Fitzrovia Chapel

The Fitzrovia Chapel is situated in Pearson Square, in the centre of the Fitzroy Place development, bordered by Mortimer Street, Cleveland Street, Nassau Street and Riding House Street in Fitzrovia, London. The chapel was designed by John Loughborough Pearson, and was built 1891-92, and though already in use, the interiors weren’t completed until 1929, overseen by his son Frank Loughborough Pearson.[1]

| Fitzrovia Chapel | |

|---|---|

Interior of the restored chapel in September 2017 | |

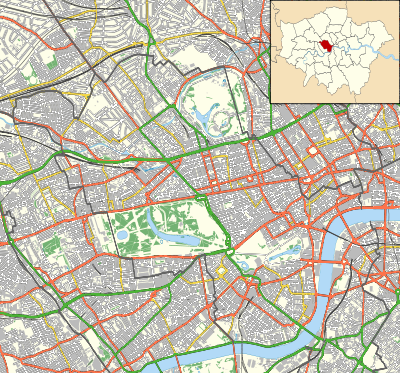

Fitzrovia Chapel Location in Central London | |

| 51.5190°N 0.1383°W | |

| Location | Fitzrovia, London |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Previous denomination | Church of England |

| Website | fitzroviachapel |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | Middlesex Hospital Chapel |

| Status | Hospital chapel |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Deconsecrated |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Architect(s) | John Loughborough Pearson, |

| Style | Victorian Gothic |

| Years built | 1891-92 |

| Closed | 2008 |

The chapel was built in the central courtyard of the former Middlesex Hospital, which was rebuilt in 1929-35 and subsequently demolished in 2008-15. The chapel was retained and it now stands in the Pearson Square development.

The chapel is a Grade II* listed building, noted for its opulent Gothic Revival style and opulent mosaic interior.[2]

History

.jpg)

The Fitzrovia Chapel was built in 1891-92 within the central courtyard of the Middlesex Hospital. Between 1929 and 1935, the decaying 18th-century hospital building was gradually demolished and rebuilt around the chapel.[3][4]

After a merger with University College Hospital, the Middlesex Hospital was completely demolished 2008-15 and replaced with a new residential development. The Grade II* chapel was retained throughout the demolition.[5][4] Today the chapel stands within Pearson Square, a privately owned public space of Jones Lang LaSalle, which was named after the chapel's architect.[6]

Architecture

The chapel is noted as a fine example of Gothic Revival architecture, designed by John Loughborough Pearson in an Italian Gothic style. The interior of the chapel features a rib vaulted ceiling decorated richly with much use of polychrome marble and mosaics. The mosaics were completed by Maurice Richard Josey in the 1930s, assisted by his son John L. Josey.[2]

The ceiling mosaic work consists of blue stars against a gold background representing the firmament. The wall mosaics are lined with green onyx and a zigzag pattern. In the arched chancel area there is a Cosmatesque pillar piscina. Set into an ogee arch is an aumbry adorned with an image of the Pelican in her Piety carved in white marble which was installed in memory of Prince Francis of Teck, the brother of Queen Mary, who died in 1910. Set into roundels beneath the arches are sculpted busts of the Twelve Apostles and the Old Testament prophets. At the west end, the organ gallery is surmounted by an arch decorated by a mosaic inscription of words from the Gloria in excelsis Deo.[2]

GLORIA IN EXCELSIS DEO ET IN TERRA PAX HOMINIBUS BONAE VOLUNTATIS

Glory be to God in the highest, and on earth peace and goodwill to all men.

The baptismal font is carved from a solid block of green marble and is adorned with the symbols presenting the Four Evangelists. The inscription, "Nipson anomemata me monan opsin", is a palindrome in Ancient Greek that was inscribed on a holy water font outside the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople in medieval times:[2]

Νίψον ἀνομήματα, μὴ μόναν ὄψιν)

"Wash the sins, not only the face"

Unusually, the chapel is aligned approximately on a North-South axis instead of the more traditional aligmnent towards liturgical east.[2]

Interior features

The baptistery

The baptistery A detail from an arch

A detail from an arch The decorated ceiling

The decorated ceiling The ceiling

The ceiling The aumbry

The aumbry

The Fitzrovia Chapel Foundation

The Fitzrovia Chapel is managed by a charity, the Fitzrovia Chapel Foundation. It is a secular chapel and is a venue for non-religious ceremonies such as weddings, civil partnerships, baby namings and memorials. The foundation has a licence from Westminster Council to conduct civil marriages and to supply alcohol.

Exhibitions and events

The chapel is also used by artists, galleries and art organisations for exhibitions. In May 2017, the Horiuchi Foundation presented a series of photographs at the chapel by Tomohiro Muda. The exhibition was called Icons of Time: Memories of the Tsunami that Struck Japan. Richard Ingleby Gallery hosted an exhibition during Frieze London in October 2017. Artists David Batchelor, Jonathan Owen, Kevin Harman and Peter Liversdge were included in it. In July 2017, Erskine, Hall & Coe presented Claudi Casanovas’s Minvant at the chapel. In 2016, the TJ Boulting gallery hosted Stephanie Quayle's Jenga at the Fitzrovia Chapel and in December 2017, Siân Davey's Looking for Alice.

As part of Frieze London, the Stephen Friedman Gallery has showed works by Yinka Shonibare MBE and Jonathan Baldock at the chapel. In January 2019, photographer Richard Ansett presented his portrait of the artist Grayson Perry at the chapel. It was called Birth and depicted Perry's alter ego, Claire.

The Fitzrovia Chapel has been used by recording artists including Katie Melua, Allman Brown and the Vickers Bovey Guitar Duo.

Fashion brands have used the chapel as a backdrop to shows, shoots and presentations. These have included Phoebe English, Alistair James, Mother of Pearl, Alighieri and Sharon Wauchob.

The Ward

Leading up to World AIDS Day in 2017, the chapel presented its first exhibition. Called The Ward, it followed the lives of four young men on the Broderip and Charles Bell wards in London’s former Middlesex Hospital. The Broderip was the first AIDS ward in London and was opened by Diana, Princess of Wales in 1987, this year marking the thirtieth anniversary of its opening. The photographer was Gideon Mendel who chronicled the wards in 1993. The exhibition was featured in The British Journal of Photography, Wallpaper, The Guardian, AnOther Magazine and on BBC News.

Nina Hamnett - 'Everybody was Furious'

The chapel's exhibition in 2019 focused on the Welsh artist (and former resident of Fitzrovia) Nina Hamnett. The exhibition was called Nina Hamnett - 'Everybody was Furious'. It featured little known pieces from Tenby Museum & Art Gallery, the town where the artist was born.

Portraits of NHS Heroes

Artist Tom Croft created a virtual exhibition (installed and scanned observing Covid-19 government guidelines) at the Fitzrovia Chapel, showcasing portraits of NHS staff created during the coronavirus crisis. Portraits for NHS Heroes includes work by 15 artists, all members of the Contemporary British Portrait Painters. The tour is available online.

Opening times

Each Wednesday between 11:00 and 16:00, the chapel is open to the public for visiting, quiet contemplation and reflection. There is no charge and booking is not required. There are volunteers on hand to answer questions.

The chapel offers an audio presentation on selected Wednesdays called Wireless Contemplation. They are linked to culturally significant themes which are important to the heritage of Fitzrovia. These have included a celebration of Dylan and Caitlin Thomas, Virginia Woolf, Oscar Wilde and Paul Verlaine. It is a chance to sit and reflect out of the distraction of the everyday. Details of these events are on the chapel website.

References

- "Our history". The Fitzrovia Chapel. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- Historic England. "Middlesex Hospital Chapel (Grade II*) (1223496)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- Rivett, Geoffrey (1986). The Development of the London Hospital System, 1823-1982. King Edward's Hospital Fund for London. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-724633-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Richardson, Ruth (29 March 2014). "Preserving the name of Middlesex Hospital Chapel". The Lancet. 383 (9923): 1120–1121. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60554-7. ISSN 0140-6736. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Aminoff, Michael Jeffrey (2016). Sir Charles Bell: His Life, Art, Neurological Concepts, and Controversial Legacy. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-061496-6. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Exemplar pay tribute to chapel architect in proposal for street name at Fitzroy Place". Fitzrovia News. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

External links

- Chapel interior of Google Street View