Fanny Hill

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure—popularly known as Fanny Hill (possibly an anglicisation of the Latin mons veneris, mound of Venus)[1]—is an erotic novel by English novelist John Cleland first published in London in 1748. Written while the author was in debtors' prison in London,[2][3] it is considered "the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel".[4] It is one of the most prosecuted and banned books in history.[5]

One of earliest editions, 1749 (MDCCXLIX) | |

| Author | John Cleland |

|---|---|

| Original title | Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure |

| Country | Great Britain |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Erotic novel |

Publication date | 21 November 1748; February 1749 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| OCLC | 13050889 |

| 823/.6 19 | |

| LC Class | PR3348.C65 M45 |

.jpg)

The book exemplifies the use of euphemism. The text has no "dirty words" or explicit scientific terms for body parts, but uses many literary devices to describe genitalia. For example, the vagina is sometimes referred to as "the nethermouth", which is also an example of psychological displacement.

A critical edition by Peter Sabor includes a bibliography and explanatory notes.[6] The collection Launching "Fanny Hill" contains several essays on the historical, social and economic themes underlying the novel.[7]

Publishing history

The novel was published in two installments, on 21 November 1748 and in February 1749, by Fenton Griffiths and his brother Ralph under the name "G. Fenton".[8] There has been speculation that the novel was at least partly written by 1740, when Cleland was stationed in Bombay as a servant of the British East India Company.[9]

Initially, there was no governmental reaction to the novel. However, in November 1749, a year after the first instalment was published, Cleland and Ralph Griffiths were arrested and charged with "corrupting the King's subjects". In court, Cleland renounced the novel and it was officially withdrawn.

As the book became popular, pirate editions appeared. It was once believed that the scene near the end, in which Fanny reacts with disgust at the sight of two young men engaging in anal intercourse,[10] was an interpolation made for these pirated editions, but the scene is present in the first edition (p. xxiii). In the 19th century, copies of the book sold underground in the UK, the US and elsewhere.[11] In 1887, a French edition appeared with illustration by Édouard-Henri Avril.

The book eventually made its way to the United States. In 1821, a Massachusetts court outlawed Fanny Hill. The publisher, Peter Holmes, was convicted for printing a "lewd and obscene" novel. Holmes appealed to the Massachusetts Supreme Court. He claimed that the judge, relying only on the prosecution's description, had not even seen the book. The state Supreme Court wasn't swayed. The Chief Justice wrote that Holmes was "a scandalous and evil disposed person" who had contrived to "debauch and corrupt" the citizens of Massachusetts and "to raise and create in their minds inordinate and lustful desires".

Mayflower (UK) edition

In 1963, after the 1960 court decision in R v Penguin Books Ltd that allowed the continuing publication of Lady Chatterley's Lover, Gareth Powell's Mayflower Books published an uncensored paperback version of Fanny Hill. The police became aware of the 1963 edition a few days before publication, having spotted a sign in the window of the Magic Shop in Tottenham Court Road in London, run by Ralph Gold. An officer went to the shop, bought a copy, and delivered it to Bow Street magistrate Sir Robert Blundell, who issued a search warrant. At the same time, two officers from the vice squad visited Mayflower Books in Vauxhall Bridge Road to determine whether copies of the book were kept on the premises. They interviewed the Powell, the publisher, and took away the five copies there. The police returned to the Magic Shop and seized 171 copies of the book, and in December, Gold was summonsed under section 3 of the Obscene Publications Act 1959. By then, Mayflower had distributed 82,000 copies of the book, but it was Gold who was being tried, although Mayflower covered the legal costs. The trial took place in February 1964. The defence argued that Fanny Hill was a historical source book and that it was a joyful celebration of normal non-perverted sex—bawdy rather than pornographic. The prosecution countered by stressing one atypical scene involving flagellation, and won. Mayflower elected not to appeal.

Luxor Press published a 9/6 edition in January 1964, using text "exactly the same as that employed for the de-luxe edition" in 1963. The back cover features praise from The Daily Telegraph and from the author and critic Marghanita Laski. It went through many reprints in the first couple of years.

The Mayflower case highlighted the growing disconnect between the obscenity laws and the permissive society that was developing in late 1960s Britain, and was instrumental in shifting views to the point where in 1970 an uncensored version of Fanny Hill was again published in Britain.

1960s US edition: prosecutions and court rulings

In 1963, Putnam published the book in the United States under the title John Cleland's Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. This edition led to the arrest of New York City bookstore owner Irwin Weisfeld and clerk John Downs[12][13] as part of an anti-obscenity campaign orchestrated by several major political figures.[14][15] Weisfeld's conviction[16] was eventually overturned in state court and New York ban of Fanny Hill lifted.[17] The new edition was also banned for obscenity in Massachusetts, after a mother complained to the state's Obscene Literature Control Commission.[11] Massachusetts high court did rule Fanny Hill obscene[18] and the publisher's challenge to the ban now went up to the Supreme Court. In a landmark decision in 1966, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Memoirs v. Massachusetts that Fanny Hill did not meet the Roth standard for obscenity.[19]

Associate Justice William O. Douglas cited five primary defenses of the ruling:

- Since the First Amendment forbids censorship of expression of ideas not linked with illegal action, Fanny Hill cannot be proscribed. Pp. 383 U. S. 426; 383 U. S. 427–433

- Even under the prevailing view of the Roth test the book cannot be held to be obscene in view of substantial evidence showing that it has literary, historical, and social importance. P. 383 U. S. 426.

- Since there is no power under the First Amendment to control mere expression, the manner in which a book that concededly has social worth is advertised and sold is irrelevant. P. 383 U. S. 427.

- There is no basis in history for the view expressed in Roth that "obscene" speech is "outside" the protection of the First Amendment. Pp. 383 U. S. 428–431.

- No interest of society justifies overriding the guarantees of free speech and press and establishing a regime of censorship. Pp. 383 U. S. 431–433" (414).[19]

The art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann recommended the work in a letter for "its delicate sensitivities and noble ideas" expressed in "an elevated Pindaric style".[20]

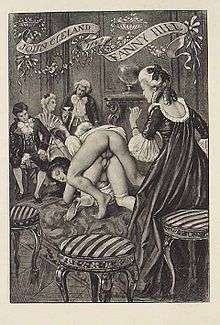

Illustrations

.jpg)

The original work was not illustrated, but many editions of this book have contained illustrations, often depicting the novel's sexual content. Distributors of the novel such as John Crosby were imprisoned for "exhibiting [not selling] to sundry persons a certain lewd and indecent book, containing very lewd and obscene pictures or engravings". Sellers of the novel such as Peter Holmes were imprisoned and charged that they "did utter, publish and deliver to one [name]; a certain lewd, wicked, scandalous, infamous and obscene print, on paper, was contained in a certain printed book then and there uttered, [2] published and delivered by him said Peter Holmes intitled "Memoirs of a Woman Of Pleasure" to manifest corruption and subversion of youth, and other good citizens ... "[21]

None of the story's scenes have been exempt from illustration. Illustrations of this novel vary from the first homosexual experience to the flagellation scene.

Although editions of the book have frequently featured illustrations, many have been of poor quality.[22] An exception to this is the set of mezzotints, probably designed by the artist George Morland and engraved by his friend John Raphael Smith that accompanied one edition.

Plot

The novel consists of two long letters (which appear as volumes I and II of the original edition) written by Frances 'Fanny' Hill, a rich Englishwoman in her middle age, who leads a life of contentment with her loving husband Charles and their children, to an unnamed acquaintance identified only as 'Madam.' Fanny has been prevailed upon by 'Madam' to recount the 'scandalous stages' of her earlier life, which she proceeds to do with 'stark naked truth' as her governing principle.

The first letter begins with a short account of Fanny's impoverished childhood in a Lancashire village. At age 14, she loses her parents to smallpox, arrives in London to look for domestic work, and gets lured into a brothel. She sees a sexual encounter between an ugly older couple and another between a young attractive couple, and participates in a lesbian encounter with Phoebe, a bisexual prostitute. A customer, Charles, induces Fanny to escape. She loses her virginity to Charles and becomes his lover. Charles is sent away by deception to the South Seas, and Fanny is driven by desperation and poverty to become the kept woman of a rich merchant named Mr H—. After enjoying a brief period of stability, she sees Mr H— have a sexual encounter with her own maid, and goes on to seduce Will (the young footman of Mr H—) as an act of revenge. She is discovered by Mr H— as she is having a sexual encounter with Will. After being abandoned by Mr H—, Fanny becomes a prostitute for wealthy clients in a pleasure-house run by Mrs Cole. This marks the end of the first letter.

The second letter begins with a rumination on the tedium of writing about sex and the difficulty of driving a middle course between vulgar language and "mincing metaphors and affected circumlocutions". Fanny then describes her adventures in the house of Mrs Cole, which include a public orgy, an elaborately orchestrated bogus sale of her "virginity" to a rich dupe called Mr Norbert, and a sado-masochistic session with a man involving mutual flagellation with birch-rods. These are interspersed with narratives which do not involve Fanny directly; for instance, three other girls in the house (Emily, Louisa and Harriett) describe their own losses of virginity, and the nyphomaniac Louisa seduces the immensely endowed but imbecilic "good-natured Dick". Fanny also describes anal intercourse between two older boys (removed from several later editions). Eventually Fanny retires from prostitution and becomes the lover of a rich and worldly-wise man of 60 (described by Fanny as a "rational pleasurist"). This phase of Fanny's life brings about her intellectual development, and leaves her wealthy when her lover dies of a sudden cold. Soon after, she has a chance encounter with Charles, who has returned as a poor man to England after being shipwrecked. Fanny offers her fortune to Charles unconditionally, but he insists on marrying her.

The novel's developed characters include Charles, Mrs Jones (Fanny's landlady), Mrs Cole, Will, Mr H— and Mr Norbert. The prose includes long sentences with many subordinate clauses. Its morality is conventional for the time, in that it denounces sodomy, frowns upon vice and approves of only heterosexual unions based upon mutual love.[23]

Analysis

The plot was described as 'operatic' by John Hollander, who said that "the book's language and its protagonist's character are its greatest virtues".[24]

Literary critic Felicity A. Nussbaum describes the girls in Mrs Cole's brothel as "'a little troop of love' who provide compliments, caresses, and congratulation to their fellow whores' erotic achievements".[25]

According to literary critic Thomas Holmes, Fanny and Mrs Cole see the homosexual act thusly: "the act subverts not only the hierarchy of the male over the female, but also what they consider nature's law regarding the role of intercourse and procreation".[26]

Themes and genre

Metonymy

There are numerous scholars who claim that Fanny's name refers to a woman's vagina. However, this interpretation lacks corroborating evidence: the term "fanny" is first known to have been used to mean female genitalia in the 1830s, and no 18th-century dictionary defines "fanny" in this way.[27]

Disability

Later in the text when Fanny is with Louisa, they come across a boy nicknamed "Good-natured Dick" who is described as having some mental disability/handicap. Louisa brings the boy in anyway, as Dick's functioning physical state supersedes his poor mental one. This scene also leads into an issue within the text of rape (for both Dick and Louisa) and how the possible label of rape is removed by resistance transitioning into pleasure.[28]

Bildungsroman

One scholar, David McCracken, writes about Fanny Hill as a bildungsroman. Her sexual development contains three life stages: innocence, experimentation, and experience.[29] McCracken specifically addresses how Fanny's word selections on describing the phallus change throughout the stages. Fanny sees the phallus as both an object of terror and of delight. McCracken relates her changing view of the phallus to Burke's theory of the sublime and beautiful.

Shame

Patricia Spacks discusses how Fanny has been previously deprived by her rural environment of what she can understand as real experience, and how she welcomes the whores' efforts to educate her.[30] Since Fanny is so quickly catapulted into her new life, she has had little time to reflect on the shame and regret that she feels for leading a life of adultery, and replaces this shame with the pleasure of sexual encounters with men and women. Even though these feelings may have been replaced or forgotten, she still reflects on her past: "...and since I was now bent over the bar, I thought by plunging over head and ears into the stream I was hurried away by, to drown all sense of shame or reflection".[31] Having little time to think about how she feels about her transition, she masks her thoughts with sexual pleasure, yet this is not a total fix to forget her emotions.

Narrative voice

Andrea Haslanger argues in her dissertation how the use of first-person narrative in the 18th-century "undermines, rather than secures, the individual" in classic epistolary novels like Roxanna, Evelina, Frankenstein, and specifically Fanny Hill. Haslanger claims that "the paradox of pornographic narration is that it mobilizes certain aspects of the first person (the description of intimate details) while eradicating others (the expression of disagreement or resistance)" (19).[32] With this in mind, she raises the question of "whether 'I' denotes consciousness or body or both" (34).

Fanny Hill versus the traditional conduct novel

With sexual acts being viewed heavily as taboo within 18th-century England, Fanny Hill strayed far away from the norm in comparison to other works of its time. A large portion of books that focused on the idea of sex were written in the form of conduct novels: books that would focus on teaching women the proper ways to behave and live their lives in as virtuous of a manner as possible.[33] These novels encouraged women to stay away from sexual deviance, for if they were to remain virtuous then they would ultimately be rewarded. One example of this is Samuel Richardson's conduct novel Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded, in which the character of Pamela is able to resist sexual temptation, thus maintaining her virtue and being rewarded in the end with a prosperous life.

However, Fanny Hill was widely considered to be the first work of its time to focus on the idea of sexual deviance being an act of pleasure, rather than something that was simply shameful. This can be seen through Fanny's character partaking in acts that would normally be viewed as deplorable by society's standards, but then is never punished for them. In fact, Fanny is ultimately able to achieve her own happy ending when she is able to find Charles again, marrying him and living in a life of wealth. This can be viewed in sharp contrast to a work like Pamela, where sexual acts are heavily avoided for the sake of maintaining virtue. Meanwhile, within Fanny Hill, normally deplorable acts can be conducted with little to no consequence.

Literary and film adaptations

Because of the book's notoriety (and public domain status), numerous adaptations have been produced. Some of them are:

- Fanny, Being the True History of the Adventures of Fanny Hackabout-Jones (1980) (a retelling of 'Fanny Hill' by Erica Jong purports to tell the story from Fanny's point of view, with Cleland as a character she complains fictionalised her life).

- Fanny Hill (US/West Germany, 1964), starring Letícia Román, Miriam Hopkins, Ulli Lommel, Chris Howland; directed by Russ Meyer, Albert Zugsmith (uncredited)[34]

- The Notorious Daughter of Fanny Hill (US, 1966), starring Stacy Walker, Ginger Hale; directed by Peter Perry (Arthur Stootsbury).

- Fanny Hill (Sweden, 1968), starring Diana Kjær, Hans Ernback, Keve Hjelm, Oscar Ljung; directed by Mac Ahlberg[35]

- Fanny Hill (West Germany/UK, 1983), starring Lisa Foster, Oliver Reed, Wilfrid Hyde-White, Shelley Winters; directed by Gerry O'Hara[36]

- Paprika (Italy, 1991), starring Debora Caprioglio, Stéphane Bonnet, Stéphane Ferrara, Luigi Laezza, Rossana Gavinel, Martine Brochard and John Steiner; directed by Tinto Brass.[37]

- Fanny Hill (US, 1995), directed by Valentine Palmer.[38]

- Fanny Hill (Off-Broadway Musical, 2006), libretto and score by Ed Dixon, starring Nancy Anderson as Fanny.

- Fanny Hill (UK, 2007), written by Andrew Davies for the BBC and starring Samantha Bond and Rebecca Night.[39]

Comic strip adaptations

Erich von Götha de la Rosière adapted the novel into a comic book version.

References in popular culture

References in literary works

- 1952: In the preface to Henry Miller’s book The Books in my Life, he asks: "Why, if it is so 'dull', has it not become a 'classic' by now, free to circulate in drug stores, railway stations and other innocent places? It is just two hundred years since it first appeared, and it has never gone out of print, as every American tourist in Paris well knows."[40]

- 1965: In Harry Harrison's novel Bill, the Galactic Hero, the titular character is stationed on a starship named Fanny Hill.

- 1966: In Lita Grey's book, My Life With Chaplin, she claims that Charlie Chaplin "whispered references to some of Fanny Hill's episodes" to arouse her before making love.

- 1984: In the book Frost at Christmas by R. D. Wingfield, the vicar has a copy of Fanny Hill hidden in his trunk amongst other dirty books.

- 1993: In Diana Gabaldon's novel Voyager, in a scene set in 1758, the male protagonist Jamie Fraser reads a borrowed copy of Fanny Hill.

- 1999: In the first volume of Alan Moore's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Fanny Hill is depicted as a member of the 18th century version of the League. She also appears in "The Black Dossier" as a member of Gulliver's League, as well as a "sequel" to the original Hill novel, with illustrations by Kevin O'Neill.

- 2016: In the book The Butcher's Hook by Janet Ellis, set in 1763, the father of beautiful Anne Jaccob is found by his daughter sneaking a read of Fanny Hill in his study. He hides the book immediately and says "Dull, very dull".

References in film, television, musical theatre and song

- 1965: The novel is mentioned in Tom Lehrer's song "Smut" in the album That Was the Year That Was:

I thrill

To any book like Fanny Hill,

And I suppose I always will,

If it is swill

And really fil-

thy. - 6 December 1965: In series 4, episode 3 of BBC sitcom Meet the Wife, entitled "Brother Tom", Fred reacts to Thora's suspicions of a young woman staying at their house by saying, "You've never been the same since you read Fanny Hill!"

- The 1968 version of Yours, Mine, and Ours, Henry Fonda's character, Frank Beardsley, gives some fatherly advice to his stepdaughter. Her boyfriend is pressuring her for sex and Frank says boys tried the same thing when he was her age. When she tries to tell him that things are different now he observes, "I don't know, they wrote Fanny Hill in 1742 [sic] and they haven't found anything new since."

- In the 1968 David Niven, Lola Albright film The Impossible Years, the younger daughter of Niven's character is seen reading Fanny Hill, whereas his older daughter, Linda, is seen reading Sartre.

- 23 November 1972: An episode of Monty Python's Flying Circus titled "The War Against Pornography" featured a sketch that parodied the exploitation of sex on television for ratings, in which John Cleese played the narrator of a documentary on molluscs who adds sexualised imagery to maintain his audience's interest; when discussing the clam, he describes it as "a cynical, bed-hopping, firm-breasted, Rabelaisian bit of seafood that makes Fanny Hill look like a dead Pope."

- 1974: In the film The Groove Tube, children's TV show host Koko the Clown (Ken Shapiro) asks the children in his audience to send their parents out of the room during "make believe time". He then reads an excerpt from page 47 of Fanny Hill in response to a viewer's request.[41]

- The TV Series M*A*S*H referenced the book three times in the second half of the 1970s: in the season 4 episode "The Price of Tomato Juice",[42] Radar thanks Sparky for sending the book Fanny Hill but says the last chapter was missing and asks "Who did it?" He repeats back Sparky's answer: "Everybody"; in another season 4 episode "Some 38th Parallels", Hawkeye tells Colonel Potter that he was reading Fanny Hill in the back of a truck on top of a pile of rotting peaches, saying that when the truck hit a bump he was "in heaven"; in the season 6 episode "Major Topper", Hawkeye tells a person knocking on the door to "go read Fanny Hill". The person at the door is Father Mulcahy, and B.J. Hunnicutt pretends that Fanny Hill was a famous nurse. Hawkeye comments, "Yeah, she made a lot of soldiers very happy in World War I."

- In the 2006–07 Broadway musical Grey Gardens, young Edith Bouvier Beale (aka "little Edie") sings "Girls who smoke and read Fanny Hill / Well I was reading De – Toc – que – ville".

See also

References

- Sutherland, John (14 August 2017). "Fanny Hill: why would anyone ban the racy novel about 'a woman of pleasure'?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Wagner, "Introduction", in Cleland, Fanny Hill, 1985, p. 7.

- Lane, Obscene Profits: The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age, 2000, p. 11.

- Foxon, Libertine Literature in England, 1660–1745, 1965, p. 45.

- Browne, Ray Broadus; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- Oxford World's Classics, 1985.

- Patsy S. Fowler and Alan Jackson, eds. Launching "Fanny Hill": Essays on the Novel and Its Influences. New York: AMS Press, 2003.

- Roger Lonsdale, "New attributions to John Cleland", The Review of English Studies 1979 XXX(119):268–290 doi:10.1093/res/XXX.119.268

- Gladfelder, Hall, Fanny Hill in Bombay, The Making and Unmaking of John Cleland, Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2012.

- Kopelson, K. (1992). "Seeing sodomy: Fanny Hill's blinding vision". Journal of Homosexuality. 23 (1–2): 173–183. doi:10.1300/J082v23n01_09. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 1431071.

- Graham, Ruth. "How 'Fanny Hill' stopped the literary censors". Boston Globe. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- "Judges Convict Two for 'Fanny Hill' Sale". New York Daily News. 15 November 1963.

- Bates, Stephen (3-1-2010). "Father Hill and Fanny Hill: an Activist Group's Crusade to Remake Obscenity Law". UNC / First Amendment Law Review. 8 (2): 49. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Bates, Stephen. "Father Hill and Fanny Hill: an Activist Group's Crusade to Remake Obscenity Law". UNC / First Amendment Law Journal. 8 (2): 2.

- Collins, Ronald K. L.; Skover, David M. (2002). The Trials of Lenny Bruce. Sourcebooks MediaFusion. ISBN 1570719861.

- Bookcase, inc, defendant-appellant. "The people of the State of New York, respondent, against The Bookcase, inc., Irwin Weisfeld, and John Downs, defendants-appellants". nypl.org. New York Public Library.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "State Court Lifts 'Fanny Hill' Ban". New York Times. 11 July 1964.

- Bates, Stephen (3-1-2010). "Father Hill and Fanny Hill: An Activist Group' s Crusade to Remake Obscenity Law". UNC / First Amendment Law Review. 8 (2): 59 (of .pdf) or 274 of doc. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "A Book Named "John Cleland's Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure" et al. v. Attorney General of Massachusetts" (PDF). Princeton University. October 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2018 – via HeinOnline.

- Winckelmann, Briefe, H. Diepolder and W. Rehm, eds., (1952–1957) vol. II:111 (no. 380) noted in Thomas Pelzel, "Winckelmann, Mengs and Casanova: A Reappraisal of a Famous Eighteenth-Century Forger", The Art Bulletin, 54.3 (September 1972:300–315) p. 306 and note.

- McCorison, Marcus A. (1 June 2010). "Printers and the Law: The Trials of Publishing Obscene Libel in Early America". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. 104 (2): 181–217. doi:10.1086/680925. ISSN 0006-128X.

- Hurwood, p. 179

- Cleland John, Memoirs of a woman of pleasure, ed. Peter Sabor, Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Hollander, John: "The old last act: some observations on Fanny Hill", Encounter, October 1963.

- Nussbaum, Felicity (1995). "One part of womankind: prostitution and sexual geography in 'Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure'". Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 7 (2): 16–41 – via Academic OneFile.

- Holmes, Thomas Alan (2009). "Sexual Positions and Sexual Politics: John Cleland's Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure". South Atlantic Review. 74 (1): 124–139. eISSN 2325-7970. ISSN 0277-335X. JSTOR 27784834.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spedding, Patrick; Lambert, James (2011). "Fanny Hill, Lord Fanny, and the Myth of Metonymy". Studies in Philology. 108 (1): 108–132. doi:10.1353/sip.2011.0001. ISSN 1543-0383. S2CID 161549305.

- Haslanger, Andrea (2011). "What Happens When Pornography Ends in Marriage: The Uniformity of Pleasure in "Fanny Hill"". ELH. 78 (1): 163–188. doi:10.1353/elh.2011.0002. eISSN 1080-6547. ISSN 0013-8304. JSTOR 41236538. PMID 21688452. S2CID 32906838.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCracken, David (October 2016). "A Burkean Analysis of the Sublimity and the Beauty of the Phallus in John Cleland's Fanny Hill". ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews. 29 (3): 138–141. doi:10.1080/0895769X.2016.1216388 – via MLA Bibliography.

- Spacks, Patricia Meyer (1987). "Female Changelessness; Or, What Do Women Want?". Studies in the Novel. 19 (3, Women and Early Fiction): 273–283. ISSN 0039-3827. JSTOR 29532507.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cleland, John (2008). Memoirs of a woman of pleasure. Oxford Univ. Press. p. 78.

- Haslanger, Andrea (2011). The Story of I: First Persons and Others In Eighteenth-Century Narrative. UMI.

- Sachidananda, Mohanty (2004). "Female Identity and Conduct Book Tradition in Orissa: The Virtuous Woman in the Ideal Home". Economic and Political Weekly. 39: 333–336.

- Fanny Hill (1964) on IMDb

- Fanny Hill (1968) on IMDb

- Fanny Hill (1983) on IMDb

- Paprika on IMDb

- Fanny Hill (1995) on IMDb

- Article from The Guardian

- Miller, Henry (1952). The Books in my Life. New York: New Directions. p. 17.

- Fédération française des ciné-clubs (1975). Cinéma. 200–202. Fédération française des ciné-clubs. p. 300.

- MashEpisodeGuide

Bibliography

- Browne, Ray Broadus; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- Cleland, John (1985). Fanny Hill Or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-043249-7.

- Foxon, David. Libertine Literature in England, 1660–1745. New Hyde Park: University Books, 1965.

- Gladfelder, Hal Fanny Hill in Bombay: The Making and Unmaking of John Cleland, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012

- Hurwood, Bernhardt J. The Golden age of erotica, Tandem, ISBN 0-426-02030-8, 1969.

- Kendrick, Walter M. (1987). The Secret Museum Pornography in Modern Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20729-5.

- Lane, Frederick S. (2000). Obscene Profits The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92096-4.

- Sutherland, John (1983). Offensive Literature Decensorship in Britain, 1960–1982. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-389-20354-4.

- Cleland, John (1985). Fanny Hill Or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-043249-7.

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fanny Hill. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure at Project Gutenberg

- Charles Dickens's Themes A surprising allusion to Fanny Hill in Dombey and Son.

- BBC TV Adaptation First Broadcast October 2007