Fred Rose (politician)

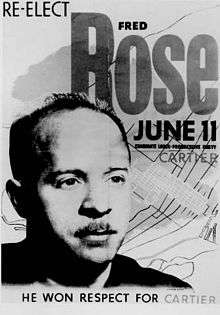

Fred Rose (born Fishel Rosenberg;[1] December 7, 1907 – March 16, 1983) was a Polish-Canadian politician and trade union organizer. A member of the Communist Party of Canada and Labor-Progressive Party, he is best known as the only member of the Canadian Parliament ever convicted of a charge related to spying for a foreign country.

Fred Rose | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Canadian Parliament for Cartier | |

| In office August 9, 1943 – January 30, 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Peter Bercovitch |

| Succeeded by | Maurice Hartt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Fishel Rosenberg December 7, 1907 Lublin, Russian Empire |

| Died | March 16, 1983 (aged 75) Warsaw, Poland |

| Political party | Labor-Progressive |

| Residence | Montreal, Quebec |

| Occupation | Electrician |

Early life

Rose was born to a Polish Jewish family in Lublin, which was then part of the Russian Empire and now is in Poland.[2] One of the six children in the family, he attended the "Gymnaste Humaniste de Lublin," a Jewish high school in which he learned to speak French. He emigrated to Canada as a child in 1920, where he attended Baron Byng High School.[3]

Communism

In 1925, he became involved with the Young Communist League of Canada[2] and then joined the Communist Party of Canada while he was working in a canning factory. By 1928, he became a person of interest for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.[2] In April 1931, he published the pamphlet "Smash the Embargo" in which he made his political goals clear. In his view, the Communist Party of Canada was to "lead the Canadian workers to establish a system similar to that of the Soviet Union."[4]

Rose was jailed during the 1930s for sedition, and won the hatred of Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis for writing about the close connections between the Duplessis government and the fascist governments of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. He was a close associate of Norman Bethune, a doctor who had aided antifascist and communist fighters first in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and later in China.

Electoral career

He was a candidate for the Communist Party of Canada in the working-class riding of Cartier, in the Montreal area in the 1935 federal election, coming in second with 16.28% of the votes. He ran in the 1936 Quebec general election in the riding of Montréal–Saint-Louis for the Communist Party of Quebec and came in third, at 16.8%.

In the early stages of World War II, the Communist Party of Canada was formally banned, and many of its leaders interned by the Padlock Law.[5] After a major public campaign, the party was legally reorganized as the Labor-Progressive Party. Rose won election to the House of Commons as an Labor-Progressive candidate from Cartier in a 1943 by-election.[2] He won with 30% of the vote in a tight four-way race, beating among others, David Lewis of the social democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). Rose was re-elected in the 1945 election with 40% of the vote. Most of the riding's immigrant Jewish population voted for Rose, who benefitted from the perception that the Soviet Union was the main hope for saving Europe's Jews from Hitler. Rose's main rival, Paul Massé, of the antiwar Bloc Populaire, who came second, was supported by most French-Canadians.

As a Member of Parliament, Rose proposed the first medicare legislation[1] and the first anti-hate legislation.[6]

Gouzenko affair

Rose was caught up in the world political sea change following World War II, when the Soviet Union, a major wartime ally, was now perceived as an enemy in the new reality of the Cold War. Igor Gouzenko, a young cipher clerk in the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, was recalled to his homeland in July 1945. Rather than return home, Gouzenko defected with documents in September 1945 and claimed to have evidence of a massive Soviet spy ring operating in Canada and the United States.[2]

Few took Gouzenko's accusations and evidence seriously at first. A royal commission of inquiry, the Kellock–Taschereau Commission, was ultimately established by the government of William Lyon Mackenzie King in February 1946 to investigate Gouzenko's evidence. Headed by two Supreme Court justices, Roy Kellock and Robert Taschereau, the commission arrested and sequestered Canadians named in Gouzenko's documents without legal counsel and barred them from all contact with the outside world until they were summoned before the commission.

Rose was alleged to lead the ring of up to 20 Soviet spies, which were targeting primarily atomic weapon research from the Manhattan Project. Raymond Boyer, an alleged co-conspirator, testified that Rose was involved in the operation. Rose refused to testify before the commission,[7] which he said was designed to "smear honest and patriotic Canadians." Rose was ultimately found guilty of conspiring to turn over information about the explosive RDX to the Soviets,[8] and was sentenced to prison for a term just one day longer than was required to deprive him of his elected seat in the House of Commons.

Rose wrote to Speaker Gaspard Fauteux from St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary on January 24, 1947:

Mr. Speaker: If the will of the people is to prevail, if justice is to be done, there can be no question of my expulsion from the house. To the contrary, I should be in my seat in the House of Commons and not in the penitentiary. Parliament is the highest of Courts. Through its actions in my case it will decide whether hysteria is to continue or whether reason and justice are to prevail. Respectfully, Fred Rose, M.P.

His letter was returned to him unread, and on January 30, 1947, he was formally expelled from the House of Commons.[4]

Later life

Rose was released from prison in 1951 after four-and-a-half years, with his health broken. Attempting to find work in Montreal, he was tailed from jobsite to jobsite by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which pointed out to employers and workmates that he was a convicted spy.

In 1953 he went to Poland to attempt to set up an import-export business and to obtain health treatment that he could not afford in Canada. He worked for many years as English-language editor of Poland, a magazine of Polish culture and civilization designed for sale in the West. While he lived in Poland, his Canadian citizenship was revoked in 1957, and he was unable to return to Canada to lead the fight to clear his name.[1]

His appeal against revoking his citizenship was denied, although Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Ellen Fairclough introduced the so-called "Fred Rose amendment" in 1958 to the Citizenship Act so that such a removal of Canadian citizenship could never happen again.[9] Years later, former federal cabinet minister Allan MacEachen acknowledged that the pages of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King's diary dealing with Rose had gone missing, as had most of the other records dealing with his case.

Rose died on March 16, 1983 in Warsaw, having never returned to Canada.[10]

Electoral record

Federal

| 1935 Canadian federal election: Cartier | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |||||

| Liberal | Samuel William Jacobs | 13,574 | 65.27 | |||||

| Communist | Fred Rosenberg (Rose) | 3,385 | 16.28 | |||||

| Independent Liberal | Paul-Emile Goyette | 1,531 | 7.36 | |||||

| Reconstruction | Salluste Lavery | 1,362 | 6.55 | |||||

| Conservative | Herman Julien | 945 | 4.54 | |||||

| Canadian federal by-election, August 9, 1943: Cartier Death of Peter Bercovitch | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | ||||

| Labor–Progressive | Fred Rose | 5,789 | 30.42 | |||||

| Bloc populaire | Paul Masse | 5,639 | 29.63 | |||||

| Liberal | Lazarus Phillips | 4,180 | 21.97 | –66.57 | ||||

| Co-operative Commonwealth | David Lewis | 3,313 | 17.41 | |||||

| Independent | Moses Miller | 109 | 0.57 | |||||

| Total valid votes | 19,030 | 100.00 | ||||||

| Labor–Progressive gain from Liberal | Swing | +0.40 | ||||||

| 1945 Canadian federal election: Cartier | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |||||

| Labor–Progressive | Fred Rose | 10,413 | 40.84 | |||||

| Liberal | Samuel Edgar Schwisberg | 8,935 | 35.04 | |||||

| Bloc populaire | Paul Masse | 6,148 | 24.11 | |||||

Provincial

| 1936 Quebec general election: Montréal–Saint-Louis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |||||

| Liberal | Peter Bercovitch | 2,024 | 58.83 | |||||

| Union Nationale | Louis-Gédéon Gravel | 773 | 22.47 | |||||

| Communist | Fred Rosenberg (Rose) | 578 | 16.80 | |||||

| Independent Union Nationale | Éphrem-J. Cuerrier | 65 | 1.88 | |||||

References

- Green, David B. (December 7, 2016). "This Day in Jewish History 1907: A Canadian MP and Russian Spy Is Born". Haaretz. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "Soviet Espionage in Canada, the Fred Rose Affair | David Levy". www.themontrealreview.com. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- Schnurmacher, Thomas (16 May 1986). "Class of 1960: Baron Byng Alumni Holding Anniversary Bash". The Montreal Gazette. Montreal. p. C1. ProQuest 431346565.

- Levy, David (2011-12-13). Stalin's Man in Canada: Fred Rose and Soviet Espionage. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 9781936274284.

- "Padlock Law", Wikipedia, 2018-10-14, retrieved 2019-02-20

- Reiter, Ester (2016-10-03). A Future Without Hate or Need: The Promise of the Jewish Left in Canada. Between the Lines. ISBN 9781771130172.

- "Fred Rose ~ Canada's Human Rights History". historyofrights.ca. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- "Soviet Spy Scandal". www.cbc.ca. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- "Evidence - February 15, 2017". Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Senate of Canada. February 15, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

I am sure my colleague from CIJA is aware that the last case of citizenship revocation on grounds of treason was to a Jewish Canadian citizen named Fred Rose, who at that time was seen as breaching what is called the fundamental betrayal of core values of Canada. He was a Communist and was convicted of conspiracy to disclose secrets to the Soviets. He didn't actually do it; he was convicted of conspiracy to do it. He had his citizenship revoked. It was the Conservative government of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker that introduced what was known as the 'Fred Rose amendment,' in 1958 so that it would never happen again.

- "Obituary of Fred Rose, Soviet spy - CBC Archives". Retrieved 2018-11-05.

Further reading

- Levy, David (2011). Stalin's Man in Canada: Fred Rose and Soviet Espionage. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1936274277.

- Sunstrum, Jim (reporter); Weisbord, Merrily (guest) (March 19, 1983). Obituary of Fred Rose, Soviet spy. Saturday Report (Television production). CBC Television. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Watson, Patrick (2003). "Fred Rose, the Member for Treason". The Canadians: Biographies of a Nation (Omnibus ed.). Toronto: McArthur & Company. pp. 544–559. ISBN 9781552783900.

- Weisbord, Merrily (1994). "The Fred Rose Case". The Strangest Dream: Canadian Communists, the Spy Trials, and the Cold War (2nd ed.). Montreal: Véhicule Press. ISBN 9781550650532.