Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collections and publishes academic journals and books on plant and animal biology. The society also awards a number of prestigious medals and prizes.

| |

| Formation | 1788 (royal charter: 1802) |

|---|---|

| Type | Learned society |

| Purpose | Natural History, Evolution & Taxonomy |

| Location | |

Membership | 2,921[1] |

President | Sandra Knapp |

| Website | www |

| Remarks | Motto: Naturae Discere Mores (To Learn the Ways of Nature) |

A product of the 18th-century enlightenment, the Society is the oldest extant biological society in the world, and is historically important as the venue for the first public presentation of the theory of evolution on 1 July 1858.

The patron of the society is Queen Elizabeth II. Honorary members include Emeritus Emperor Akihito of Japan, King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden (both of whom have active interests in natural history), and the eminent naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough.[2]

History

.jpg)

The Linnean Society was founded in 1788 by botanist Sir James Edward Smith. The society takes its name from the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus, the 'father of taxonomy', who systematised biological classification through his binomial nomenclature. He was known as Carl von Linné after his ennoblement, hence the spelling 'Linnean', rather than 'Linnaean'. The society had a number of minor name variations before it gained its Royal Charter on 26 March 1802, when the name became fixed as "The Linnean Society of London". In 1802, as a newly incorporated society, it comprised 228 fellows. It is the oldest extant natural history society in the world.[3] Throughout its history the society has been a non-political and non-sectarian institution, existing solely for the furtherance of natural history.[4]

The inception of the society was the direct result of the purchase by Sir James Edward Smith of the specimen, book and correspondence collections of Carl Linnaeus. When the collection was offered for sale by Linnaeus's heirs, Smith was urged to acquire it by Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent botanist and President of the Royal Society. Five years after this purchase Banks gave Smith his full support in founding the Linnean Society, and became one of its first Honorary Members.[5]

The society has numbered many prominent scientists amongst its fellows. One such was the botanist Robert Brown, who was Librarian, and later President (1849-1853); he named the cell nucleus and discovered Brownian motion.[6] In 1854 Charles Darwin was elected a fellow; he is undoubtedly the most illustrious scientist ever to appear on the membership rolls of the society.[7] Another famous fellow was biologist Thomas Huxley, who would later gain the nickname "Darwin's bulldog" for his outspoken defence of Darwin and evolution. Men notable in other walks of life have also been fellows of the society, including the physician Edward Jenner, pioneer of vaccination, the Arctic explorers Sir John Franklin and Sir James Clark Ross, colonial administrator and founder of Singapore, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles and Prime Minister of Britain, Lord Aberdeen.[8]

Since 1857 the society has been based at Burlington House, Piccadilly, London; an address it shares with a number of other learned societies: the Geological Society of London, the Royal Astronomical Society, the Society of Antiquaries of London and the Royal Society of Chemistry.[9]

The first public exposition of the 'Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection', arguably the greatest single leap of progress made in biology, was presented to a meeting of the Linnean Society on 1 July 1858. At this meeting a joint presentation of papers by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace was made, sponsored by Joseph Hooker and Charles Lyell as neither author could be present.[10]

In 1904 the society elected its first female fellows, following a number of years of tireless campaigning by the botanist Marian Farquharson. Whilst the society's council was reluctant to admit women, the wider fellowship was more supportive; only 17% voted against the proposal. Among the first to benefit from this were the ornithologist and photographer Emma Louisa Turner, Lilian J. Veley, a microbiologist and Annie Lorrain Smith, a lichenologist and mycologist, all formally admitted on 19 January 1905.[11] Also numbered in the first cohort of women to be elected in 1904, was the paleobotanist, and later pioneer of family planning, Marie Stopes, and the philanthropist Constance Sladen, founder of the Percy Sladen Memorial Trust.[12][13]

The society's connection with evolution remained strong into the 20th century. Sir Edward Poulton, who was President 1912-1916, was a great defender of natural selection, and was the first biologist to recognise the importance of frequency-dependent selection.[14][15]

In April 1939 the threat of war obliged the society to relocate the Linnean collections out of London to Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire, where they remained for the duration of World War II. This move was facilitated by the 12th Duke of Bedford, a Fellow of the Linnean Society himself. Three thousand of the most precious items from the library collections were packed up and evacuated to Oxford; the country house of librarian Warren Royal Dawson provided a refuge for the society's records.[16]

The first female President of the society was Irene Manton (1973 to 1976), who pioneered the biological use of electron microscopy. Her work revealed the structure of the flagellum and cilia, which are central to many systems of cellular motility.[17][18]

Recent years have seen an increased interest within the society in issues of biodiversity conservation. This was highlighted by the inception in 2015 of an annual award, the John Spedan Lewis Medal, specifically honouring persons making significant and innovative contributions to conservation.[19]

Membership

Fellowship requires nomination by at least one fellow, and election by a minimum of two thirds of those electors voting. Fellows may employ the post-nominal letters 'FLS'. Fellowship is open to both professional scientists and to amateur naturalists who have shown active interest in natural history and allied disciplines. Having authored relevant publications is an advantage, but not a necessity, for election. Following election, new fellows must be formally admitted, in person at a meeting of the society, before they are able to vote in society elections. Admission takes the form of signing the membership book, and thereby agreeing to an obligation to abide by the statutes of the society. Following this the new fellow is taken by the hand by the president, who recites a formula of admission to the fellowship. Other forms of membership exist: 'Associate', for supporters of the society who do not wish to submit to the formal election process for fellowship, and 'Student Associate', for those registered as students at a place of tertiary education. Associate members may apply for election to the fellowship at any time. Finally, there are three types of membership that are prestigious and strictly limited in number: 'Fellow honoris causa', 'Foreign', and lastly, 'Honorary'. These forms of membership are bestowed following election by the fellowship at the annual Anniversary Meeting in May.[20][21]

Meetings

Meetings have historically been, and continue to be, the main justification for the society's existence. Meetings are venues for people of like interests to exchange information, talk about scientific and literary concerns, exhibit specimens, and listen to lectures. Today, meetings are held in the evening and also at lunchtime. Most are open to the general public as well as to members, and the majority are offered without charge for admission.[22]

On or near the 24th of May, traditionally regarded as the birthday of Carl Linnaeus, the Anniversary Meeting is held. This is for fellows and guests only, and includes ballots for membership of the council of the society and the awarding of medals.[23] On May 22nd 2020, for the first time in its history, the Anniversary Meeting was held online via videotelephony. This was due to restrictions on public gatherings imposed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Medals and prizes

The Linnean Society of London aims to promote the study of all aspects of the biological sciences, with particular emphasis on evolution, taxonomy, biodiversity, and sustainability. Through awarding medals and grants, the society acknowledges and encourages excellence in all of these fields.[24][25]

The following medals and prizes are awarded by the Linnean Society:

- Linnean Medal, established 1888, awarded annually to alternately a botanist or a zoologist or (as has been common since 1958) to one of each in the same year.

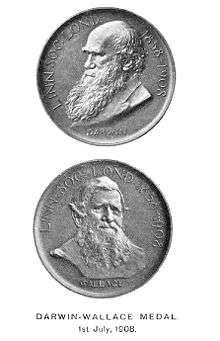

- Darwin-Wallace Medal, first awarded in 1908, for major advances in evolutionary biology.

- H. H. Bloomer Award, established 1963 from a legacy by the amateur naturalist Harry Howard Bloomer, awarded "an amateur naturalist who has made an important contribution to biological knowledge"

- Trail-Crisp Award, established in 1966 from the amalgamation of two previous awards - both dating to 1910 - awarded "in recognition of an outstanding contribution to biological microscopy that has been published in the UK".

- Bicentenary Medal, established 1978, on the 200th anniversary of the death of Linnaeus, "in recognition of work done by a person under the age of 40 years".

- Jill Smythies Award, established 1986, awarded for botanical illustrations.

- Linnean Gold Medal, For services to the society - awarded in exceptional circumstances, from 1988.

- Irene Manton Prize, established 1990, for the best dissertation in botany during an academic year.

- Linnean Tercentenary Medal, awarded in 2007 in celebration of the three hundredth anniversary of the birth of Linnaeus.

- John C Marsden Medal, established 2012, for the best doctoral thesis in biology examined during a single academic year.

- John Spedan Lewis Medal, established 2015, awarded to "an individual who is making a significant and innovative contribution to conservation".

- Sir David Attenborough Award for Fieldwork, established in 2015.

Collections

Linnaeus' botanical and zoological collections were purchased in 1783 by Sir James Edward Smith, the first President of the society, and are now held in London by the society.[26] The collections include 14,000 plants, 158 fish, 1,564 shells, 3,198 insects, 1,600 books and 3,000 letters and documents. They may be viewed by appointment and there is a monthly tour of the collections.[27]

Smith's own plant collection of 27,185 dried specimens, together with his correspondence and book collection, is also held by the society.[28]

Other notable holdings of the society include the notebooks and journals of Alfred Russel Wallace and the paintings of plants and animals made by Francis Buchanan-Hamilton (1762–1829) in Nepal.[29]

In December 2014, the society's specimen, library, and archive collections were granted designated status by the Arts Council England, recognising collections of national and international importance (one of only 148 institutions so recognised as of 2018).[30]

Publications

The Linnean Society began its extensive series of publications on 13 August 1791, when Volume I of Transactions was produced. Over the following centuries the society published a number of different journals, some of which specialised in more specific subject areas, whilst earlier publications were discontinued. Those still in publication include: the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, which covers the evolutionary biology of all organisms, Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, which focuses on plant sciences, and Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society focusing on animal systematics and evolution. The Linnean is a biannual newsletter. It contains commentary on recent activities and events, articles on history and science, and occasional biographies/obituaries of people connected to the Linnean Society; it also includes book reviews, reference material and correspondence. The society also publishes books and Synopses of the British Fauna, a series of field-guides.[31]

Presidents

- 2018– Sandra Knapp

- 2015–2018 Paul Brakefield

- 2012–2015 Dianne Edwards

- 2009–2012 Vaughan R. Southgate

- 2006–2009 David F. Cutler

- 2003–2006 Gordon McGregor Reid

- 2000–2003 Sir David Smith

- 1997–2000 Sir Ghillean Prance

- 1994–1997 Brian G. Gardiner

- 1991–1994 John G. Hawkes

- 1988–1991 Michael Frederick Claridge

- 1985–1988 William Gilbert Chaloner

- 1982–1985 Robert James "Sam" Berry

- 1979–1982 William T. Stearn

- 1976–1979 Humphry Greenwood

- 1973–1976 Irene Manton

- 1970–1973 Alexander James Edward Cave

- 1967–1970 Arthur Roy Clapham

- 1964–1967 Errol White

- 1961–1964 Thomas Maxwell Harris

- 1958–1961 Carl Pantin

- 1955–1958 Hugh Hamshaw Thomas

- 1952–1955 Robert Beresford Seymour Sewell

- 1949–1952 Felix Eugen Fritsch

- 1946–1949 Sir Gavin de Beer

- 1943–1946 Arthur Disbrowe Cotton

- 1940–1943 Edward Stuart Russell

- 1937–1940 John Ramsbottom

- 1934–1937 William Thomas Calman

- 1931–1934 Frederick Ernest Weiss

- 1927–1931 Sidney Frederic Harmer

- 1923–1927 Alfred Barton Rendle

- 1919–1923 Arthur Smith Woodward

- 1916–1919 Sir David Prain

- 1912–1916 Sir Edward Poulton

- 1908–1912 Dukinfield Henry Scott

- 1904–1908 William Abbott Herdman

- 1900–1904 Sydney Howard Vines

- 1896–1900 Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf Günther

- 1894–1896 Charles Baron Clarke

- 1890–1894 Charles Stewart

- 1886–1890 William Carruthers

- 1881–1886 Sir John Lubbock, 4th Baronet (later 1st Baron Avebury)

- 1874–1881 George James Allman

- 1861–1874 George Bentham

- 1853–1861 Thomas Bell

- 1849–1853 Robert Brown

- 1837–1849 Edward Stanley

- 1833–1836 Edward St Maur, 11th Duke of Somerset

- 1828–1833 Edward Smith-Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby

- 1788–1828 Sir James Edward Smith

See also

- Category:Fellows of the Linnean Society of London

- Dorothea Pertz, one of the first women awarded full membership

- Linnaeus Link Project

References

- Annual Review 2019, Linnean Society, p. 18

- Royal patrons and honorary fellows - Linnean Society

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 2, 19

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, p. 148

- O'Brian, P. (1987) Joseph Banks, Collins Harvill. p. 240

- Harris, Henry (1999). The Birth of the Cell. Yale University Press. pp. 76–81.

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, p. 53

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 50, 53, 197-198

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, p. 51

- Cohen, I.B. (1985) Revolution in Science, Harvard University Press, 1985, pp. 288-289

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 88-93

- The Linnean (2005) Vol. 21(2) , p. 25

- Gage, A. T. (1938). A history of the Linnean Society of London: Printed for the Linnean Society by Taylor and Francis, p. 90.

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, p. 95

- Poulton, E. B. 1884. Notes upon, or suggested by, the colours, markings and protective attitudes of certain lepidopterous larvae and pupae, and of a phytophagous hymenopterous larva. Transactions of the Entomological Society of London 1884: 27–60.

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, p. 110

- Preston, Reginald Dawson (1990). "Irene Manton. 17 April 1904-13 May 1988". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 35: 247–261. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1990.0011.

- Biography of Irene Manton sponsored by the Linnean Society, in The Linnean, Special Issue No. 5 (2004)

- John Spedan Lewis Medal

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 195, 198-202

- The Charter and Bye-laws of the Linnean Society

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 149-152

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 149-152

- The Linnean Society of London: Medals and Prizes

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 165-174

- "The purchase of knowledge: James Edward Smith and the Linnean collections" (PDF). www.warwick.ac.uk. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-13. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- The Linnean Society of London: Linnean Collections

- The Linnean Society of London: Smith Collections

- Gage A. T. and Stearn W. T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 175-181 (specimen collections) 183-188 (manuscript, illustration and publication collections)

- Linnean Society is one of four collections nationally recognised

- Gage A.T. and Stearn W.T. (1988) A Bicentenary History of the Linnean Society of London, Linnean Society of London, pp. 153-164

External links

![]()

![]()

- Linnean Society of London

- Home page of the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society

- Home page of the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society

- Home page of the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society

- BHL scans of Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 1791-1874

- BHL scans of Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 2nd series, Zoology 1875-1921

- BHL scans of Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, 2nd series: Botany 1875-1922

- Works by Linnean Society of London at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Linnean Society of London at Internet Archive