Catawba people

The Catawba, also known as Issa, Essa or Iswä but most commonly Iswa (Catawba: Iswa – "people of the river"), are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans, known as the Catawba Indian Nation.[2] They live in the Southeastern United States, on the Catawba River at the border of North Carolina, near the city of Rock Hill, South Carolina. They were once considered one of the most powerful Southeastern Siouan-speaking tribes in the Carolina Piedmont, as well as one of the most powerful tribes in the South as a whole.

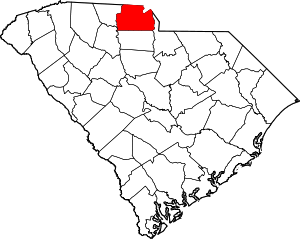

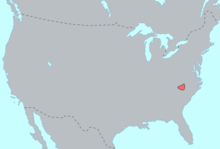

Pre-contact distribution of the Catawba | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2010: 3,370[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, revival of Catawba | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional Indigenous (private), Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms), Mormon | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lumbee, Waccamaw, Eno, Shakori, and other Siouan peoples |

The Catawba were among the East Coast tribes who made selective alliances with some of the early European colonists, when these colonists agreed to help them in their ongoing conflicts with other tribes in the region. These were primarily the tribes of different language families: the Iroquois, who ranged south from the Great Lakes area and New York; the Algonquian Shawnee and Lenape (Delaware); and the Iroquoian Cherokee, who fought for control over the large Ohio Valley (including what is in present-day West Virginia).[3] During the American Revolutionary War the Catawba supported the American colonists against the British. Decimated by colonial smallpox epidemics, warfare and cultural disruption, the Catawba declined markedly in number in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Some Catawba continued to live in their homelands in South Carolina, while others joined the Choctaw or Cherokee, at least temporarily.

Terminated as a tribe by the federal government in 1959, the Catawba Indian Nation had to reorganize to reassert their sovereignty and treaty rights. In 1973 they established their tribal enrollment and began the process of regaining federal recognition. In 1993 their federal recognition was re-established, along with a $50 million settlement by the federal government and state of South Carolina tor their longstanding land claims. The tribe was also officially recognized by the state of South Carolina in 1993. Their headquarters are at Rock Hill, South Carolina.

As of 2006, the population of the Catawba Nation has increased to about 2600, most in South Carolina, with smaller groups in Oklahoma, Colorado, Ohio, and elsewhere. The Catawban language, which is being revived, is part of the Siouan family (Catawban branch).[4]

History

From the earliest period, the Catawba have also been known as Esaw, or Issa (Catawba iswä, "river"), from their residence on the principal stream of the region. They called both the present-day Catawba and Wateree rivers Iswa. The Iroquois frequently included them under the general term Totiri, or Toderichroone, also known as Tutelo. The Iroquois collectively used this term to apply to all the southern Siouan-speaking tribes.

Albert Gallatin (1836) classified the Catawba as a separate, distinct group among Siouan tribes. When the linguist Albert Samuel Gatschet visited them in 1881 and obtained a large vocabulary showing numerous correspondences with Siouan, linguists classified them with the Siouan-speaking peoples. Further investigations by Horatio Hale, Gatschet, James Mooney, and James Owen Dorsey proved that several tribes of the same region were also of Siouan stock.

In the late nineteenth century, the ethnographer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft wrote that the Catawba had lived in Canada until driven out by the Iroquois (supposedly with French help), and that they had migrated to Kentucky and to Botetourt County, Virginia. He asserted that by 1660 they had migrated south to the Catawba River, contesting it with the Cherokee in the area. But, 20th-century anthropologist James Mooney later dismissed most elements of Schoolcraft's record as "absurd, the invention and surmise of the would-be historian who records the tradition." He pointed out that, aside from the French never having been known to help the Iroquois, the Catawba had been recorded by 1567 in the same area of the Catawba River as their later territory. Mooney accepted the tradition that the Catawba and Cherokee had made the Broad River their mutual boundary, following a protracted struggle.[5]

The Catawba were long in a state of conflict with several northern tribes, particularly the Iroquois Seneca, and the Algonquian-speaking Lenape. The Catawba chased Lenape raiding parties back to the north in the 1720s and 1730s, going across the Potomac River. At one point, a party of Catawba is said to have followed a party of Lenape who attacked them, and to have overtaken them near Leesburg, Virginia. There they fought a pitched battle.[6]

Similar encounters in these longstanding conflicts were reported to have occurred at present-day Franklin, West Virginia (1725),[7] Hanging Rocks and the mouth of the Potomac South Branch in West Virginia, and near the mouths of Antietam Creek (1736) and Conococheague Creek in Maryland.[8] Mooney asserted that the name of Catawba Creek in Botetourt came from an encounter in these battles with the northern tribes, not from the Catawba having lived there.

The colonial governments of Virginia and New York held a council at Albany, New York in 1721, attended by delegates from the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee) and the Catawba. The colonists asked for peace between the Confederacy and the Catawba, however the Six Nations reserved the land west of the Blue Ridge mountains for themselves, including the Indian Road or Great Warriors' Path (later called the Great Wagon Road) through the Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia backcountry. This heavily traveled path, used until 1744 by Seneca war parties, went through the Shenandoah Valley to the South.

In 1738, a smallpox epidemic broke out in South Carolina. It caused many deaths, not only among the Anglo-Americans, but especially among the Catawba and other tribes, such as the Sissipahaw. They had no natural immunity to the disease, which had been endemic in Europe for centuries. In 1759, a smallpox epidemic killed nearly half the tribe. Native Americans suffered high fatalities from such infectious Eurasian diseases.

In 1744 the Treaty of Lancaster, made at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, renewed the Covenant Chain between the Iroquois and the colonists. The governments had not been able to prevent settlers going into Iroquois territory, but the governor of Virginia offered the tribe payment for their land claim. The peace was probably final for the Iroquois, who had established the Ohio Valley as their preferred hunting ground by right of conquest. The more western tribes continued warfare against the Catawba, who were so reduced that they could raise little resistance. In 1762, a small party of Algonquian Shawnee killed the noted Catawba chief, King Hagler, near his own village.

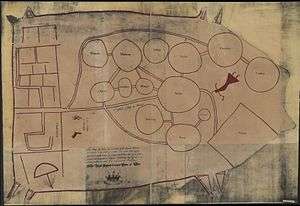

In 1763, South Carolina confirmed a reservation for the Catawba of 225 square miles (580 km2; 144,000 acres), on both sides of the Catawba River, within the present York and Lancaster counties. When British troops approached during the American Revolutionary War in 1780, the Catawba withdrew temporarily into Virginia. They returned after the Battle of Guilford Court House, and settled in two villages on the reservation. These were known as Newton, the principal village, and Turkey Head, on opposite sides of Catawba River.

19th-century

In 1826, the Catawba leased nearly half their reservation to whites for a few thousand dollars of annuity, on which the few survivors (as few as 110 by one estimate[9]) chiefly depended. In 1840 by the Treaty of Nation Ford with South Carolina, the Catawba sold all but one square mile (2.6 km2) of their 144,000 acres (225 sq mi; 580 km2) reserved by the King of England to the state. They resided on the remaining square mile after the treaty. The treaty was invalid ab initio because the state did not have the right to make it and did not get federal approval.[10] About the same time, a number of the Catawba, dissatisfied with their condition among the whites, removed to join the eastern Cherokee in western North Carolina. But, finding their position among their old enemies equally unpleasant, all but one or two soon returned to South Carolina. An old woman, the last survivor of this emigration, died among the Cherokee in 1889. A few Cherokee intermarried with the Catawba.

At a later period some Catawba removed to the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory and settled near present-day Scullyville, Oklahoma. They merged with the Choctaw and did not retain separate tribal identity.

Historical culture

The Catawba were sedentary agriculturists, who also fished and hunted for game. They had customs similar to neighboring Native Americans in the Piedmont. The men were good hunters. The women have been noted makers of pottery and baskets, arts which they still preserve.[3] They seem to have practiced the custom of head-flattening to a limited extent, as did several of the neighboring tribes. By reason of their dominant position, the Catawba had gradually absorbed the broken tribes of South Carolina, to the number, according to Adair, of perhaps 20.

Early Spanish explorers estimated their population between 15,000 and 25,000 people. When the English first settled South Carolina about 1682, they estimated the Catawba at about 1,500 warriors, or about 4,600 people in total because of the diseases that the English carried. They named the Catawba River and Catawba County after the indigenous people. By 1728, the Catawba had been reduced to about 400 warriors, or about 1400 persons in total. In 1738, they suffered from a smallpox epidemic, which also affected nearby tribes and the whites. In 1743, even after incorporating several small tribes, the Catawba numbered fewer than 400 warriors. In 1759, they again suffered from smallpox, and in 1761, had some 300 warriors, or about 1,000 people. By 1775 they had only 400 people in total; in 1780, they had 490; and, in 1784, only 250 were reported.

During the nineteenth century, their numbers continued to decline, to 450 in 1822, and a total of 110 people in 1826. As of 2006, their population had increased to about 2600.

Religion and culture

The customs and beliefs of the early Catawba were documented by the anthropologist Frank Speck in the twentieth century.

In the Carolinas, the Catawba became well known for their pottery, which has historically been made primarily by the women, but is now also made by some of the men, as well.[11]

In approximately 1883, tribal members were contacted by missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Numerous Catawba were converted to the church, and some migrated to Colorado and Utah and neighboring western states.[12]

The Catawba hold a yearly celebration called Yap Ye Iswa, which roughly translates to Day of the People, or Day of the River People. Held at the Catawba Cultural Center, proceeds are used to fund the activities of the center.

20th century to present

The Catawba were electing their chief prior to the start of the 20th century. In 1909 the Catawba sent a petition to the United States government seeking to be given United States citizenship.[13]

During the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, the federal government worked to improve conditions for Native Americans. Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, tribes were encouraged to renew their governments for more self-determination. The Catawba were not at that time a recognized Native American tribe. In 1929 the Chief of the Catawba, Samuel Taylor Blue, had begun the process to gain federal recognition. The Catawba were recognized as a Native American tribe in 1941 and they created a written constitution in 1944. Also in 1944 South Carolina granted the Catawba and other Native American residents of the state citizenship, but not to the extent of granting them the right to vote. Like African Americans, they were largely excluded from the franchise. That right would be denied to the Catawba until the 1960s, when they gained it as a result of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which provided for federal enforcement of people's constitutional right to vote.

As a result of the federal government's Indian termination policy in the 1950s of its special relationship with some Indian tribes that it determined were ready for assimilation, it terminated the government of the Catawba in 1959. This meant also that the members of the tribe ceased to have federal benefits, their assets were divided, and the people were subject to state law. The Catawba found that they preferred to be organized as a tribal community. Beginning in 1973, they applied to have their government federally recognized, with Gilbert Blue serving as their chief until 2007. They adopted a constitution in 1975 that was modeled on their 1944 version.

In addition, for decades the Catawba pursued various land claims against the government for the losses due to the illegal treaty made by South Carolina in 1840 and the failure of the federal government to protect their interests. On October 27, 1993, the U.S. Congress enacted the Catawba Indian Tribe of South Carolina Land Claims Settlement Act of 1993 (Settlement Act), which reversed the "termination", recognized the Catawba Indian Nation and, together with the state of South Carolina, settled the land claims for $50 million to go toward economic development for the Nation.[14]

On July 21, 2007, the Catawba held their first elections in more than 30 years. Of the five members of the former government, only two were reelected.[15]

In the 2010 census, 3,370 people claimed Catawba ancestry.

Catawba Indian Nation Land Trust

The Catawba Reservation (34°54′17″N 80°53′01″W), located in two disjoint sections in York County, South Carolina east of Rock Hill; a total of 1,012 acres (410 ha), it reported a 2010 census population of 841 inhabitants. It also has a congressionally established service area in North Carolina, covering Mecklenburg, Cabarrus, Gaston, Union, Cleveland and Rutherford counties. The Catawba also owns a 16.57-acre (6.71 ha) site in Kings Mountain, North Carolina, which will be used for a casino and mixed-use entertainment complex.[16]

Today the Catawba earns most of its revenue from Federal/State funds.

Gaming relations with South Carolina

Under the terms of the 1993 Settlement Act, the Catawba waived its right to be governed by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. Instead, the Catawba agreed to be governed by the terms of the Settlement Agreement and the State Act as pertains to games of chance; which at the time allowed for video poker and bingo. In 1996, the Catawba formed a joint venture partnership with D.T. Collier of SPM Resorts, Inc. of Myrtle Beach, to manage their bingo and casino operations. That partnership, New River Management and Development Company, LLC (of which the Catawba were the majority owner) operated the Catawba's bingo parlor in Rock Hill. In 1999, the South Carolina General Assembly passed a statewide ban on the possession and operation of video poker devices.

When in 2004 the Catawba entered into an exclusive management contract with SPM Resorts, Inc., to manage all new bingo facilities, some tribal members were critical. The new contract was signed by the former governing body immediately prior to new elections. In addition, the contract was never brought before the General Council (the full tribal membership) as required by their existing constitution.[17] After the state established the South Carolina Education Lottery in 2002, the tribe lost gambling revenue and decided to shut down the Rock Hill bingo operation. They sold the facility in 2007.[18]

In 2006, the bingo parlor, located at the former Rock Hill Mall on Cherry Road, was closed. The Catawba filed suit against the state of South Carolina for the right to operate video poker and similar "electronic play" devices on their reservation. They prevailed in the lower courts, but the state appealed the ruling to the South Carolina Supreme Court. The state Supreme Court overturned the lower court ruling. The tribe appealed that ruling to the United States Supreme Court, but in 2007 the court declined to hear the appeal.[19] In 2014, similar decision was handed by the Supreme Court of South Carolina in regards of the state's Gambling Cruise Act.[20]

In 2014, the Catawba made a second attempt with bingo, opening a parlor, site formally a BI-LO, on Cherry Road in Rock Hill. It closed in 2017, unable to turn a profit.[21]

Gaming relations with North Carolina

On September 9, 2013, the Catawba announced plans to build a $600 million casino along Interstate 85 in Kings Mountain, North Carolina.[22] Cleveland County officials quickly endorsed the plans; while Governor Pat McCrory, over 100 North Carolina General Assembly members and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) opposed it.[23]

Submitting a mandatory acquisition application to the United States Department of the Interior (DOI) in August 2013 to place the 16.57-acre (6.71 ha) site in trust, the application was denied in March 2018. In September, the Catawba submitted a new application under the discretionary process; they also pursued a legislative route, senate bill 790, introduced by South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, with support of North Carolina Senators Thom Tillis and Richard Burr, would have authorized the DOI to take the land into trust for gaming, but the bill died in committee.[24]

On March 13, 2020, the DOI announced its decision to approve the 2018 discretionary application and place the land in North Carolina in trust.[16] On March 17, the EBCI filed a suit in the U.S. District Court in the District of Columbia against the Federal Government. The suit names the DOI, the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Secretary David Bernhardt, and several other department officials. In addition, the Catawba filed a motion to intervene to join the defendants, while the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma also filed a motion to support the EBCI; both motions were approved. In May, the EBCI filed an amended complaint in its federal lawsuit, indicating the DOI's acquisition of land was a result a scheme by casino developer Wallace Cheves, who prevailed upon the Catawba Indian Nation of South Carolina to lend its name to a scheme and who has a history of criminal and civil enforcement actions against him and his companies for illegal gambling. It also included the DOI disregard of early consultation with the EBCI and it was rushed skipping a Environmental Impact Assessment. The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma also filed its own amended complaint, seeking to protect cultural artifacts on their ancestral land where the illegal casino is planned.[24][25][26][27]

Footnotes

- "2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native The United States and Puerto Rico: 2010" (PDF). census.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-09.

- Catawba Indian Nation

- Sultzman, Lee. Catawba History. Clay Hound: Native American Traditional Pottery. (retrieved 14 March 2009)

- William C. Sturtevant, "Siouan Languages in the East", American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 60, No. 4 (Aug 1958), pp. 738–743 (retrieved through Jstor.org, 14 March 2009)

- Mooney, Siouan Tribes of the East p. 69.

- Legends of Loudoun, Harrison Williams, p. 63–64

- Frederic Morton, The Story of Winchester in Virginia p. 38

- Joseph Doddridge, 1850, A History of the Valley of Virginia, pp. 29–33.

- Scaife, Hazel Lewis (1896). History and Condition of the Catawba Indians of South Carolina. Philadelphia: Office of Indian Rights Association. p. 10. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Steven Paul McSloy, "Revisiting the "Courts of the Conqueror:" American Indian Claims Against the United States", American University Law Review, Vol. 44:537, 1994, p. 549

- Catawba Indian Pottery The Survival of a Folk Tradition. Thomas John Blumer ISBN 0-8173-1383-4 Contemporary American Indian Studies. J. Anthony Paredes, Series Editor.

- Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, p. 1165

- Blummer, The Catawba Nation (Historians Press, 2007), p. 101

- McSloy, "Revisiting the "Courts of the Conqueror:" American Indian Claims Against the United States", 1994, p. 552

- "New Catawba leader faces uphill climb", Indian Country, 13 Aug 2007

- "Catawba Indian Nation - Indian Affairs" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. March 12, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Tribal members protest Catawba Bingo" Archived 2007-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Indian Country, 6 Apr 2004

- "The lottery at 5 years: Tribe says lottery killed its business" Archived 2007-12-19 at the Wayback Machine, The State, 18 Dec 2007

- U.S Supreme Court Order List — October 1, 2007

- "Catawba Indian Nation v. State of South Carolina and Mark Keel, in his official capacity as Chief of the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division, Respondents". April 2, 2014. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Harris, Amanda (May 11, 2017). "Catawba Indian Nation closes bingo hall in Rock Hill". The Herald. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Elkins, Ken (September 9, 2013). "Catawbas push to open $600M casino in Kings Mountain". Charlotte Business Journal. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Elkins, Ken (September 17, 2013). "N.C. Gov. McCrory won't support Catawba casino in Kings Mountain". Charlotte Business Journal. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Dillon, A.P. (March 18, 2020). "Proposed Catawba Indian casino in King's Mountain moves forward". North State Journal. Raleigh, NC. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Orlando, Joyce (May 27, 2020). "Tribes continue battle for proposed casino in Kings Mountain". The Shelby Star. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians files amended complaint against U.S. Department of the Interior". Mountain Xpress. Asheville, NC. July 8, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Morrill, Jim (July 17, 2020). "Vegas coming to Charlotte area: Catawbas plan casino groundbreaking for Wednesday". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

Further reading

- Beck, Robin. Chiefdoms, Collapse, and Coalescence in the Early American South. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Brown, Douglas S.The Catawba Indians: People of the River, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1966; reprinted 1983.

- Christie, John C., Jr. "The Catawba Indian Land Claim: A Giant among Indian Land Claims," American Indian Culture and Research Journal, vol. 24, no. 1 (2000), pp. 173–182.

- Drye, Willie. "Excavated Village Unlocks Mystery of Tribe's Economy", National Geographic News, Nov. 14, 2005.

- Hudson, Charles M. The Catawba Nation, University of Georgia Monograph No. 18 (1970).

- Merrell, J. H. The Indians' New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact Through the Era of Removal, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

- Speck, Frank G. (1913). "Some Catawba Texts and Folk-lore," Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 26, pp. 81–84. and pp. 319–330.

- Speck, Frank G. (1939). Catawba Religious Beliefs, Mortuary Customs, and Dances by Frank G. Speck, Primitive Man, 12, 2, April, pp. 21–57. Published by: The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research.

- Speck, Frank G. (1934). Catawba Texts, New York: Columbia University Press, 91 pp.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Catawba. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Catawbas. |

- Catawba Indian Nation

- The Catawba Cultural Preservation Project

- Information on Catawba

- Looking Back – The Catawba

- The Catawba Indians: "People of the River", Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History