French cruiser Friant

Friant was a protected cruiser of the French Navy built in the 1890s, and the lead ship of the Friant class. Friant and her two sister ships were ordered as part of a major construction program directed against France's Italian and German opponents in the Triple Alliance, and they were intended to serve with the main fleet, and overseas in the French colonial empire. They were armed with a main battery of six 164 mm (6.5 in) guns and had a top speed of 18.7 knots (34.6 km/h; 21.5 mph).

Friant | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Friant |

| Builder: | Arsenal de Brest |

| Laid down: | 1891 |

| Launched: | 17 April 1893 |

| Completed: | April 1895 |

| Stricken: | 1920 |

| Status: | Broken up |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 3,982 long tons (4,046 t) |

| Length: | 94 m (308 ft 5 in) pp |

| Beam: | 12.98 m (42 ft 7 in) |

| Draft: | 6.30 m (20 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 18.7 knots (34.6 km/h; 21.5 mph) |

| Range: | 6,000 nmi (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 339 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Friant spent her first years in service assigned to the Northern Squadron, based in the English Channel. There, she was primarily occupied with training exercises. She was deployed to East Asia by early 1901 in response to the Boxer Uprising, and she remained in the region after the conflict ended. After returning to France, she received new boilers and thereafter returned to fleet operations.

At the start of World War I in August 1914, Friant had been on station in France's colonies in the Americas. She was initially assigned to a cruiser squadron to patrol the western end of the English Channel. In September, she was moved to French Morocco to join a group of cruisers patrolling for German commerce raiders. The ship was later moved to the Gulf of Guinea to patrol Germany's former colonies in western Africa. She ended the war having been converted into a repair ship based in Morocco and later at Mudros to support a flotilla of submarines. She was struck from the naval register in 1920 and sold to ship breakers.

Design

In response to a war scare with Italy in the late 1880s, the French Navy embarked on a major construction program in 1890 to counter the threat of the Italian fleet and that of Italy's ally Germany. The plan called for a total of seventy cruisers for use in home waters and overseas in the French colonial empire. The Friant class—Friant, Bugeaud and Chasseloup-Laubat—was the first group of protected cruisers to be authorized under the program.[1][2]

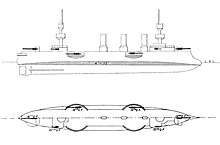

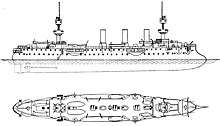

Friant was 94 m (308 ft 5 in) long between perpendiculars, with a beam of 12.98 m (42 ft 7 in) and a draft of 6.30 m (20 ft 8 in). She displaced 3,982 long tons (4,046 t). Her crew consisted of 339 officers and enlisted men. The ship's propulsion system consisted of a pair of triple-expansion steam engines driving two screw propellers. Steam was provided by twenty coal-burning Niclausse-type water-tube boilers that were ducted into three funnels. Her machinery was rated to produce 9,500 indicated horsepower (7,100 kW) for a top speed of 18.7 knots (34.6 km/h; 21.5 mph).[3] She had a cruising range of 6,000 nautical miles (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4]

The ship was armed with a main battery of six 164 mm (6.5 in) 45-caliber guns. They were placed in individual pivot mounts; one was on the forecastle, two were in sponsons abreast the conning tower, and the last was on the stern. These were supported by a secondary battery of four 100 mm (3.9 in) guns, which were carried in pivot mounts in the conning towers, one on each side per tower. For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she carried four 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and eleven 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder guns. She was also armed with two 350 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes in her hull above the waterline. Armor protection consisted of a curved armor deck that was 30 to 80 mm (1.2 to 3.1 in) thick, along with 75 mm (3 in) plating on the conning tower.[3]

Service history

Construction of Friant began with her keel laying at the Arsenal de Brest in 1891.[3] She was launched on 17 April 1893, the same day as her sister ship Chasseloup-Laubat,[5] but stability problems delayed Friant's completion. Her original, heavy military masts were removed, along with her four 47 mm guns to reduce weight high in the ship.[6] She was completed in April 1895,[3] and completed her sea trials later that year,[7] in time to take part in the annual fleet maneuvers that began on 1 July. The exercises took place in two phases, the first being a simulated amphibious assault in Quiberon Bay, and the second revolving around a blockade of Rochefort and Cherbourg. The maneuvers concluded on the afternoon of 23 July.[8]

In 1896, she was assigned to the Northern Squadron, based in the English Channel. The unit was France's secondary battle fleet, and at that time also included the ironclad Hoche; four coastal defense ships; the armored cruiser Dupuy de Lôme; and the protected cruisers Chasseloup-Laubat and Coëtlogon.[9] She took part in training maneuvers with the rest of the squadron that year, which were conducted from 6 to 26 July in conjunction with the local defense forces of Brest, Rochefort]], Cherbourg, and [[Lorient. The squadron was divided into three divisions for the maneuvers, and Friant was assigned to the 1st Division along with the ironclad Hoche, the coastal defense ship Amiral-Tréhouart, and the aviso Lance, which represented part of the defending French squadron.[10]

By 1897, the cruiser force of the squadron was revised to include Friant, Dupuy de Lôme, the armored cruiser Bruix, and the unprotected cruiser Epervier.[11] Friant was mobilized in 1897 to participate in the large-scale maneuvers of 1897 with the Northern Squadron, which were held in July. Suchet and the bulk of the squadron were tasked with intercepting the coastal defense ship Bouvines, which was to steam from Cherbourg to Brest between 15 and 16 July. As with the previous year's maneuvers, the defending squadron was unable to intercept Bouvines before she reached Brest. The squadron then moved to Quiberon Bay for another round of maneuvers from 18 to 21 July. This scenario saw the protected cruisers Sfax and Tage simulate a hostile fleet steaming from the Mediterranean Sea to attack France's Atlantic coast. Unlike the previous exercises, Friant and the rest of the Northern Squadron successfully intercepted the cruisers and "defeated" them.[12] The unit remained largely unchanged in 1898, apart from the substitution of Pothuau for Bruix and Surcouf for Epervier.[13] Later that year, Friant was transferred to the training squadron, along with the armored cruiser Amiral Charner and the protected cruiser Davout.

Friant and both of her sister ships had been deployed to East Asia by January 1901 as part of the response to the Boxer Rebellion in Qing China; at that time, six other cruisers were assigned to the station in addition to the three Friant-class ships.[15][lower-alpha 1] She remained in East Asian waters in 1902.[16] Friant was struck by a typhoon on 8 August 1902 while moored in Nagasaki, Japan.[17] In the mid-1900s, after returning to France, Friant was reboilered with newer models; the work was completed in 1907, and after conducting sea trials she returned to service with the fleet.[18]

World War I

At the start of World War I in August 1914, Friant was assigned to the Division de l'Atlantique (Division of the Atlantic), along with the armored cruiser Condé and the protected cruiser Descartes.[19] Friant was in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, in late July when war became imminent and the French naval command recalled her to rejoin the fleet.[20] Upon arriving back in France, she was assigned to the 2nd Light Squadron, which at that time consisted of the armored cruisers Marseillaise, Amiral Aube, Jeanne d'Arc, Gloire, Gueydon, and Dupetit-Thouars. The unit was based in Brest, and along with Lavoisier, the squadron was strengthened by the addition of several other cruisers over the following days, including the armored cruisers Kléber and Desaix, the protected cruisers Châteaurenault, D'Estrées, Lavoisier, and Guichen, and several auxiliary cruisers. The ships then conducted a series of patrols in the English Channel in conjunction with a force of four British cruisers.[21]

Over the course of 1914 and 1915, the cruisers of the squadron were dispersed to other stations,[21] and Friant was moved to French Morocco by September 1914, where she joined the armored cruisers Bruix and Amiral Charner and the protected cruisers Cosmao and Cassard in the Division du Maroc (Morocco Division). The cruisers patrolled for German arms shipments to Spain and Spanish Morocco. The division tasked with patrolling the sea lanes off the coast of northwestern Africa and protecting merchant shipping from commerce raiders. It was also responsible for escorting convoys and patrolling anchorages in the Canary Islands to ensure German U-boats were not using them to refuel. The cruisers operated out of Oran, French Morocco. By late September, it had become clear that German raiders were not operating in the area, so the armored cruisers were transferred elsewhere.[22][23]

After French and British forces conquered Germany's colonies in western Africa, including Togoland, Kamerun, and German Southwest Africa, the French stationed Friant in the Gulf of Guinea, though she was later replaced by the cruiser Surcouf.[22] She was later converted into a repair ship based in Morocco. She remained there until 1918, when she was moved to Mudros in the Aegean Sea to support the 3rd Submarine Flotilla. By that time, she had been reduced to a single funnel. She was struck from the naval register in 1920 and thereafter broken up.[3][5]

Footnotes

Notes

- The Far East and Western Pacific Division consisted of the flagship, D'Entrecasteaux, the armored cruiser Amiral Charner, and seven protected cruisers: Friant, Descartes, Pascal, Bugeaud, Chasseloup-Laubat, Jean Bart, and Guichen. It also included a number of local guard ships and gunboats for local defense.[15]

Citations

- Ropp, pp. 195–197.

- Gardiner, pp. 310–311.

- Gardiner, p. 311.

- Garbett 1904, p. 563.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 193.

- Brassey 1895, p. 23.

- Brassey 1895, p. 27.

- Barry, pp. 186–190.

- Brassey 1896, p. 62.

- Thursfield 1897, p. 167.

- Brassey 1897, p. 57.

- Thursfield 1898, pp. 140–143.

- Brassey 1898, p. 57.

- Jordan & Caresse 2017, p. 218.

- Brassey 1902, p. 51.

- Algue, pp. 552–553.

- Garbett 1907, p. 1538.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 219.

- Corbett, p. 48.

- Meirat, p. 22.

- Jordan & Caresse 2019, p. 227.

- Corbett, p. 275.

References

- Algue, Jose (1904). "The Barocyclonometer". Report of the Director of the Philippine Weather Bureau. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing: 533–554. OCLC 37664704.

- Barry, E. B. (July 1896). "Naval Manoeuvres of 1895". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. XV: 163–214. OCLC 727366607.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895). "Ships Building In France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 19–28. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1896). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–71. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1897). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 56–77. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1898). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 56–66. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1902). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 47–55. OCLC 496786828.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1920). Naval Operations: To the Battle of the Falklands, December 1914. I. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 174823980.

- Garbett, H., ed. (May 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (315): 560–566. OCLC 1077860366.

- Garbett, H., ed. (1907). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. LI: 47–55. OCLC 1077860366.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4118-9.

- Meirat, Jean (1975). "Details and Operational History of the Third-Class Cruiser Lavoisier". F. P. D. S. Newsletter. Akron: Foreign Periodicals Data Service. III (3): 20–23. OCLC 41554533.

- "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLII (247): 1091–1094. September 1898. OCLC 1077860366.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1897). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Naval Manœuvres in 1896". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 140–188. OCLC 496786828.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1898). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "II: French Naval Manœuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 138–143. OCLC 496786828.