Festival

A festival is an event ordinarily celebrated by a community and centering on some characteristic aspect of that community and its religion or cultures. It is often marked as a local or national holiday, mela, or eid. A festival constitutes typical cases of glocalization, as well as the high culture-low culture interrelationship.[1] Next to religion and folklore, a significant origin is agricultural. Food is such a vital resource that many festivals are associated with harvest time. Religious commemoration and thanksgiving for good harvests are blended in events that take place in autumn, such as Halloween in the northern hemisphere and Easter in the southern.

Festivals often serve to fulfill specific communal purposes, especially in regard to commemoration or thanking to the gods and goddesses. Celebrations offer a sense of belonging for religious, social, or geographical groups, contributing to group cohesiveness. They may also provide entertainment, which was particularly important to local communities before the advent of mass-produced entertainment. Festivals that focus on cultural or ethnic topics also seek to inform community members of their traditions; the involvement of elders sharing stories and experience provides a means for unity among families.

In Ancient Greece and Rome, festivals such as the Saturnalia were closely associated with social organisation and political processes as well as religion.[2][3][4] In modern times, festivals may be attended by strangers such as tourists, who are attracted to some of the more eccentric or historical ones. The Philippines is one example of a modern society with many festivals, as each day of the year has at least one specific celebration. There are more than 42,000 known major and minor festivals in the country, most of which are specific to the barangay (village) level.[5]

Etymology

The word "festival" was originally used as an adjective from the late fourteenth century, deriving from Latin via Old French.[6] In Middle English, a "festival dai" was a religious holiday.[7] Its first recorded used as a noun was in 1589 (as "Festifall").[6] Feast first came into usage as a noun circa 1200,[8] and its first recorded use as a verb was circa 1300.[9] The term "feast" is also used in common secular parlance as a synonym for any large or elaborate meal. When used as in the meaning of a festival, most often refers to a religious festival rather than a film or art festival. In the Philippines and many other former Spanish colonies, the Spanish word fiesta is used to denote a communal religious feast to honor a patron saint.

The word gala comes from Arabic word khil'a, meaning robe of honor.[10] The word gala was initially used to describe "festive dress", but came to be a synonym of festival starting in the 18th century.[11]

Traditions

Many festivals have religious origins and entwine cultural and religious significance in traditional activities. The most important religious festivals such as Christmas, Rosh Hashanah, Diwali, Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha serve to mark out the year. Others, such as harvest festivals, celebrate seasonal change. Events of historical significance, such as important military victories or other nation-building events also provide the impetus for a festival. An early example is the festival established by Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses III celebrating his victory over the Libyans.[12] In many countries, royal holidays commemorate dynastic events just as agricultural holidays are about harvests. Festivals are often commemorated annually.

There are numerous types of festivals in the world and most countries celebrate important events or traditions with traditional cultural events and activities. Most culminate in the consumption of specially prepared food (showing the connection to "feasting") and they bring people together. Festivals are also strongly associated with national holidays. Lists of national festivals are published to make participation easier.[13]

Types of festivals

Religious festivals

Among many religions, a feast is a set of celebrations in honour of Gods or God.[14] A feast and a festival are historically interchangeable. Most religions have festivals that recur annually and some, such as Passover, Easter and Eid al-Adha are moveable feasts – that is, those that are determined either by lunar or agricultural cycles or the calendar in use at the time. The Sed festival, for example, celebrated the thirtieth year of an Egyptian pharaoh's rule and then every three (or four in one case) years after that.[15] Among the Ashantis, most of their traditional festivals are linked to gazette sites which are believed to be sacred with several rich biological resources in their pristine forms. Thus, the annual commemoration of the festivals helps in maintaining the buoyancy of the conserved natural site, assisting in biodiversity conservation.[16]

In the Christian liturgical calendar, there are two principal feasts, properly known as the Feast of the Nativity of our Lord (Christmas) and the Feast of the Resurrection, (Easter). In the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican liturgical calendars there are a great number of lesser feasts throughout the year commemorating saints, sacred events or doctrines. In the Philippines, each day of the year has at least one specific religious festival, either from Catholic, Islamic, or indigenous origins.

Buddhist religious festivals, such as Esala Perahera are held in Sri Lanka and Thailand.[17] Hindu festivals, such as Holi are very ancient. The Sikh community celebrates the Vaisakhi festival marking the new year and birth of the Khalsa.[18]

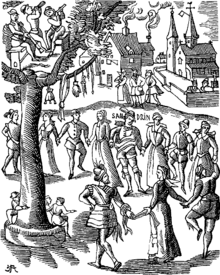

Cleaning in preparation for Passover (c.1320)

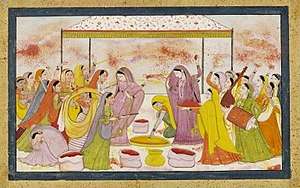

Cleaning in preparation for Passover (c.1320) Radha celebrating Holi, Kangra, India (c1788)

Radha celebrating Holi, Kangra, India (c1788)_-_A_Christmas_mass_at_the_church_of_the_holy_Sepulchre%2C_in_Bethlehem_(1).jpg)

- Moors and Christian festival in Villena, Spain

Decoration of god Krishna on Krishnashtami in India.

Decoration of god Krishna on Krishnashtami in India.

Arts festivals

Among the many offspring of general arts festivals are also more specific types of festivals, including ones that showcase intellectual or creative achievement such as science festivals, literary festivals and music festivals.[19] Sub-categories include comedy festivals, rock festivals, jazz festivals and buskers festivals; poetry festivals,[20] theatre festivals, and storytelling festivals; and re-enactment festivals such as Renaissance fairs. In the Philippines, aside from numerous art festivals scattered throughout the year, February is known as national arts month, the culmination of all art festivals in the entire archipelago.[21]

Film festivals involve the screenings of several different films, and are usually held annually. Some of the most significant film festivals include the Berlin International Film Festival, the Venice Film Festival and the Cannes Film Festival.

Pushkin Poetry Festival, Russia

Pushkin Poetry Festival, Russia Television studio at the Hôtel Martinez during the Cannes Film Festival, France (2006)

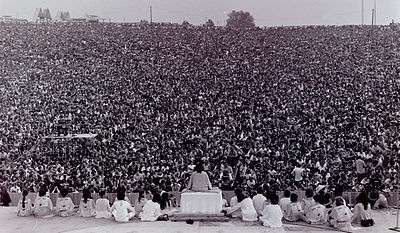

Television studio at the Hôtel Martinez during the Cannes Film Festival, France (2006) The opening ceremony at the Woodstock rock festival, United States (1969)

The opening ceremony at the Woodstock rock festival, United States (1969)

Food and drink festivals

A food festival is an event celebrating food or drink. These often highlight the output of producers from a certain region. Some food festivals are focused on a particular item of food, such as the National Peanut Festival in the United States, or the Galway International Oyster Festival in Ireland. There are also specific beverage festivals, such as the famous Oktoberfest in Germany for beer. Many countries hold festivals to celebrate wine. One example is the global celebration of the arrival of Beaujolais nouveau, which involves shipping the new wine around the world for its release date on the third Thursday of November each year.[22][23] Both Beaujolais nouveau and the Japanese rice wine sake are associated with harvest time. In the Philippines, there are at least two hundred festivals dedicated to food and drinks.

- Soweto Wine Festival, South Africa (2009)

Holi Nepal (2011)

Holi Nepal (2011)_-_Spain%2C_Bu%C3%B1ol_30.jpg) La Tomatina, Spain (2010)

La Tomatina, Spain (2010)- Beer horse cart from the Hofbräuhaus brewery at Oktoberfest Germany (2013)

Seasonal and harvest festivals

Seasonal festivals, such as Beltane, are determined by the solar and the lunar calendars and by the cycle of the seasons, especially because of its effect on food supply, as a result of which there is a wide range of ancient and modern harvest festivals. Ancient Egyptians relied upon the seasonal inundation caused by the Nile River, a form of irrigation, which provided fertile land for crops.[24] In the Alps, in autumn the return of the cattle from the mountain pastures to the stables in the valley is celebrated as Almabtrieb. A recognized winter festival, the Chinese New Year, is set by the lunar calendar, and celebrated from the day of the second new moon after the winter solstice. Dree Festival of the Apatanis living in Lower Subansiri District of Arunachal Pradesh is celebrated every year from July 4 to 7 by praying for a bumper crop harvest.[25]

Midsummer or St John's Day, is an example of a seasonal festival, related to the feast day of a Christian saint as well as a celebration of the time of the summer solstice in the northern hemisphere, where it is particularly important in Sweden. Winter carnivals also provide the opportunity to utilise to celebrate creative or sporting activities requiring snow and ice. In the Philippines, each day of the year has at least one festival dedicated to harvesting of crops, fishes, crustaceans, milk, and other local goods.

Temple Festival in India

Temple Festival in India

Midsummer dance by Anders Zorn, Sweden (1897)

Midsummer dance by Anders Zorn, Sweden (1897)

Grand Parade at the Sydney Royal Easter Show, Australia (2009)

Grand Parade at the Sydney Royal Easter Show, Australia (2009) Halloween pumpkins show the close relationship between a harvest and religious festivals

Halloween pumpkins show the close relationship between a harvest and religious festivals

Study of festivals

- Festive ecology – explores the relationships between the symbolism and the ecology of the plants, fungi and animals associated with cultural events such as festivals, processions and special occasions.

- Heortology – the study of religious festivals. It was originally only used in respect of Christian festivals,[26] but it now covers all religions, in particular those of Ancient Greece.[27] See list of foods with religious symbolism for some topical overlap.

See also

- All pages with titles containing Festival

- Philippine fiestas

- Convention

- Event planning

- Fair

- Festive ecology

- Holiday

- Lists of festivals

- Outline of festivals

- Procession

- Trade show

References

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 264.

- Robertson, Noel (1992). Festivals and legends: the formation of Greek cities in the light of public ritual (Repr. ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802059880.

- Brandt, edited by J. Rasmus; Iddeng, Jon W. (2012). Greek and Roman festivals : content, meaning, and practice (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-969609-3.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur (1953). The dramatic festivals of Athens (2nd ed.). Oxford: At the Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198142587.

- Picard, David; Robinson, Mike (2006). "Remaking Worlds: Festivals, Tourism and Change". In David Picard and Mike Robinson (ed.). Festivals, Tourism and Social Change. Channel View Publications. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-84541-267-8.

- "festival, adj. and n.". OED Online. March 2014. Oxford University Press. Accessed April 16, 2014.

- festival (adj.) at the Middle English Dictionary. Accessed April 16, 2014.

- "feast, n.". OED Online. March 2014. Oxford University Press. Accessed April 16, 2014.

- "feast, v.". OED Online. March 2014. Oxford University Press. Accessed April 16, 2014.

- James E Glevin. The Modern Middle East: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 21.

- "gala (n.)".

- Berrett, LaMar C.; Ogden D. Kelly (1996). Discovering the world of the Bible (3rd ed., rev. ed.). Provo, Utah: Grandin Book Co. p. 289. ISBN 0-910523-52-5.

- See for example: List of festivals in Australia; Bangladesh; Canada; China; Colombia; Costa Rica; Fiji; India; Indonesia; Iran; Japan; Laos; Morocco; Nepal; Pakistan; Philippines; Romania; Tunisia; Turkey; United Kingdom; United States; Vietnam.

- Ancient Egyptian festivals could be either religious or political.Bleeker, C. J. (1968) [1967]. Egyptian festivals. Enactments of religious renewal. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill.

- "Heb-Sed (Egyptian feast)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Robson, James P. (2007). "Local approaches to biodiversity conservation: lessons from Oaxaca, southern Mexico". International Journal of Sustainable Development. 10 (3): 267. doi:10.1504/ijsd.2007.017647. ISSN 0960-1406.

- Gerson, Ruth (1996). Traditional festivals in Thailand. Kuala Lumpur; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9676531111.

- Roy, Christian (2005). "Sikh Vaisakhi: Anniversary of the Pure". Traditional Festivals, Vol. 2 [M – Z]: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 480. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- See List of music festivals.

- Some such as such as Cúirt International Festival of Literature started as a poetry festival and then broadened in scope.

- Kasilag, Giselle P. (February 1999). "Performances, exhibits around the country mark National Arts Month". BusinessWorld (SanJuan, Philippines): 1. ISSN 0116-3930 – via Nexis Uni.

- Hyslop, Leah (November 21, 2013). "Beaujolais Nouveau day: 10 facts about the wine". The Telegraph.

- Haine, W. Scott (2006). Culture and Customs of France. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-313-32892-3.

- Bunson, Margaret (2009). "Nile festivals". Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Infobase Publishing. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-4381-0997-8.

- "Press release – Dree festival". Directorate of Information, Govt of Arunachal Pradesh. July 5, 2004. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Robert Parker: Athenian Religion

Further reading

- Ian Yeoman, ed. (2004). Festival and events management: an international arts and culture perspective (1st ed., repr. ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 9780750658720.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Festivals. |