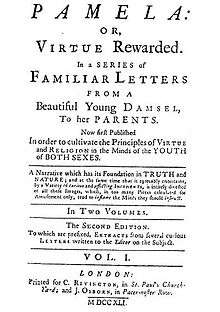

Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded

Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson, a novel which was first published in 1740. Considered the first true English novel, it serves as Richardson's version of conduct literature about marriage. Pamela tells the story of a fifteen-year-old maidservant named Pamela Andrews, whose employer, Mr. B, a wealthy landowner, makes unwanted and inappropriate advances towards her after the death of his mother. Pamela strives to reconcile her strong religious training with her desire for the approval of her employer in a series of letters and, later in the novel, journal entries all addressed to her impoverished parents. After various unsuccessful attempts at seduction, a series of sexual assaults, and an extended period of kidnapping, the rakish Mr. B eventually reforms and makes Pamela a sincere proposal of marriage. In the novel's second part Pamela marries Mr. B and tries to acclimatize to her new position in upper-class society. The full title, Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded, makes plain Richardson's moral purpose. A best-seller of its time, Pamela was widely read but was also criticized for its perceived licentiousness and disregard for class barriers.

Richardson's Pamela (1740–41) | |

| Author | Samuel Richardson |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Epistolary novel Psychological |

| Publisher | Messrs Rivington & Osborn |

Publication date | 1740 |

Two years after the publication of Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded, Richardson published a sequel, Pamela in her Exalted Condition (1742). He revisited the theme of the rake in his Clarissa (1748), and sought to create a "male Pamela" in Sir Charles Grandison (1753).

Since Ian Watt discussed it in The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding in 1957, literary critics and historians have generally agreed that Pamela played a critical role in the development of the novel in English.[1]

Plot summary

Volume 1

Pamela Andrews is a pious, innocent fifteen-year-old who works as Lady B's maidservant in Bedfordshire. The novel starts after Lady B has died, when her son, the squire Mr. B, begins to pay Pamela more attention, first giving her his mother's clothes, then trying to seduce her in the Summer House. When he wants to pay her to keep his failed attempt at seduction a secret, she refuses and tells Mrs. Jervis, the housekeeper, her best friend at the house. Undaunted, he hides in her closet and pops out and tries to kiss her as she undresses for bed. Pamela debates returning to her impoverished parents to preserve her innocence, but remains undecided.

Mr. B claims that he plans to marry her to Mr. Williams, his chaplain in Lincolnshire, and gives money to her parents in case she will let him take advantage of her. She refuses and decides to go back to her parents, but Mr. B intercepts her letters to her parents and tells them that she is having a love affair with a poor clergyman and that he will send her to a safe place to preserve her honor. Pamela is then driven to Lincolnshire Estate and begins a journal, hoping it will be sent to her parents one day. The Lincolnshire Estate housekeeper, Mrs. Jewkes, is no Mrs. Jervis. She is a rude, "odious"[2], "unwomanly" woman who is devoted to Mr. B; Pamela suspects that she might even be "an atheist!". Mrs. Jewkes constrains Pamela to be her bedfellow. Mr. B promises that he won't approach her without her leave, and then in fact stays away from Lincolnshire for a long time.

Pamela meets Mr. Williams and they agree to communicate by putting letters under a sunflower in the garden. Mrs. Jewkes continues to maltreat Pamela, even beating her after she calls her a "Jezebel". Mr. Williams asks the village gentry for help; though they pity Pamela, none will help her because of Mr. B's social position. Sir Simon even argues that no one will hurt her, and no family name will be tarnished since Pamela belongs to the poor Andrews family. Mr. Williams proposes marriage to her to escape Mr. B's wickedness.

Mr. Williams is attacked and beaten by robbers. Pamela wants to escape when Mrs. Jewkes is away, but is terrified by two nearby cows that she thinks are bulls. Mr. Williams accidentally reveals his correspondence with Pamela to Mrs. Jewkes; Mr. B jealously says that he hates Pamela, as he has claimed before. He has Mr. Williams arrested and plots to marry Pamela to one of his servants. Desperate, Pamela thinks of running away and making them believe she has drowned in the pond. She tries unsuccessfully to climb a wall, and, when she is injured, she gives up.

Mr. B returns and sends Pamela a list of articles that would rule their partnership; she refuses because it means she would be his mistress. With Mrs. Jewkes' complicity, Mr. B gets into bed with Pamela disguised as the housemaid Nan, but, when Pamela falls into a fit and seems likely to die, he seems to repent and is kinder in his seduction attempts. She implores him to stop altogether. In the garden he implicitly says he loves her but can't marry her because of the social gap.

Volume 2

A gypsy fortuneteller approaches Pamela and passes her a bit of paper warning her against a sham-marriage. Pamela has hidden a parcel of letters under a rosebush; Mrs. Jewkes seizes them and gives them to Mr. B, who then feels pity for what he has put her through and decides to marry her. She still doubts him and begs him to let her return to her parents. He is vexed but lets her go. She feels strangely sad when she bids him goodbye. On her way home he sends her a letter wishing her a good life; moved, she realises she is in love. When she receives a second note asking her to come back because he is ill, she accepts.

Pamela and Mr. B talk of their future as husband and wife and she agrees with everything he says. She explains why she doubted him. This is the end of her trials: she is more submissive to him and owes him everything now as a wife. Mr. Williams is released. Neighbours come to the estate and all admire Pamela. Pamela's father comes to take her away but he is reassured when he sees Pamela happy.

Finally, she marries Mr. B in the chapel. But when Mr. B has gone to see a sick man, his sister Lady Davers comes to threaten Pamela and considers her not really married. Pamela escapes by the window and goes in Colbrand's chariot to be taken away to Mr. B. The following day, Lady Davers enters their room without permission and insults Pamela. Mr. B, furious, wants to renounce his sister, but Pamela wants to reconcile them. Lady Davers, still contemptuous towards Pamela, mentions Sally Godfrey, a girl Mr. B seduced in his youth, now mother of his child. He is cross with Pamela because she dared approach him when he was in a temper.

Lady Davers accepts Pamela. Mr. B explains to Pamela what he expects of his wife. They go back to Bedfordshire. Pamela rewards the good servants with money and forgives John, who betrayed her. They visit a farmhouse where they meet Mr. B's daughter and learn that her mother is now happily married in Jamaica; Pamela proposes taking the girl home with them. The neighbourhood gentry who once despised Pamela now praise her.

Characters

- Pamela Andrews: The novel's fifteen-year-old pious, naïve protagonist who narrates the novel. She is passed on by her former employer to her son, Mr. B, who puts her through numerous sexual advances and even assault before she eventually falls for and marries him.

- John and Elizabeth Andrews: Pamela's father and mother to whom Pamela's letters are addressed. Pamela only hears from her father and is the only one of her parents to appear physically in the novel.

- Mr. Williams: Pamela's pastor who helps her escape Mr. B's estate and deliver letters to her family. He offers to marry Pamela to secure her from Mr. B's unwanted advances, but she denies him and when Mr. B finds out he has Williams taken away to debtors prison.

- Mr. B: Pamela's lascivious and abusive employer who falls in love with, and eventually marries her.

- Lady B: Mr. B's and Lady Daver's mother; Pamela's former employer.

- Lady Davers: Mr. B's sister. She initially disapproves of Pamela's union with Mr. B for her lower class, but eventually warms to the modest girl.

- Mrs. Jervis: The elderly housekeeper of Mr. B's Bedfordshire estate. She becomes one of Pamela's best friends, as stated in a letter to her parents. Despite her good intentions, she is nearly useless in preventing Mr. B's unwanted advances on Pamela.

- Mrs. Jewkes: The housekeeper of Mr. B's Lincolnshire estate. She holds Pamela at the estate according to Mr. B's wishes and is completely dutiful to him. She warms to Pamela once she marries Mr. B.

- Sally Godfrey: Mr. B's mistress from his college days. Has a daughter by Mr. B, but took off to Jamaica and got married.

- Monsieur Colbrand: Helps in keeping Pamela at the Lincolnshire estate but proves to be protecting her, and helps her escape from Lady Davers.

- Miss Goodwin: The daughter of Mr. B and Sally Godfrey. Become's Pamela's stepdaughter, lives in Jamaica with her mother.

Genre

Conduct books and the novel

Richardson began writing Pamela after he was approached by two book sellers who requested that he make them a book of letter templates. Richardson accepted the request, but only if the letters had a moral purpose. As Richardson was writing the series of letters turned into a story. [3] Writing in a new form, the novel, Richardson attempted to both instruct and entertain. Richardson wrote Pamela as a conduct book, a sort of manual which codified social and domestic behavior of men, women, and servants, as well as a narrative in order to provide a more morally concerned literature option for young audiences. Ironically, some readers focused more upon the bawdy details of Richardson's novel, resulting in some negative reactions and even a slew of literature satirizing Pamela, and so he published a clarification in the form of A Collection of the Moral and Instructive Sentiments, Maxims, Cautions, and Reflexions, Contained in the Histories of Pamela, Clarissa, and Sir Charles Grandison in 1755. [4] Many novels, from the mid-18th century and well into the 19th, followed Richardson's lead and claimed legitimacy through the ability to teach as well as amuse.

Epistolary

Epistolary novels—novels written as series of letters—were extremely popular during the 18th century. Fictional epistolary narratives originated in their early form in 16th-century England; however, they acquired wider renown with the publication of Richardson's Pamela.[5] Richardson and other novelists of his time argued that the epistolary form allowed the reader greater access to a character's thoughts. Richardson stressed in his preface to The History of Sir Charles Grandison that the form permitted the immediacy of "writing to the moment":[6] that is, Pamela's thoughts were recorded nearly simultaneously with her actions.

In the novel, Pamela writes two kinds of letters. At the beginning, while she decides how long to stay on at Mr. B's after his mother's death, she tells her parents about her various moral dilemmas and asks for their advice. After Mr. B. abducts her and imprisons her in his country house, she continues to write to her parents, but since she does not know if they will ever receive her letters, the writings are also considered a diary.

In Pamela, the letters are almost exclusively written by the heroine, restricting the reader's access to the other characters; we see only Pamela's perception of them. This makes the reader to see Pamela's character development over the duration of the novel.[7] In Richardson's other novels, Clarissa (1748) and The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753), the reader is privy to the letters of several characters and can more effectively evaluate the characters' motivations and moral values.

Literary significance and criticism

Reception

Considered by many literary experts as the first English novel, Pamela was the best-seller of its time. It was read by countless buyers of the novel and was also read in groups. An anecdote which has been repeated in varying forms since 1777 described the novel's reception in an English village: "The blacksmith of the village had got hold of Richardson's novel of Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded, and used to read it aloud in the long summer evenings, seated on his anvil, and never failed to have a large and attentive audience.... At length, when the happy turn of fortune arrived, which brings the hero and heroine together, and sets them living long and happily... the congregation were so delighted as to raise a great shout, and procuring the church keys, actually set the parish bells ringing."[8]

The novel was also integrated into sermons as an exemplar. It was even an early “multimedia” event, producing Pamela-themed cultural artefacts such as prints, paintings, waxworks, a fan, and a set of playing cards decorated with lines from Richardson's works.[9]

Given the lax copyright laws at the time, many "unofficial" sequels were written and published without Richardson's consent, for example, Pamela's conduct in high life published 1741, sometimes attributed to John Kelly (1680?–1751). There were also several satires, the most famous being An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews by Henry Fielding, published under the pseudonym "Mr. Conny Keyber". Shamela portrays the protagonist as an amoral social climber who attempts to seduce "Squire Booby" while feigning innocence to manipulate him into marrying her. In this version, the author works to invalidate Pamela by pointing out the incongruities between characters and the overall plot of the story. This version suggests that she was not really as virtuous as she may have seemed to be.[10] Another important satire was The Anti-Pamela; or Feign’d Innocence Detected (1741) by Eliza Haywood. Although not technically a satire, the Marquis de Sade's Justine is generally perceived as a critical response to Pamela, due in part to its subtitle, "The Misfortunes of Virtue".

At least one modern critic has stated that the rash of satires can be viewed as a conservative reaction to a novel that called class, social and gender roles into question[11] by asserting that domestic order can be determined not only by socio-economic status but also by moral qualities of mind.

Richardson's revisions

The popularity of Richardson's novel led to much public debate over its message and style. Richardson was of the artisanal class, and among England's middle and upper classes, where the novel was popular, there was some displeasure over its at times plebeian style. Apparently certain ladies of distinction took exception to the ways in which their fictional counterparts were represented. Richardson responded to some of these criticisms by revising the novel for each new edition; he also created a "reading group" of such women to advise him. Some of the most significant changes he made were alterations to Pamela's vocabulary: in the first edition her diction is that of a labouring-class woman, but in later editions Richardson made her more linguistically middle-class by removing the working-class idioms from her speech. In this way, he made her marriage to Mr. B less scandalous as she appeared to be more his equal in education. The greatest change was to have her his equal too in birth—by revising the story to reveal her parents as reduced gentlefolks. In the end Richardson revised and released fourteen editions of Pamela, the last of which was published in 1801 after his death.[12]

Original sources

A publication, Memoirs of Lady H, the Celebrated Pamela (1741), claims that the inspiration for Richardson's Pamela was the marriage of a coachman's daughter, Hannah Sturges, to the baronet, Sir Arthur Hesilrige, in 1725. Samuel Richardson claimed that the story was based on a true incident related to him by a friend about 25 years before, but did not identify the principals.[13]

Shirin and Pamela

Pamela has significant similarities to the famous Persian tragic romance of Khosrow and Shirin by the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi. In both tales a rich, famous, and hedonistic man is trying to seduce the main female character of the story. Even though the female character is truly in love with the male counterpart, she resists his seductions and requests a proper marriage. At the end the male character gives in to an official marriage with the woman he loves and this love causes a gradual and positive change in the male character. The moral of both stories is the triumph of patience, virtue and modesty over despotism and hedonism.[14]

Feminism in Pamela

Some believe that Richardson was one of the first male writers to take a feminist view while writing a novel.[15] Pamela has been described as being a feminist piece of literature because it rejects traditional views of women and supports the new and changing role of women in society. One of the ways in which feminism is shown in the text is through allowing readers to see the depths of women (i.e. their emotions, feelings, thoughts) rather than seeing women at surface level.[16] The letters allow readers to see how Pamela feels about the events occurring in her life and how she chooses to handle these events. She is seen as an independent intellectual who can think for herself rather than a working housewife who depends completely on her husband.

Criticism

- Armstrong, Nancy. Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Blanchard, Jane. “Composing Purpose in Richardson's ‘Pamela.’” South Atlantic Review, vol. 76, no. 2, 2011, pp. 93–107. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43050924.

- Conboy, Sheila C. “Fabric and Fabrication in Richardson's Pamela.” ELH, vol. 54, no. 1, 1987, pp. 81–96. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2873051.

- Doody, Margaret Anne. A Natural Passion: A Study of the Novels of Samuel Richardson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974.

- Dussinger, John A. ""Ciceronian Eloquence": The Politics of Virtue in Richardson's Pamela." Eighteenth Century Fiction, vol. 12, no. 1, 1999, pp. 39–60. University of Toronto Press. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/ecf.1999.0019.

- Flynn, Carol Houlihan. "Horrid Romancing: Richardson’s Use of the Fairy Tale." In Samuel Richardson: A Man of Letters, 145-95. Princeton University Press, 1982. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7zvgnr.8.

- Gwilliam, Tassie. “Pamela and the Duplicitous Body of Femininity.” Representations, no. 34. 1991, pp. 104–33. University of California Press. JSTOR 2928772.

- Keymer, Tom; Sabor, Peter (2005), Pamela in the Marketplace: literary controversy and print culture in eighteenth-century Britain and Ireland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521813372.

- Levin, Gerald. “Richardson's ‘Pamela’: ‘Conflicting Trends.’” American Imago, vol. 28, no. 4, 1971, pp. 319–329. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26302663.

- McKeon, Michael. The Origins of the English Novel: 1600–1740. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Rivero, Albert J. “The Place of Sally Godfrey in Richardson’s Pamela.” Passion and Virtue: Essays on the Novels of Samuel Richardson, edited by David Blewett, University of Toronto Press, 2001, pp. 52–72. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442678293.9.

- Rogers, Katharine M. “Sensitive Feminism vs. Conventional Sympathy: Richardson and Fielding on Women.” NOVEL; A Forum on Fiction, vol. 9, no. 3., 1976, pp. 256–70. Duke University Press. JSTOR 1345466

- Townsend, Alex, Autonomous Voices: An Exploration of Polyphony in the Novels of Samuel Richardson, 2003, Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt/M., New York, Wien, 2003, ISBN 978-3-906769-80-6, 978-0-8204-5917-2

- Vallone, Lynne. "“The Matter of Letters”: Conduct, Anatomy, and Pamela." In Disciplines of Virtue: Girls` Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, 26-44. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1995. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt211qw91.6.

- Watt, Ian. The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957.

Adaptations

Paintings

Around 1742 Francis Hayman also produced two paintings drawing on scenes and themes from the novel for supper boxes 12 and 16 at Vauxhall Gardens. The painting for Box 12 is now lost but showed the departure scene from Letter XXIX, whilst the one for Box 16 shows Pamela fleeing to Mr B.'s coach after revealing her marriage to Lady Davers and Mr B.'s servant Colbrand forcibly defending her from two of Lady Davers' servants.[17] The latter was bought from the Gardens in 1841 by William Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale, whose heirs sold it in 1947 to Henry Hornyold-Strickland, who in turn donated it to the National Trust as part of the house, collections and gardens of Sizergh Castle in 1950.[18]

Soon afterwards, in 1743, Joseph Highmore produced a series of twelve paintings as the basis for a set of engravings. They are a free adaptation of the novel, mainly focusing on the first book. They are now equally divided between Tate Britain, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Fitzwilliam Museum, each of which has four of the series.

Stage

Its success also led to several stage adaptations in France and Italy. In Italy, it was adapted by Chiari and Goldoni. In France, Boissy put on a Paméla ou la Vertu mieux éprouvée, a verse comedy in three acts (Comédiens italiens ordinaires du Roi, 4 March 1743), followed Neufchâteau's five-act verse comedy Paméla ou la Vertu récompensée (Comédiens Français, 1 August 1793). Appearing during the French Revolution, Neufchâteau's adaptation was felt to be too Royalist in its sympathies by the Committee of Public Safety, which imprisoned its author and cast (including Anne Françoise Elisabeth Lange and Dazincourt) in the Madelonnettes and Sainte-Pélagie prisons. Mademoiselle Lange's straw hat from the play launched a trend for Pamela hats and bonnets which were worn well into the second half of the nineteenth century.[19][20][21]

Pamela was also the basis for the libretto of Niccolò Piccinni's comic opera La buona figliuola.

Playwright Martin Crimp uses the text as a "provocation" for his stage play When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other: 12 Variations on Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, opening at the Royal National Theatre in 2019 starring Cate Blanchett and Stephen Dillane directed by Katie Mitchell.[22]

Novels

The success of Pamela soon led to its translation into other languages, most notably into French by abbé Prévost. It was also imitated by Robert-Martin Lesuire in his own novel la Paméla française, ou Lettres d’une jeune paysanne et d’un jeune ci-devant, contenant leurs aventures. More recently, Bay Area author Pamela Lu's first book Pamela: A Novel evokes Richardson's title and also borrows from Richardson the conceit of single-letter names to create a very different type of "quasi-bildungsroman," according to Publisher's Weekly.[23]

Film and TV

- 1974 – UK movie by Jim O'Connolly: Mistress Pamela[24] with Ann Michelle as Pamela Andrews and Julian Barnes as Lord Robert Devenish (Mr. B).

- 2003 – Italian TV series by Cinzia TH Torrini: Elisa di Rivombrosa[25]

The popular TV series (26 episodes) Elisa di Rivombrosa is loosely based on Pamela. The story takes place in the second half of the 18th century in Turin (Italy). The role of Pamela is that of Elisa Scalzi (played by Vittoria Puccini) in the series. The role of Mr. B is that of Count Fabrizio Ristori (played by Alessandro Preziosi).[26]

Allusions/references from other works

- Brontë, Charlotte (1847), Jane Eyre: Jane mentions Bessie's nursery stories and how some of them came from Pamela.

- Jackson, Shirley (1959), The Haunting of Hill House: The character of Doctor Montague mentions several times that he is reading Pamela.

- Freedland, Jonathan (9 January 2007), The Long View (video), UK: BBC Radio 4. On 9 January 2007, BBC Radio 4 broadcast The Long View which contrasted Pamela's effect on 18th-century society with that of video games on 20th-century society.

- Amis, Kingsley (1960), Take a Girl Like You: Some have viewed this novel to be a modern retelling of Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded as it shares many key elements with the novel, such as a young, beautiful woman being taken by an arrogant man. However, Amis claimed afterwards that he had little interest in classic fiction, which makes this proposition less likely.

- Baker, Jo (2013), Longbourn: Both volumes of Pamela have been read by Elizabeth Bennet and she passes the books to one of the maids. The maid contemplates the behavior of the characters and wonders what her own conduct would be if put in the same position.

- Gabaldon, Diana (1993), Voyager, the third novel in the Outlander series: In the chapter "The Torremolinos Gambit", the characters Jamie Fraser and Lord John Grey discuss Samuel Richardson's immense novel Pamela. Another mention is made in The Fiery Cross, Gabaldon's fifth novel in the series, wherein Roger Wakefield is perusing the Fraser library and comes across the "monstrous" "gigantic" novel with several bookmarks delineating where various readers gave up on the novel, either temporarily or permanently.

- O'Brian, Patrick (1979), The Fortune of War: The character Captain York recommends the novel Pamela to his dinner guests.

- Heyer, Georgette (1956), Sprig Muslin: Amanda, attempting to pass herself off as a lady's maid, uses Pamela as inspiration to invent a story that she was fired from her previous position because her employer had made improper advances towards her.

Footnotes

- Watt, Ian (1957). The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Richardson, Samuel, 1689-1761. (2001). Pamela, or, Virtue rewarded. Keymer, Thomas, 1962-, Wakely, Alice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282960-2. OCLC 46641908.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Doody, Margaret (21 June 2018). "An introduction to Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded". The British Library. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Vallone, Lynne (26 April 1995). Disciplines of Virtue: Girls' Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt211qw91.6. ISBN 978-0-300-23927-0. JSTOR j.ctt211qw91.

- Traversa, Vincenzo (2005), transl. Traversa, Vincenzo. Three Italian Epistolary Novels: Foscolo, De Meis, Piovene : Translations, Introductions, and Backgrounds, p. xii. Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Sage, Lorna, et al., eds. (1999). The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English, p. 224. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- Flynn, Carol. Samuel Richardson: A Man of Letters. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Fysh, Stephanie (1997). The Work(s) of Samuel Richardson, p. 60. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-626-1, 978-0-87413-626-5.

- Fysh (1997), p. 58.

- Johnson, Maurice (1961). "The Art of Parody: Shamela". Literature Criticisms from 1400–1800. 85: 19–45 – via Literature Resource Center.

- Keymer; Sabor (2005), Pamela in the Marketplace, p. 5, ISBN 978-0521813372.

- Bender, Ashley. "Samuel Richardson's Revisions of Pamela". ProQuest 305167953. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Keymer, Thomas, and Sabor, Peter (2005). Pamela in the Marketplace: Literary Controversy and Print Culture in Eighteenth-Century Britain and Ireland, pp. 100–02. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- نصراصفهانی,محمدرضا; حقی,مریم (4 January 1389). "شیرین و پاملا (بررسی تطبیقی "خسرو و شیرین" نظامی و "پاملا"ی ساموئل ریچاردسون)". 1 (8). Retrieved 12 August 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rogers, Katharine (1976). "Sensitive Feminism vs. Conventional Sympathy: Richardson and Fielding on Women". Novel. 9 (3): 256–70. doi:10.2307/1345466. JSTOR 1345466.

- Gwilliam, Tassie (1991). "Pamela and the Duplicitous Body of Femininity". Representations. 34: 104–33. doi:10.1525/rep.1991.34.1.99p00502.

- Leigh G. Dillar, 'Drawing Outside the Book – Parallel Illustration and the Creation of a Visual Culture', in Ionescu, Christina (2015). Book Illustration in the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 237–40. ISBN 978-1443873093. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "The Elopement". National Trust. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Muret, Théodor (September 1865). Ainsworth, William Harrison (ed.). "Politics on the Stage". The New Monthly Magazine. 135: 114–15.

- "Pamela bonnet". Berg Fashion Library. Bloomsbury. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Cunnington, C. Willett (1937). English women's clothing in the nineteenth century (1990 reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications. p. 302. ISBN 978-0486319636.

- "When We Have Sufficiently Tortured Each Other". National Theatre. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- "Pamela A Novel".

- "Mistress Pamela". 1 January 1974 – via IMDb.

- "Elisa di Rivombrosa". 17 December 2003 – via IMDb.

- "Alessandro Preziosi".

References

- Richardson, Samuel (1740). Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1st ed.). London: Messrs Rivington & Osborn.

- Doody, Margaret Ann (1995). Introduction to Samuel Richardson's Pamela. Viking Press.

Bibliography

- Editions

- Richardson, Samuel Pamela (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2003) ISBN 978-0140431407. Edited by Margaret Ann Doody and Peter Sabor. This edition takes as its copy-text the revised, posthumously published edition of 1801.

- — (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008) ISBN 978-0199536498. Edited by Thomas Keymer and Alice Wakely. This edition takes as its copy-text the first edition of November 1740 (dated 1741).

- Richardson, Samuel Pamela Or Virtue Rewarded (Lector House, 2019) ISBN 935-3366712.

External links

![]()

- Complete text at Project Gutenberg

- Illustration History of Samuel Richardson's Pamela