Frodo Baggins

Frodo Baggins is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, and one of the protagonists in The Lord of the Rings. Frodo is a hobbit of the Shire who inherits the One Ring from his cousin Bilbo Baggins and undertakes the quest to destroy it in the fires of Mount Doom in Mordor. He is mentioned in Tolkien's posthumously published works, The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales.

| Frodo Baggins | |

|---|---|

| First appearance | The Fellowship of the Ring (1954) |

| Last appearance | Bilbo's Last Song (1974) |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | Mr. Underhill |

| Race | Hobbit |

| Affiliation | Company of the Ring |

| Family | Bilbo Baggins (cousin) |

| Home | The Shire |

Frodo is repeatedly wounded during the quest, and becomes increasingly burdened by the Ring as it nears Mordor. He changes, too, growing in understanding and compassion, and avoiding violence.

Frodo's name comes from the Old English name Fróda, meaning "wise by experience". Commentators have written that he combines courage, selflessness, and fidelity, and that as a good character, he seems unexciting but grows through his quest, an unheroic person who reaches heroic stature.

Internal history

Background

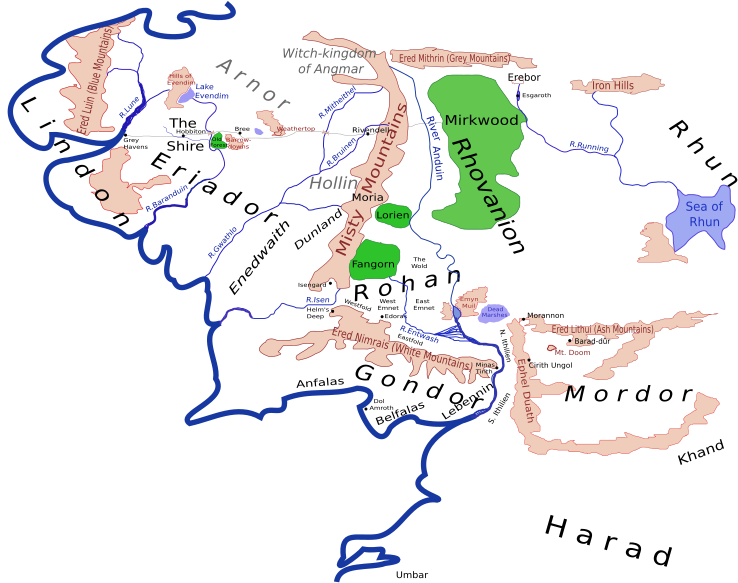

Frodo is introduced in The Lord of the Rings as Bilbo Baggins's relative and adoptive heir.[T 1] In The Hobbit, Bilbo had been taken by the Wizard Gandalf and a party of Dwarves from his safe home, Bag End, in the Shire across the Misty Mountains and the dark forest of Mirkwood to recapture the Dwarves' ancient home and treasure under the Lonely Mountain. The treasure had been guarded by a dragon, Smaug. Through many adventures, Smaug had been killed and Bilbo had returned home with a substantial portion of the treasure. He lived the life of a rich eccentric for many years.[1] Frodo's parents Drogo Baggins and Primula Brandybuck had been killed in a boating accident when Frodo was 12; Frodo spent the next nine years living with his maternal family, the Brandybucks in Brandy Hall. At the age of 21 he was adopted by Bilbo, his cousin,[lower-alpha 1] who brought him to live at Bag End. He and Bilbo shared the same birthday, the 22nd of 'September'. Bilbo introduced Frodo to the Elvish languages, and they often went on long walking trips together.[T 1]

The Fellowship of the Ring

Frodo comes of age as Bilbo leaves the Shire for good on his one hundred and eleventh birthday. Frodo inherits Bag End and Bilbo's ring. Gandalf, at this time, is not certain about the origin of the ring, so he warns Frodo to avoid using it and to keep it secret.[T 1] Frodo keeps the Ring hidden for the next 17 years, and the Ring gives him the same longevity it gave Bilbo. Gandalf returns to prove to him that it is the One Ring of the Dark Lord Sauron, who seeks to recover and use it to conquer Middle-earth.[T 2]

Realizing that he is a danger to the Shire as long as he remains there with the Ring, Frodo decides to take it to Rivendell, home of Elrond, a mighty Elf-lord. He leaves with three companions: his gardener Samwise Gamgee and his cousins Merry Brandybuck and Pippin Took. They escape just in time, for Sauron's most powerful servants, the Nine Nazgûl, have entered the Shire as Black Riders, looking for Bilbo and the Ring. They follow Frodo's trail across the Shire and nearly intercept him.[T 3][T 4][T 5]

The hobbits escape the Black Riders by travelling through the Old Forest. They are waylaid by the magic of Old Man Willow, but rescued by Tom Bombadil,[T 6] who gives them shelter and guides them on their way.[T 7] They are caught in fog on the Barrow Downs by a barrow-wight and are entranced under a spell. Frodo breaks loose from the spell, attacks the barrow-wight and summons Bombadil, who again rescues the hobbits and sets them on their way.[T 8]

At the Prancing Pony inn in the village of Bree, Frodo receives a delayed letter from Gandalf, and meets a man who calls himself Strider, a Ranger of the North; his real name is Aragorn. The One Ring slips onto Frodo's finger inadvertently in the inn's common room, turning Frodo invisible. This attracts the attention of Sauron's agents, who ransack the hobbits' rooms in the night.[T 9] The group, under Strider's guidance, flees through the marshes.[T 10]

While encamped on Weathertop hill, they are attacked by five Nazgûl. The chief of the Nazgûl stabs Frodo with a Morgul-blade; Aragorn routs them with fire. A piece of the blade remains in Frodo's shoulder and, working its way towards his heart, threatens to turn him into a wraith under control of the Nazgul.[T 11] With the help of his companions and an Elf-lord, Glorfindel, Frodo is able to evade the Nazgûl and reach Rivendell.[T 12] Nearly overcome by his wound, he is healed over time by Elrond.[T 13]

The Council of Elrond meets in Rivendell and resolves to destroy the Ring by casting it into Mount Doom in Mordor, the realm of Sauron. Frodo, realizing that he is destined for this task, steps forward to be the Ring-bearer. A Fellowship of nine companions is formed to guide and protect him: the hobbits, Gandalf, Aragorn, the dwarf Gimli, the elf Legolas, and Boromir, a man of Gondor. Together they set out from Rivendell. Frodo is armed with Sting, Bilbo's Elvish knife; he wears Bilbo's coat of Dwarf mail made of mithril.[T 14] The company, seeking a way through the Misty Mountains, tries the Pass of Caradhras, but abandons it in favour of the mines of Moria.[T 15] In Moria Frodo is stabbed by an Orc-spear, but his coat of mithril armour saves his life.[T 16] They are led through the mines by Gandalf, until he is killed battling a Balrog.[T 17] Aragorn leads them out to Lothlórien.[T 18] There Galadriel gives Frodo an Elven cloak and a phial carrying the Light of Eärendil to aid him on his dangerous quest.[T 19]

The Fellowship travel by boat down the Anduin River and reach the lawn of Parth Galen, just above the impassable falls of Rauros.[T 20] There, Boromir, succumbing to the lure of the Ring, tries to take the ring by force from Frodo. Frodo escapes by putting on the Ring and becoming invisible. This breaks the Fellowship; the company is scattered by invading Orcs. Frodo chooses to continue the quest alone, but Sam follows his master, joining him on the journey to Mordor.[T 21]

The Two Towers

Frodo and Sam make their way through the wilds, followed by the creature Gollum, who has been tracking the Fellowship since Moria, seeking to reclaim the Ring. Gollum attacks the hobbits, but Frodo subdues him with Sting. He takes pity on Gollum and spares his life, binding him to a promise to guide them through the dead marshes to the Black Gate, which Gollum does.[T 22][T 23] They find the gate impassable, but Gollum says that there is "another way" into Mordor,[T 24] and Frodo, over Sam's objections, allows him to lead them south into Ithilien.[T 25] There they meet Faramir, younger brother of Boromir, who takes them to a hidden cave, Henneth Annûn.[T 26] Frodo allows Gollum to be captured by Faramir, saving Gollum's life but leaving him feeling betrayed by his "master". Faramir provisions the hobbits and allows them to go on their way, but warns Frodo to beware of Gollum's treachery.[T 27][T 28]

The three of them pass near Minas Morgul, where the pull of the Ring becomes almost unbearable. There they began the long climb up the Endless Stair of Cirith Ungol,[T 29] and at the top enter a tunnel, not knowing it is the home of the giant spider Shelob. Gollum hopes to deliver the hobbits to her and retake the Ring after she has killed them. Shelob stings Frodo, rendering him unconscious, but Sam drives her off with Sting and the Phial of Galadriel.[T 30] After attempting unsuccessfully to wake Frodo up, and unable to find any signs of life, Sam concludes that Frodo is dead and decides that his only option is to take the Ring and continue the quest. But he overhears orcs who find Frodo's body and learns that Frodo is not dead. The orcs take Frodo for questioning; Sam tries to follow but finds the door locked against him.[T 31]

The Return of the King

Sam rescues Frodo from the Orcs. After a brief confrontation in which Frodo becomes enraged that Sam has taken the Ring, Sam restores the Ring to Frodo.[T 32] The two of them, dressed in scavenged Orc-armour, set off for Mount Doom, trailed by Gollum.[T 33] They witness the plains of Mordor empty at the approach of the Armies of the West. As the Ring gets closer to its master, Frodo becomes progressively weaker as its influence grows. When they run out of water, they leave all unnecessary baggage behind to travel light. As they reach Mount Doom, Gollum reappears and attacks Frodo, who beats him back. While Sam fights with Gollum, Frodo enters the chasm in the volcano where Sauron forged the Ring. Here Frodo loses the will to destroy the Ring, and instead puts it on, claiming it for himself. Gollum pushes Sam aside and attacks the invisible Frodo, biting off his finger. As he dances around in elation, Gollum loses his balance and falls with the Ring into the fiery Cracks of Doom. The Ring is destroyed, and with it Sauron's power. Frodo and Sam are rescued by Gandalf and several Great Eagles as Mount Doom erupts.[T 34]

After reuniting with the Fellowship and attending Aragorn's coronation as King of Gondor, the four hobbits return to the Shire.[T 35] They find the entire Shire in a state of upheaval. Saruman's agents—both Hobbits and Men—have taken it over and started a destructive process of industrialization. Saruman governs the Shire in secret under the name of Sharkey until Frodo and his companions lead a rebellion and defeat the intruders. Even after Saruman attempts to stab Frodo, Frodo lets him go.[T 36] Frodo and his companions restore the Shire to its prior state of peace and goodwill. Frodo never completely recovers from the physical, emotional, and psychological wounds he suffered during the quest to destroy the ring. Two years after the Ring was destroyed, Frodo and Bilbo as Ring-bearers are granted passage to Valinor, the earthly paradise where Frodo might find peace.[T 37]

Other works

"The Sea-Bell" was published in Tolkien's 1962 collection of verse The Adventures of Tom Bombadil with the sub-title Frodos Dreme. Tolkien suggests that this enigmatic narrative poem represents the despairing dreams that visited Frodo in the Shire in the years following the destruction of the Ring. It relates the unnamed speaker's journey to a mysterious land across the sea, where he tries but fails to make contact with the people who dwell there. He descends into despair and near-madness, eventually returning to his own country, to find himself utterly alienated from those he once knew.[2]

"Frodo the halfling" is mentioned briefly at the end of The Silmarillion, as "alone with his servant he passed through peril and darkness" and "cast the Great Ring of Power" into the fire.[T 38]

In the poem Bilbo's Last Song, Frodo is at the Grey Havens at the farthest west of Middle-earth, about to leave the mortal world on an elven-ship to Valinor.[3]

"The Hunt for the Ring" in Unfinished Tales describes how the Black Riders travelled to Isengard and the Shire in search of the One Ring, purportedly "according to the account that Gandalf gave to Frodo".[lower-alpha 2] It is one of several mentions of Frodo in the book.[T 39]

Family tree

The Tolkien scholar Jason Fisher notes that Tolkien stated that hobbits were extremely "clannish" and had a strong "predilections for genealogy".[4] Accordingly, Tolkien's decision to include Frodo's family tree in Lord of the Rings gives the book, in Fisher's view, a strongly "hobbitish perspective".[4] The tree also, he notes, serves to show Frodo's and Bilbo's connections and familial characteristics.[4] Frodo's family tree is as follows:[T 40]

| Baggins family tree[T 41] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Concept and creation

Frodo did not appear until the third draft of A Long-Expected Party (the first chapter of The Lord of the Rings), when he was named Bingo, son of Bilbo Baggins and Primula Brandybuck.[T 42] In the fourth draft, he was renamed Bingo Bolger-Baggins, son of Rollo Bolger and Primula Brandybuck.[T 43] Tolkien did not change the name to Frodo until the third phase of writing, when much of the narrative, as far as the hobbits' arrival in Rivendell, had already taken shape.[T 44] Prior to this, the name "Frodo" had been used for the character who eventually became Pippin Took.[T 45] In drafts of the final chapters, published as Sauron Defeated, Gandalf names Frodo Bronwe athan Harthad ("Endurance Beyond Hope"), after the destruction of the Ring. Tolkien states that Frodo's name in Westron was Maura Labingi.[T 46]

Interpretations

Name and origins

Frodo is the only prominent hobbit whose name is not explained in Tolkien's Appendices to The Lord of the Rings. In a letter Tolkien states that it is the Old English name Fróda, connected to fród, "wise by experience".[T 47] The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey suggests that the choice of name is significant: not, in Tolkien's phrase, one of the many "names that had no meaning at all in [the hobbits'] daily language". Instead, he notes, the Old Norse name Fróði is mentioned in Beowulf as the minor character Fróda. Fróði was, he writes, said by Saxo Grammaticus and Snorri Sturluson to be a peaceful ruler at the time of Christ, his time being named the Fróða-frið, the peace of Fróði. This was created by his magic mill, worked by two female giants, that could churn out peace and gold. He makes the giants work all day long at this task, until they rebel and grind out an army instead, which kills him and takes over, making the giants grind salt until the sea is full of it. The name Fróði is forgotten. Clearly, Shippey observes, evil is impossible to cure; and Frodo too is a "peacemaker, indeed in the end a pacifist". And, he writes, as Frodo gains experience through the quest, he also gains wisdom, matching the meaning of his name.[5]

Character

Michael Stanton, writing in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, describes Frodo's character as combining "courage, selflessness, and fidelity",[6] attributes that make Frodo ideal as a Ring-bearer. He lacks Sam's simple sturdiness, Merry and Pippin's clowning, and the psychopathology of Gollum, writes Stanton, bearing out the saying that good is less exciting than evil; but Frodo grows through his quest, becoming "ennobled" by it, to the extent that returning to the Shire feels in Frodo's words "like falling asleep again".[6]

Christ figure

Christian commentators have stated that there is no one complete, concrete, visible Christ figure in The Lord of the Rings, but that Frodo serves as the priestly aspect of Christ, alongside Gandalf as prophet and Aragorn as King, together making up the threefold office of the Messiah.[7][8][9][10]

Tragic hero

The Tolkien scholar Jane Chance quotes Randel Helms's view that in both The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, "a most unheroic hobbit [Bilbo, Frodo] achieves heroic stature" in a quest romance.[11] Chance writes that Frodo grows from seeing the threat as external, such as from the Black Riders, to internal, whether within the Fellowship, as shown by Boromir's attempt on the Ring, or within himself, as he struggles against the controlling power of the Ring.[12]

The Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger summarizes Frodo's role in Lord of the Rings: "The greatest hero of all, Frodo Baggins, is also the most tragic. He comes to the end of his story bereft of the Ring, denied in his home Shire the recognition he deserves, and unable to continue his life as it was before his terrible adventure."[13]

Providence

The Tolkien critic Paul H. Kocher discusses the role of providence, in the form of the intentions of the angel-like Valar or of the creator Eru Ilúvatar, in Bilbo's finding of the Ring and Frodo's bearing of it; as Gandalf says, Frodo was "meant" to have it, though it remains his choice to co-operate with this purpose.[14]

Adaptations

Frodo appears in adaptations of The Lord of the Rings for radio, cinema, and stage. In Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated version, Frodo was voiced by Christopher Guard.[15] In the 1980 Rankin/Bass animated version of The Return of the King, made for television, the character was voiced by Orson Bean, who had previously played Bilbo in the same company's adaptation of The Hobbit.[16] In the "massive"[17] 1981 BBC radio serial of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo is played by Ian Holm, who later played Bilbo in Peter Jackson's film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings.[18] In the 1993 television miniseries Hobitit by Finnish broadcaster Yle, Frodo is played by Taneli Mäkelä.[19]

In The Lord of the Rings film trilogy (2001–2003) directed by Peter Jackson, Frodo is played by American actor Elijah Wood. Dan Timmons writes in the Mythopoeic Society's Tolkien on Film: Essays on Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings (Mythopoeic Press, 2005) that the themes and internal logic of the Jackson films are undermined by the portrayal of Frodo, whom he considers a weakening of Tolkien's original.[20] The film critic Roger Ebert writes that he missed the depth of characterisation he felt in the book, Frodo doing little but watching other characters decide his fate "and occasionally gazing significantly upon the Ring".[21] Elijah Wood reprised his role of Frodo in a brief appearance in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey.[22]

On stage, Frodo was portrayed by James Loye in the three-hour stage production of The Lord of the Rings, which opened in Toronto in 2006, and was brought to London in 2007.[23][24] Frodo was portrayed by Joe Sofranko in the Cincinnati productions of The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003) for Clear Stage Cincinnati.[25][26][27]

See also

Notes

- Although Frodo referred to Bilbo as his "uncle", they were in fact first and second cousins, once removed either way (his paternal great-great-uncle's son's son and his maternal great-aunt's son).

- In the fiction, the account survives as Frodo wrote it in the Red Book of Westmarch.

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 1, "A Long-Expected Party"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 2, "The Shadow of the Past"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 3, "Three is Company"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 4, "A Short Cut to Mushrooms"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 5, "A Conspiracy Unmasked"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 6, "The Old Forest"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 7, "In the House of Tom Bombadil"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 8, "Fog on the Barrow-Downs"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 9, "At the Sign of the Prancing Pony"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 10, "Strider"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 11, "A Knife in the Dark"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 1, ch. 12, "Flight to the Ford"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 1, "Many Meetings"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 2, "The Council of Elrond"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 3, "The Ring Goes South"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 4, "A Journey in the Dark"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 5, "The Bridge of Khazad-Dum"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 6, "Lothlórien"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 8, "Farewell to Lórien"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 9, "The Great River"

- The Fellowship of the Ring book 2, ch. 10, "The Breaking of the Fellowship"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 1, "The Taming of Sméagol"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 2, "The Passage of the Marshes"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 3, "The Black Gate is Closed"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 4, "Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 5, "The Window on the West"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 5, "The Forbidden Pool"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 7, "Journey to the Cross-Roads"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 8, "The Stairs of Cirith Ungol"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 9, "Shelob's Lair"

- The Two Towers book 4, ch. 10, "The Choices of Master Samwise"

- The Return of the King book 6, ch. 1, "The Tower of Cirith Ungol"

- The Return of the King book 6, ch. 2, "The Land of Shadow"

- The Return of the King book 6, ch. 3, "Mount Doom"

- The Return of the King book 6, ch. 7, "Homeward Bound"

- The Return of the King, book 6, ch. 8, "The Scouring of the Shire"

- The Return of the King book 6, ch. 9, "The Grey Havens"

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- Unfinished Tales, part 3, ch. 4 "The Hunt for the Ring"

- Return of the King, Appendix C, "Family Trees", "Baggins of Hobbiton"

- J. R. R. Tolkien. The Return of the King, Appendix C, "Family Trees"

- The Return of the Shadow, pp. 28–29.

- The Return of the Shadow, pp. 36–37.

- The Return of the Shadow, p. 309.

- The Return of the Shadow, p. 267.

- The Peoples of Middle-earth, "The Appendix on Languages"

- Letters, #168 to Richard Jeffrey, 7 September 1955

Secondary

- Stanton, Michael N. (2013) [2007]. "Bilbo Baggins". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2001). A Question of Time: J.R.R. Tolkien's Road to Faërie. Kent State University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-87338-699-9.

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2017). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion. 2 (Second ed.). HarperCollins. p. 158.

- Fisher, Jason (2007). "Family Trees". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. pp. 231–237. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Stanton, Michael N. (2013) [2007]. "Frodo". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 223–225. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Kreeft, Peter J. (November 2005). "The Presence of Christ in The Lord of the Rings". Ignatius Insight.

- Kerry, Paul E. (2010). Kerry, Paul E. (ed.). The Ring and the Cross: Christianity and the Lord of the Rings. Fairleigh Dickinson. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-1-61147-065-9.

- Schultz, Forrest W. (1 December 2002). "Christian Typologies in The Lord of the Rings". Chalcedon. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Pearce, Joseph (2013) [2007]. "Christ". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Helms, Randel (1974). Tolkien's World. Houghton Mifflin. p. 21.

- Nitzsche, Jane Chance (1980) [1979]. Tolkien's Art. Papermac. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0-333-29034-8.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2008). Harold Bloom (ed.). An Unfinished Symphony (PDF). J. R. R. Tolkien. Bloom's Modern Critical Views. Bloom's Literary Criticism, an imprint of Infobase Publishing. pp. 121–127. ISBN 978-1-60413-146-8.

- Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-Earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. p. 37. ISBN 0140038779.

- "Actor and musician Christopher Guard appoints Palamedes PR". SWNS. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

He is perhaps best-known for voicing Frodo Baggins in the animated version of The Lord of the Rings

- Hoffman, Jordan (8 February 2020). "Orson Bean, Legendary Character Actor, Killed in Accident at 91". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Obituary: Ian Holm". BBC. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

he took the part of Frodo Baggins in BBC Radio 4's massive adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, which featured Holm alongside a host of other stars including Michael Hordern and Robert Stephens.

- "The Tolkien Library review of the Lord of the Rings Radio Adaptation". Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Kajava, Jukka (29 March 1993). "Tolkienin taruista on tehty tv-sarja: Hobitien ilme syntyi jo Ryhmäteatterin Suomenlinnan tulkinnassa" [Tolkien's tales have been turned into a TV series: The Hobbits have been brought to live in the Ryhmäteatteri theatre]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). (subscription required)

- Timmons, Dan (2005). "Frodo on Film: Peter Jackson's Problematic Portrayal". In Croft, Janet Brennan (ed.). Tolkien on Film: Essays on Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings. Altadena: Mythopoeic Press. ISBN 978-1-887726-09-2. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- Ebert, Roger (18 December 2002). "Reviews Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers". Roger Ebert. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "New Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey Pics: Elijah Wood Returns as Frodo; Martin Freeman's Bilbo Gets His Sword". Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- "Brent Carver, James Loye, Matthew Warcus, 'Rings'". www.hellomagazine.com. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ""LOTR" In London". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Lifeline wraps up Tolkien trilogy in jaunty style". Chicago Tribune. 18 October 2001.

- "J.R.R. Tolkien's The Return of the King". Clear Stage Cincinnati. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- Hetrick, Adam (11 November 2013). "Lord of the Rings Musical Will Embark On 2015 World Tour". Playbill. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Two Towers, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08256-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-29917-9

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Return of the Shadow, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-49863-5

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Peoples of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-82760-4

.jpg)