Transandinomys talamancae

Transandinomys talamancae is a rodent in the genus Transandinomys that occurs from Costa Rica to southwestern Ecuador and northern Venezuela. Its habitat consists of lowland forests up to 1,500 m (5,000 ft) above sea level. With a body mass of 38 to 74 g (1.3 to 2.6 oz), it is a medium-sized rice rat. The fur is soft and is reddish to brownish on the upperparts and white to buff on the underparts. The tail is dark brown above and lighter below and the ears and feet are long. The vibrissae (whiskers) are very long. In the skull, the rostrum (front part) is long and the braincase is low. The number of chromosomes varies from 34 to 54.

| Transandinomys talamancae | |

|---|---|

| |

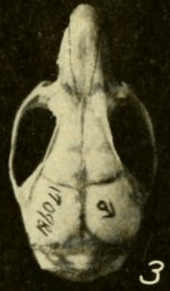

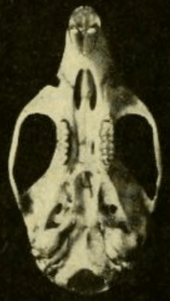

| Skull of a male from Gatun, Panama, seen from above[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Cricetidae |

| Subfamily: | Sigmodontinae |

| Genus: | Transandinomys |

| Species: | T. talamancae |

| Binomial name | |

| Transandinomys talamancae (J.A. Allen, 1891) | |

| |

| Distribution of Transandinomys talamancae in southern Central America and northwestern South America[3] | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

The species was first described in 1891 by Joel Asaph Allen and thereafter a variety of names, now considered synonyms, were applied to local populations. It was lumped into a widespread species "Oryzomys capito" (now Hylaeamys megacephalus) from the 1960s until the 1980s and the current allocation of synonyms dates from 1998. It was placed in the genus Oryzomys until 2006, as Oryzomys talamancae, but is not closely related to the type species of that genus and was therefore moved to a separate genus Transandinomys in 2006. It shares this genus with Transandinomys bolivaris, which has even longer vibrissae; the two overlap broadly in distribution and are morphologically similar.

Active during the night, Transandinomys talamancae lives on the ground and eats plants and insects. Males move more and have larger home ranges than most females. It breeds throughout the year, although few individuals survive for more than a year. After a gestation period of about 28 days, two to five young are born, which reach sexual maturity within two months. A variety of parasites occur on this species. Widespread and common, it is of no conservation concern.

Taxonomy

In 1891, Joel Asaph Allen was the first to scientifically describe Transandinomys talamancae, when he named Oryzomys talamancae from a specimen from Talamanca, Costa Rica. He placed it in the genus Oryzomys, then more broadly defined than it is now, and compared it to both the marsh rice rat (O. palustris) and to O. laticeps.[14] Several other names that are now recognized as synonyms of Transandinomys talamancae were introduced in the following years. In 1899, Allen described Oryzomys mollipilosus, O. magdalenae, and O. villosus from Magdalena Department, Colombia.[15] Oldfield Thomas added O. sylvaticus from Santa Rosa, Ecuador in 1900[16] and O. panamensis from Panama City, Panama, in 1901.[17] In the same year, Wirt Robinson and Markus Lyon named Oryzomys medius from near La Guaira, Venezuela.[18] Allen added O. carrikeri from Talamanca, Costa Rica, in 1908.[19]

Edward Alphonso Goldman revised North American Oryzomys in 1918. He placed both panamensis and carrikeri as synonyms of Oryzomys talamancae and mentioned O. mollipilosus and O. medius as closely related species. O. talamancae was the only member of its own species group, which Goldman regarded as closest to Oryzomys bombycinus (=Transandinomys bolivaris).[20] In 1960, Philip Hershkovitz listed talamancae, medius, magdalenae, sylvaticus, and mollipilosus among the many synonyms of "Oryzomys laticeps", a name later replaced by "Oryzomys capito".[21] The species remained lumped under Oryzomys capito until 1983, when Alfred Gardner again listed it as a valid species, an action more fully documented by Guy Musser and Marina Williams in 1985.[22] Musser and Williams also found that the holotype of Oryzomys villosus, the affinities of which had been disputed, in fact consisted of a skin of O. talamancae and a skull of the Oryzomys albigularis group (equivalent to the current genus Nephelomys). They restricted the name to the skin, making villosus a synonym of O. talamancae.[23] They also examined the holotypes of panamensis, carrikeri, mollipilosus, medius, and magdalenae and identified them as examples of Oryzomys talamancae. Additionally, they included sylvaticus and Oryzomys castaneus J.A. Allen, 1901, from Ecuador as synonyms, but without examining the holotypes.[24] Musser and colleagues reviewed the group again in 1998 and confirmed that sylvaticus represents Oryzomys talamancae; however, they found that castaneus was in fact an example of Oryzomys bolivaris (the current Transandinomys bolivaris).[25]

In 2006, Marcelo Weksler published a phylogenetic analysis of Oryzomyini ("rice rats"), the tribe to which Oryzomys is allocated, using morphological data and DNA sequences from the IRBP gene. His results showed species of Oryzomys dispersed across Oryzomyini and suggested that most species in the genus should be allocated to new genera.[26] Oryzomys talamancae was also included; it appeared within "clade B", together with other species formerly associated with Oryzomys capito. Some analyses placed it closest to species now placed in Euryoryzomys or Nephelomys, but with low support.[27] Later in the same year, he, together with Alexandre Percequillo and Robert Voss, named ten new genera for species previously placed in Oryzomys, including Transandinomys, which has Oryzomys talamancae (now Transandinomys talamancae) as its type species.[13] They also included Oryzomys bolivaris, which was not included in Weksler's phylogenetic study, in this new genus. The two species are morphologically similar, but Weksler and colleagues could identify only one synapomorphy (shared-derived trait) for them: very long superciliary vibrissae (vibrissae, or whiskers, above the eyes).[28] Transandinomys is one of about 30 genera in Oryzomyini, a diverse assemblage of American rodents of over a hundred species,[29] and on higher taxonomic levels in the subfamily Sigmodontinae of family Cricetidae, along with hundreds of other species of mainly small rodents.[30]

Several common names have been proposed for Transandinomys talamancae, including "Talamanca Rice Rat",[31] "Transandean Oryzomys",[32] and "Talamancan Rice Rat".[2]

Description

Transandinomys talamancae is a medium-sized, brightly colored rice rat.[33] It is similar to T. bolivaris and the two are often confused.[34] They are about as large, but in T. talamancae the tail is longer and the hindfeet shorter.[35] Both species share uniquely long vibrissae, with both the mystacial (above the mouth) and superciliary vibrissae extending to or beyond the back margin of the ears when laid back against the head, but those in T. bolivaris are substantially longer.[13] H. alfaroi, a widespread species ranging from Mexico to Ecuador, is also similar.[36] It is smaller and darker, but young adult T. talamancae are similar in color to adult H. alfaroi and often misidentified.[37] Hylaeamys megacephalus,[Note 1] with which T. talamancae was synonymized for some decades, is similar in body size, but is not known to overlap with T. talamancae in range.[39]

The fur is short, dense and soft in Transandinomys talamancae;[40] in T. bolivaris, it is longer and even more soft and dense.[41] The color of the upperparts varies from reddish to brownish, becoming lighter towards the sides and the cheeks.[31] The underparts are white to buff, with the bases of the hairs plumbeous (lead-colored).[31] The fur of T. bolivaris is darker: dark brown above and dark gray below.[42] H. megacephalus also has darker fur.[43] Juveniles have thin, gray fur, which is molted into the dark brown subadult fur when the animal is about 35 to 40 days old. This fur is replaced by the bright adult fur at age 49 to 56 days.[44] Juveniles are never blackish as in T. bolivaris.[42] The ears are dark brown,[40] large, and densely covered with very small hairs.[45]

| Country | n[Note 2] | Head and body | Tail | Hindfoot | Ear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panama | 22 | 124.4 (101–136) | 124.7 (110–143) | 29.2 (27–32) | 21.1 (16–25) |

| Colombia | 13 | 135.2 (120–151) | 125.2 (114–140) | 29.5 (27–32) | 19.0 (18–22) |

| Ecuador | 20[Note 3] | 124 (118–136) | 128.5 (118–137) | 29.1 (28–31) | – |

| Measurements are in millimeters and in the form "average (minimum–maximum)". | |||||

The sparsely haired tail is approximately as long as the head and body.[45] It is dark brown above and lighter below.[40] In contrast, the tail of H. megacephalus has little to no difference in color between the upper and lower surface.[43] In 2006, Weksler and colleagues noted tail coloration as a difference between the two species of Transandinomys (bicolored in T. talamancae and unicolored in T. bolivaris),[13] but in their 1998 study, Musser and colleagues could not find differences in tail coloration between their Panamanian samples of the two species.[47]

The hindfeet are long and have the three central digits longer than the two outer ones.[47] They are white to pale yellow above,[40] where the foot is covered with hairs, which are longer than in T. bolivaris.[48] The digits of the hindfeet are surrounded by ungual tufts of silvery hair that are longer than the claws themselves.[49] The claws are short and sharp.[50] Parts of the sole are covered by indistinct scales (squamae), which are usually entirely absent in T. bolivaris.[51] The pads are moderately large.[47]

The length of the head and body is 105 to 151 mm (4.1 to 5.9 in), tail length 105 to 152 mm (4.1 to 6.0 in), hindfoot length 26 to 32 mm (1.0 to 1.3 in), ear length 17 to 24 mm (0.67 to 0.94 in), and body mass 38 to 74 g (1.3 to 2.6 oz).[52] As in most oryzomyines, females have eight mammae.[53] There are 12 thoracic vertebra with associated ribs, 7 lumbars, and 29 caudals; a pair of supernumerary (additional) ribs is occasionally present.[54]

Skull and teeth

The skull has a long rostrum (front part), a broad interorbital region (between the eyes), and a low braincase.[55] It differs from that of T. bolivaris in various proportions, which are more apparent in adults than in juveniles;[48] the skull of H. megacephalus is distinctly larger.[43] The zygomatic plate is broad and includes a well-developed zygomatic notch at its front. Its back margin is level with the front of the first upper molar.[56] The zygomatic arch (cheekbone) is heavy. The nasal and premaxillary bones extend about as far backward.[31] The interorbital region is narrowest toward the front and shows weak beading at its margins;[57] T. bolivaris is similar, but has stronger beading[58] and H. megacephalus entirely lacks the beading.[59] The parietal bone is usually limited to the roof of the braincase and does not extend to its side, as it does in most T. bolivaris.[58] The interparietal bone, part of the roof of the braincase, is large.[31]

The incisive foramina (openings in the front part of the palate) are short and do not reach between the first molars;[40] they are longer in H. alfaroi.[37] The bony palate is long and extends beyond the end of the molar row and the back margin of the maxillary bones.[60] The posterolateral palatal pits, which perforate the palate near the third molars, are small, and may or may not be recessed into a fossa.[61] The sphenopalatine vacuities (openings in the roof of the mesopterygoid fossa, behind the palate) are also small,[31] as are the auditory bullae.[40] As in most oryzomyines, the subsquamosal fenestra, an opening at the back of the skull, is present.[62] The pattern of grooves and foramina (openings) in the skull indicates that the circulation of the arteries of the head in T. talamancae follows the primitive pattern, as in most similar species but unlike in Hylaeamys.[59]

The mandible (lower jaw) is less robust than in T. bolivaris.[63] The coronoid process (a process in the back part of the bone) is small and the capsular process, which houses the root of the lower incisor, are small.[31] The mental foramen, located in the diastema between the lower incisor and the first molar, opens towards the side, as usual in oryzomyines.[64] The upper and lower masseteric ridges, which anchor some of the chewing muscles, do not join into a single crest and extend forward to below the first molar.[65]

The upper incisor is opisthodont, with the cutting edge oriented backward.[66] As usual in oryzomyines, the molars are brachydont (low-crowned) and bunodont (with the cusps higher than the connecting crests).[67] The first upper molar is narrower than in T. bolivaris. In this species, but unlike in many other rice rats, including H. alfaroi and E. nitidus, the mesoflexus on the second upper molar, which separates the paracone (one of the main cusps) from the mesoloph (an accessory crest), is not divided in two by an enamel bridge.[63] The hypoflexid on the second lower molar, the main valley between the cusps, is very long, extending more than halfway across the tooth; in this trait, the species is again similar to T. bolivaris but unlike H. alfaroi.[68] Each of the upper molars has three roots (two at the labial, or outer, side and one at the lingual, or inner, side) and each of the lower molars has two (one at the front and one at the back); T. talamancae lacks the additional small roots that are present in various other oryzomyines, including species of Euryoryzomys, Nephelomys, and Handleyomys.[69]

Male reproductive anatomy

As is characteristic of Sigmodontinae, Transandinomys talamancae has a complex penis, with the distal (far) end of the baculum (penis bone) ending in a structure consisting of three digits.[71] As in most oryzomyines, the central digit is larger than the two at the sides.[72] The outer surface of the penis is mostly covered by small spines, but there is a broad band of nonspinous tissue.[73]

Some features of the accessory glands in the male genital region vary among oryzomyines. In Transandinomys talamancae,[Note 4] a single pair of preputial glands is present at the penis. As is usual for sigmodontines, there are two pairs of ventral prostate glands and a single pair of anterior and dorsal prostate glands. Part of the end of the vesicular gland is irregularly folded, not smooth as in most oryzomyines.[75]

Karyotype

The karyotype in T. talamancae is variable. Samples from two different localities in Venezuela have 34 chromosomes and a fundamental number of 64 chromosomal arms (2n = 34, FN = 64).[77] Four specimens from another Venezuelan locality each have a different karyotype, with the number of chromosomes ranging from 40 to 42 and the fundamental number from 66 to perhaps 67.[Note 5] The autosomes (non-sex chromosomes) of the 2n = 34 karyotype all have two major arms, but the 2n = 40–42 karyotypes include several acrocentric autosomes, which only have one major arm. The 2n = 34 karyotype includes two large submetacentric pairs, which have two long arms but one distinctly longer than the other, and one pair of subtelocentric chromosomes, with a long and a much shorter arm, but the 2n = 40–42 karyotypes lack the submetacentrics and have another pair of subtelocentrics.[79] Both Robertsonian translocations (fusions of the long arm of one chromosome with the long arm of another and the short arm of the one with the short arm of the other) and pericentric inversions (reversals of part of a chromosome that includes the centromere) are needed to explain the difference between the two groups. Musser and colleagues, in discussing these karyotypes, assumed that the 2n = 40–42 sample was from within a hybrid zone between two karyotypic morphs.[80]

The karyotype of an Ecuadorean sample from north of the Gulf of Guayaquil is similar to that of Venezuelan animals at 2n = 36, FN = 60; it includes four acrocentric and two subtelocentric pairs and no submetacentrics. In contrast, a sample from south of the Gulf had 2n = 54, FN = 60, including 23 pairs of acrocentrics and four pairs of metacentrics (with two equally long arms). Musser and colleagues termed the difference between the two Ecuadorian forms "impressive"[80] and noted that further research was needed to understand the karyotypic differentiation within the species more fully.[81] Both T. bolivaris and H. alfaroi have more chromosomes and arms, at 2n = 58, FN = 80 and 2n = 60–62, FN = 100–104 respectively.[82] Hylaeamys megacephalus has 2n = 54, FN = 58–62 and the similar Hylaeamys perenensis has 2n = 52, FN = 62; these karyotypes resemble that of southern Ecuadorean T. talamancae.[83]

Distribution and habitat

The distribution of Transandinomys talamancae extends from northwestern Costa Rica south and east to northern Venezuela and southwestern Ecuador, up to 1,500 m (5,000 ft) above sea level.[32] It is a forest species and occurs in both evergreen and deciduous forest.[84] Although its distribution broadly overlaps that of T. bolivaris, it is more widely distributed in South America because of its greater tolerance of dry forest habitats.[85]

Transandinomys talamancae reaches the northern limit of its range in Costa Rica, but except for one record from the far northwest (in Guanacaste Province near the southern margin of Lake Nicaragua), it is known only from the southeastern third of the country. In contrast, T. bolivaris and H. alfaroi occur further north, into Honduras and Mexico respectively. It occurs throughout Panama at low elevations. Along the Pacific coast in Colombia and Ecuador, it is found on the coastal plain and the adjacent foothills of the Andes.[85] The southernmost known record is in far southwestern Ecuador, but the species may range into nearby Peru.[84]

It also occurs throughout northern Colombia at low elevations and into western Venezuela west of Lake Maracaibo and at the foot of the western part of the Venezuelan Coastal Range east to Guatopo National Park.[85] Hylaeamys megacephalus occurs further to the east in the eastern portion of the coastal range, separated by the coastal Eastern Caribbean Dry Zone.[43] There is a record from the Orinoco Delta of northeastern Venezuela, well within the range of Hylaeamys megacephalus, but Musser and colleagues suggest that this is based on mislabeled specimens.[86] The species has also been found on the narrow strip between the Llanos and the Andes (Cordillera Oriental and Cordillera de Mérida) in eastern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela.[85] The unforested Llanos separate these areas from Hylaeamys populations. Hylaeamys perenensis[Note 6] does, however, occur further south along the eastern foothills of the Cordillera Oriental in Colombia and it is possible that the two overlap in this area.[43]

Ecology and behavior

Transandinomys talamancae is a common, even abundant, species.[88] Its ecology was studied by Theodore Fleming in the Panama Canal Zone.[89] It lives on the ground and is active during the night.[90] The animal nests above ground level and occasionally enters burrows also used by the pocket mouse Liomys adspersus.[91] Its diet is omnivorous: including both plant material such as seeds and fruits; and adult and larval insects.[44]

Males tend to travel longer distances than females. The average home range size in Fleming's study was 1.33 hectares (3.3 acres); males had larger home ranges on average.[92] Specimens that were once captured tended to be captured more frequently than those that had never been captured.[93] Fleming estimated that population densities reached peaks of up to 4.3 per ha (1.7 per acre) late in the rainy season (October–November), but dropped to near zero around June; however, these figures may well be underestimates.[94] In central Venezuela, population densities vary from 5.5 to 9.6 per ha (2.2 to 3.8 per acre).[95]

In Panama, this species breeds year-round without apparent seasonal variability.[96] According to Omar Linares's Mamíferos de Venezuela (Mammals of Venezuela), reproductive activity is highest in June–July and December.[95] In the laboratory, the gestation period is 28 days;[97] Linares reports 20 to 30 days in the wild.[95] Females produce an average of six litters per year and there are two to five (average 3.92) young per litter, so that a single female may produce about 24 young per year;[98] this is likely an overestimate because most females would not live for a full year. Larger females may have larger litters.[99] Animals become sexually mature when less than two months old; in Fleming's study, some females in juvenile fur, probably less than 50 days old, were already pregnant.[100] The oldest specimen Fleming observed was nine months old;[101] he estimated that animals were unlikely to live for more than a year in the wild[102] and that the mean age at death was 2.9 months.[103]

Ten species of mites (Gigantolaelaps aitkeni,[104][Note 7] Gigantolaelaps gilmorei, Gigantolaelaps oudemansi, Gigantolaelaps wolffsohni, Haemolaelaps glasgowi, Laelaps dearmasi, Laelaps pilifer, Laelaps thori, Mysolaelaps parvispinosus,[110] and Paraspeleognathopsis cricetidarum),[111] thirteen chiggers (Aitkenius cunctatus,[112] Ascoschoengastia dyscrita, Eutrombicula alfreddugesi, Eutrombicula goeldii, Intercutestrix tryssa, Leptotrombidium panamensis, Myxacarus oscillatus, Pseudoschoengastia abditiva, Pseudoschoengastia bulbifera, Trombicula dunni, and Trombicula keenani),[113] and four fleas (Jellisonia sp., Polygenis roberti, Polygenis klagesi, and Polygenis dunni) have been found on T. talamancae in Panama.[114] G. aitkeni has also been found on this species in Colombia.[105] In addition, the sucking lice Hoplopleura nesoryzomydis and Hoplopleura oryzomydis occur on T. talamancae.[115]

Conservation status

A widespread and common species, Transandinomys talamancae is listed as "Least Concern" by the IUCN Red List. It occurs in numerous protected areas, tolerates disturbed habitats well, and no important threats are known.[2]

Notes

- Oryzomys megacephalus, as used by Musser et al. (1998), was more broadly defined than the current Hylaeamys megacephalus (it was transferred to the new genus Hylaeamys by Weksler and colleagues in the same 2006 paper that introduced Transandinomys); in their definition, it occurred throughout Amazonia and north to Trinidad and south to Paraguay.[37] However, western Amazonian populations of the species have since been separated into a different species, Hylaeamys perenensis. In the following comparisons, based on Musser et al. (1998) who did not separate the two, only H. megacephalus is mentioned, but both species are morphologically virtually identical and are known to differ only in size, karyotype, and mitochondrial DNA sequences.[38]

- Number of specimens measured.

- 19 for tail length.

- The male accessory glands of T. talamancae, and of a number of other sigmodontines, were described by Voss and Linzey (1981). Their sample of "Oryzomys capito" included specimens from Panama and Trinidad, representing Transandinomys talamancae and Hylaeamys megacephalus, respectively, but their description can be applied to both.[74]

- In one specimen, it could not be determined whether FN was 66 or 67; the other three had 66.[78]

- Reported as Oryzomys megacephalus by Musser et al. (1998), but only perenensis is currently recorded from Colombia.[87]

- This species was described among others from specimens of "Oryzomys laticeps" from Rio Cobaría, Arauca Department[105] (actually in Boyacá Department);[106] San Juan Nepomuceno, Bolívar Department;[105] Socorre, upper Rio Sinu, Bolívar, Colombia;[107] and Cerro Azul, Panama.[104] "Oryzomys laticeps", as defined in the 1960s, included Transandinomys talamancae and no other species that occur in this region;[108] furthermore, Musser et al. (1998) listed Oryzomys talamancae for all these localities.[109]

References

- Goldman, 1918, plate IV

- Anderson et al., 2017

- Musser et al., 1998, fig. 66; Linares, 1998, map 134

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 273–274

- Allen, 1891, p. 193

- Allen, 1899, p. 208

- Allen, 1899, p. 209

- Allen, 1899, p. 210

- Thomas, 1900, p. 272

- Thomas, 1901, p. 252

- Robinson and Lyon, 1901, p. 142

- Allen, 1908, p. 656

- Weksler et al., 2006, p. 25

- Allen, 1891, pp. 193–194

- Allen, 1899, pp. 208–210; Musser et al., 1998, pp. 273–274

- Thomas, 1900, pp. 272–273

- Thomas, 1901, pp. 252–253

- Robinson and Lyon, 1901, pp. 142–143

- Allen, 1908, pp. 656–657

- Goldman, 1918, pp. 71–74

- Hershkovitz, 1960, p. 544; Musser et al., 1998, p. 179

- Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 9

- Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 7

- Musser and Williams, 1985, pp. 13–14

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 275–276

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 75–77

- Weksler, 2006, figs. 34–39

- Weksler et al., 2006, p. 26

- Weksler, 2006, p. 3

- Musser and Carleton, 2005

- Goldman, 1918, p. 73

- Musser and Carleton, 2005, p. 1155

- Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 14; Musser et al., 1998, p. 173

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 125

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 127

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 167, 169

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 169

- Patton et al., 2000, p. 140

- Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 18; Musser et al., 1998, p. 169

- Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 14

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 127–128

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 128–129

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 173

- Fleming, 1970, p. 479

- Goldman, 1918, p. 71

- Musser and Williams, 1985, table 2

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 129

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 131

- Goldman, 1918, pp. 71–72

- Goldman, 1918, p. 72

- Weksler et al., 2006, p. 25; Musser et al., 1998, p. 124

- Linares, 1998, p. 287; Tirira, 2007, p. 200; Reid, 2009, p. 208

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 17, 19

- Steppan, 1995, table 5

- Goldman, 1918, p. 73; Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 14

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 31–32

- Weksler, 2006, p. 29, table 5

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 135

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 174

- Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 14; Weksler, 2006, pp. 34–35

- Goldman, 1918, p. 73; Weksler, 2006, p. 35; Musser and Williams, 1985, p. 14

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 38–39

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 140

- Weksler, 2006, p. 41

- Weksler, 2006, p. 42

- Weksler, 2006, p. 43

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 43–44

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 140–141

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 42–43

- Goldman, 1918, plate V

- Weksler, 2006, p. 55

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 55–56

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 56–57

- Weksler, 2006, p. 58, footnote 10

- Weksler, 2006, pp. 57–58; Voss and Linzey, 1981, p. 13

- Goldman, 1918, plate VI

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 163

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 163–164

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 164–165

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 165

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 165–166

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 125, 169, table 13

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 174; Patton et al., 2000, p. 140

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 158

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 157

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 157–158, footnote 9

- Musser and Carleton, 2005, pp. 1151, 1153

- Reid, 2009, p. 208; Tirira, 2007, p. 200

- Fleming, 1970; 1971

- Fleming, 1971, p. 5

- Fleming, 1971, p. 60

- Fleming, 1971, p. 50

- Fleming, 1971, p. 22

- Fleming, 1971, p. 23, fig. 6

- Linares, 1998, p. 288

- Fleming, 1971, p. 40

- Fleming, 1971, p. 65

- Fleming, 1971, table 11

- Fleming, 1971, p. 41

- Fleming, 1971, p. 43

- Fleming, 1971, p. 29

- Fleming, 1971, p. 32

- Fleming, 1971, p. 48

- Lee and Strandtmann, 1967, p. 30

- Lee and Strandtmann, 1967, p. 28

- Musser et al., 1998, p. 259

- Lee and Strandtmann, 1967, p. 29

- Hershkovitz, 1960, p. 544; see Musser et al. (1998) for review.

- Musser et al., 1998, pp. 150 (locality 16), 151 (localities 52, 53), 153 (locality 68)

- Tipton et al., 1966, p. 42

- Clark, 1967

- Brennan and Reed, 1979, p. 535

- Brennan and Yunker, 1966, p. 262

- Tipton and Méndez, 1966, p. 330

- Durden and Musser, 1994, p. 30

Literature cited

- Allen, J.A. 1891. Descriptions of two supposed new species of mice from Costa Rica and Mexico, with remarks on Hesperomys melanophrys of Coues. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 14(850):193–196.

- Allen, J.A. 1899. New rodents from Colombia and Venezuela. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 12:195–218.

- Allen, J.A. 1908. Mammals from Nicaragua. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 24:647–670.

- Anderson, R.P.; Aguilera, M.; Gómez-Laverde, M.; Samudio, R.S. Jr.; Pino, J.L. (2017). "Transandinomys talamancae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15615A22332803. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- Brennan, J.M. and Reed, J.T. 1973. The Neotropical genus Aitkenius: Three New species and other records from Venezuela (Acarina: Trombiculidae) (subscription required). The Journal of Parasitology 59(3):531–535.

- Brennan, J.M. and Yunker, C.E. 1966. The chiggers of Panama (Acarina: Trombiculidae). pp. 221–266 in Wenzel, R.L. and Tipton, V.J. (eds.). Ectoparasites of Panama. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

- Clark, G.M. 1967. New Speleognathinae from Central and South American mammals (Acarina: Trombidiformes). Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 34:240–243.

- Durden, L.A. and Musser, G.G. 1994. The sucking lice (Insecta, Anoplura) of the world: a taxonomic checklist with records of mammalian hosts and geographical distributions. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 218:1–90.

- Fleming, T.H. 1970. Notes on the rodent faunas of two Panamanian forests (subscription required). Journal of Mammalogy 51(3):473–490.

- Fleming, T.H. 1971. Population ecology of three species of Neotropical rodents. Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 143:1–77.

- Goldman, E.A. 1918. The rice rats of North America. North American Fauna 43:1–100.

- Handley, C.O., Jr. 1966. Checklist of the mammals of Panama. pp. 753–795 in Wenzel, R.L. and Tipton, V.J. (eds.). Ectoparasites of Panama. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, xii + 861 pp.

- Hershkovitz, P.M. 1960. Mammals of northern Colombia, preliminary report no. 8: Arboreal rice rats, a systematic revision of the subgenus Oecomys, genus Oryzomys. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 110:513–568.

- Lee, D. and Strandtmann, R.W. 1967. Two new species of Gigantolaelaps (Acarina: Laelaptidae) with a key to the females (subscription required). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 40(1):25–32.

- Linares, O.J. 1998. Mamíferos de Venezuela. Caracas: Sociedad Conservacionista Audubon de Venezuela and British Petroleum, 691 pp. (in Spanish). ISBN 980-6326-16-4

- Musser, G.G.; Carleton, M.D. (2005). "Superfamily Muroidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 1155. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Musser, G.G. and Williams, M.M. 1985. Systematic studies of oryzomyine rodents (Muridae): Definitions of Oryzomys villosus and Oryzomys talamancae. American Museum Novitates 2810:1–22.

- Musser, G.G., Carleton, M.D., Brothers, E.M. and Gardner, A.L. 1998. Systematic studies of oryzomyine rodents (Muridae: Sigmodontinae): diagnoses and distributions of species formerly assigned to Oryzomys "capito". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 236:1–376.

- Patton, J.L., da Silva, M.N.F. and Malcolm, J.R. 2000. Mammals of the Rio Juruá and the evolutionary and ecological diversification of Amazonia. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 244:1–306.

- Reid, F. 2009. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press US, 346 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-534322-9

- Robinson, W. and Lyon, M.W., Jr. 1901. An annotated list of mammals collected in the vicinity of La Guaira, Venezuela. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 24(1246):135–162.

- Thomas, O. 1900. Descriptions of new Neotropical mammals. Annals and Magazine of Natural History (7)5:269–274.

- Thomas, O. 1901. New Neotropical mammals, with a note on the species of Reithrodon. Annals and Magazine of Natural History (7)8:246–255.

- Tipton, V.J. and Méndez, E. 1966. The fleas (Siphonaptera) of Panama. pp. 289–385 in Wenzel, R.L. and Tipton, V.J. (eds.). Ectoparasites of Panama. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

- Tipton, V.J., Altman, R.M. and Keenan, C.M. 1966. Mites of the subfamily Laelaptinae in Panama (Acarina: Laelaptidae). pp. 23–82 in Wenzel, R.L. and Tipton, V.J. (eds.). Ectoparasites of Panama. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

- Tirira, D. 2007. Guia de campo de los mamíferos del Ecuador. Quito: Ediciones Murciélago Blanco, publicación especial sobre los mamíferos del Ecuador 6, 576 pp. (in Spanish). ISBN 9978-44-651-6

- Weksler, M. 2006. Phylogenetic relationships of oryzomyine rodents (Muroidea: Sigmodontinae): separate and combined analyses of morphological and molecular data. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 296:1–149.

- Weksler, M., Percequillo, A.R. and Voss, R.S. 2006. Ten new genera of oryzomyine rodents (Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae). American Museum Novitates 3537:1–29.

External links