Augustan and Julio-Claudian art

Augustan and Julio-Claudian art is the artistic production that took place in the Roman Empire under the reign of Augustus and the Julio-Claudian dynasty, lasting from 44 BC to 69 AD. At that time Roman art developed towards a serene "neoclassicism", which reflected the political aims of Augustus and the Pax Romana, aimed at building a solid and idealized image of the empire.

.jpg)

The art of the age of Augustus is characterized by refinement and elegance, adapted to the sobriety and measure that Augustus had imposed on himself and his court. During the principality of Augustus, a radical urban transformation of Rome began in a monumental sense. Suetonius recalls that:

Rome was not up to the grandeur of the Empire and was exposed to floods and fires, but he embellished it to such an extent that he rightly boasted of leaving the city he had found made of bricks of marble. In addition to that, it also made her safe for the future, as far as she could provide for posterity."[1]

Still influential was the Greek sculpture from the 5th century BC, of which many works remained. This continuation of neo-Atticism influenced architecture, craftsmanship, and painting. Emblematic works of this era are the Ara Pacis, the Via Labicana Augustus, and the Augustus of Prima Porta.

Evolution in the politics and iconography of Augustus

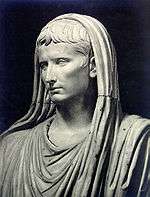

Portrait of Octavian at the Capitoline Museums |

The political evolution of Augustus was promptly reflected in official art, as evidenced by the series of imperial portraits. Typical features of his portraits are the steady eyes, the straight nose, the rather hollowed face, the well-pronounced cheekbones, the thin mouth, and a lock of hair "with a pincer" on the right side of the forehead.

The portrait of Octavian at the Capitoline Museums dates back to the period between 35 and 30 BC, when Augustus had not yet assumed the imperial titles and was still taken by the struggle for political supremacy. He has a vehement expression, but with the aura of inspiration typical of portraits of Hellenistic rulers.

Conversely, the statues of the Augustus of Prima Porta and of the Augustus Via Labicana have a composure reminiscent of Polykleitos and the other classical Greek sculptors. These show an expression of proud reserve, a disposition Augustus demonstrated in his Res Gestae Divi Augusti.

The official iconography of Augustus was widespread. The Res Gestae reports that about 80 statues made of silver were erected in the Empire.[2]

The portraits of the members of Augustus' family were based on the resemblance to Augustus, almost canceling the individual features to accentuate the common features as much as possible.

Sculpture

At the time of Augustus, works of careful technical and formal perfection were produced. Artists were devoted to combining detailed realism with creativity richness. This era was defined by neo-Atticim, and was ultimately a brake on the nascent individuality of Roman art.

The Ara Pacis is a symbol of the Augustan era, constructed between 13 BC and 9 BC. The general Italic approach is mixed with neo-Attic reliefs and a frieze in the style of Pergamon; all combined without precise logical relationships between architectural parts and decorations. Only the small frieze on the central altar is considered a truly local artwork.

The Ara Pietatis, constructed under the reign of Claudius, is considered a more unified work. Artworks constructed under Claudius lacked warmth and color found in other eras.

Architecture

During the time of Augustus, Rome took on the appearance similar to that of the most important Hellenistic cities. Augustus oversaw the replacement of many terracotta constructions with marble.

In this period, there was more experimentation with architecture, notably concerning triumphal arches, baths, amphitheaters, and mausoleums in Rome. The Arch of Augustus, for example, was the first permanent three-bayed arch ever built in Rome. It was erected by Augustus around 20 BC.

In this period there were more buildings dedicated to entertainment: the Roman Theatre of Orange was founded in 40 BC, the Theatre of Marcellus dates back to 11 BC, and the Pula Arena was built in a time between Claudius and Titus.

The influence of Roman architecture on Greece can also be seen in this era. This is evident with the Roman Agora, constructed in 15 BC.

Painting

In this period we see the transition from the second to the third Pompeian Style.

Painted within the House of Livia on the Palatine Hill in Rome, there is a classic example of a second style. The decoration of the Casa della Farnesina, attributed to the painter Studius between 30 BC and 20 BC, was mentioned by Pliny the Elder.[3] It is attributable to the third style.

At the end of the reign of Augustus, there were detailed garden frescoes painted in the large room of the Villa of Livia. The same painters also likely decorated the Auditorium of Mecenate (now largely lost without adequate photographic cataloging after the discovery). The painting of these types of gardens derives from eastern influence, with lower quality examples found in some tombs of the Gabbari necropolis.

The most famous hall of the Villa of the Mysteries also likely dates back to the time of Augustus, where copies of Greek paintings and Roman insertions are mixed.

The reconstructions of Pompeii after the earthquake of 62 saw new decorations, for the first time in the so-called fourth style. Also done in this style is the decorations of the Domus Transitoria and the Domus Aurea, linked to the names of the painter Fabullus and Nero himself.

Toreutics and glyptics

Roman toreutics was initiated by Greek artists such as Pasiteles, who also wrote several books on chasing. In the period of Augustus, this art had a remarkable technical and artistic level, demonstrated by the numerous silver pieces found in various parts of the Empire, notably the Hildesheim Treasure.

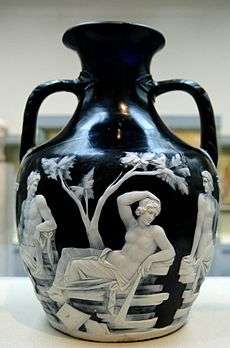

Many high quality artifacts of this type remain, including large cameos. After 29 BC, the Gemma Augustea was created. The Great Cameo of France followed in the era of Tiberius.

The Gemma Augustea

The Gemma Augustea The Gemma Claudia

The Gemma Claudia Cameo with the profile of Augustus

Cameo with the profile of Augustus The Portland Vase

The Portland Vase

Provincial art

The great development from which the western provinces benefited in this period coincided with the birth and establishment of the characteristics of provincial art. The art of the Roman provinces was based on the artistic tradition of plebeian art, which was already widespread among the Roman middle class, usually called to form the nuclei of the new colonies of veterans. Among the most evident examples is that of production in the colony of Aquileia.

Works that were widespread in the provinces were funeral monuments decorated with reliefs, where the client's social status, businesses and public services were highlighted (as in the Funerary Monument of Lusius Storax). The portraits in these works are almost always generic, without real individualized details. As a result, it is often useless to try to date them based on the hairstyles and styles of the clothes depicted in the art.

There are two main original trends observed in provincial art: The conception of figures carved in blocks, with accentuation of mass at the edges ("cubistic" conception, which had also existed in Etruscan art and then disappeared in the Republican era); and figures with expressions of a gentler nature.

Gaul Narbonensis

Unique are the characteristics of the artistic production in Gallia Narbonensis (Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Carpentras, Orange). The monuments of this province, whose dating has long been discussed, present a rich style, with greater spatial freedom even than the coeval monuments of Rome, with stylistic elements (such as the outline of the figures highlighted with a carved line) which appear in Rome only from the second century. Notable constructions include the Mausoleum of the Julii, dated between 25 BC and 30 BC, and the Triumphal Arch of Orange from 26 AD.

.jpg) Relief on the Triumphal Arch of Orange

Relief on the Triumphal Arch of Orange

Notable artists

The list of notable Roman artists from the period includes:

- Cocceius Auctus, arcitect

- Ennion, glassworker

- Famulus, painter

- Lucius Vitruvius Cerdo, architect

- Quintus Pedius, painter

- Proclus, mosaicist

- Spurius Tadius, painter

- Vitruvius, architect

Notes

- Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. "Vita divi Augusti". De vita Caesarum libri VIII. p. 28.

- Augustus. "II". Res Gestae Divi Augusti. p. 24. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Pliny, Natural history, XXXV, 16.

Bibliography

- (in Italian) Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli & Mario Torelli, L'arte dell'antichità classica, Etruria-Roma, Utet, Torino 1976.

- (in Italian) Pierluigi De Vecchi & Elda Cerchiari, I tempi dell'arte, volume 1, Bompiani, Milano 1999

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Augustan and Julio-Claudian art. |