Le Viandier

Le Viandier (often called Le Viandier de Taillevent, pronounced [lə vjɑ̃dje də tajvɑ̃]) is a recipe collection generally credited to Guillaume Tirel, alias Taillevent. However, the earliest version of the work was written around 1300, about 10 years before Tirel's birth. The original author is unknown, but it was common for medieval recipe collections to be plagiarized, complemented with additional material and presented as the work of later authors.

Le Viandier is one of the earliest and best-known recipe collections of the Middle Ages, along with the Latin Liber de Coquina (early 14th century) and the English Forme of Cury (c. 1390). Among other things, it contains the first detailed description of an entremet.

Manuscripts

There are four extant manuscripts of Le Viandier.[1] The oldest, found in the Archives cantonales du Valais (Sion, Switzerland), was written in the late 13th or very early 14th century, and was largely overlooked until the 1950s.[2] It is this manuscript that calls into question the authorship of Tirel, but a portion of it is missing at the beginning, so the title and author given for this earlier work are unknown.[1][2] A manuscript from the 14th century housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris), was formerly thought to be the oldest.[3] The version in the Biblioteca Vaticana (Vatican City), is from the early 15th century. The fourth extant version is in the Bibliothèque Mazarine (Paris) and also dates to the 15th century.

There was a fifth version from the 15th century in Saint-Lô, in the Archives de la Manche. It was mentioned by Jérôme Pichon and Georges Vicaire in their 1892 monograph, Le Viandier;[3] however, the Saint-Lô manuscript was destroyed by fire on 6 June 1944 during the invasion of Normandy.[1]

In the Valais manuscript there are about 130 recipes.[2] There are variations from manuscript to manuscript, both in their original form and in what has been preserved or lost over the centuries.

Haute Cuisine

Le Viandier was one of the first "haute cuisine" cookbooks, offering a framework for its preparation and presentation at table. Taillevent was a master cook to Charles V, which gave him extensive experience in serving French nobility. Taillevent divided the book into various sections, including sections specific to the preparation of meats, entremets, fish, sauces, and other recipes. Taillevent also goes into detail on the spices that should be used for various dishes. According to Taillevent, there are three themes in haute cuisine; the use of spices, the separation of preparation for the meat and fish dishes from the sauces, and the way a dish should be presented. These were all carefully outlined in Le Viandier. To further this idea of "medieval haute cuisine", Taillevent also mentions how much emphasis was placed on presentation by noting that often dyes were used to color sauces and meat roasts were covered with gold and silver leaves.[4]

Print

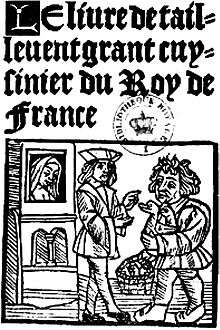

About 1486, Le Viandier went into print without a title-page date or place, but this was undoubtedly Paris. The 1486 version contained an additional 142 recipes not found in the manuscripts.[2] Twenty-four editions were produced between 1486 and 1615.

See also

- Apicius – a collection of Roman cookery recipes.

- Liber de Coquina – one of the oldest medieval cookbooks.

- Medieval cuisine

- The Forme of Cury – an extensive collection of medieval English recipes.

References

- Scully, Terence, ed. (1988). "Introduction". Le viandier de Guillaume Tirel dit Taillevent. University of Ottawa Press. ISBN 0-7766-0174-1.; Scully 1988 is the first edition to collate all four extant manuscripts; an English translation of the 220 recipes is included.

- Hyman, Mary and Philip Hyman, ed. (2003). "Preface". Le Viandier d'apres l'edition de 1486 (in French). Editions Manucius. ISBN 978-2845780248.

- Pichon, Jerome; Vicaire, Georges (1892). "Introduction". Le Viandier de Guillaume Tirel dit Taillevent (in French). p. iv.

- Trubek, Amy B. (2000). Haute Cuisine: How the French Invented the Culinary Profession. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 4–6. ISBN 9780812217766.