English embroidery

English embroidery includes embroidery worked in England or by English people abroad from Anglo-Saxon times to the present day. The oldest surviving English embroideries include items from the early 10th century preserved in Durham Cathedral and the 11th century Bayeux Tapestry, if it was worked in England. The professional workshops of Medieval England created rich embroidery in metal thread and silk for ecclesiastical and secular uses. This style was called Opus Anglicanum or "English work", and was famous throughout Europe.[2]

With the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, the focus of English embroidery increasingly turned to clothing and household furnishings, leading to another great flowering of English domestic embroidery in the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. The end of this period saw the rise of the formal sampler as a record of the amateur stitcher's skills. Curious fashions of the mid-17th century were raised work or stumpwork, a pictorial style featuring detached and padded elements,[3] and crewel work, featuring exotic leaf motifs worked in wool yarn.[4]

Canvaswork, in which thread is stitched through a foundation fabric, and surface embroidery, in which the majority of the thread sits on top of the fabric, exist side-by-side in the English tradition, coming in and out of fashion over the years. In the 19th century, the craze for Berlin wool work, a canvaswork style using brightly coloured wool, contrasts with art needlework, associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, which attempted to resurrect the artistic and expressive styles of medieval surface embroidery under the influence of the Gothic Revival and the Pre-Raphaelites.[5]

Although continental fashions in needlework were adopted in England, a number of popular styles were purely English in origin, including the embroidered linen jackets of the turn of the 17th century, stumpwork, and art needlework.[3]

Medieval period

Anglo-Saxon

Little physical evidence survives to reconstruct the early development of English embroidery before the Norman Conquest of 1066. Stitches reinforcing the seams of a garment in the Sutton Hoo ship burial may have been intended as decoration, and so be classed as embroidery, and fragments of a scrolling border worked in stem stitch were recovered from a grave in Kempston, Bedfordshire.[6] Some embroidered pieces of about 850 preserved in Maaseik, Belgium, are generally assumed to be Anglo-Saxon work based on their similarity to contemporary manuscript illustrations and sculptures of animals and interlace.[7][8]

The documentary evidence is rather richer than the physical remains. Part of the reason for both these facts is the taste among the late Anglo-Saxon elite for embroidering using lavish amounts of precious metal thread, especially gold, which both gave items a magnificence and expense worth recording, and meant that they were well worth burning to recover the bullion. Three old vestments, almost certainly Anglo-Saxon, recycled in this way at Canterbury Cathedral in the 1370s, produced over £250 of gold – a huge amount.[9] Richly embroidered hangings were used in both churches and the houses of the rich, but vestments were the most richly embellished of all, of a "particularly English" richness.[10] Most of these were sent back to Normandy or burnt for their metal after the Norman conquest. An image of part of a huge gold acanthus flower on the back of a gold-bordered chasuble, almost certainly depicting a specific real vestment, can be seen in the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold (fol. 118v).[11]

Scholars agree that three embroidered items from the coffin of St Cuthbert in Durham are Anglo-Saxon work, based on an inscription describing their commission by Queen Ælfflæd between 909 and 916.[12] These include a stole and maniple ornamented with figures of prophets outlined in stem stitch and filled with split stitch, with halos in gold thread worked with underside couching.[13] The quality of this silk embroidery on a gold background is "unparalleled in Europe at this time."[7]

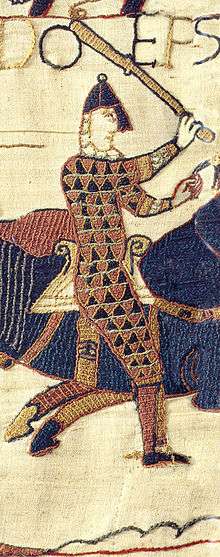

Scholarly consensus favours an Anglo-Saxon, probably Kentish origin for the Bayeux Tapestry. This famous narrative of the Conquest is not a true woven tapestry but an embroidered hanging worked in wool yarn on a tabby-woven linen ground using outline or stem stitch for lettering and the outlines of figures, and couching or laid work for filling in figures.[2][14][15]

Opus Anglicanum

The Anglo-Saxon embroidery style combining split stitch and couching with silk and goldwork in gold or silver-gilt thread of the Durham examples flowered from the 12th to the 14th centuries into a style known to contemporaries as Opus Anglicanum or "English work". Opus Anglicanum was made for both ecclesiastical and secular use on clothing, hangings, and other textiles. It was usually worked on linen or dark silks, or later, worked as individual motifs on linen and applied to velvet.[2][16]

Throughout this period, the designs of embroidery paralleled fashions in manuscript illumination and architecture. Work of this period often featured continuous light scrolls and spirals with or without foliations, in addition to figures of kings and saints in geometrical frames or Gothic arches.[2][16]

Opus Anglicanum was famous throughout Europe. A "Gregory of London" was working in Rome as a gold-embroiderer to Pope Alexander IV in 1263, and the Vatican inventory in Rome of 1295 records well over 100 pieces of English work.[2] Notable surviving examples of Opus Anglicanum include Syon Cope and the Butler-Bowden Cope of 1330–50 in the Victoria and Albert Museum, embroidered with silver and silver-gilt thread and coloured silks on silk velvet, which was disassembled and later reassembled into a cope in the 19th century.

Professional embroiderers

By the 13th century, most English goldwork was made in London workshops, which produced ecclesiastical work, clothing and furnishings for royalty and the nobility, heraldic banners and horse-trappings, and the ceremonial regalia for the great Livery Companies of the City of London and for the court.[17][18][19]

The founding of the embroiderer's guild in London is attributed to the 14th century or earlier, but its early documents were lost in the Great Fire of London in the 17th century. An indenture of 23 March 1515 records the establishment of Broderers' Hall in Cutter Lane in that year,[20] and the guild was officially incorporated (or reincorporated) by Royal Charter under Elizabeth I in 1561 as the Worshipful Company of Broderers.[21] Professional embroiderers were also attached to the great households of England, but it is unlikely that those working far from London were members of the Company.[19]

From the middle of the 14th century, money that had previously been spent on luxury goods like lavish embroidery was redirected to military expenditure, and imported Italian figured silks competed with native embroidery traditions. Varieties of design in textiles succeeded each other very rapidly, and they were more readily available than the more leisurely produced needlework. The work produced by the London workshops was simplified to meet the demands of this deteriorating market. The new techniques required less work and smaller quantities of expensive materials. Surface couching replaced underside couching, and allover embroidery was replaced by individual motifs worked on linen and then applied to figured silks or silk velvets.[2] Increasingly, designs for embroidery were derived directly from woven patterns, "thus losing not only their former individuality and richness, but also their former ... story-telling interest."[22]

Renaissance to Restoration

The second great flowering of English embroidery, after Opus Anglicanum, took place in the reign of Elizabeth I.[23]

Although the majority of surviving English embroidery from the medieval period was intended for church use, this demand decreased radically with the Protestant Reformation. In contrast, the bulk of the surviving embroidery of the Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean eras is for domestic use, whether for clothing or household decoration. The stable society that existed between the accession of Elizabeth in 1558 and the English Civil War encouraged the building and furnishing of new houses, in which rich textiles played a part. Some embroidery was imported in this period, including the canvas work bed valances once thought to be English but now attributed to France, but the majority of work was made in England—and increasingly, by skilled amateurs, mostly women, working domestically, to designs by professional men and women, and later to published pattern books.[24]

Tudor and Jacobean styles

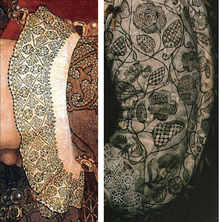

A general taste for abundant surface ornamentation is reflected in both household furnishings and in fashionable court clothing from the mid-16th century through the reign of James I. A 1547 account of the wardrobe of Henry VIII shows that just over half of the 224 items were ornamented with embroidery of some kind,[25] and embroidered shirts and accessories were popular New Year's gift to the Tudor monarchs.[26] Fine linen shirts, chemises, ruffs, collars, coifs and caps were embroidered in monochrome silks and edged in lace. The monochrome works are classified as blackwork embroidery even when worked in other colours; red, crimson, blue, green, and pink were also popular.[26][27]

Outer clothing and furnishings of woven silk brocades and velvets were ornamented with gold and silver embroidery in linear or scrolling patterns, applied bobbin lace and passementerie, and small jewels.[25][27][28]

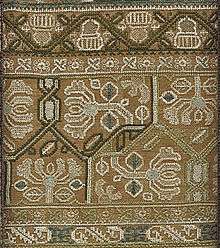

Appliqué work was popular in the Tudor era, especially for large-scale works such as wall hangings. In Medieval England, rich clothing had been bequeathed to the church to be remade into vestments; following the dissolution of the monasteries at the Reformation, the rich silks and velvets of the great monastic houses were cut up and repurposed to make hangings and cushions for private homes.[23] Shapes cut from opulent fabrics and small motifs or slips worked on fine linen canvas were applied a background fabric of figured silk, velvet, or plain wool and embellished with embroidery, in a style deriving from the later, simpler forms of Medieval work.[27]

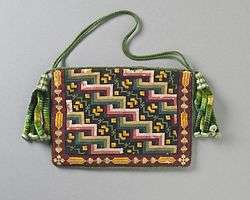

Canvaswork in which the linen ground was covered entirely by tent, gobelin, or cross stitches in wool or silk thread was often used for cushion covers and small bags. Notable examples like the Bradford carpet, a pictorial table cover, were likely the work of professionals in the Broderers' Company.[19]

Polychrome (multicoloured) silk embroidery became fashionable in the reign of Elizabeth, and from c. 1590 to 1620 a uniquely English fashion arose for embroidered linen jackets worn informally or as part of masquing costume. These jackets usually featured scrolling floral patterns worked in a multiplicity of stitches. Similar patterns worked in 2-ply worsted wool called crewel on heavy linen for furnishings are characteristic of Jacobean embroidery.[27]

Pattern sources

Pattern books for geometric embroidery and needlelace were published in Germany as early as the 1520s. These featured the stepped, angular patterns characteristic of early blackwork, ultimately deriving from medieval Islamic Egypt. These patterns, seen in the portraits of Hans Holbein the Younger, were worked over counted threads in a double running stitch (later called Holbein stitch by English embroiderers).[29]

The first pattern book for embroidery published in England was Moryssche & Damaschin renewed & encreased very popular for Goldsmiths & Embroiderers by Thomas Geminus (1545). Moryssche or Moresque refers to Moorish or arabesque designs of spirals, scrolls, and zigzags,[30] an important part of the repertoire of Renaissance ornament in many media. Scrolling patterns of flowers and leaves filled with geometric filling stitches are characteristic of blackwork from the 1540s through 1590s, and similar patterns worked in coloured silks appear from the 1560s, outlined in backstitch and filled with detached buttonhole stitch.[30]

Additional pattern books for embroiderers appeared late in the century, followed by Richard Shorleyker's A Schole-house for the Needle published in London in 1624.[30] Other sources for embroidery designs were the popular herbals and emblem books. Both domestic and professional embroiderers probably relied on skilled draughtsmen or pattern-drawers to interpret these design sources and draw them out on linen ready to be stitched.[31]

Early samplers

Printed pattern books were not easily obtainable, and a sampler or embroidered record of stitches and patterns was the most common form of reference. 16th-century English samplers were stitched on a narrow band of fabric and totally covered with stitches. These band samplers were highly valued, often being mentioned in wills and passed down through the generations. These samplers were stitched using a variety of needlework styles, threads, and ornament.

The earliest dated surviving sampler, housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum, was made by Jane Bostocke who included her name and the date 1598 in the inscription, but the earliest documentary reference to sampler making goes back another hundred years, to the 1502 household expense accounts of Elizabeth of York, which record the purchase of an ell of linen to make a sampler for the queen.[32]

From the early 17th century, samplers became a more formal and stylized part of a girl's education, even as the motifs and patterns on the samplers faded from fashion.

Pictorial embroidery and stumpwork

.jpg)

Following the death of James I and the accession of Charles I, elaborately embroidered clothing faded from popularity under the dual influences of rising Puritanism and the new court's taste for French fashion with its lighter silks in solid colours accessorised with masses of linen and lace.[33] In this new climate, needlework was praised by moralists as an appropriate occupation for girls and women in the home, and domestic embroidery for household use flourished. Embroidered pictures, mirror frames, workboxes, and other domestic objects of this era often depicted Biblical stories featuring characters dressed in the fashion of Charles and his queen Henrietta Maria, or after the Restoration, Charles II and Catherine of Braganza.

These stories were executed in canvaswork or in coloured silks in a uniquely English style called raised work, usually known by its modern name stumpwork.[34] Raised work arose from the detached buttonhole stitch fillings and braided scrolls of late Elizabethan embroidery. Areas of the embroidery were worked on white or ivory silk grounds in a variety of stitches and prominent features were padded with horsehair or lambswool, or worked around wooden shapes or wire frames. Ribbons, spangles, beads, small pieces of lace, canvaswork slips, and other objects were added to increase the dimensionality of the finished work.[3][33]

Crewel

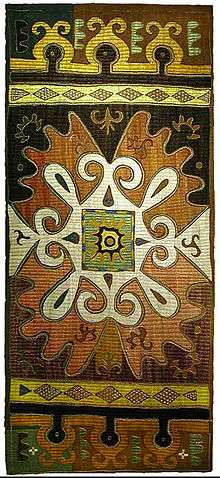

Sets of bed hangings embroidered in crewel wools were another characteristic product of the Stuart era. These were worked on a new fabric, a natural twill weave from Bruges with a linen warp and cotton weft. Crewel wools of the 17th century were firmly twisted unlike the soft wools sold under that name today, and were dyed in deep rich shades of green, blue, red, yellow, and brown. Motifs of flowers and trees, with birds, insects, and animals, were worked at large scale in a variety of stitches. The origins of this work are in the polychrome embroidery on scrolling stems of the Elizabethan era, later blended with the Tree of Life and other motifs of Indian palampores, introduced by the trade of the East India Company.[4][35]

After the Restoration, the patterns became ever more fanciful and exuberant. "It is an almost impossible task to describe the large leaves, since they bear no resemblance to anything natural, they are, however, rarely angular in outline, rejoicing rather in sweeping curves, and drooping points, curled over to display the under side of the leaf, a device that gave opening for much ingenuity in the arrangement of the stitches."[4]

Although usually called "Jacobean embroidery" by modern stitchers, crewel has its origins in the reign of James I but remained popular through the reign of Queen Anne and into the early 18th century, when a return to the simpler forms of the earliest work became fashionable.[4]

Glorious Revolution to the Great War

Later Stuart

The accession of William III and Mary II following the Glorious Revolution of 1688 triggered another change in needlework fashions. Associations of stumpwork with the reign of the deposed Stuarts combined with Mary's Dutch taste ushered in new styles influenced by Indian chintzes. From the 1690s, household furnishings such as chair covers and firescreens were the focus of embroidery in the home.[36]

Georgian

In the Georgian era, canvaswork was popular for chair coverings, footstools, screens and card tables. Embroidered pictures and upholstery both reflected the popular pastoral theme of men and women in the sheep-cropped English countryside. Other recurring themes include exotic Tree of Life patterns influenced by earlier crewelwork and chinoiserie with its fanciful imagery of an imaginary China, asymmetry in format and whimsical contrasts of scale. In contrast, needlepainting in silks and wools produced naturalistic portraits and domestic scenes.[37][38]

Embroidery was once again an important element of fashion in the early 18th century. Aprons, stomachers, hanging pockets, shoes, gowns, and men's coats and waistcoats were all decorated with embroidery.[37]

Later samplers

By the 18th century, sampler making had become an important part of girls' education in boarding and institutional schools. A commonplace component was now an alphabet with numerals, possibly accompanied by various crowns and coronets, all used in marking household linens. Traditional embroidered motifs were now rearranged into decorative borders framing lengthy inscriptions or verses of an "improving" nature and small pictorial scenes. These new samplers were more useful as a record of accomplishment to be hung on the wall than as a practical stitch guide.[39]

Tambourwork

Tambourwork was a new chainstitch embroidery fad of the 1780s influenced by Indian embroidered muslins. Stitched originally with a needle and later with a small hook, tambour takes its name from the round embroidery frame in which it was worked. Tambour was suited to the light, flowing ornament appropriate to the new muslin dresses of this period, and patterns were readily available in periodicals like the Lady's Magazine which debuted in 1770.[40][41]

Tambourwork was copied by machine early in the Industrial Revolution. As early as 1810, a "worked muslin cap ... done in tambour stitch by a steam-engine" was on the market, and machine-made netting was in general use as a background by the 1820s.[42]

Smocking

The linen smock-frocks worn by rural workers, especially shepherds and waggoners, in parts of England and Wales from the early eighteenth century featured fullness across the back, breast, and sleeves folded into "tubes" (narrow unpressed pleats) held in place and decorated by smocking, a type of surface embroidery in a honeycomb pattern across the pleats that controls the fullness while allowing a degree of stretch.

Embroidery styles for smock-frocks varied by region, and a number of motifs became traditional for various occupations: wheel-shapes for carters and wagoners, sheep and crooks for shepherds, and so on. Most of this embroidery was done in heavy linen thread, often in the same color as the smock.

By the mid-nineteenth century, wearing of traditional smock-frocks by country laborers was dying out, and a romantic nostalgia for England's rural past led to a fashion for women's and children's clothing loosely styled after smock-frocks. These garments are generally of very fine linen or cotton and feature delicate smocking embroidery done in cotton floss in contrasting colors; smocked garments with pastel-colored embroidery remain popular for babies.[43]

Berlin work

In the early 19th century, canvaswork in tent or petit point stitch again became popular. The new fashion, using printed patterns and coloured tapestry wools imported from Berlin, was called Berlin wool work. Patterns and wool for Berlin work appeared in London in 1831.[44] Berlin work was stitched to hand-coloured or charted patterns, leaving little room for individual expression, and was so popular that "Berlin work" became synonymous with "canvaswork". Its chief characteristic was intricate three-dimensional looks created by careful shading. By mid-century, Berlin work was executed in bright colours made possible by the new synthetic dyes. Berlin work was very durable and was made into furniture covers, cushions, bags, and slippers as well as for embroidered "copies" of popular paintings. The craze for Berlin work peaked around 1850 and died out in the 1870s, under the influence of a competing aesthetic that would become known as art needlework.[5][44]

Art needlework

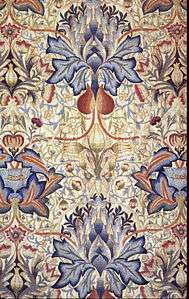

In 1848, the influential Gothic Revival architect G. E. Street co-wrote a book called Ecclesiastical Embroidery. He was a staunch advocate of abandoning faddish Berlin work in favour of more expressive embroidery techniques based on Opus Anglicanum.[45] Street's one-time apprentice, the Pre-Raphaelite poet, artist, and textile designer William Morris, embraced this aesthetic, resurrecting the techniques of freehand surface embroidery which had been popular from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. The new style, called art needlework, emphasized flat patterns with delicate shading in satin stitch accompanied by a number of novelty stitches. It was worked in silk or wool thread dyed with natural dyes on wool, silk, or linen grounds.

By the 1870s, Morris's decorative arts firm Morris & Co. was offering both designs for embroideries and finished works in the art needlework style. Morris became active in the growing movement to return originality and mastery of technique to embroidery. Morris and his daughter May were early supporters of the Royal School of Art Needlework, founded in 1872, whose aim was to "restore Ornamental Needlework for secular purposes to the high place it once held among decorative arts."[46]

Textiles worked in art needlework styles were featured at the various Arts and Crafts exhibitions from the 1890s to the Great War.[47]

Modern period

Organizations whose origins date back as far as the Middle Ages remain active in supporting embroidery in Britain today.

The Worshipful Company of Broderers is now a charitable organization supporting excellence in embroidery.[48]

The Royal School of Needlework is based at Hampton Court Palace and is engaged in textile restoration and conservation, as well as training professional embroiderers through a new 2-year Foundation Degree programme (in conjunction with the University for the Creative Arts) with a top-up to full BA(Hons) being available for the first time in the 2011/12 academic year. Previously, apprentices were trained by an intensive 3-year in-house programme.[49] It is a registered charity and receives commissions from public bodies and individuals, including the Hastings Embroidery of 1965 commemorating the 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings the following year, and the Overlord Embroidery of 1968–74 commemorating the D-Day invasion of France during World War II, now in The D-Day Story in Southsea, Portsmouth.

The Embroiderers' Guild, also based at Hampton Court, was founded in 1906 by sixteen former students of the Royal School of Art Needlework to represent the interests of embroidery. It is active in education and exhibition.[50]

Notes

- Beck 1992, pp. 44–44

- Levey and King 1993, p. 12

- Embroiderers' Guild 1984, p. 81

- Fitwzwilliam and Hand 1912, "Introduction"

- Embroiderers' Guild 1984, p. 54

- Coatsworth, Elizabeth: "Stitches in Time: Establishing a History of Anglo-Saxon Embroidery", in Netherton and Owen-Crocker 2005, pp. 6–7

- Levey and King 1993, p. 11

- The Maaseik Embroideries, details and photos from Historical needlework resources.

- Dodwell, p. 181

- Dodwell, p. 182

- Dodwell, pp. 129–145, 174–187, and Plate D.

- Maniple and Stole of St Cuthbert details and photos from Historical needlework resources.

- Coatsworth 2005, p. 16

- Coatsworth 2005, pp. 22–23

- Wilson 1985, pp.201–227

- Jourdain 1912, pp. 6–8

- Lemon, 2004

- Jourdain 1912, pp. 13–15

- Levey and King 1993, p. 17

- Norris p. 225

- Jourdain 1912, p. 56

- Jourdain 1912, p. 15

- Digby 1964, p. 21

- Levey and King 1993, pp. 13 and 15

- Hayward 2007, p. 360–361

- Arnold 2008, p. 9

- Levey 1993, pp. 16–17

- Arnold 1985, pp. PAGES

- Arnold 2008, p. 6

- North, Susan. "'An Instrument of profit, pleasure, and of ornament': Embroidered Tudor and Jacobean Dress Accessories." In Morrall and Watt 2008, p. 43–47

- Digby 1984, pp. 51–52

- Fawdry and Brown, p. 16

- Gueter, Ruth. "Embroidered Biblical Narratives and Their Social Context." In Morrall and Watt 2008, p. 43–47

- Hughes, p.22

- Beck 1995, pp. 54–58

- Geuter, p. 73

- Beck 1995, pp. 63–83

- Hughes, p. 37

- Beck 1995, p. 70

- Beck 1995, pp. 86–87

- Hughes, pp. 41, 80

- Hughes, p.80

- Marshall 1980, pp. 17–19

- Berman 2000

- Parry 1983, pp. 10–11.

- Quoted in Parry 1983, pp. 18–19.

- Parry, Linda. "Textiles". In Lochnan, Schoenherr, and Silver 1996, p. 156

- "Worshipful Company of Broderers official site". Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- "Royal School of Needlework official site". Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- "Embroiderers' Guild official site". Retrieved 2009-01-25.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Embroidery of England. |

- Arnold, Janet (1988). Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd. W S Maney and Son Ltd , Leeds. ISBN 0-901286-20-6.

- Arnold, Janet (November 2008). Patterns of Fashion 4: The Cut and Construction of Linen Shirts, Smocks, Neckwear, Headwear and Accessories for Men and Women C. 1540–1660. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-57082-1.

- Beck, Thomasina (1992). The Embroiderer's Flowers. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-9901-2.

- Beck, Thomasina (1995). The Embroiderer's Story. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-0238-8.

- Berman, Pat (2000). "Berlin Work". American Needlepoint Guild. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- Digby, George Wingfield (1964). Elizabethan Embroidery. Thomas Yoseloff.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1982). Anglo-Saxon Art, A New Perspective. Manchester UP (US edn. Cornell, 1985). ISBN 0-7190-0926-X.

- Embroiderers' Guild Practical Study Group (1984). Needlework School. QED Publishers. ISBN 0-89009-785-2.

- Fawdry, Marguerite; Deborah Brown (1980). The Book of Samplers. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-09006-4.

- Fitzwilliam,Ada Wentworth; A. F. Morris Hands (1912). Jacobean Embroidery. Kegan Paul.

- Gostelow, Mary (1976). Blackwork. Batsford; Dover reprint 1998. ISBN 0-486-40178-2.

- Hughes, Therle (n.d.). English Domestic Needlework 1660–1860. Abbey Fine Arts Press, London.

- Jourdain, Margaret (1912). English Secular Embroidery from Saxon to Tudor Times. The History of English Secular Embroidery. Dutton and Co. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- Lemon, Jane (2004). Metal Thread Embroidery. Sterling. ISBN 0-7134-8926-X.

- Levey, S. M.; D. King (1993). The Victoria and Albert Museum's Textile Collection Vol. 3: Embroidery in Britain from 1200 to 1750. Victoria and Albert Museum. ISBN 1-85177-126-3.

- Lochnan, Katharine A., Douglas E. Schoenherr, and Carole Silver (eds.) (1996). The Earthly Paradise: Arts and Crafts by William Morris and His Circle from Canadian Collections. Key Porter Books. ISBN 1-55013-450-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Marshall, Beverly (1980). Smocks and Smocking. Van Nostrand Rheinhold. ISBN 0-442-28269-9.

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors (2005). Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-123-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors (2006). Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 2. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-203-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Norris, Herbert (1997) [1938]. Tudor Costume and Fashion. J. M. Dent; Dover Publications (reprint). ISBN 0-486-29845-0.

- Parry, Linda (1983). William Morris Textiles. Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-77074-4.

- Todd, Pamela (2001). Pre-Raphaelites at Home. Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 0-8230-4285-5.

- Watt, Melinda; Andrew Morrall (2008). English Embroidery in the Metropolitan Museum 1575–1700: 'Twixt Art and Nature. Metropolitan Museum of Art with the Bard Graduate Centre for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design and Culture. ISBN 978-0-300-12967-0.

- Wilson, David M. (1985). The Bayeux Tapestry. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-25122-3.