French cruiser Chasseloup-Laubat

Chasseloup-Laubat was a protected cruiser of the Friant class built in the 1890s for the French Navy, the last of three ships of the class. The Friant-class cruisers were ordered as part of a construction program directed at strengthening the fleet's cruiser force. At the time, France was concerned with the growing naval threat of the Italian and German fleets, and the new cruisers were intended to serve with the main fleet, and overseas in the French colonial empire. Chasseloup-Laubat and her two sister ships were armed with a main battery of six 164 mm (6.5 in) guns, were protected by an armor deck that was 30 to 80 mm (1.2 to 3.1 in) thick, and were capable of steaming at a top speed of 18.7 knots (34.6 km/h; 21.5 mph).

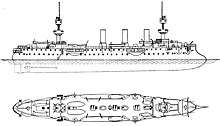

Chasseloup-Laubat during a visit to the United States in 1907 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Chasseloup-Laubat |

| Builder: | Arsenal de Cherbourg |

| Laid down: | June 1891 |

| Launched: | 17 April 1893 |

| Completed: | 1895 |

| Stricken: | 1911 |

| Fate: | Abandoned in Nouadhibou Bay |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 3,824 long tons (3,885 t) |

| Length: | 94 m (308 ft 5 in) pp |

| Beam: | 12.98 m (42 ft 7 in) |

| Draft: | 6.30 m (20 ft 8 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 18.7 knots (34.6 km/h; 21.5 mph) |

| Range: | 6,000 nmi (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 339 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Chasseloup-Laubat spent her early career in the Northern Squadron, which was based in the English Channel. During this period, her time was primarily occupied conducting training exercises. She was sent to East Asia in response to the Boxer Uprising in Qing China by 1901, and she remained there through 1902. Chasseloup-Laubat had returned to France at some point before 1907, and she participated in a visit to the United States that year for the Jamestown Exposition. She served with the Northern Squadron in 1908, was hulked in 1911, and disarmed in 1913. After the start of World War I in 1914, Chasseloup-Laubat was converted into a distilling ship to support the main French fleet at Corfu. She was eventually sunk in 1926 in the bay of Nouadhibou, Mauritania.

Design

In response to a war scare with Italy in the late 1880s, the French Navy embarked on a major construction program in 1890 to counter the threat of the Italian fleet and that of Italy's ally Germany. The plan called for a total of seventy cruisers for use in home waters and overseas in the French colonial empire. The Friant class was the first group of protected cruisers to be authorized under the program.[1][2]

Chasseloup-Laubat was 94 m (308 ft 5 in) long between perpendiculars, with a beam of 12.98 m (42 ft 7 in) and a draft of 6.30 m (20 ft 8 in). She displaced 3,824 long tons (3,885 t). Her crew consisted of 339 officers and enlisted men. The ship's propulsion system consisted of a pair of triple-expansion steam engines driving two screw propellers. Steam was provided by twenty coal-burning Lagrafel d'Allest water-tube boilers that were ducted into three funnels. Her machinery was rated to produce 9,500 indicated horsepower (7,100 kW) for a top speed of 18.7 knots (34.6 km/h; 21.5 mph).[3] She had a cruising range of 6,000 nautical miles (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4]

The ship was armed with a main battery of six 164 mm (6.5 in) 45-caliber guns. They were placed in individual pivot mounts; one was on the forecastle, two were in sponsons abreast the conning tower, and the last was on the stern. These were supported by a secondary battery of four 100 mm (3.9 in) guns, which were carried in pivot mounts in the conning towers, one on each side per tower. For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she carried four 47 mm (1.9 in) 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and eleven 37 mm (1.5 in) 1-pounder guns. She was also armed with two 350 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes in her hull above the waterline. Armor protection consisted of a curved armor deck that was 30 to 80 mm (1.2 to 3.1 in) thick, along with 75 mm (3 in) plating on the conning tower.[3]

Service history

Chasseloup-Laubat was built in Cherbourg, beginning with her keel laying at the Arsenal de Cherbourg in June 1891. She was launched on 17 April 1893, the same day as her sister ship Friant, and was completed in 1895.[3][5] She conducted her sea trials later that year.[6] At some point early in her career, she was fitted with bilge keels to improve her stability.[7] The ship was ready in time to participate in the annual fleet maneuvers with the Northern Squadron that began on 1 July 1895. The exercises took place in two phases, the first being a simulated amphibious assault in Quiberon Bay, and the second revolving around a blockade of Rochefort and Cherbourg. The maneuvers concluded on the afternoon of 23 July.[8]

In 1896, she was assigned to the Northern Squadron, based in the English Channel. The unit was France's secondary battle fleet, and at that time, it also included the ironclad Hoche and four coastal defense ships, the armored cruiser Dupuy de Lôme, and the protected cruisers Friant and Coëtlogon.[9] She took part in the maneuvers that year, which were conducted from 6 to 26 July in conjunction with the local defense forces of Brest, Rochefort, Cherbourg, and Lorient. The squadron was divided into three divisions for the maneuvers, and Chasseloup-Laubat was assigned to the 2nd Division along with the coastal defense ships Valmy and Jemmapes and the aviso Salve, which represented part of the defending French squadron.[10]

Chasseloup-Laubat and both of her sister ships had been deployed to East Asia by January 1901 as part of the response to the Boxer Uprising in Qing China; at that time, six other cruisers were assigned to the station in addition to the three Friant-class ships.[11] She remained in East Asian waters in 1902.[12] She had returned to France at some point before 1907, when she embarked on a visit to the United States in company with the armored cruisers Victor Hugo and Kléber. The three ships departed Lorient on 8 May for Jamestown, Virginia, to participate in the Jamestown Exposition. By 20 May, they were visiting New York City; the ships returned to Jamestown on 31 May where they participated in the naval review presided over by President Theodore Roosevelt on 10 June. They returned to France later that month.[13][14]

In 1908, when she was assigned to 3rd Division of the Northern Squadron, along with the cruiser Descartes and the armored cruiser Kléber. By that time, the squadron included another seven armored cruisers and two other protected cruisers.[15][16] The ship was reduced to a hulk in 1911,[3] and was disarmed two years later. During World War I, she was used as a water distilling ship based in Mudros during the Gallipoli campaign and later with the main fleet at Corfu.[5][17][18] She was then transferred to Port Etienne to supply the French colony with water in 1920. For budgetary reasons, the Ministry of the Navy decommissioned the cruiser and sold it to French fishery "Société Industrielle de la Grande Pêche" in 1921.[19][20] She was used as a floating warehouse and as a cistern for drinking water brought once a month from the Canary Islands.[21] She was ultimately sunk in 1926 and became the first ship to be abandoned in the bay of Nouadhibou, Mauritania.[22][23][24][25]

Notes

- Ropp, pp. 195–197.

- Gardiner, pp. 310–311.

- Gardiner, p. 311.

- Garbett 1904, p. 563.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 193.

- Brassey 1895, p. 27.

- Weyl, p. 28.

- Barry, pp. 186–190.

- Brassey 1896, p. 62.

- Thursfield, p. 167.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 218.

- Brassey 1902, p. 51.

- Jordan & Caresse, p. 160.

- Sieche, pp. 150, 155, 157.

- Garbett 1908, p. 100.

- Brassey 1908, p. 49.

- Saint-Ramond 2019, p. 60.

- Les armées françaises dans la Grande guerre. Tome VIII (in French). ANNEXE 1. Ministère de la guerre, état-major de l'armée, service historique. 1924. p. 493.

- Pavé 1997, p. 17.

- Ruedel, Marcel, ed. (1922-12-19). "Mauritanie - l'industrie de la pêche". Les Annales coloniales (in French). Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Ruedel, Marcel, ed. (1923-01-12). "Mauritanie - la vie économique". Les Annales coloniales (in French). Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Pavé 1997, p. 18.

- "Largest Ship Graveyard in the World: Nouadhibou, Mauritania". Sometimes Interesting. 2013-07-25. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- United States Hydrographic Office (1952). Sailing Directions for the West Coasts of Spain, Portugal, and Northwest Africa and Off-lying Islands: Includes Azores, Madeira, Canary and Cape Verde Islands, and Africa Southward to Cape Palmas. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 241.

A stranded wreck (Chasseloup Laubat) lies 2 miles southeastward of the light at Port Etienne. A light buoy is moored close southeastward of the wreck.

- Sebe 2007, p. 82.

References

- Barry, E. B. (July 1896). "Naval Manoeuvres of 1895". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, D.C.: United States Office of Naval Intelligence. XV: 163–214. OCLC 727366607.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895). "Ships Building In France". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 19–28. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1896). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–71. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1902). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 47–55. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1908). "Chapter III: Comparative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 48–57. OCLC 496786828.

- Garbett, H., ed. (May 1904). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVIII (315): 560–566. OCLC 1077860366.

- Garbett, H., ed. (January 1908). "Naval Notes: France". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. LLI (359): 100–103. OCLC 1077860366.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-639-1.

- Pavé, Marc (1997). Documents figurant dans les archives de l'Afrique Occidentale française (série Affaires agricoles, sous-série Pêche).: Tableaux thematiques des dossiers 1 à 16 (PDF). série Affaires agricoles, sous-série Pêche (in French). Centre de recherches océanographiques de Dakar-Thiaroye.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- Saint-Ramond, Francine (2019). Les Désorientés: Expériences des soldats français aux Dardanelles et en Macédoine, 1915-1918 (in French). Presses de l’Inalco. p. 60. ISBN 978-2-85831-299-3.

- Sebe, Berny (2007). "Nouadhibou's rusty legacy" (PDF). Ship Management International. 7: 82–84.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sieche, Erwin F. (1990). "Austria-Hungary's Last Visit to the USA". Warship International. XXVII (2): 142–164. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1897). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Naval Manoeuvres in 1896". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 140–188. OCLC 496786828.

- Weyl, E. (1898). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Chapter II: The Progress of Foreign Navies". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 19–55. OCLC 496786828.