Erlking

"Erlking" (German: Erlkönig, lit. 'alder-king') is a name used in German Romanticism for the figure of a spirit or "king of the fairies". It is usually assumed that the name is a derivation from the ellekonge (older elverkonge, i.e. "Elf-king") in Danish folklore.[1] The name is first used by Johann Gottfried Herder in his ballad "Erlkönigs Tochter" (1778), an adaptation of the Danish Hr. Oluf han rider (1739), and was taken up by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his poem "Erlkönig" (1782), which was set in music by Schubert, among others.[2] In English translations of Goethe's poem, the name is sometimes rendered as Erl-king.

Origin

According to Jacob Grimm, the term originates with a Scandinavian (Danish) word, ellekonge "king of the elves",[3] or for a female spirit elverkongens datter "the elven king's daughter", who is responsible for ensnaring human beings to satisfy her desire, jealousy or lust for revenge.[4][5] The New Oxford American Dictionary follows this explanation, describing the Erlking as "a bearded giant or goblin who lures little children to the land of death", mistranslated by Herder as Erlkönig in the late 18th century from ellerkonge.[6] The correct German word would have been Elbkönig or Elbenkönig, afterwards used under the modified form of Elfenkönig by Christoph Martin Wieland in his 1780 poem Oberon.[7]

It has been suggested, that the term may derive not from "elf-king" but from the name of Herla, a figure in medieval English folklore, adapted as Herlequin, Hellequin in medieval French, in origin the leader of the Wild Hunt, in French known as maisnie Hellequin "household of Hellequin" (and as such ultimately identical with Woden), but recast as a generic "devil" in the course of the Middle Ages (and incidentally, in the 16th century also the origin of the Harlequin character). Sometimes also associated is the character of Herrequin, a ninth-century count of Boulogne of proverbial wickedness.[8]

Herla is cast in the role of a king of the Britons who ends up spending three centuries in the realm of the elves and thus missing the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in Walter Map's 12th century De nugis curialium. The origin of the name Herla would be erilaz ("earl", Old Saxon erl), also found in the name of the Heruli (so that German erl-könig would literally correspond to earl-king)

Alternative suggestions have also been made; in 1836, Halling suggested a connection with a Turkic and Mongolian god of death or psychopomp, known as Erlik Chan.[9]

In German romantic literature

The Erlking's Daughter

Johann Gottfried von Herder introduced this character into German literature in "Erlkönigs Tochter", a ballad published in his 1778 volume Stimmen der Völker in Liedern. It was based on the Danish folk ballad "Hr. Oluf han rider" "Sir Oluf he rides" published in the 1739 Danske Kæmpeviser.[4] Herder undertook a free translation where he translated the Danish elvermø ("elf maid") as Erlkönigs Tochter; according to Danish legend old burial mounds are the residence of the elverkonge, dialectically elle(r)konge, the latter has later been misunderstood in Denmark by some antiquarians as "alder king", cf Danish elletræ "alder tree". It has generally been assumed that the mistranslation was the result of error, but it has also been suggested (Herder does actually also refer to elves in his translation) that he was imaginatively trying to identify the malevolent sprite of the original tale with a woodland old man (hence the alder king).[10]

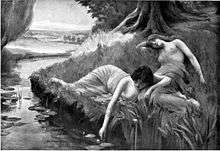

The story portrays Sir Oluf riding to his marriage but being entranced by the music of the elves. An elf maiden, in Herder's translation the Elverkonge's daughter, appears and invites him to dance with her. He refuses and spurns her offers of gifts and gold. Angered, she strikes him and sends him on his way, deathly pale. The following morning, on the day of his wedding, his bride finds him lying dead under his scarlet cloak.[4]

Goethe's Erlkönig

Although inspired by Herder's ballad, Goethe departed significantly from both Herder's rendering of the Erlking and the Scandinavian original. The antagonist in Goethe's "Der Erlkönig" is the Erlking himself rather than his daughter. Goethe's Erlking differs in other ways as well: his version preys on children, rather than adults of the opposite sex, and the Erlking's motives are never made clear. Goethe's Erlking is much more akin to the Germanic portrayal of elves and valkyries – a force of death rather than simply a magical spirit.[4]

Reception in English literature

In Angela Carter's short story "The Erl-King", contained within the 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber, the female protagonist encounters a male forest spirit. Though she becomes aware of his malicious intentions, she is torn between her desire for him and her desire for freedom. In the end, she forms a plan to kill him in order to escape his power.

Charles Kinbote, the narrator of Vladimir Nabokov's 1962 novel, Pale Fire, alludes to "alderkings". One allusion is in his commentary to line 275 of fellow character John Shade's eponymous poem. In the case of this commentary, the word invokes homosexual ancestors of the last king of Zembla, Kinbote's ostensible homeland. The novel contains at least one other reference by Kinbote to alderkings.

In Jim Butcher's The Dresden Files, there is a character called the Erlking, modeled after the leader of the Wild Hunt, Herne the Hunter.

In the author John Connolly's short story collection Nocturnes (2004), there is a character known as the Erlking who attempts to abduct the protagonist.

J.K. Rowling's Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them lists a creature named an Erkling, very similar to the Erlking, as one of the many that inhabit the Wizarding World. Erklings are also present in the videogame Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, set in the same universe.

The New Yorker's "20 Under 40" issue of July 5, 2010 included the short story "The Erlking" by Sarah Shun-lien Bynum.

References

- Harper, Douglas. "Erl-king". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Das Kloster vol. 9 (1848), p. 171

- Lorraine Byrne, Schubert's Goethe Settings, pp. 222-228.

- Joep Leerssen, "On the Celtic Roots of a Romantic Theme", in Configuring Romanticism: Essays Offered to C.C. Barfoot, p.3. Rodopi, 2003. ISBN 90-420-1055-X

- New Oxford American Dictionary (second ed.). Oxford University Press. 2005.

-

- Harper, Douglas. "harlequin". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Karl Halling, "Orientalisch, besonders persischer Ursprung deutscher Sagen", Anzeiger für Kunde der deutschen Vorzeit: Organ d. Germanischen Museums. Germanisches Museum. 1836. p. 64.

- John R. Williams, The Life of Goethe: A Critical Biography, pp. 86-88. Blackwell Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-631-23173-0