Emirates Mars Mission

The Emirates Mars Mission (Arabic: مشروع الإمارات لاستكشاف المريخ) is a United Arab Emirates Space Agency uncrewed space exploration mission to Mars. The Hope (Arabic: مسبار الأمل, Al Amal) orbiter was launched on 19 July 2020 at 21:58:14 UTC.[3]

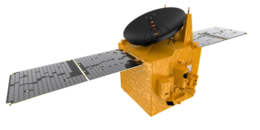

Artists' impression of the Hope spacecraft | |

| Mission type | Mars orbiter |

|---|---|

| Operator | Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre |

| COSPAR ID | 2020-047A |

| SATCAT no. | 45918 |

| Website | www |

| Mission duration | 28d 13h (since launch) 2 years (planned)[1] |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Hope (Arabic: الأمل, Al-Amal) |

| Manufacturer | |

| Launch mass | 1350 kg |

| Dry mass | 550 kg (+ 800 kg hydrazine fuel)[2] |

| Dimensions | 2.37 × 2.90 m |

| Power | 1800 watts from two solar panels |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 19 July 2020, 21:58:14 UTC[3] |

| Rocket | H-IIA |

| Launch site | Tanegashima, LP-1 |

| Contractor | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Periareon altitude | 20000 km[4] |

| Apoareon altitude | 43000 km |

| Inclination | Semi-synchronous orbit |

| Period | 55 hours |

| Epoch | Planned |

| Mars orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | February 2021 (planned)[3] |

| Instruments | |

| |

| |

The mission design, development, and operations are led by the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC).[5] The spacecraft was developed by MBRSC and the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado Boulder, with support from Arizona State University (ASU) and the University of California, Berkeley. It was assembled at the University of Colorado.[6][7]

The space probe will study daily and seasonal weather cycles, weather events in the lower atmosphere such as dust storms, and how the weather varies in different regions of the planet. It will also attempt to find out why it is losing hydrogen and oxygen into space and other possible reasons behind its drastic climate changes. The mission is being carried out by a team of Emirati engineers in collaboration with foreign research institutions, and is a contribution towards a knowledge-based economy in the UAE.[8] Hope is scheduled to reach Mars in February 2021.[9]

Hope was the first of three space missions sent toward Mars during the July 2020 Mars launch window, with missions also launched by the national space agencies of China (Tianwen-1) and the U.S. (Mars 2020). All three are expected to arrive at Mars in February 2021.

Overview

The idea for a UAE mission to Mars came from a UAE cabinet retreat at the end of 2013.[10] The mission was announced by Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the President of the United Arab Emirates, in July 2014,[11] and is aimed at enriching the capabilities of Emirati engineers and increasing human knowledge about the Martian atmosphere.[12]

The spacecraft orbiter is a mission to Mars to study the Martian atmosphere and climate. It was built by the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado Boulder with support from the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC), Arizona State University (ASU), and the University of California, Berkeley.[13][14][15] The Hope probe was launched from Japan by a Japanese H-IIA rocket, built and operated by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) in July 2020 and it will take seven months to arrive at Mars.[16][13] If successful, it would become the first mission to Mars by any West Asian, Arab or Muslim-majority country.

To accomplish the objectives of the Emirates Mars Mission, an agreement was signed between the United Arab Emirates Space Agency (UAESA) and MBRSC, under a directive given by Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai.[17] As per the agreement, the Emirates Mars Mission will be funded by the UAE Space Agency and it will also supervise the complete execution process for the Hope probe. The agreement outlines the financial and legal framework along with assigning a timeline for the entire project.[11] Under the agreement, MBRSC has been commissioned for the design and manufacture of the Hope probe.[11]

In designing and building the orbiter, the mission deputy project manager and science lead, Sarah Al Amiri, collaborated with LASP, UC Berkeley, and ASU.[14][15][18] The project manager is Omran Sharaf.[15]

The name Hope (Arabic: al-Amal) was chosen because "it sends a message of optimism to millions of young Arabs," according to Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum.[15] The resulting mission data will be shared freely with more than 200 institutions worldwide.[19]

The Hope probe is compact and cubic in shape and structure, with a mass of 1,350 kilograms (2,980 lb) including fuel. The probe is 2.37 metres (7 ft 9 in) wide and 2.90 metres (9 ft 6 in) long, equivalent to a small car. Hope uses two 900-watt solar panels to charge its batteries, and it communicates with Earth using a high-gain 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in)-wide dish antenna. The spacecraft is equipped with star tracker sensors which help determine its position in space by identifying the constellations in relation to the Sun. Six 120-N thrusters control the speed of the probe, and eight 5-N reaction control system (RCS) thrusters are responsible for delicate maneuvers.[20]

The expected travel time of the Hope probe is about 200 days on its journey of 493 million kilometres (306×106 mi).[21] Upon arrival, it will enter orbit and study the Martian atmosphere for two years while its instruments help build holistic models of it. The data is expected to provide additional data on the escape of the atmosphere to outer space.[22] The Hope probe will carry three scientific instruments to study the Martian atmosphere, which include a digital camera for high resolution coloured images, an infrared spectrometer which will examine the temperature profile, ice, water vapors in the atmosphere, and an ultraviolet spectrometer which will study the upper atmosphere and traces of oxygen and hydrogen further out into space.[23]

The mission is regarded as an investment in the UAE's economy and human capital. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum mentioned three messages when he announced the mission: "The first message is for the world: that Arab civilisation once played a great role in contributing to human knowledge, and will play that role again; the second message is to our Arab brethren: that nothing is impossible, and that we can compete with the greatest of nations in the race for knowledge and the third message is for those who strive to reach the highest of peaks: set no limits to your ambitions, and you can reach even to space."[24] The mission is timed to arrive at Mars before the fiftieth anniversary (2 December 2021) of the independence of the United Arab Emirates. According to the UAE's minister of cabinet affairs, Mohammad bin Abdullah Al Gergawi, the mission's cost is US$200 million.[25]

A prototype of the Hope spacecraft was displayed at the Dubai Airshow in November 2017. The prototype is a model built to give a general idea of what the spacecraft will look like.[26] Project manager Omran Sharaf said the mission is on track to launch in July 2020.[27] The spacecraft was successfully launch on a Mitsubishi H-IIA rocket from the Tanegashima Space Center near Minamitane, Japan at 6:58 a.m. local time on 20 July 2020.[25]

The 2020 International Astronautical Congress is to be held in October 2020 in Dubai, three months after the launch of the Hope Mars Mission.[28]

Scientific objectives

To decide on its science objectives, the EMM team consulted the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group, a NASA-led international forum that considers past and current Mars missions and identifies gaps in knowledge to tackle in future Mars missions. The EMM team selected instruments and a special orbit that would enable them to fill a major knowledge gap: a comprehensive picture of Mars's atmosphere.[10] Through its wide and distant route, the probe will be the first to be able to study the climate daily and through seasonal cycles, the weather events in the lower atmosphere such as dust storms, as well as the weather at different geographic areas of Mars. According to the Hope Mars Mission team, the probe will be the "first true weather satellite" at Mars.[29]

The Hope probe will study the atmospheric layers of Mars in detail and will provide data to study: the reason for a drastic climatic change in the Martian atmosphere from the time it could sustain liquid water to today, when the atmosphere is so thin water can exist only as ice or vapour, to help understand how and why Mars is losing its hydrogen and oxygen into space, and the connection between the upper and lower levels of the Martian atmosphere.[29] Data from the Hope probe will also help model Earth's atmosphere and study its evolution over millions of years.[24] All data gained from the mission will be made available to 200 universities and research institutes across the globe for the purpose of knowledge sharing.[24]

Hope spacecraft

The robotic probe is sent to Mars under the Emirates Mars Mission has been named "Hope" or Al-Amal (Arabic: مسبار الأمل), as it is intended to send out a message of optimism to millions of Arabs across the globe and encourage them towards innovation.[30] In April 2015, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid invited the Arab world to name the probe. The name was selected after thousands of suggestions were received, as it describes the core objective of the mission.[31] The name of the probe was announced in May 2015 and since then the mission is sometimes referred to as the "Hope Mars Mission".[31]

Construction and transfer to Japanese launch site

The spacecraft was assembled at LASP in Boulder, Colorado, where Emirati engineers worked and learned from their American counterparts. It launched from Tanegashima Space Center in Japan.[7] The first Mars probe of the Arab world arrived at the launch site in Japan in April 2020, after officials navigated coronavirus-related quarantine protocols and travel restrictions. However, the coronavirus forced officials to shuffle the schedule, and mission managers decided to send the probe to Japan earlier. The decision to ship the spacecraft to the launch site forced engineers in Dubai to curtail some of the planned testings on the probe, but all critical checks were completed before the orbiter left for Japan in April. The officials dispatched 11 engineers and technicians in early April to Japan, where they spent two weeks in quarantine to ensure they had no symptoms of the COVID-19 viral disease. On 20 April 2020, the Hope spacecraft left MBRSC in Dubai to begin the four-day journey to Tanegashima. Packaged inside a climate-controlled shipping container, the spacecraft was transported in a Russian-operated, Ukrainian-built Antonov An-124 cargo plane from Dubai to Nagoya, Japan. The final phase of the journey occurred aboard a ship, which carried the probe from Nagoya to Tanegashima Island on 24 April 2020. Six members of the Emirates Mars Mission team accompanied the spacecraft to Japan. Once there, they began their own two-week quarantine period as mandated by the Japanese government. When they complete the quarantine period, the personnel join the 11 engineers and technicians to complete final testing on the spacecraft inside a payload processing facility clean room at Tanegashima.[32]

Specifications

The Hope probe is built from aluminium in a honeycomb structure with a composite face-sheet. With a mass of 1,350 kilograms (2,980 lb) including the propellant, the overall size and dimensions of the probe is comparable to a small car.[33]

- Dimensions: 2.37 metres (7 ft 9 in) in width and 2.90 metres (9 ft 6 in) in length

- Mass: 1,350 kilograms (2,980 lb)

- Power: 1800 watts from two solar panels[33]

For the purpose of communication, the probe uses a high-gain antenna 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) in diameter. This antenna produces a narrow radio-wave which must point towards Earth. There are low-gain antennas in the structure of the probe for directional communication at lower bandwidth. Star trackers are used for position determination in space by studying the constellations in relation to the Sun.[33] Hope is equipped with six 120 newtons (27 lbf) thrusters and eight 5 newtons (1.1 lbf) reaction control system (RCS) thrusters. The function of the six delta-v thrusters is velocity management, while the RCS thrusters are used for attitude control and delicate maneuvering. The reaction wheels within the probe allow it to reorient itself while traveling through space, helping it point its antenna towards Earth or point any scientific instrument towards Mars.[33]

Instruments

To achieve the scientific objectives of the mission, the Hope probe is equipped with three scientific instruments:[33]

- Emirates eXploration Imager (EXI) is a multi-band camera capable of taking high resolution images with a spatial resolution of better than 8 km. It uses a selector wheel mechanism consisting of six discrete bandpass filters to sample the optical spectral region: three UV bands and three visible (RGB) bands. EXI measures properties of water, ice, dust, aerosols and abundance of ozone in Mars's atmosphere. The instrument was developed at LASP in collaboration with MBRSC.[34]

- Emirates Mars Infrared Spectrometer (EMIRS) is an interferometric thermal infrared spectrometer developed by ASU and MBRSC. It examines temperature profiles, ice, water vapour and dust in the atmosphere. EMIRS will provide a view of the lower and middle atmosphere. Development was led by ASU[33][35] with support from MBRSC.

- Emirates Mars Ultraviolet Spectrometer (EMUS) is a far-ultraviolet imaging spectrograph that measures emissions in the spectral range 100–170 nm to measure global characteristics and variability of the thermosphere, and hydrogen and oxygen coronae. Design and development was led by LASP.[36]

Launch window

The rocket was launched during a brief launch window starting on 14 July 2020.[37] The spacecraft was launched on 19 July from Tanegashima Space Center in Japan using a Mitsubishi Heavy Industries H-IIA launcher,[37] and is set to arrive at Mars in February 2021.

Guidance and navigation

KinetX Aerospace, based in Tempe, Arizona, are providing navigation services for the mission.[38] NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN) is being used to communicate with and track the spacecraft.[39] KinetX uses the radio tracking data provided by the DSN to estimate the spacecraft's trajectory and design the maneuvers necessary to keep Hope on its planned trajectory and insert into Mars orbit.[40]

Team

The mission team is divided into seven groups including Spacecraft, Logistics, Mission Operations, Project Management, Science Education and Outreach, Ground Station, and Launch Vehicle. The team is headed by Omran Sharaf, who acts as the project manager and is responsible for managing and supporting the ongoing tasks related to the Emirates Mars Mission.[41]

Sarah Amiri is the deputy project manager and the lead science investigator, who leads the team in developing the mission's objectives and aligning programmes related to instrumentation of the Hope probe.[41] The mission has been referred to as having the potential to make a lasting contribution to the economy and people of the United Arab Emirates.[42]

The mission team includes 150 Emirati engineers and 200 engineers and scientists at partner institutes in the United States, with Omran Sharaf as the project manager; Sarah Amiri, deputy project manager and the lead science investigator; Ibrahim Hamza Al Qasim, deputy project manager, strategic planning; and Zakareyya Al Shamsi, deputy project manager for the operations.[41][43]

References

- "The Journey of Emirates Mars Mission". Archived from the original on 2 November 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- "Jonathan's Space Report No. 781 Draft". 19 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Live coverage: Emirates Mars Mission launches from Japan". Spaceflight Now. 19 July 2020. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Staff (7 May 2015). "UAE Unveils Mission Plan for the First Arab Space Probe to Mars". Ministry of Cabinet Affairs. SpaceRef. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- "Emirates Mars Mission". Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre. 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Clark, Stephen (19 July 2020). "United Arab Emirates successfully sends its first mission toward Mars The spacecraft and its three scientific payloads were developed as a collaborative project between scientists at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center, the UAE Space Agency, and three universities in the United States". Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Chang, Kenneth (15 February 2020). "From Dubai to Mars, With Stops in Colorado and Japan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- "UAE positions 2020 Mars Probe as catalyst for a new generation of Arab scientists and engineers". Archived from the original on 29 June 2020.

- Al-Heeti, Abrar (4 March 2020). "Hope Mars Mission could change everything we know about the red planet". CNET. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Gibney, Elizabeth (8 July 2020). "How a small Arab nation built a Mars mission from scratch in six years". nature.com. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "Majarat Magazine". Archived from the original on 13 November 2016.

- "Emirates Mars Mission Website". Archived from the original on 29 March 2016.

- Shreck, Adam (6 May 2015). "UAE to explore Martian atmosphere with probe named 'Hope'". AP News. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Jones, Rory; Parasie, Nicolas (7 May 2015). "U.A.E. Plans to Launch Mars Probe – Scientists behind Emirati orbiter 'Hope' aim to collect data on the Red Planet". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- Berger, Brian (6 May 2015). "UAE Unveils Science Goals for 'Hope' Mars Probe". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Hope probe". Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- "Emirates Mars Mission – UAE's First Step". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016.

- Bell, Jennifer (9 April 2015). "UAE and France join hands on space". The National (Abu Dhabi). Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Staff (7 May 2015). "UAE unveils mission plan 'Hope' for first Arab space probe to Mars". Khaleej Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "Emirates Mars Mission – Mars Probe". Archived from the original on 26 September 2017.

- "Home". emiratesmarsmission.ae. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Gulf News – UAE unveils details of UAE Mars Mission". May 2015. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016.

- "The National UAE – UAE Mars Mission has a name "Hope"". May 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015.

- "UAE unveils details of UAE Mars Mission". Archived from the original on 4 April 2016.

- Gibney, Elizabeth (20 July 2020). "Arab world's first Mars probe takes to the skies". nature.com. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Sarwat Nasir (12 November 2017). "Dubai airshow unveils Hope spacecraft prototype". Khaleej Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Imogen Lillywhite (13 November 2017). "Dubai Airshow: Emirates Mars mission on track for 2020 launch". Zawya. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- Haneen Dajani (29 September 2017). "Dubai wins bid to host the 2020 International Astronautical Congress". The National. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- "EMM – Scientific Goals". Archived from the original on 6 April 2016.

- "Mashable – UAE Hope Mars Mission". Archived from the original on 5 April 2016.

- "Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum asks UAE residents to name Mars probe". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016.

- Clark, Stephen (5 May 2020). "Emirates Mars Mission arrives in Japan for launch preparations". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Emirates Mars Mission – Mars Probe Specifications". Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

- "EPSC Abstracts Vol. 12, EPSC2018-1032, 2018" (PDF). European Planetary Science Congress 2018. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2019.

- Altunaiji, Eman; Edwards, Christopher; Smith, Michael; Christensen, Philip; AlMheiri, Suhail; Reed, Heather (1 April 2017). "Emirates Mars Infrared Spectrometer (EMIRS) Overview from the Emirates Mars Mission". Egu General Assembly Conference Abstracts. 19: 15037. Bibcode:2017EGUGA..1915037A.

- Lootah, F. H.; Almatroushi, H.R.; AlMheiri, S.; Holsclaw, G.; Deighan, J.; Chaffin, M.; Reed, H.; Lillis, R. J.; Fillingim, M. O. (1 December 2017). "Emirates Mars Ultraviolet Spectrometer (EMUS) Overview from the Emirates Mars Mission". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 23: P23D–2777. Bibcode:2017AGUFM.P23D2777L.

- "Launch Schedule of the H-IIA Launch Vehicle No. 42 (H-IIA F42) which carries aboard the Hope". MHI. 18 May 2020. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "The Emirates Mars Mission Ground Segment". MBRSC. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Dunbar, Brian (20 July 2020). "Congratulations to the UAE on an Inspiring Mission of Hope". NASA Blogs, Administrator Jim Bridenstine. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Alblooshi, Mohammad (May 2020). EMIRATES MARS MISSION GROUND SEGMENT – OVERVIEW AND CURRENT STATUS (PDF). SpaceOps. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Emirates Mars Mission – Mars Team". Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Emirates Mars Mission Highlights The Power Of Hope". SpaceWatch Global. 27 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Appendix – Details of Emirates Mars Mission" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

.jpg)

.jpg)