synthesis of (±)-Gelsemine". J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 0 (6): 767–768. doi:10.1039/C39940000767.[primary source]

- Chirumbolo, S. (2011). "Gelsemine and Gelsemium sempervirens L. Extracts in Animal Behavioral Test: Comments and Related Biases". Frontiers in Neurology. 31 (May 16): 31. doi:10.3389/fneur.2011.00031. PMC 3098419. PMID 21647210.

- Lin L; Zheng J; Zhu W; Jia N. (2015). "Nephroprotective effect of gelsemine against cisplatin-induced toxicity is mediated via attenuation of oxidative stress". Cell Biochem Biophys. 71 (2): 535–541. doi:10.1007/s12013-014-0231-y. PMID 25343941.[primary source]

- Wu T; Chen G; Chen X; Wang Q; Wang G. (2015). "Anti-Hyperlipidemic and Anti-Oxidative Effects of Gelsemine in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Rabbits". Cell Biochem Biophys. 71 (1): 337–344. doi:10.1007/s12013-014-0203-2. PMID 25213292.[primary source]

- Winterburn, George William (1883). "Gelsemium sempervirens". Transactions of the National Eclectic Medical Association. 10.[primary source]

- Christie, Agatha (1927). The Big Four. Glasgow, GBR: William Collins & Sons.

- Eirik (30 October 2013). "Investigating Agatha Christie's Poirot: Episode-by-episode: The Big Four". investigatingpoirot.blogspot.com. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "House of Cards (2013) s05e12". 2013.

- "iZombie (2015) s03e09 Episode Script". 2015.

Further reading

- Jin GL; Su YP; Liu M; Xu Y; Yang J; Liao KJ; Yu CX. (2014). "Medicinal Plants of the Genus Gelsemium (Gelsemiaceae, Gentianales)—A Review of Their Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology and Traditional Use". J Ethnopharmacol. 152 (1, February 27): 33–52. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.01.003. PMID 24434844.

- Patte-Mensah C; Meyer L; Taleb O; Mensah-Nyagan AG. (2014). "Potential Role of Allopregnanolone for a Safe and Effective Therapy of Neuropathic Pain". Prog Neurobiol. 113 (February): 70–78. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.004. PMID 23948490.

- Dutt, V.; Thakur, S.; Dhar, V.J.; Sharma, A. (2010). "The Genus Gelsemium: An Update". Pharmacognosy Reviews. 4 (8): 185–194. doi:10.4103/0973-7847.70916. PMC 3249920. PMID 22228960.

- Zhang, Jing-Yang; Wang, Yong X. (2014). "Gelsemium analgesia and the spinal glycine receptor/allopregnanolone pathway". Fitoterapia. 100 (C, November): 35–43. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.002. PMID 25447163.

- Austin, Joel (January 9, 2002), Comparative Syntheses of Gelsemine, MacMillan Group Meeting

- Brower, Justin (August 12, 2014), Gelsemium and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the Self-Poisoner, Nature's Poisons