Entremets

Entremets (/ˈɑːntrəmeɪ/; French: [ɑ̃tʁəmɛ]; from Old French, literally meaning "between servings") in French cuisine historically referred to small dishes served between courses but in modern times more commonly refers to a type of dessert. Originally it was an elaborate form of entertainment dish common among the nobility and upper middle class in Europe during the later part of the Middle Ages and the early modern period. An entremet marked the end of a serving of courses and could be anything from a simple frumenty (a type of wheat porridge) that was brightly colored and flavored with exotic and expensive spices to elaborate models of castles complete with wine fountains, musicians, and food modeled into allegorical scenes. By the end of the Middle Ages, it had evolved almost entirely into dinner entertainment in the form of inedible ornaments or acted performances, often packed with symbolism of power and regality. In English it was more commonly known as a subtlety (also sotelty or soteltie) and did not include acted entertainment.

| Part of a series on |

| Meals |

|---|

|

| Meals |

| Components and courses |

| Related concepts |

History

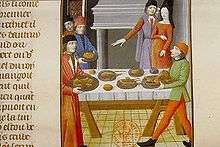

Dishes that were intended to be eaten as well as entertain can be traced back at least to the early Roman Empire. In his Satyricon, the Roman writer Petronius describes a dish consisting of a rabbit dressed to look like the mythical horse Pegasus.[1] The function of the entremets was to mark the end of a course, mets (a serving of several dishes), of which there could be several at a banquet. It punctuated each stage of a banquet, prepared the diners for the next serving and functioned as a conversation piece. The earliest recipe for an entremets can be found in an edition of Le Viandier, a medieval recipe collection from the early 14th century. It described a comparatively simple dish: boiled and fried chicken liver with chopped giblet, ground ginger, cinnamon, cloves, wine, verjuice, beef bouillon and egg yolks, served with cinnamon on top, and was supposed to be of a bright yellow color. An even simpler dish, like millet boiled in milk and seasoned with saffron, was also considered to be an entremets.[2]

The most noticeable trait of the early entremets was the focus on vivid colors. Later on, the entremets would take the shape of various types of illusion foods, such as peacocks or swans that were skinned, cooked, seasoned and then redressed in their original plumage (or filled with the meat of tastier fowl) or even scenes depicting contemporary human activities, such as a knight in the form of a grilled capon equipped with a paper helmet and lance, sitting on the back of a roast piglet.[3] Elaborate models of castles made from edible material was a popular theme. At a feast in 1343 dedicated to Pope Clement VI, one of the Avignon popes, one of the entremets was a castle with walls made from roast birds, populated with cooked and redressed deer, wild boar, goat, hare and rabbit.[4]

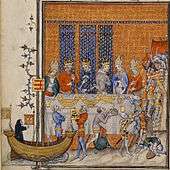

In the 14th century entremets began to involve not just eye-catching displays of amusing haute cuisine, but also more prominent and often highly symbolic forms of inedible entertainment. In 1306, the knighting of the son of Edward I included performances of chansons de geste in what has been assumed to be part of the entremets.[5] During the course of the 14th century they would often take on the character of theatrical displays, complete with props, actors, singers, mummers and dancers. At a banquet held in 1378 by Charles V of France in honor of Emperor Charles IV, a huge wooden model of the city of Jerusalem was rolled in before the high table. Actors portraying the crusader Godfrey of Bouillon and his knights then sailed into the hall on a miniature ship and reenacted the capture of Jerusalem in 1099.[6]

From the late 14th century on in England, entremets are referred to as subtleties. This English term was derived from an older meaning of "subtle" as "clever" or "surprising".[7] The meaning of "subtlety" did not include entertainment involving actors; those were referred to as pageants.[8] The "four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie", in the nursery rhyme "Sing a Song of Sixpence", has its genesis in an entremets presented to amuse banquet guests in the 14th century. This extravaganza of hospitality was related by an Italian cook of the era.[9] “Live birds were slipped into a baked pie shell through a hole cut in its bottom.” The unwary guest would release the flapping birds once the upper crust was cut into.[10]

At the end of the Middle Ages, the level of refinement among the noble and royal courts of Europe had increased considerably, and the demands of powerful hosts and their rich dinner guests resulted in ever more complicated and elaborate creations. Chiquart, cook to Amadeus VIII, Duke of Savoy, described an entremets entitled Castle of Love in his 15th-century culinary treatise Du fait de cuisine ("On cookery"). It consisted of a giant castle model with four towers, carried in by four men. The castle contained, among other things, a roast piglet, a swan cooked and redressed in its own plumage, a roast boar's head and a pike cooked and sauced in three different ways without having been cut into pieces, all of them breathing fire.[11] The battlements of the castle were adorned with the banners of the Duke and his guests, manned by miniature archers, and inside the castle there was a fountain that gushed rosewater and spiced wine.[12] Noteworthy for its entertainment value to the assembled nobles of the time, the 17th century provided a memorable banquet event courtesy of the host, the Duke of Buckingham. In honor of his royal guests, Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria, a pie was prepared concealing a human being — famous dwarf of the era, Jeffrey Hudson. [13]

Entremets also made an effective tool for political displays. One of the most famous examples is the so-called Feast of the Pheasant, arranged by Philip the Good of Burgundy in 1454. The theme of the banquet was the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, and included a vow by Philip and his guests to retake the city in a crusade, though this was never realized. There were several spectacular displays at the banquet referred to by contemporary witnesses as entremets. Guests were entertained by a wide range of extravagant displays of automatons in the form of fountains and pies containing musicians. At the end of the banquet, an actor representing the Holy Church rode in on an elephant and read a poem about the plight of Eastern Christianity under Ottoman rule.[8]

See also

- Entremés

- Hors d'oeuvre – Food items served before the main courses of a meal

- Intermezzo (disambiguation)

- Medieval cuisine – Foods, eating habits, and cooking methods of various European cultures during the Middle Ages

- Pièce montée

- Pop out cake

References

- Scully (1995) p. 107.

- Scully (1995) p. 105.

- Scully (1995), pp. 105-107.

- Adamson (2004), p. 114.

- Strong (2003), pp. 121-123.

- Henisch (1976), p. 234.

- Constance B. Hieatt "Medieval Britain" p. 35, in Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe.

- Adamson (2004), p. 166.

- Giovanni de Roselli's Epulario, quale tratta del modo de cucinare ogni carne, uccelli, pesci... (1549), of which an English translation, Epulario, or the Italian Banquet, was published in 1598 (Mary Augusta Scott, Elizabethan Translations from the Italian no. 256, p. 333f.).

- Jenkins, Jessica Kerwin, The Encyclopedia of the Exquisite, Nan A. Talese/Doubleday,2010, p. 200-01

- The effect was created by placing wax candles bound with strips of cotton that had been soaked in alcohol in the mouth of the animals and lighting them; Scully (1995), p. 162.

- Du Fait de Cuisine. Translation by Elizaebth Cook. Retrieved on October 10, 2008.

- Jenkins, Jessica Kerwin, The Encyclopedia of the Exquisite, Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2010, p. 201

- Bibliography

- Adamson, Melitta Weiss Food in Medieval Times. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT. 2004 ISBN 0-313-32147-7

- Henisch, Bridget Ann Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society. The Pennsylvania State Press, University Park. 1976 ISBN 0-271-01230-7

- Regional Cuisines of Medieval Europe: A Book of Essays edited by Melitta Weiss Adamson (editor). Routledge, New York. 2002 ISBN 0-415-92994-6

- Scully, Terence The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge. 1995 ISBN 0-85115-611-8

- Strong, Roy Feast: A History of Grand Eating. Pimlico, London. 2003 ISBN 0-7126-6759-8

External links

| Look up entremets or subtlety in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Entremets. |

- How to Cook Medieval - A guide on how to make medieval cuisine and subtleties with modern ingredients

- Wikibooks Cookbook