Ekbletomys

"Ekbletomys hypenemus" is an extinct[1] oryzomyine rodent from the islands of Antigua and Barbuda, Lesser Antilles. It was described as the only species of the subgenus "Ekbletomys" of genus Oryzomys in a 1962 Ph.D. thesis, but that name is not available under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and the species remains formally unnamed. It is currently referred to as "Ekbletomys hypenemus" in the absence of a formally available name.[2] The species is now thought to be extinct, but association with introduced Rattus indicates that it survived until before 1500 BCE on Antigua.

| Ekbletomys Temporal range: Pleistocene-Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

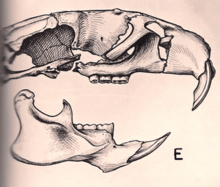

| Side view of the holotype skull | |

| Scientific classification (unresolved) | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Sigmodontinae |

| Genus: | †Ekbletomys Ray, 1962 (unavailable name) |

| Species: | †E. hypenemus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Ekbletomys hypenemus (Ray, 1962) (unavailable name) | |

.svg.png) | |

| Location of Antigua and Barbuda, where "Ekbletomys hypenemus" was endemic | |

It is known from abundant skeletal elements, which document it as the largest known oryzomyine, on par with Megalomys desmarestii, another Antillean endemic. Its morphological features indicate that it is distinct from Megalomys, which includes various other Antillean oryzomyines, and derives from a separate colonization of the Lesser Antilles by oryzomyines. In the original description, it was placed close to a species now placed in Nephelomys, but its relationships have not been studied since.

Taxonomy

Remains of "Ekbletomys" were first found on Barbuda in the summer of 1958[3] and subsequently on Antigua in 1961. In his 1962 Ph.D. thesis at Harvard University, paleontologist Clayton E. Ray described them as a new species, Oryzomys hypenemus, which he considered distinctive enough to merit its own subgenus, Ekbletomys. The specific name, hypenemus, is derived from ύπηνεμος (hypênemos), which means "leeward" in Ancient Greek and refers to the species' distribution in the Leeward Islands, and the subgeneric name, Ekbletomys, combines Ancient Greek εκβλητος (ekblêtos) "cast up" and μυς (mus) "mouse", referring to the way "Ekbletomys" probably reached its islands.[4] Because Ray's thesis does not meet the definition of a "published work" in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature,[5] both new names proposed by Ray are not available and cannot be used in formal zoological nomenclature. The name has rarely been used in the literature on Antillean oryzomyines since, and no formal description has been published; thus, the animal still lacks a formally available name.[6]

Large oryzomyines from Antigua and Barbuda have been reported in several subsequent studies, but these did not explicitly refer the material to Ray's "Oryzomys hypenemus". New material has come from Indian Creek and Burma's Quarry on Antigua and from Indiantown Trail and Sufferers on Barbuda.[7] These studies referred the Antigua and Barbuda material to "Undescribed species B", which is also known from archeological material on Guadeloupe, Montserrat and Marie-Galante. In addition to this large species, other, smaller oryzomyines may also have occurred on Antigua;[8] two species of oryzomyine were also formerly present on Barbuda.[6]

Description

"Ekbletomys" is known from numerous bones from Barbuda, including over a hundred femora and tibiofibulae (bones of the hindlimb), four substantial cranium (skull) fragments, one of which was designated by Ray as the holotype, and various others.[9] At the time of Ray's writing, the material from Antigua had not yet been completely sorted out, and consequently the description is based mainly on specimens from Barbuda.[10]

The Barbudan material, and particularly the skulls, shows a number of features distinctive enough for an oryzomyine to persuade Ray to allocate it to its own subgenus and species. The front part of the skull is short and broad. The interorbital region of the skull (located between the eyes) is narrower than that of any other oryzomyine.[10] The squamosal (back) roots of the zygomatic arches (cheekbones) are oriented perpendicular to the main axis of the skull. The incisive foramina (openings in the palate between the incisors and the molars) are extremely short. The molars are large. The palate is short, extending barely beyond the third molar. The anterocone (front cusp) of the first upper molar is divided by a marked anteromedian flexus. The length of the holotype skull is larger than that of all specimens but one of Megalomys desmarestii, indicating that "Ekbletomys" is among the largest oryzomyine species known.[11]

| Measurement | UF 2816 | UF 2815 | UF 2814 I | UF 2951 E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greatest skull length (without nasals) | 60.4 | – | – | – |

| Length of diastema[fn 2] | 18.3 | 17.3 | – | – |

| Length of incisive foramen | 6.5 | 5.9 | – | – |

| Width of palate between first molars | 6.2 | 5.5 | – | – |

| Minimum interorbital breadth | 7.1 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 8.3 |

| Crown length of upper molars | 10.3, 10.2 | 10.4, – | – | –, 10.2 |

As "Ekbletomys" and Megalomys audreyae are from the same island, a close relation between the two would be expected,[13] but the two differ so much that Ray declared any special relationship between the genus Megalomys and "Ekbletomys" to be "out of the question".[14] In all measurements that could be examined, M. audreyae, which is known only from an upper incisor and a lower jaw with the first molar missing, falls far outside the range of variation of "Ekbletomys"[15] and in addition, it differs in the shape of the folds of the molars, which are broader than in "Ekbletomys", and in the more elongate form of the lower third molar.[14]

More complete material is available for the two Megalomys species known to have survived into historic times, M. desmarestii and M. luciae. M. desmarestii is about as large as "Ekbletomys" and M. luciae is slightly smaller. In sharp contrast to the relatively narrow interorbital in "Ekbletomys", these two taxa show a very broad interorbital.[16] Also, "Ekbletomys" shows a relatively large zygomatic breadth of the skull, whereas the relative value is at the lower end of the variation among oryzomyines in Megalomys.[17] The hamular process of the squamosal bone is much longer and more slender in "Ekbletomys.[18] Megalomys also has relatively short incisive foramina, but not nearly as short as those in "Ekbletomys".[18] Although overall skull length is about equal in both species, molars of Megalomys are smaller than those of "Ekbletomys" and incisors are larger, reflecting relatively large molars and slender incisors in "Ekbletomys" and the reverse in Megalomys.[19]

Ray considered "Ekbletomys" to be most closely related to Oryzomys albigularis, a species which at the time encompassed virtually all forms now placed in the genus Nephelomys. The two agree in their robust skull with short incisive foramina, a broad braincase, a similarly formed interorbital, supraorbital crests situated close together near the middle of the skull, and presence of an anteromedian flexus on the upper first molar.[20] Ray suggested that the origin of "Ekbletomys" lies in a continental ancestor similar to Nephelomys.[21]

Distribution and habitat

"Ekbletomys hypenemus" is known from material from two small limestone caves at Two Foot Bay at the eastern side of the island of Barbuda, Antigua and Barbuda and from a site named Mill Reef in the far east of Antigua, also in Antigua and Barbuda, which has not been described in detail.[22] In both Barbuda caves, the "Ekbletomys" material was found in red to yellow unconsolidated sediments on the cave floor which were partially overlain by a darker sediment that yielded the introduced Rattus, indicating deposition after the first European contact around 1500.[23] These sediments are probably ancient owl pellets deposited by a burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia)[24] and they also yielded the frog Eleutherodactylus johnstonei; the lizards Thecadactylus rapicauda, Pholidoscelis griswoldi, and Anolis leachii; the birds Puffinus lherminieri, Zenaida aurita, Columbina passerina, Tiaris bicolor, and an unidentified fringillid; and the bats Mormoops blainvillei, Brachyphylla cavernarum, Natalus stramineus, Tadarida brasiliensis, and Molossus molossus.[25] The deposits that included "Ekbletomys" are probably very late Quaternary, but pre-Columbian, and the Antigua material ranges in age from about 2500 BCE to post-Columbian.[26]

In order to colonize Barbuda and Antigua, "Ekbletomys" must have reached the islands through overwater dispersal, probably by means of rafting.[27] Ray thought it improbable that the ancestor of the animal reached the islands through repeated overwater dispersal (island hopping) from mainland South America along the Lesser Antilles all the way to Barbuda. Even when sea levels dropped during the Pleistocene, the animal would still have been required to overcome seven water barriers, a series of voyages "no less wondrous than those of Sindbad."[28] Instead, he argued that the animal reached the islands directly on a raft from mainland South America, probably from one of the continent's large rivers.[29]

Footnotes

- All measurements are in millimeters. Where two measurements are given, the first refers to the left and the second to the right side of the skull.

- The toothless space between the incisors and the molars.

References

- Ray, 1962, table 10

- Turvey, 2009, unnumbered table

- Auffenberg, 1958, p. 248

- Ray, 1962

- International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, 1999, Art. 8. http://www.iczn.org/iczn/index.jsp Archived 2009-05-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Turvey, 2009, unnumbered table, note 20

- Steadman et al., 1984; Watters et al., 1984; Pregill et al., 1988, 1994

- Pregill et al., 1988, p. 22

- Ray, 1962, pp. 112–115

- Ray, 1962, p. 107

- Ray, 1962, pp. 107, 116–117

- Ray, 1962, table 11

- Ray, 1962, p. 164

- Ray, 1962, p. 165

- Ray, 1962, table 33

- Ray, 1962, p. 120

- Ray, 1962, p. 121

- Ray, 1962, p. 124

- Ray, 1962, p. 127

- Ray, 1962, pp. 165–166

- Ray, 1962, p. 167

- Ray, 1962, p. 109; Pregill et al., 1994, pp. 16–17

- Ray, 1962, pp. 109–110

- Ray, 1962, p. 110

- Ray, 1962, table 10; Frost, 2009, Uetz et al., 2009, Peterson, 1992, Simmons, 2005, for nomenclature

- Ray, 1962, p. 112

- Ray, 1962, pp. 176–185

- Ray, 1962, p. 188

- Ray, 1962, p. 189

Literature cited

- Auffenberg, W. 1958. A small fossil herpetofauna from Barbuda, Leeward Islands, with the description of a new species of Hyla. Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 21(3):248–254.

- Frost, D.R. 2009. Amphibian Species of the World: an online reference. Version 5.3 (12 February 2009). Available at http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/. American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA.

- Peterson, A.P. 2002. Zoonomen Nomenclatural data. Available at http://www.zoonomen.net. Accessed September 11, 2009.

- Pregill, G.K., Steadman, D.W., Olson, S.L. and Grady, F.V. 1988. Late Holocene fossil vertebrates from Burma Quarry, Antigua, Lesser Antilles. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 463:1–27.

- Pregill, G.K., Steadman, D.W. and Watters, D.R. 1994. Late Quaternary vertebrate faunas of the Lesser Antilles: historical components of Caribbean biogeography. Bulletin of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History 30:1–51.

- Ray, C. E. 1962. The Oryzomyine Rodents of the Antillean Subregion. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Harvard University, 211 pp.

- Simmons, N.B. 2005. Order Chiroptera. Pp. 312–529 in Wilson, D.E. and Reeder, D.M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference. 3rd ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols., 2142 pp. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0

- Steadman, D.W., Pregill, G.K. and Olson, S.L. 1984. Fossil vertebrates from Antigua, Lesser Antilles: Evidence for late Holocene human-caused extinctions in the West Indies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 81:4448–4451.

- Turvey, S.T. 2009. Holocene Extinctions. Oxford University Press US, 359 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-953509-5

- Uetz, P., et al. 2009. The Reptile Database. Available at http://www.reptile-database.org. Accessed September 11, 2009.

- Watters, D.R., Reitz, E.J., Steadman, D.W. and Pregill, G.K. 1984. Vertebrates from archaeological sites on Barbuda, West Indies. Annals of Carnegie Museum 53(13):383–412.

- Wing, E.S., Hoffman, C.A., Jr. and Ray, C.E. 1968. Vertebrate remains from Indian sites on Antigua, West Indies. Caribbean Journal of Science 8(3–4):123–139.