Burlington House

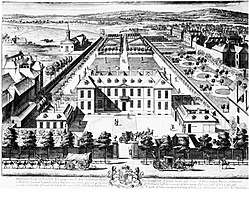

Burlington House is a building on Piccadilly in Mayfair, London. It was originally a private Palladian mansion owned by the Earls of Burlington and was expanded in the mid-19th century after being purchased by the British government.

.jpg)

Burlington House is most familiar to the general public as the venue for temporary art exhibitions from the Royal Academy, which are housed in the main building at the northern end of the courtyard. Five learned societies occupy the two wings on the east and west sides of the courtyard and the Piccadilly wing at the southern end. Collectively known as the Courtyard Societies, these societies are as listed below:

- Geological Society of London (Piccadilly/east wing)

- Linnean Society of London (Piccadilly/west wing)

- Royal Astronomical Society (west wing)

- Society of Antiquaries of London (west wing)

- Royal Society of Chemistry (east wing)

Burlington House has been listed Grade II* on the National Heritage List for England since February 1970.[1]

History

The house was one of the earliest of a number of very large private residences built on the north side of Piccadilly, previously a country lane, from the 1660s onwards. The first version was begun by Sir John Denham in about 1664.[2] It was a red-brick double-pile hip-roofed mansion with a recessed centre, typical of the style of the time, or perhaps even a little old fashioned. Denham may have acted as his own architect, or he may have employed Hugh May, who certainly became involved in the construction after the house was sold in an incomplete state in 1667 to Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Burlington, from whom it derives its name.[3] Burlington had the house completed, which was the largest structure on his land, the Burlington Estate.

In 1704, the house was passed on to ten-year-old Richard Boyle, third Earl of Burlington, who was to become the principal patron of the Palladian movement in England, and an architect in his own right. Around 1709, during Burlington's minority, Lady Juliana Boyle, the second Countess, commissioned James Gibbs to reconfigure the staircase and make exterior alterations to the house, including a quadrant Doric colonnade which was later praised by Sir William Chambers as "one of the finest pieces of architecture". The colonnade separated the house from increasingly urbanized Piccadilly with a cour d'honneur. Inside, Baroque decorative paintings in the entrance hall and a staircase by Sebastiano Ricci and Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini makes it one of the richest interiors in London.[4]

In between his two Grand Tours of Italy (1714 and 1719), young Lord Burlington's taste (the third Earl) was transformed by the publication of Giacomo Leoni's Palladio which made him develop a passion for Palladian architecture. In 1717 or 1718, the third Earl began making major modifications to Burlington House and the supervision of the work was undertaken by Gibbs. Later, Colen Campbell was appointed to replace Gibbs, who was working in the Baroque style of Sir Christopher Wren, to recast the work in a new manner on the old foundation. This was a key moment in the history of English architecture, as Campbell's work was in a strict Palladian style, and the aesthetic preferences of Campbell and Burlington, soon joined by the aesthetic style of their close associate William Kent, who worked on interiors at Burlington House, were to provide the leading strain in English architecture and interior decoration for two generations. Campbell's work closely followed the form of the previous building and reused much of the structure, but the conventional front (south) façade was replaced with an austere two-storey composition, taking Palladio's Palazzo Iseppo di Porti, Vicenza, for a model[5] but omitting sculpture and substituting a balustrade for the attic storey. The ground floor became a rusticated basement, which supported a monumental piano nobile of nine bays. This had no centrepiece but was highlighted by venetian windows in the projecting end bays, the first to be seen in England. Other alterations included a monumental screening gateway to Piccadilly and the reconstruction of most of the principal interiors, with typical Palladian features such as rich coved ceilings. The Saloon, constructed immediately after William Kent's return from Rome in December 1719, has survived in the most intact condition; it was the first Kentian interior designed in England. Its plaster putti above the pedimented doorcases were probably by Giovanni Battista Guelfi.[6]

Lord Burlington transferred his architectural energies to Chiswick House after 1722. After Burlington's death in 1753, Burlington House was passed on to the Dukes of Devonshire, but they had no need of it as they already owned Devonshire House just along Piccadilly. The fourth Duke's younger son Lord George Cavendish and a Devonshire in-law, the third Duke of Portland, each used the house for at least two separate spells. Portland had some of the interiors altered by John Carr in the 1770s. Eventually Lord George, who was a rich man in his own right due to his having married an heiress, purchased the house from his nephew, the sixth Duke of Devonshire, for £70,000 in 1815. Lord George employed Samuel Ware to shift the staircase to the centre and reshape the interiors to provide a suite of "Fine Rooms" en filade linking the new state dining room at the west end[7] to the new ballroom at the east end. Like Carr's work, Ware's was sympathetic with the Palladian style of the house, providing an early example of the "Kent Revival",[6] a particularly English prefiguration of Baroque Revival architecture. In 1819 the Burlington Arcade was built along the western part of the grounds.

In 1854, Burlington House was sold to the British government for £140,000, originally with the plan of demolishing the building and using the site to build the University of London. This plan, however, was abandoned in the face of strong opposition, and in 1857 Burlington House was occupied by the Royal Society, the Linnean Society and the Chemical Society (later the Royal Society of Chemistry).

The Royal Academy took over the main block in 1867 on a 999-year lease with rent of £1 per year; it was required to pay for its top-lit main galleries, designed by Sidney Smirke on a part of the gardens to the north of the main range and its art school premises; Smirke also raised the central block with a third storey. The former east and west service wings on either side of the courtyard and the wall and gate to Piccadilly were replaced by much more voluminous wings by the partnership of Robert Richardson Banks and Charles Barry, Jr.,[8] in an approximation of Campbell's style. These were completed in 1873, and the three societies moved into these. In 1874 they were joined by the Geological Society of London, the Royal Astronomical Society and the Society of Antiquaries.

This arrangement lasted until 1968, when the Royal Society moved to new premises in Carlton House Terrace and its apartments were split between the Royal Society of Chemistry and the British Academy. The British Academy also moved to Carlton House Terrace in 1998 and the Royal Society of Chemistry took over the rest of the east wing.

In 2004 the Courtyard Societies went to court against the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister over the terms of their tenure of the apartments in Burlington House, which they have enjoyed rent-free.[9] The dispute was sent to mediation, after which the following statement was released: "The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister and the Learned Societies had a very constructive meeting on 16 March which envisages the continued presence of the Learned Societies at Burlington House. Discussions are continuing with a view to formalising the arrangement on a basis which is acceptable to all parties."

Public access

The courtyard of Burlington House, known as the "Annenberg Courtyard",[10] is open to the public during the day. It features a statue of Joshua Reynolds and fountains arranged in the pattern of the planets at the time of his birth.[10]

The Royal Academy's public art exhibitions are staged in nineteenth-century additions to the main block which are of little architectural interest. However, in 2004 the principal reception rooms on the piano nobile were opened to the public after restoration as the "John Madejski Fine Rooms". They contain many of the principal works in the academy's permanent collection, which predominantly features works by Royal Academicians and small temporary exhibitions drawn from the collection. The east, west and Piccadilly wings are occupied by the learned societies and are generally not open to the public.

See also

References

- Historic England, "Royal Academy including Burlington House and galleries and Royal Academy School buildings (1226676)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 14 December 2017

- Date in The John Madeski Fine Rooms: An Architectural Guide (Royal Academy of Arts).

- "Burlington House | Survey of London: volumes 31 and 32 (pp. 390–429)". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Pellegrini's decorations were removed by 1727 and survive at Narford Hall, Norfolk; canvases from Ricci's screen are no longer in situ but remain at Burlington House (The John Madeski Fine Rooms).

- "A fairly faithful transcript", according to James Lees-Milne, The Earls of Creation, 1962:99; Leoni had provided an engraving; Campbell had already used the scheme in a design dedicated to Lord Islay in his Vitruvius Britannicus.

- The John Madeski Fine Rooms.

- Now the General Assembly Room, it was originally a bedroom; its opening into the enfilade was blocked in 1885 by Richard Norman Shaw, who centred the room on his new staircase; the enfilade has been reopened with the restoration of the "Fine Rooms".

- Charles Barry, Jr. was the son of the better-known Sir Charles Barry, architect of the Houses of Parliament.

- Adam, David (31 January 2004). "Royal societies facing eviction in row over rent". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- "About Us". Burlington House. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- David Pearce, London's Mansions (1986). ISBN 0-7134-8702-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burlington House. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Burlington House. |

- Burlington House – arts and sciences in the heart of London – The Burlington House lectures represent a joint interdisciplinary initiative organised in conjunction with the Royal Academy and the five learned societies that occupy this historic building.

- Survey of London – very detailed coverage of Burlington House from the government sponsored survey of London (1963).

- Article 'The Burlington Five' published in The Times, 18 January 2004