FNR regulon

The fnr (fumarate and nitrate reductase) gene of Escherichia coli encodes a transcriptional activator (FNR) which is required for the expression of a number of genes involved in anaerobic respiratory pathways. The FNR (Fumarate and Nitrate reductase Regulatory) protein of E. coli is an oxygen – responsive transcriptional regulator required for the switch from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism.

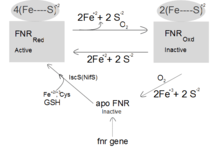

The fnr gene is expressed under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions and is subject to autoregulation and repression by glucose, particularly during anaerobic growth. The functional state of FNR is determined by a (rapid) inactivation of FNR by O2, and a slow (constant) reactivation with glutathione as the reducing agent.[1]

Regulation of FNR by oxygen

Only if neither O2 nor nitrate are available, fumarate reductase and the fermentative enzymes are synthesized. The switch from aerobic to nitrate and fumarate respiration or fermentation corresponds to a progressive decrease in ATP yields. This regulation ensures preferential use of electron acceptors with high ATP yields, and is effected by regulators responding to O2, nitrate and fumarate.

Presence of oxygen

The sensory domain of FNR contains a Fe-S cluster, which is of the [4Fe-4S]2+ type under anaerobic conditions. Oxygen is supplied to the cytoplasmic FNR by diffusion and inactivates FNR by direct interaction. The Fe-S cluster is converted to [3Fe-4S]+ or a [2Fe-4S]+ by oxygen, resulting in FNR inactivation. After prolonged incubation with oxygen, the Fe-S cluster is destroyed by conversion to [2Fe-2S] cluster and finally to apoFNR.

Absence of oxygen

Interconversion of active and inactive FNR is a reversible process. The oxygen-sensing domain of FNR contains a surface-exposed Fe-S cluster, which can react with cellular reductants, such as glutathione or thiol proteins. The IscS isoenzyme (iscS gene) is one of the most important requirements for formation of [4Fe–4S].FNR in vivo.[2] The formation of [4Fe–4S] FNR from apoFNR is part of de novo synthesis of active FNR. The reaction requires cysteine desulphurase which catalyzes desulphuration of the cysteine providing HS- (presumably via enzyme bound persulphide) for the FeS cluster formation. Whether glutathione supports also the conversion of [2Fe–2S].FNR to [4Fe–4S].FNR is not known. Under anoxic conditions, the [4Fe-4S].FNR, bound to 4 cysteine residues binds to DNA target sites, and controls the expression of corresponding genes.

Oxygen is the actual signal for FNR whereas; reduction serves as a constant reversal of FNR to the active state. However, the inactivation of FNR requires only an oxidizing agent, and not necessarily oxygen itself. Ferricyanide is able, in vivo and in vitro, to promote inactivation of FNR function or [4Fe–4S].FNR destruction by means of oxidizing the cluster.[3]

Genes regulated by FNR

FNR represents the master-switch which ensures that aerobic respiration is used in preference to anaerobic respiratory metabolism or fermentation, simply because important anaerobic genes are not expressed unless FNR is in its active (anaerobic) form. FNR is a very important transcriptional factor that is involved in the regulation of synthesis of many genes.[4] Important groups of FNR-regulated genes of E. coli

| Function of gene products | Example |

|---|---|

| Respiratory enzymes | anoxic, oxic Fumarate reductase (frdABCD) |

| Transmembrane carriers | Nitrite efflux (narK ) |

| Anaerobic catabolism | fermentation Pyruvate formate-lyase (pflA) |

| Gene regulators | ArcA, FNR, (NarX) |

.png)

Active FNR protein activates and represses target genes in response to anaerobiosis. It also represses the aerobic genes, cytochrome d and o oxidase, and NADH dehydrogenase II. It acts as a positive regulator of genes expressed under anaerobic fermentative conditions such as aspartase, formate hydrogenase, fumarate reductase, and pyruvate formate lyase.[5]

Regulation of ArcA system

Arc A is regulated by FNR in anaerobic conditions. Anaerobic activation of arcA transcription is increased three- to fourfold in the presence of Fnr. The arcA upstream regulatory region contains five putative promoter sequences and a putative Fnr-binding site. Identification of the transcription start sites indicates that transcription occurs in aerobiosis from three constitutive upstream promoters (Pe, Pd, Pc). In anaerobiosis an additional completely Fnr-dependent transcript starting at Pa, is present. Both of these genes then negatively regulate the sodA gene, coding for manganese superoxide dismutase.[6]

Regulation of NarX/NarL system

The fnr gene product, a pleiotropic transcriptional activator, is required for expression of the operons that encode nitrate and fumarate reductase complexes. FNR, an efficient respiratory oxidant induces synthesis of nitrate respiratory enzymes and simultaneously represses synthesis of enzymes for respiring the lower-potential acceptors.

In Escherichia coli, the anaerobic expression of genes encoding the nitrate (narGHJI) and dimethyl sulphoxide (dmsABC) terminal reductases is stimulated by the global anaerobic regulator- FNR. The ability of FNR to activate transcription initiation has been proposed to be dependent on protein–protein interactions between RNA polymerase and two activating regions (AR) of FNR, FNR-AR1 and FNR-AR3. Also, in the presence of activated narL, the effect of FNR binding to the RNAP is decreased greatly.[7]

Eukaryotic system having a homologue to FNR

In Fusarium oxysporum, a member of the fungi family, contains a unique cytochrome P-450, whose genes when sequenced, exhibited the same sequence as the binding site of FNR, a DNA-binding, O2 -sensor protein that positively regulates expressions of hypoxic sites in E. coli. These results raise the interesting possibility that the expression of the fungal denitrification system is also regulated, by a set of mechanisms, i.e., a combination of an FNR-like system and a system responding to nitrate/ nitrite.[8]

References

- The oxygen responsive transcriptional regulator FNR of Escherichia coli:the search for signals and reactions:Gottfried Unden; Jan Schirawski. Molecular Microbiology 25: 205-210. 1997.

- The cysteine desulfurase, IscS, has a major role in in vivo Fe-S cluster formation in Escherichia coli.Schwartz et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.97. 2000

- Control of FNR Function of Escherichia coli by O2 and Reducing Conditions: G. Unden, S. Achebach, G. Holighaus, H.-Q. Tran, B. Wackwitz and Y. Zeuner. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:263-268. 2002.

- A Reassessment of the FNR Regulon and Transcriptomic Analysis of the Effects of Nitrate, Nitrite, NarXL, and NarQP as Escherichia coli K12 Adapts from Aerobic to Anaerobic Growth: Chrystala Constantinidou, Jon L. Hobman, Lesley Griffiths, Mala D. Patel, Charles W. Penn, Jeffrey A. Cole, and Tim W. Overton. THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY. 281:4802–4815. 2006.

- Oxygen-regulated gene expression in Escherichia coli:The 1992 Marjory Stephenson Prize Lecture, JOHN R. GUEST. Journal of General Microbiology. 138, 2253-2263. 1992

- Anaerobic activation of arcA transcription in Escherichia coli: roles of Fnr and ArcA: Inès Company, Danlèle Touati. Molecular Microbiology. 11: 955–964. 1994.

- FNR-dependent activation of the class II dmsA and narG promoters ofEscherichia coli requires FNR-activating regions 1 and 3 - Karin E. Lamberg, Patricia J. Kiley

- Nitric Oxide Reductase Cytochrome P-450 gene, CYP 55, of the fungus Fusarium oxysporum Containing a Potential Binding Site for FNR, the transcription factor involved in the regulation of Anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli: Daisuke Tomura, Enji Obika, Kiyoshi Fukamizu and Irofumi Shoun. The Journal of Biochemistry. 116:88-94. 1994.