Gaykhatu

Gaykhatu (Mongolian script:ᠭᠠᠶᠺᠠᠲᠦ; Mongolian: Гайхат, romanized: Gaikhat, lit. 'Surprising') was the fifth Ilkhanate ruler in Iran. He reigned from 1291 to 1295. His Buddhist baghshi gave him the Tibetan name Rinchindorj (Standard Tibetan: རིན་ཆེན་རྡོ་རྗེ, lit. 'Jewel Diamond') which was appeared on his paper money.

| Gaykhatu | |

|---|---|

Gaykhatu enthroned, 15th century miniature | |

| Il-khan | |

| Reign | 1291–1295 |

| Coronation | 23 July 1291 Ahlat |

| Predecessor | Arghun |

| Successor | Baydu |

| Viceroy of Anatolia | |

| Reign | 1284 - 1291 |

| Predecessor | Qonqurtai |

| Successor | Samagar |

| Co-ruler | Hulachu (1284-1286) |

| Born | c. 1259 |

| Died | 21 March 1295 (aged 35–36) |

| Spouse | Padishah Khatun |

| Dynasty | Borjigin |

| Father | Abaqa Khan |

| Mother | Nukdan Khatun |

| Religion | Buddhism |

Early life

He was born to Abaqa and Nukdan Khatun, a Tatar lady in c.1259[1]. He was living in Jazira during Tekuder's reign and had to flee to Arghun in Khorasan after Qonqurtai's execution in 1284.[2] He was given as hostage to Tekuder by Arghun as a condition of truce in June 1284 and put in orda of Todai Khatun, his step-mother.[3] After Arghun's enthroment, he was confirmed as governor of Anatolia together with his uncle Hulachu.

Rule in Anatolia

He was stationed in Erzinjan and learnt to speak Persian and to some degree Turkish during his stay in Anatolia. Gaykhatu ruled Anatolia solely after recall of Hulachu to Iran in 1286.[4] It was then he was married to Padishah Khatun, a princess of Qutlugh-Khanids. He aided Masud II on his campaigns against Turkmen principalities, most importantly Germiyanids. Using this opportunity, Karamanids invaded Mongol allies of Cilician Armenia during his campaign. Gaykhatu was sent in turn by Arghun to help Leo II against Güneri of Karaman in 1286, who had captured Tarsus from Cilician Kingdom. Gaykhatu invaded and burned his capital Karaman on 16 January 1287[4], forcing Güneri to retreat to mountains.[5]Gaykhatu's viceroyalty was briefly interrupted by appointment of Samagar from 1289 to 1290. He resumed his activities when Samagar was arrested on 15 October 1290 in Tokat on charges of corruption and was sent back to Iran. Gaykhatu visited Konya on 3 January 1291, confirming appointment of his new tax officer Khwaja Nasir ud-Din and conduction of a new general census.

Reign

Gaykhatu heard of Arghun's death in his wintering pastures near Antalya from Lagzi Küregen (son of Arghun Aqa and in-law of Hulagu Khan). The main contenders for the throne were his nephew Ghazan and cousin Baydu. Baydu was nominated for the throne by an influential Mongol commander, Ta'achar, who had sent an envoy to Gaykhatu falsely announcing that Baydu had already taken the throne. Suspicious, Gaykhatu headed to the qurultai.

While nobles like Taghachar, Qoncuqbal, Toghan and Tuqal supported Baydu, historians suggest Baydu simply refused the throne stating it belonged to the brother or a son according to yassa[4]. Another source, Mahmud Aqsarai said that Baydu didn't appear at the quriltai at all.[6] The other contender to the throne, Ghazan, was engaged in a rebellion with Nawrūz (another son of Arghun Aqa), and couldn't attend the qurultai either, thus losing a bid to throne. As a consequence, Gaykhatu was elected il-khan on 23 July 1291, Ahlat. Gaikhatu's main supporter was his new wife Uruk Khatun - widow of Arghun and mother of Öljaitü.[7]

His first orders upon taking throne was to punish several emirs including Taghachar and Tuqal. Taghachar's (or in some sources, Qoncuqbal's) 10.000 army was given to Shiktur Noyan of Jalairs, while Tuqal's army was given to an amir named Narin Ahmad. Another Baydu supporter, Toghan was arrested on his way to escape to Khorasan. Meanwhile a rebellion by Turkmen emirs started in Anatolia, Gaykhatu had to move into his former domains, appointing Shiktur Noyan as regent of the state while confirming Anbarchi (son of Möngke Temür) as viceroy of East stationed in Ray.

Rebellion of Afrasiyab

Hazaraspid ruler Afrasiab I took the opportunity to extend his rule to Isfahan upon hearing of Arghun's death in 1291. Gaykhatu's retribution was brutal, sending a commander of his personal keshig Tuladai to pillage Lorestan who obtained Afrasiab's submission.[4] Gaykhatu's wives Padshah and Uruk interceded on behalf of Afrasiab, asking for forgiveness.[8] As a consequence, while Afrasiab was reinstated as ruler of Lorestan, his brother Ahmad was held at Ilkhanid court as hostage.

Campaign in Anatolia

Gaykhatu left for Anatolia in pursuit of the Karamanids who were besieging Konya on 31 August 1291 with 20.000 men.[9] Despite Konya was enforced by a brother of Masud II and Sahib Ataids, the Karamanids didn't leave until Gaykhatu's arrival at Kayseri. Gaykhatu divided his army into two, sending a part to Menteshe, while he himself raided the Karamanid capital Ereğli. His next target was Eshrefid beylik to the west, from whom he captured 7000 women and children, sending them to Konya.

After returning to Kayseri, he sent Goktai and Girai noyans to punish former supporters of Kilij Arslan IV in northern Anatolia accompanied by Seljuk armies. Using this opportunity, the Karamanids and Eshrefids again besieged Konya, but withdrew their armies when Henry II of Cyprus besieged Alaiye with 15 ships. Gaykhatu continued on to capture Denizli and looted the city for 3 days.[9] Masud also went on to fight against Kilij Arslan who was supported by Masud's brothers Faramurz and Kayumars in addition to the Chobanids. Gaykhatu sent an additional 3000 men with commanders Goktai, Girai and Anit. It was Girai and Temür Yaman Jandar who rescued Masud II from Turkmen captivity. Temür Yaman Jandar was granted the former Chobanid city of Kastamonu by Gaykhatu as an iqta due to this service.

Return to Iran

Gaykhatu spent 11 months in the Anatolian campaign and went back to Iran in May/June 1292. His absence in Iran was followed by a conspiracy led by Taghachar and his follower Sad al-Din Zanjani. They falsely informed viceroy Anbarchi - via Sad al-Din's brother Qutb al-Din, who was Anbarchi's vizier - of Gaykhatu's defeat by Turkmens in Anatolia and called him to take the throne. While ambitious, Anbarchi regarded this news with suspicion. After contacting Shiktur Noyan who was residing near Karachal[1], Anbarchi had them imprisoned by Shiktur. Gaykhatu arrived at Aladagh on 29 June 1292, had a second enthronement, possibly receiving a confirmation from Kublai Khagan.[11]

Upon returning, Gaykhatu allowed his wife Padishah Khatun's to gain Kirman in October 1292. He pardoned both Taghachar and Sad al-Din Zanjani, even appointing the latter to the post of vizier on 18 November 1292 while confirming his father-in-law Aq Buqa Jalair as commander-in-chief. Shiktur and Taghachar were subordinated to him. Sad al-Din also managed to get his brother Qutb al-Din to be appointed as governor of Tabriz.[12] Amassing huge amount of power and wealth in his hand, Sad al-Din became the real ruler of the Ilkhanate with personal army of 10.000, while gaining certain enemies as well. Former emirs Hasan and Taiju attempted to accuse him of embezzlement of state funds unsuccessfully.

In 1292, Gaykhatu sent a message to the Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Al-Ashraf Khalil, threatening to conquer the whole of the Levant if he didn't return Aleppo. Al-Ashraf replied: "The khan has the same ideas as me. I too hope to bring back Baghdad to the fold of Islam as previously. We will see which of us two will be quicker".[13] However, there were no major battles between Mongols and Mamluks afterwards.

During his reign, the princess Kökötchin arrived from the court of his Khagan Kublai in 1293, escorted by Marco Polo. The new Ilkhan decreed that the princess be married to his nephew Ghazan, who had fully supported his right to rule. Ghazan on the other hand sent a tiger to Gaykhatu as an answer. Marco Polo and his entourage stayed with Gaykhatu for nine months.

The Golden Horde khan Toqta, who ascended the throne at the same time as Gaykhatu, sent Prince Qalintay and Pulad as envoys to the Ilkhanate on 28 March 1294 to make a truce and possibly ask for help against Toqta's rivals. They returned to Golden Horde three days later.[4]

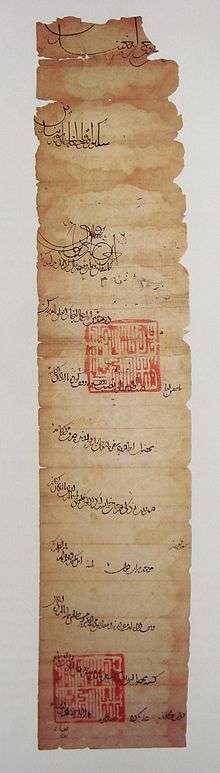

Introduction of paper money

In 1294, Gaykhatu wanted to replenish his treasury emptied by a great cattle plague. In response, his vizier Sad al-Din Zanjani[11] proposed the introduction of a recent Chinese invention called Jiaochao (paper money). Gaykhatu agreed and called for Kublai Khan's ambassador Bolad in Tabriz. After the ambassador showed how the system worked, Gaykhatu printed banknotes which imitated the Chinese ones so closely that they even had Chinese words printed on them. The Muslim confession of faith was printed on the banknotes to placate local sentiment. Gaykhatu's Buddhist name Rinchindorj was also present on money. Shiktur Noyan objected to introduction, calling this a foul attempt. First circulation started on 12 September 1294 in Tabriz. Gaykhatu ordered anyone who is going to refuse to use money to be executed on the spot. Poets, including Wassaf started to praise chao in order to appease Gaykhatu.[1]Paper moneys circulated were worth from half dirham to 10 dinars.

The plan was to get his subjects to use only paper money, and allow Gaykhatu to control the treasury. The experiment was a complete failure, as the people and merchants refused to accept the banknotes. Soon, bazaar riots broke out, economic activities came to a standstill, and the Persian historian Rashid ud-din speaks even of "'the ruin of Basra' which ensued upon the emission of the new money".[14] Gaykhatu had no choice but to withdraw the use of paper money.

Revolt of Baydu

Gaykhatu insulted Baydu telling one of his servants to hit Baydu while being drunk. This grew a resentment in Baydu towards him. Baydu left hastily towards to his appanage near Baghdad leaving his son Qipchak as a hostage in Gaykhatu's court. He was supported by Oirat emir Chichak (son of Sulaimish b. Tengiz Güregen), Lagzi Küregen (son of Arghun Aqa), El-Temur (son of Hinduqur Noyan) and Todachu Yarquchi, who followed him to Baghdad. He was also aided by his vizier Jamal ud-Din Dastgerdani. According to Hamdullah Qazwini, Baydu's main motivation on moving against Gaykhatu was his sexual advances against Qipchak.[15] When son-in-law Ghurbatai Güregen brought him news of treachery, Gaykhatu ordered arrest of several amirs including his personal keshig Tuladai, Qoncuqbal, Tukal, Bughdai, including Kipchak and put into jail in Tabriz. While his followers Hasan and Taiju demanded their executions, Taghachar advised against it. Baydu on his side, moved to kill Muhammad Sugurchi, governor of Baghdad and arrested governor Baybuqa of Diyar Bakr. Gaykhatu sent his father-in-law Aq Buqa and Taghachar against Baydu on 17 March 1295, himself arriving at Tabriz 4 days later. Little he knew that Taghachar already shifted allegiance to Baydu who left for his encampment at night. While he wanted to flee to Anatolia, his councillors advised to fight against Baydu. Nevertheless, Gaykhatu fled to Mughan. Arriving in Tabriz, Taghachar set Qoncuqbal and Tuladai free, while Gaykhatu desperately begged for mercy. Despite his appeal, he was strangled by a bowstring so as to avoid bloodshed[16] on 21 March 1295. However, some sources put this event on 5 March or 25 April.[4] An alternative story of Gaykhatu's death claims Baydu made war on him because of his introduction of paper money and subsequently killed him in battle.[17]

Personality

Gaykhatu was a noted dissolute who was addicted to wine, women, and sodomy, not necessarily in that order, according to Mirkhond.[17] But he was also known for his secularism and communal harmony. Like other Buddhist kings, he used to liberally give patronage to all religions Among his beneficiaries were the Nestorian Christians, who praise him abundantly for his gifts to the Church, as apparent in the history of Mar Yahballaha III.[18]He was described a just and charitable ruler in Tārikh-i Āl-i Saldjūq.[19]

Family

Gaykhatu had eight consorts from different clans:

- Aisha Khatun, daughter of Toghu Jalair, son of Elgai Noyan

- Ula Qutlugh Khatun - married to Ghurbatai Güregen of Hushin tribe

- El Qutlugh Khatun - married on 7 August 1301 to Qutlughshah Noyan of Manghuds

- Ara Qutlugh Khatun

- Dondi Khatun (d. 9 February 1298), daughter of Aq Buqa Jalayir, son of Elgai Noyan

- Alafrang (d. 30 May 1304) - married to Nani Aghachi after death of Gaykhatu

- Jahan Temür

- A daughter — married to Eljidai Quschi (d. 4 October 1295)

- Iranshah

- Qutlugh Malik Khatun - married firstly to Qurumshi, son of Alinaq, married secondly to Muhammad, son of Chichak and Tödegech Khatun

- Alafrang (d. 30 May 1304) - married to Nani Aghachi after death of Gaykhatu

- Eltuzmish Khatun, daughter of Qutlugh Timur Güregen of Khongirad, widow of Abaqa

- Padishah Khatun (executed 1295), daughter of Qutb-ud-din, ruler of Kerman and Kutlugh Turkan, widow of Abaqa

- Uruk Khatun, daughter of Saricha of Keraites, widow of Arghun Khan

- Bulughan Khatun (m. 1292, died 5 January 1310), daughter of Otman, nephew of Abatai Noyan of Khongirad, and widow of Arghun

- Nani Agachi

- Chin Pulad

- Esan Khatun, daughter of Beglamish, brother of Ujan of Arulat

References

- JAHN, KARL (1970). "PAPER CURRENCY IN IRAN: A contribution to the cultural and economic history of Iran in the Mongol Period". Journal of Asian History. 4 (2): 101–135. ISSN 0021-910X. JSTOR 41929763.

- Hope, Michael (22 September 2016). Power, politics, and tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran. Oxford. pp. 127–132. ISBN 978-0-19-108107-1. OCLC 959277759.

- Lane, George (2018-05-03). The Mongols in Iran: Qutb Al-Din Shirazi's Akhbar-i Moghulan. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-351-38752-1.

- Ekici, Kansu (2012). Ilkhanid ruler Gaykhatu and his era (Thesis) (in Turkish). Isparta: SDÜ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü. OCLC 865111740.

- Kapar, Mehmet Ali. "XIII-XIV. Yüzyıllarda Karamanoğulları-Çukurova Ermenileri İlişkileri" [The Relationship between Karāmān Oghullari-Cilician Armenians in the XIII-XIV. Century]. Selçuk Ün. Sos. Bil. Ens. Der. (in Turkish).

- Atwood, p. 234

- Broadbridge, Anne F. (2018-07-18). Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 282. doi:10.1017/9781108347990.010. ISBN 978-1-108-34799-0.

- Boroujerdi, Mehrzad (2013-05-01). Mirror for the Muslim Prince: Islam and the Theory of Statecraft. Syracuse University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8156-5085-0.

- Kofoğlu, Sait (2009-04-01). "A Principality In Southwest Anatolia In The Post-Selçuk Era: Esrefogullari". Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. 2009 (19): 49–59. ISSN 1300-9435.

- Soudavar, Abolala. (1992). Art of the Persian courts : selections from the Art and History Trust Collection. Beach, Milo Cleveland., Art and History Trust Collection (Houston, Tex.). New York: Rizzoli. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-8478-1660-5. OCLC 26396207.

- "GAYḴĀTŪ KHAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- Lane, George, 1952- (2009). Daily life in the Mongol empire. Indianapolis, Ind.: Hackett Pub. Co. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-87220-968-8. OCLC 262429326.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Al-Maqrizi, p. 242, vol. 2.

- Ashtor 1976, p. 257.

- L. J. Ward, “The Ẓafar-nāmah of Ḥamd Allāh Mustaufi and the Il-Khān dynasty of Iran,” Ph.D. diss, 3 vols., University of Manchester, 1983, pp. 354-355

- Steppes, p. 377.

- "The history of Persia. Containing, the lives and memorable action of its kings from the first erecting of that monarchy to this time; an exact description of all its dominions; a curious account of India, China, Tartary, Kermou, Arabia, Nixabur, and the islands of Ceylon and Timor; as also of all cities occasionally mention'd, as Schiras, Samarkand, Bokara, &c. Manners and customs of those people, Persian worshippers of fire; plants, beasts, product, and trade .. To which is added, an abridgment of the lives of the kings of Harmuz, or Ormuz. The Persian history written in Arabick, by Mirkoud, a famous Eastern author; that of Ormuz, by Torunxa, king of that island, both of them tr. into Spanish, by Antony Teixeira, who liv'd several years in Persia and India; and now render'd into English". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- Luisetto, p. 146.

- Woods, John E.; Tucker, Ernest (2006). History and Historiography of Post-Mongol Central Asia and the Middle East: Studies in Honor of John E. Woods. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 153. ISBN 978-3-447-05278-8.

Sources

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- René Grousset, Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, 1939

- Luisetto, Frédéric, "Arméniens et autres Chrétiens d'Orient sous la domination Mongole", Geuthner, 2007, ISBN 978-2-7053-3791-9