Edward Weston

Edward Henry Weston (March 24, 1886 – January 1, 1958) was a 20th-century American photographer. He has been called "one of the most innovative and influential American photographers..."[1] and "one of the masters of 20th century photography."[2] Over the course of his 40-year career Weston photographed an increasingly expansive set of subjects, including landscapes, still lives, nudes, portraits, genre scenes and even whimsical parodies. It is said that he developed a "quintessentially American, and especially Californian, approach to modern photography"[3] because of his focus on the people and places of the American West. In 1937 Weston was the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship, and over the next two years he produced nearly 1,400 negatives using his 8 × 10 view camera. Some of his most famous photographs were taken of the trees and rocks at Point Lobos, California, near where he lived for many years.

Edward Weston | |

|---|---|

Weston c. 1915 | |

| Born | Edward Henry Weston March 24, 1886 |

| Died | January 1, 1958 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Photography |

Notable work | Nude, 1925 (1925), Pepper No. 30 (1930), Nude (Charis, Santa Monica) (1936) |

Weston was born in Chicago and moved to California when he was 21. He knew he wanted to be a photographer from an early age, and initially his work was typical of the soft focus pictorialism that was popular at the time. Within a few years, however, he abandoned that style and went on to be one of the foremost champions of highly detailed photographic images.

In 1947 he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and he stopped photographing soon thereafter. He spent the remaining ten years of his life overseeing the printing of more than 1,000 of his most famous images.

Life and work

1886–1906: Early life

Weston was born in Highland Park, Illinois, the second child and only son of Edward Burbank Weston, an obstetrician, and Alice Jeanette Brett, a Shakespearean actress. His mother died when he was five years old and he was raised mostly by his sister Mary, whom he called "May" or "Maisie". She was nine years older than he, and they developed a very close bond that was one of the few steady relationships in Weston's life.[4]

His father remarried when he was nine, but neither Weston nor his sister got along with their new stepmother and stepbrother. After May was married and left their home in 1897, Weston's father devoted most of his time to his new wife and her son. Weston was left on his own much of the time; he stopped going to school and withdrew into his own room in their large home.[4]

As a present for his 16th birthday Weston's father gave him his first camera, a Kodak Bull's-Eye No. 2, which was a simple box camera. He took it on vacation in the Midwest, and by the time he returned home his interest in photography was enough to lead him to purchase a used 5 × 7 inch view camera. He began photographing in Chicago parks and a farm owned by his aunt, and developed his own film and prints. Later he would remember that even at that early age his work showed strong artistic merit. He said, "I feel that my earliest work of 1903 ‒ though immature ‒ is related more closely, both with technique and composition, to my latest work than are several of my photographs dating from 1913 to 1920, a period in which I was trying to be artistic."[5]

In 1904 May and her family moved to California, leaving Weston further isolated in Chicago. He earned a living by taking a job at a local department store, but he continued to spend most of his free time taking photos, Within two years he felt confident enough of his photography that he submitted his work to the magazine Camera and Darkroom, and in the April 1906 issue they published a full-page reproduction of his picture Spring, Chicago. This is the first known publication of any of his photographs.

1906–23: Becoming a photographer

At the urging of his sister, Weston left Chicago in the spring of 1906 and moved near May's home in Tropico, California (now a neighborhood in Glendale). He decided to stay there and pursue a career in photography, but he soon realized he needed more professional training. A year later he moved to Effingham, Illinois, to enroll in the Illinois College of Photography. They taught a nine-month course, but Weston finished all of the class work in six months. The school refused to give him a diploma unless he paid for the full nine months; Weston refused and instead moved back to California in the spring of 1908.

He briefly worked at the photography studio of George Steckel in Los Angeles, as a negative retoucher. Within a few months he moved to the more established studio of Louis Mojonier. For the next several years he learned the techniques and business of operating a photography studio under Mojonier's direction.

Within days of his visit to Tropico, Weston was introduced to his sister's best friend, Flora May Chandler. She was a graduate of the Normal School, later to become UCLA. She assumed the position of a grade-school teacher in Tropico. She was seven years older than Weston and a distant relative of Harry Chandler, who at that time was described as the head of "the single most powerful family in Southern California". This fact did not go unnoticed by Weston and his biographers.

On January 30, 1909, Weston and Chandler married in a simple ceremony. The first of their four sons, Edward Chandler Weston (1910–1993), known as Chandler, was born on April 26, 1910. Named Edward Chandler, after Weston and his wife, he later became an excellent photographer on his own. He clearly learned much by being an assistant to his father in the bungalow studio. In 1923 he bid farewell to his mother and sibling brothers and sailed off to Mexico with his father and Tina Modotti. He gave up any aspirations in pursuing photography as a career after his adventures in Mexico. The lifestyle of fame and its fortune affected him greatly. His later photographs, as a hobbyist, albeit rare, certainly reflect an innate talent for the form.

In 1910 Weston opened his own business, called "The Little Studio", in Tropico. His sister later asked him why he opened his studio in Tropico rather than in the nearby metropolis of Los Angeles, and he replied "Sis, I'm going to make my name so famous that it won't matter where I live."[6]

For the next three years he worked, alone and sometimes with the assistance of family members in his studio. Even at that early stage of his career he was highly particular about his work; in an interview at that time he said "[photographic] plates are nothing to me unless I get what I want. I have used thirty of them at a sitting if I did not secure the effect to suit me."[7]

His critical eye paid off as he quickly gained more recognition for his work. He won prizes in national competitions, published several more photographs and wrote articles for magazines such as Photo-Era and American Photography, championing the pictorial style.

On December 16, 1911, Weston's second son, Theodore Brett Weston (1911–1993), was born. He became a long-time artistic collaborator with his father and an important photographer on his own.

Sometime in the fall of 1913, Los Angeles photographer, Margrethe Mather visited Weston's studio because of his growing reputation, and within a few months they developed an intense relationship.[8] Weston was a quiet Midwestern transplant to California, and Mather was a part of the growing bohemian cultural scene in Los Angeles. She was very outgoing and artistic in a flamboyant way, and her permissive sexual morals were far different from the conservative Weston at the time – Mather had been a prostitute and was bisexual with a preference for women.[9] Mather presented a stark contrast to Weston's home life; his wife Flora was described as a "homely, rigid Puritan, and an utterly conventional woman, with whom he had little in common since he abhorred conventions"[10] ‒ and he found Mather's uninhibited lifestyle irresistible and her photographic vision intriguing.

He asked Mather to be his studio assistant, and for the next decade they worked closely together, making individual and jointly signed portraits of such luminaries as Carl Sandburg and Max Eastman. A joint exhibition of their work in 2001 revealed that during this period Weston emulated Mather's style and, later, her choice of subjects. On her own Mather photographed "fans, hands, eggs, melons, waves, bathroom fixtures, seashells and birds wings, all subjects that Weston would also explore."[11] A decade later he described her as "the first important person in my life, and perhaps even now, though personal contact has gone, the most important."[12] In early 1915 Weston began keeping detailed journals he later came to call his "Daybooks". For the next two decades he recorded his thoughts about his work, observations about photography, and his interactions with friends, lovers and family. On December 6, 1916, a third son, Lawrence Neil Weston, was born. He also followed in the footsteps of his father and became a well-known photographer. It was during this period that Weston first met photographer Johan Hagemeyer, whom Weston mentored and lent his studio to from time to time. Later, Hagemeyer would return the favor by letting Weston use his studio in Carmel after he returned from Mexico. For the next several years Weston continued to earn a living by taking portraits in his small studio which he called "the shack".[7]

Meanwhile, Flora was spending all of her time caring for their children. Their fourth son, Cole Weston (1919–2003), was born on January 30, 1919, and afterward she rarely had time to leave their home.

Over the summer of 1920 Weston met two people who were part of the growing Los Angeles cultural scene: Roubaix de l'Abrie Richey, known as "Robo" and a woman he called his wife, Tina Modotti. Modotti, who was then known only as a stage and film actress, was never married to Robo, but they pretended to be for the sake of his family. Weston and Modotti were immediately attracted to each other, and they soon became lovers.[13] Richey knew of Modotti's affair, but he continued to be friends with Weston and later invited him to come to Mexico and share his studio.[14]

The following year Weston agreed to allow Mather to become an equal partner in his studio. For several months they took portraits that they signed with both of their names. This was the only time in his long career that Weston shared credit with another photographer.

Sometime in 1920 he began photographing nude models for the first time. His first models were his wife Flora and their children, but soon thereafter he took at least three nude studies of Mather. He followed these with several more photographs of nude models, the first of dozens of figure studies he would make of friends and lovers over the next twenty years.

Until now Weston had kept his relationships with other women a secret from his wife, but as he began to photograph more nudes Flora became suspicious about what went on with his models. Chandler recalled that his mother regularly sent him on "errands" to his father's studio and asked him to tell her who was there and what they were doing.[15]

.jpg)

One of the first who agreed to model nude for Weston was Modotti. She became his primary model for the next several years.

In 1922 he visited his sister May, who had moved to Middletown, Ohio. While there he made five or six photographs of the tall smoke stacks at the nearby Armco steel mill. These images signaled a change in Weston's photographic style, a transition from the soft-focus pictorialism of the past to a new, cleaner-edge style. He immediately recognized the change and later recorded it in his notes: "The Middletown visit was something to remember...most of all in importance was my photographing of 'Armco'...That day I made great photographs, even Stieglitz thought they were important!"[16]

At that time New York City was the cultural center for photography as an art form in America, and Alfred Stieglitz was the most influential figure in photography.[17] Weston badly wanted to go to New York to meet with him, but he did not have enough money to make the trip. His brother-in-law gave him enough money to continue on from Middletown to New York City, and he spent most of October and early November there. While there he met artist Charles Sheeler, photographers Clarence H. White, Gertrude Kasebier and finally, Stieglitz. Weston wrote that Stieglitz told him, "Your work and attitude reassures me. You have shown me at least several prints which have given me a great deal of joy. And I can seldom say that of photographs."[18]

Soon after Weston returned from New York, Robo moved to Mexico and set up a studio there to create batiks. Within a short while he had arranged for a joint exhibition of his work and of photographs by Weston, Mather and a few others. In early 1923 Modotti left by train to be with Robo in Mexico, but he contracted smallpox and died shortly before she arrived. Modotti was grief-stricken, but within a few weeks she felt well enough that she decided to stay and carry out the exhibition that Robo had planned. The show was a success, and, due in no small part to his nude studies of Modotti, it firmly established Weston's artistic reputation in Mexico.[19]

After the show closed Modotti returned to California, and Weston and she made plans to return to Mexico together. He wanted to spend a couple of months there photographing and promoting his work, and, conveniently, he could travel under the pretense of Modotti being his assistant and translator.[20]

The week before he left for Mexico, Weston briefly reunited with Mather and took several nudes of her lying in the sand at Redondo Beach. These images were very different from his previous nude studies – sharply focused and showing her entire body in relation to the natural setting. They have been called the artistic prototypes for his most famous nudes, those of Charis Wilson which he would take more than a decade later.[21]

1923–27: Mexico

On July 30, 1923, Weston, his son Chandler, and Modotti left on a steamer for the extended trip to Mexico. His wife, Flora, and their other three sons waved goodbye to them at the dock. It's unknown what Flora understood or thought about the relationship between Weston and Modotti, but she is reported to have called out at the dock, "Tina, take good care of my boys."[22]

They arrived in Mexico City on August 11 and rented a large hacienda outside of the city. Within a month he had arranged for an exhibition of his work at the Aztec Land Gallery, and on October 17 the show opened to glowing press reviews. He was particularly proud of a review by Marius de Zayas that said "Photography is beginning to be photography, for until now it has only been art."[23]

The different culture and scenery in Mexico forced Weston to look at things in new ways. He became more responsive to what was in front of him, and he turned his camera on everyday objects like toys, doorways and bathroom fixtures. He also made several intimate nudes and portraits of Modotti. He wrote in his Daybooks:

- The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself...I feel definite in the belief that the approach to photography is through realism.[24]

Weston continued to photograph the people and things around him, and his reputation in Mexico increased the longer he stayed. He had a second exhibition at the Aztec Land Galley in 1924, and he had a steady stream of local socialites asking him to take their portraits. At the same time, Weston began to miss his other sons back in the U.S. As with many of his actions, though, it was a woman who motivated him most. He had recently corresponded with a woman he had known for several years named Miriam Lerner, and as her letters became more passionate he longed to see her again.[25]

He and Chandler returned to San Francisco at the end of 1924, and the next month he set up a studio with Hagemeyer. Weston seemed to be struggling with his past and his future during this period. He burned all of his pre-Mexico journals, as though trying to erase the past, and started a new series of nudes with Lerner and with his son Neil. He wrote that these images were "the start of a new period in my approach and attitude towards photography."[25]

His new relationship with Lerner did not last long, and in August 1925 he returned to Mexico, this time with his son Brett. Modotti had arranged a joint show of their photographs, and it opened the week he returned. He received new critical acclaim, and six of his prints were purchased for the State Museum. For the next several months he concentrated once again on photographing folk art, toys and local scenes. One of his strongest images of this period is of three black clay pots that art historian Rene d'Harnoncourt described as "the beginning of a new art."[26]

In May 1926 Weston signed a contract with writer Anita Brenner for $1,000 to make photographs for a book she was writing about Mexican folk art. In June he, Modotti and Brett started traveling around the country in search of lesser known native arts and crafts. His contract required him to give Brenner three finished prints from 400 8x10 negatives, and it took him until November of that year to complete the work.[27] During their travels, Brett received a crash course in photography from his father, and he made more than two dozen prints that his father judged to be of exceptional quality.

By the time they returned from their trip, Weston and Modotti's relationship had crumbled, and within less than two weeks he and Brett returned to California. He never traveled to Mexico again.

1927–35: Glendale to Carmel

Weston initially returned to his old studio in Glendale (previously called Tropico). He quickly arranged a dual exhibition at University of California of the photographs that he and Brett had made the year before. The father showed 100 prints and the son showed 20. Brett was only 15 years old at the time.

In February he started a new series of nudes, this time of dancer Bertha Wardell. One of this series, of her kneeling body cut off at the shoulders, is one of Weston's most well-known figure studies. At this same time he met Canadian painter Henrietta Shore, whom he asked to comment on the photos of Wardell. He was surprised by her honest critique: "I wish you would not do so many nudes – you are getting used to them, the subject no longer amazes you ‒ most of these are just nudes."[28]

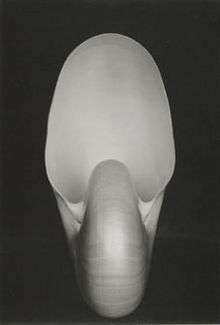

He asked to look at her work and was intrigued by her large paintings of sea shells. He borrowed several shells from her, thinking he might find some inspiration for a new still life series. Over the next few weeks he explored many different kinds of shell and background combinations – in his log of photographs taken for 1927 he listed fourteen negatives of shells.[29] One of these, simply called Nautilus, 1927" (sometimes called Shell, 1927), became one of his most famous images. Modotti called the image "mystical and erotic,"[30] and when she showed it to Rene d'Harnoncourt he said he felt "weak at the knees."[31] Weston is known to have made at least twenty-eight prints of this image, more than he had made of any other shell image.[29]

In September of that year Weston had a major exhibition at Palace of the Legion of Honor. At the open of the show he met fellow photographer Willard Van Dyke, who later introduced Weston to Ansel Adams.

In May 1928, Weston and Brett made a brief but important trip to the Mojave Desert. It was there that he first explored and photographed landscapes as an art form.[32] He found the stark rock forms and empty spaces to be a visual revelation, and over a long weekend he took twenty-seven photographs.[33] In his journal he declared "these negatives are the most important I have ever done."[34]

Later that year he and Brett moved to San Francisco, where they lived and worked in a small studio owned by Hagemeyer. He made portraits to earn an income, but he longed to get away by himself and get back to his art. In early 1929 he moved to Hagemeyer's cottage in Carmel, and it was there that he finally found the solitude and the inspiration that he was seeking. He placed a sign in studio window that said, "Edward Weston, photographer, Unretouched Portraits, Prints for Collectors."

He started making regular trips to nearby Point Lobos, where he would continue to photograph until the end of his career. It was there that he learned to fine-tune his photographic vision to match the visual space of his view camera, and the images he took there, of kelp, rocks and wind-blown trees, are among his finest. Looking at his work from this period, one biographer wrote:

- "Weston arranged his compositions so that things happened on the edges; lines almost cross or meet and circular lines just touch the edges tangentially; his compositions were now created exclusively for a space with the proportions of eight by ten. There is no extraneous space nor is there too little."[35]

In early April 1929, Weston met photographer Sonya Noskowiak at a party, and by the end of the month she was living with him. As with many of his other relationships, she became his model, muse, pupil and assistant. They would continue to live together for five years.

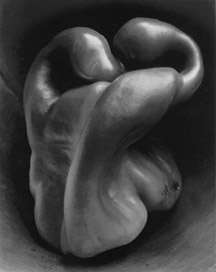

Intrigued by the many kinds and shapes of kelp he found on the beaches near Carmel, in 1930 Weston began taking close-ups of vegetables and fruits. He made a variety of photographs of cabbage, kale, onions, bananas, and finally, his most iconic image, peppers. In August of that year Noskowiak brought him several green peppers, and over a four-day period he shot at least thirty different negatives. Of these, Pepper No. 30, is among the all-time masterpieces of photography.[36]

Weston had a series of important one-man exhibitions in 1930–31. The first was at Alma Reed's Delphic Studio Galley in New York, followed closely by a mounting of the same show at the Denny Watrous Gallery in Carmel. Both received rave reviews, including a two-page article in the New York Times Magazine.[35] These were followed by shows at De Young Museum in San Francisco and the Galerie Jean Naert in Paris.

Although he was succeeding professionally his personal life was very complex. For most of their marriage, Flora was able to take care of their children because of an inheritance from her parents. However, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 had wiped out most of her savings, and Weston felt increased pressure to help provide more for her and his sons. He described this time as "the most trying economic period of my life."[35]

In 1932, The Art of Edward Weston, the first book devoted exclusively to Weston's work, was published. It was edited by Merle Armitage and dedicated to Alice Rohrer, an admirer and patron of Weston whose $500 donation helped pay for the book to be published.

During the same time a small group of like-minded photographers in the San Francisco area, led by Van Dyke and Ansel Adams, began informally meeting to discuss their common interest and aesthetics. Inspired by Weston's show at the De Young Museum the previous year, they approached the museum with the idea of mounting a group exhibition of their work. They named themselves Group f/64, and in November 1932, an exhibition of 80 of their prints opened at the museum. The show was a critical success.

In 1933 Weston bought a 4 × 5 Graflex camera, which was much smaller and lighter than the large view camera he had used for many years. He began taking close-up nudes of Noskowiak and other models. The smaller camera allowed him to interact more with his models, while at the same time the nudes he took during this period began to resemble some of the contorted root and vegetables he had taken the year before.[37]

In early 1934, "a new and important chapter opened"[38] in Weston's life when he met Charis Wilson at a concert. Even more than with his previous lovers, Weston was immediately captivated by her beauty and her personality. He wrote: "A new love came into my life, a most beautiful one, one which will, I believe, stand the test of time."[39] On April 22 he photographed her nude for the first time, and they entered into an intense relationship. He was still living with Noskowiak at that time, but within two weeks he asked her to move out, declaring that for him other women were "as inevitable as the tides".[39]

Perhaps because of the intensity of his new relationship, he stopped writing in his Daybooks at this same time. Six months later he wrote one final entry, looking back from April 22:

- After eight months we are closer together than ever. Perhaps C. will be remembered as the great love of my life. Already I have achieved certain heights reached with no other love.[39]

1935–45: Guggenheim grant to Wildcat Hill

In January 1935 Weston was facing increasing financial difficulties. He closed his studio in Carmel and moved to Santa Monica Canyon, California, where he opened a new studio with Brett. He implored Wilson to come and live with him, and in August 1935 she finally agreed. While she had an intense interest in his work, Wilson was the first woman Weston had lived with since Flora who had no interest in becoming a photographer.[40] This allowed Weston to concentrate on her as his muse and model, and in turn Wilson devoted her time to promoting Weston's art as his assistant and quasi-agent.

Almost immediately he began taking a new series of nudes with Wilson as the model. One of the first photographs he took of her, on the balcony of their home, became one of his most published images (Nude (Charis, Santa Monica)). Soon after they took the first of several trips to Oceano Dunes. It was there that Weston made some of his most daring and intimate photographs of any of his models, capturing Wilson in completely uninhibited poses in the sand dunes. He exhibited only one or two of this series in his lifetime, thinking several of the others were "too erotic"[41] for the general public.

Although his recent work had received critical acclaim, he was not earning enough income from his artistic images to provide a steady income. Rather than going back to relying solely on portraiture, he started the "Edward Weston Print of the Month Club", offering selections of his photos for a monthly $5 subscription. Each month subscribers would receive a new print from Weston, with a limited edition of 40 copies of each print. Although he created these prints with the same high standards that he did for his exhibition prints, it is thought that he never had more than eleven subscribers.[40]

At the suggestion of Beaumont Newhall, Weston decided to apply for a Guggenheim Foundation grant (now known as a Guggenheim Fellowship). He wrote a two-sentence description about his work, assembled thirty-five of his favorites prints, and sent it in.[42] Afterward Dorothea Lange and her husband suggested that the application was too brief to be seriously considered, and Weston resubmitted it with a four-page letter and work plan. He did not mention that Wilson had written the new application for him.[43]

On March 22, 1937, Weston received notification that he had been awarded a Guggenheim grant, the first ever given to a photographer.[44] The award was $2,000 for one year, a significant amount of money at that time. He was able to further capitalize on the award by arranging to provide the editor of AAA Westway Magazine with 8–10 photos per month for $50 during their travels, with Wilson getting an additional $15 monthly for photo captions and short narratives. They purchased a new car and set out on Weston's dream trip to go and photograph whatever he wanted. Over the next twelve months they made seventeen trips and covered 16,697 miles according to Wilson's detailed log. Weston made 1,260 negatives during the trip.

The freedom of this trip with the "love of his life", combined with all of his sons now reaching the age of adulthood, gave Weston the motivation to finally divorce his wife. They had been living apart for sixteen years.[45]

Due to the success of the past year, Weston applied for and received a second year of Guggenheim support. Although he wanted to do some additional traveling, he intended to use most of the money to allow him to print his past year's work. He commissioned Neil to build a small home in the Carmel Highlands on property owned by Wilson's father. They named the place "Wildcat Hill" because of the many domestic cats that soon occupied the grounds.

Wilson set up a writing studio in what was intended to be a small garage behind the house, and she spent several months writing and editing stories from their travels.

In 1939, Seeing California with Edward Weston was published, with photographs by Weston and writing by Wilson. Finally relieved from the financial stresses of the past and inordinately happy with his work and his relationship, Weston married Wilson in a small ceremony on April 24.

Buoyed by the success of their first book, in 1940 they published California and the West. The first edition, featuring 96 of Weston's photos with text by Wilson, sold for $3.95. Over the summer, Weston taught photography at the first Ansel Adams Workshop at Yosemite National Park.

Just as the Guggenheim money was running out, Weston was invited to illustrate a new edition of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. He would receive $1,000 for photographs and $500 travel expenses. Weston insisted on having artistic control of the images he would take and insisted that he would not be taking literal illustrations of Whitman's text. On May 28 he and Wilson began a trip that would cover 20,000 miles through 24 states; he took between 700 and 800 8x10 negatives as well as dozens of Graflex portraits.[46]

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and the United States entered World War II. Weston was near the end of the Whitman trip, and he was deeply affected by the outbreak of the war. He wrote: "When the war broke out we scurried home. Charis did not want to scurry. I did."[47]

He spent the first few months of 1942 organizing and printing the negatives from the Whitman trip. Of the hundreds of images he took, forty-nine were selected for publication.

Due to the war, Point Lobos was closed to the public for several years. Weston continued to work on images centered on Wildcat Hill, including shots of the many cats that lived there. Weston treated them with the same serious intent that he applied to all of his other subjects, and Charis assembled the results into their most unusual publication, The Cats of Wildcat Hill, which was finally published in 1947.

The year 1945 marked the beginning of significant changes for Weston. He began to experience the first symptoms of Parkinson's disease, a debilitating ailment that gradually stole his strength and his ability to photograph. He withdrew from Wilson, who at the same time began to become more involved in local politics and the Carmel cultural scene. A strength that originally brought them together – her lack of interest in becoming a photographer herself – eventually led to their break-up. She wrote, "My flight from Edward was also partly an escape from photography, which had taken up so much room in my life for so many years."[48]

While working on a major retrospective exhibition for the Museum of Modern Art, he and Wilson separated. Weston returned to Glendale since the land for their cabin at Wildcat Hill still belonged to Wilson's father. Within a few months she moved out and arranged to sell the property to him.

1946–58: Final years

In February 1946, Weston's major retrospective opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He and Beaumont Newhall selected 313 prints for the exhibition, and eventually 250 photographs were displayed along with 11 negatives. At that time many of his prints were still for sale, and he sold 97 prints from the exhibit at $25 per print. Later that year, Weston was asked by Dr. George L. Waters of Kodak to produce 8 × 10 Kodachrome transparencies for their advertising campaign. Weston had never worked in color before, primarily because he had no means of developing or printing the more complicated color process. He accepted their offer in no small part because they offered him $250 per image, the highest amount he would be paid for any single work in his lifetime.[49] He eventually sold seven color works to Kodak of landscapes and scenery at Point Lobos and nearby Monterey harbor.

In 1947 as his Parkinson's disease progressed, Weston began looking for an assistant. Serendipitously, an eager young photographic enthusiast, Dody Weston Thompson, contacted him in search of employment.

Weston mentioned he had just that morning written a letter to Ansel Adams, looking for someone seeking to learn photography in exchange for carrying his bulky large-format camera and to provide a much needed automobile. There was a swift meeting of creative minds. For the remainder of 1947 through the beginning of 1948, Dody commuted from San Francisco on weekends to learn from Weston the basics of photography. In early 1948, Dody moved into "Bodie House," the guest cottage at Edward's Wildcat Hill compound, as his full-time assistant.

By late 1948 he was no longer physically able to use his large view camera. That year he took his last photographs, at Point Lobos. His final negative was an image he called, "Rocks and Pebbles, 1948". Although diminished in his capacity, Weston never stopped being a photographer. He worked with his sons and Dody to catalog his images and especially to oversee the publication and printing of his work. In 1950 there was a major retrospective of his work at the Musee National d'Art Moderne in Paris, and in 1952 he published a Fiftieth Anniversary portfolio, with images printed by Brett.

During this time he worked with Cole, Brett, and Dody Thompson (Brett's wife by 1952), to select and have them print a master set of what he considered his best work. They spent many long hours together in the darkroom, and by 1956 they had produced what Weston called "The Project Prints", eight sets of 8" × 10" prints from 830 of his negatives. The only complete set today is housed at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Later that same year the Smithsonian Institution displayed nearly 100 of these prints at a major exhibit, "The World of Edward Weston", paying tribute to his accomplishments in American photography.

Weston died at his home on Wildcat Hill on New Year's Day, 1958. His sons scattered his ashes into the Pacific Ocean at an area then known as Pebbly Beach on Point Lobos. Due to Weston's significant influence in the area, the beach was later renamed Weston Beach. He had $300 in his bank account at the time of his death.[50]

Equipment and techniques

Cameras and lenses

During his lifetime Weston worked with several cameras. He began as a more serious photographer in 1902 when he purchased a 5 × 7 camera.[51] When he moved to Tropico, now part of Glendale, and opened his studio in 1911, he acquired an enormous 11 x 14 Graf Variable studio portrait camera. Roi Partridge, Imogen Cunningham's husband, later made an etching of Weston in his studio, dwarfed by the giant camera in front of him.[52] After he began taking more portraits of children, he bought a 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ Graflex in 1912 to better capture their quickly changing expressions.[53]

When he went to Mexico in 1924 he took an 8 × 10 Seneca folding-bed view camera with several lenses, including a Graf Variable and a Wollensak Verito. While in Mexico he purchased a used Rapid Rectilinear lens which was his primary lens for many years. The lens, now in the George Eastman House, did not have a manufacturer's name.[54] He also took to Mexico a 3¼ × 4¼ Graflex with a ƒ/4.5 Tessar lens, which he used for portraits.

In 1933 he purchased a 4 × 5 R. B. Auto-Graflex and used it thereafter for all portraits.[55] He continued to use the Seneca view camera for all other work.

In 1939 he listed the following items as his standard equipment:[55]

- 8 x 10 Century Universal

- Triple convertible Turner Reich, 12", 21", 28"

- K2, G, A filters

- 12 film holders

- Paul Ries Tripod

He continued to use this equipment throughout his life.

Film

Prior to 1921 Weston used an orthochromatic sheet film, but when panchromatic film became widely available in 1921 he switched to it for all of his work. According to his son Cole, after Agfa Isopan film came out in the 1930s Weston used it for his black-and-white images for the rest of his life.[56] This film was rated at about ISO 25, but the developing technique Weston used reduced the effective rating to about ISO 12.[57]

The 8 × 10 cameras he preferred were large and heavy, and due to the weight and the cost of the film he never carried more than twelve sheet film holders with him. At the end of each day, he had to go into a darkroom, unload the film holders and load them with new film. This was especially challenging when he was traveling since he had to find a darkened room somewhere or else set up a makeshift darkroom made from heavy canvas.[58]

In spite of the bulky size of the view camera, Weston boasted he could "set up the tripod, fasten the camera securely to it, attach the lens to the camera, open the shutter, study the image on the ground glass, focus it, close the shutter, insert the plate holder, cock the shutter, set it to the appropriate aperture and speed, remove the slide from the plate holder, make the exposure, replace the slide, and remove the plate holder in two minutes and twenty seconds."[58]

The smaller Graflex cameras he used had the advantage of using film magazines that held either 12 or 18 sheets of film. Weston preferred these cameras when taking portraits since he could respond more quickly to the sitter. He reported that with his Graflex he once made three dozen negatives of Tina Modotti within 20 minutes.[59]In 1946 a representative from Kodak asked Weston to try out their new Kodachrome film, and over the next two years he made at least 60 8 x 10 color images using this film."[60] They were some of the last photographs he took, since by late 1948 he was no longer able to operate a camera due to the effects of his Parkinson's disease.

Exposures

During the first 20 years of his photography Weston determined all of his exposure settings by estimation based on his previous experiences and the relatively narrow tolerances of the film at that time. He said, "I dislike to figure out time, and find my exposures more accurate when only "felt"."[61] In the late 1930s he acquired a Weston exposure meter and continued to use it as an aid to determine exposures throughout his career.[note 1] Photo historian Nancy Newhall wrote that "Young photographers are confused and amazed when they behold him measuring with his meter every value in the sphere where he intends to work, from the sky to the ground under his feet. He is "feeling the light" and checking his own observations. After which he puts the meter away and does what he thinks. Often he adds up everything ‒ filters, extension, film, speed, and so on ‒ and doubles the computation."[62] Weston, Newhall noted, believed in "massive exposure", which he then compensated for by hand-processing the film in a weak developer solution and individually inspecting each negative as it continued to develop to get the right balance of highlights and shadows.[62]

The low ISO rating of the sheet film Weston used necessitated very long exposures when using his view camera, ranging from 1 to 3 seconds for outdoor landscape exposures to as long as 4½ hours for still lifes such as peppers or shells.[63] When he used one of the Graflex cameras the exposure times were much shorter (usually less than ¼ second), and he was sometimes able to work without a tripod.[64]

Darkroom

Weston always made contact prints, meaning that the print was exactly the same size as the negative. This was essential for the platinum printing that he preferred early in his career, since at that time the platinum papers required ultra-violet light to activate. Weston did not have an artificial ultra-violet light source, so he had to place the contact print directly in sunlight to expose it.[64] This limited him to printing only on sunny days.

When he wanted a print that was larger than the original negative size, he used an enlarger to create a larger inter-positive, then contact printed it to a new negative. The new larger negative was then used to make a print of that size.[65] This process was very labor-intensive; he once wrote in his Daybooks "I am utterly exhausted tonight after a whole day in the darkroom, making eight contact negatives from the enlarged positives."[66]

In 1924 Weston wrote this about his darkroom process, "I have returned, after several years use of Metol-Hydroquinine open-tank" developer to a three-solution Pyro developer, and I develop one at a time in a tray instead of a dozen in a tank."[61] Each sheet of film was viewed under either a green or an orange safelight in his darkroom, allowing him to control the individual development of a negative. He continued to use this technique for the rest of his life.

Weston was known to extensively use dodging and burning to achieve the look he wanted in his prints.[67][57]

Paper

Early in his career Weston printed on several kinds of paper, including Velox, Apex, Convira, Defender Velour Black and Haloid.[57] When he went to Mexico he learned how to use platinum and palladium paper, made by Willis & Clement and imported from England.[61] After his return to California, he abandoned platinum and palladium printing due to the scarcity and increasing price of the paper. Eventually he was able to get most of the same qualities he preferred with Kodak's Azo glossy silver gelatin paper developed in Amidol.[61] He continued to use this paper almost exclusively until he stopped printing.

Writings

Weston was a prolific writer. His Daybooks were published in two volumes totaling more than 500 pages in the first edition. This does not include the years of the journal he kept between 1915 and 1923; for reasons he never made clear he destroyed those before leaving for Mexico.[68] He also wrote dozens of articles and commentaries, beginning in 1906 and ending in 1957,[69] and he hand-wrote or typed at least 5,000 letters to colleagues, friends, lovers, his wives and his children.[70]

In addition, Weston kept very thorough notes on the technical and business aspects of his work. The Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, which now houses most of Weston's archives, reports that it houses 75 linear feet of pages from his Daybooks, correspondence, financial records, memorabilia, and other personal documents in his possession when he died.[71]

Among Weston's most important early writings are those that provide insights into his development of the concept of previsualization. He first spoke and wrote about the concept in 1922, at least a decade before Ansel Adams began utilizing the term, and he continued to expand upon this idea both in writing and in his teachings. Historian Beaumont Newhall noted the significance of Weston's innovation in his book The History of Photography, saying "The most important part of Edward Weston's approach was his insistence that the photographer should previsualize the final print before making the exposure."[72]

In his Daybooks he provided an unusually detailed record of his evolution as an artist. Although he initially denied that his images reflect his own interpretations of the subject matter, by 1932 his writings revealed that he had come to accept the importance of artistic impression in his work.[73] When combined with his photographs, his writings provide an extraordinarily vivid series of insights into his development as an artist and his impact of future generations of photographers.

Quotations

- "Form follows function." Who said this I don't know, but the writer spoke well.[74]

- I am not a technician and have no interest in technique for its own sake. If my technique is adequate to present my seeing then I need nothing more.[75]

- I see no reason for recording the obvious.[76]

- If there is symbolism in my work, it can only be the seeing of parts ‒ fragments ‒ as universal symbols. All basic forms are so closely related as to be visually equivalent.[77]

- My own eyes are no more than scouts on a preliminary search, for the camera's eye may entirely change my idea.[78]

- My work-purpose, my theme, can most nearly be stated as the recognition, recording and presentation of the interdependence, the relativity, of all things ‒ the universality of basic form.[79]

- The camera sees more than the eye, so why not make use of it?[80]

- This then: to photograph a rock, have it look like a rock, but be more than a rock.[81]

- What then is the end toward which I work? To present the significance of facts, so that they are transformed from things seen to things known.[82]

- When money enters in ‒ then, for a price, I become a liar ‒ and a good one I can be whether with pencil or subtle lighting or viewpoint. I hate it all, but so do I support not only my family, but my own work.[83]

Legacy

As of 2013, two of Weston's photographs feature among the most expensive photographs ever sold. The Nude, 1925 taken in 1925 was bought by the gallerist Peter MacGill for $1.6 million in 2008.[84] Nautilus of 1927 was sold for $1.1 million in 2010, also to MacGill.[85][86]

Major exhibitions

- 1970, the Rencontres d'Arles festival (France) presented an exhibition "Hommage à Edward Weston" and an evening screening of the film The Photographer (1948) by Willard Van Dyke.

- November 25, 1986 – March 29, 1987 Edward Weston in Los Angeles at Huntington Library[87]

- 1986 Edward Weston: Color Photography at Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona[88]

- May 13 – August 27, 1989 Edward Weston in New Mexico at Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe[89]

- Edward Weston : the Last Years in Carmel at The Art Institute of Chicago, June 2 – September 16, 2001, and at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Mar. 1 – July 9, 2002.[90]

List of photographs

The artistic career of Weston spanned more than forty years, from roughly 1915 to 1956. A prolific photographer, he produced more than 1,000 black-and-white photographs and some 50 color images. This list is an incomplete selection of Weston's better-known photographs.

| Title | Year | Category | Dimensions | Collections |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nude | 1918 | Nude | 9.5" x 7.4" / 24.1 x 18.8 cm | Private collection |

| Prologue to a Sad Spring | 1920 | Pictorial | 9.4" x 7.4" / 23.8 x 18.8 cm | Center for Creative Photography, University of California at Santa Cruz, Smithsonian Institution |

| Sunny Corner in the Attic | 1921 | Pictorial | 7.5" x 9.5" / 19 x 24 cm | Center for Creative Photography, University of California at Santa Cruz |

| The White Iris | 1921 | Pictorial | 9.5" x 7.5" / 24.2 x 19 cm | Center for Creative Photography |

| Breast | 1923 | Nude | 7.4" x 9.5" / 18.8 × 23.9 cm | Center for Creative Photography, University of California at Santa Cruz, George Eastman House |

| Pipes and Stacks: Armco, Middletown, Ohio | 1922 | Buildings | 9.4" x 7.5" / 23.9 x 19.1 cm | Center for Creative Photography, University of California at Santa Cruz, Smithsonian Institution, Getty Museum, Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

| Nahui Olin | 1923 | Portrait | 9" x 6.8" / 23.0 × 17.4 cm | Center for Creative Photography, University of California at Santa Cruz, George Eastman House, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Museum of Modern Art |

| Tina [nude on the azotea] | 1923 | Nude | 6.9" x 9.4" / 17.6 × 23.8 cm | Center for Creative Photography, University of California at Santa Cruz, Getty Museum, Art Institute of Chicago |

| Galvin Shooting | 1924 | Portrait | 8.2" x 7.2" / 20.8 × 18.4 cm | Center for Creative Photography, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

| Tina Reciting | 1924 | Portrait | 9.5" x 7.5" / 24.1 × 19.0 cm | Center for Creative Photography, Houston Museum of Fine Arts |

| Nude | 1925 | Nude | 5.1" x 9.3" / 13.0 × 23.5 cm | Private collection (one known print) |

| Excusado | 1925 | Objects | 9.5" x 7.5" / 24.1 × 19.2 cm | Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House |

| Tres Ollas | 1926 | Objects | 9.5" x 7.5" / 19 × 23.9 cm | Center for Creative Photography, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Smithsonian Institution, Philadelphia Art Museum |

| Bertha, Glendale | 1927 | Nude | 9.5" x 7.5" / 18.1 × 20.7 cm | Center for Creative Photography, Getty Museum, Monterey Museum of Art |

| Nautilus | 1927 | Still-life | 9.5" x 7.5" / 23.7 × 18.5 cm | Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House, Museum of Modern Art |

| Two Shells | 1927 | Still-life | 9.5" x 7.4" / 24 × 18.9 cm | Center for Creative Photography, Museum of Modern Art, University of California at Santa Cruz |

| Bedpan | 1930 | Still-life | 9.5" x 7.5" / 23.4 × 13.9 cm | Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House, Getty Museum, University of California at Santa Cruz, Philadelphia Art Museum |

| Cypress, Rock, Stone Crop | 1930 | Landscape | 9.5" x 7.5" / 23.8 × 19 cm | Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House, Museum of Modern Art, University of California at Santa Cruz, Huntington Library |

| José Clemente Orozco | 1930 | Portrait | 9.5" x 7.5" / 24.2 × 18.6 cm | Center for Creative Photography, Getty Museum, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Princeton University Art Museum |

| Pepper No. 30 | 1930 | Still-life | 9.5" x 7.5" / 24.4 × 19.3 cm | Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House, Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, University of California at Santa Cruz, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art |

| Eroded Rock No. 51 | 1930 | Landscape | 9.5" x 7.5" / 24.1 × 23.9 cm | Center for Creative Photography, Huntington Library, University of California at Santa Cruz, University of California at Los Angeles |

| White Raddish | 1933 | Still-life | 9.5" x 7.5" / 24.2 x 19 cm | Center for Creative Photography, George Eastman House, Art Institute of Chicago, University of California at Santa Cruz, University of California at Los Angeles, Huntington Library |

Notes

- The Weston exposure meter was invented by Edward Faraday Weston, an electrical engineer and inventor who was not related to photographer Edward Weston. The Weston meter was introduced in 1932 and was widely used by photographers until production ceased in 1967.

References

- Pitts, 13

- "Edward Weston, 1886–1958". Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- Pitts, 27

- Warren (2008), 10

- Conger (1992), biography, 1

- Foley, 17

- Newhall (1984), 5

- Warren (2001), 10–11

- Warren (2001), 13–15

- Argenteri, Letizia (2003). Tina Modotti, Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 60.

- Warren (2001), 35

- Daybooks, I ,145

- Stark, Amy (January 22, 1986). "The Letters of Tina Modotti to Edward Weston". The Archive: 14–15.

- Hooks, 50

- Wilson, 59

- Daybooks, I, 8

- Whelan, Richard (2000). Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Writings. Millerton, NY: Aperture. p. ix.

- Daybooks, I, 6

- Hooks, 57

- Hooks, 56

- Warren (2001), 31

- Conger (1992), biography, 8

- Mora, 65

- Daybooks, I, 120

- Conger (1992), Figure 168

- Daybooks, I, 188

- Mora, 68–69

- Daybooks, II, 17

- Conger (1992), Figure 544

- Daybooks, II ,31

- Daybooks, II, 31

- Pitts,20

- Conger (1992), Fig553

- Daybooks, II, 58

- Conger (1992), Biography, 24

- Rosenblum, Naomi (1989). A World History of Photography. NY: Abbeville Press. p. 441.

- Conger (1992), Figure 725

- Weston (1964), II, 283

- Daybooks, II, 283

- Conger (1992), biography, 29

- Conger (1992), Figure 925

- Conger (1992), biography,30

- Ollman, Arthur. "Museum of Photographic Arts. The Model Wife: Excerpts from the book The Model Wife by Arthur Ollman". Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- Pitts, 25

- Maddow, 213

- Conger (1992), biography, 36

- Daybooks, II, 287

- Wilson, 345

- Conger (1992), biography, 43

- Conger (1992), biography, 45

- Conger 1992, p. Biography 1.

- Conger 1992, p. Biography 5.

- Newhall, Nancy (1999). From Adams to Steiglitz, Pioneers of Modern Photography. Aperture. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-89381-372-7.

- Beaumont Newhall. "Edward Weston's Technique", in Newhall 1984, p. 109.

- Bunnell 1983, p. 89.

- Newhall 1984, p. 129.

- Weston, Cole (1978). Jain Kelly (ed.). Darkroom 2. NY: Lustrum. p. 143.

- Newhall 1986, p. 36.

- Newhall 1986, p. 23.

- Pitts, Terence. "Edward Weston: Color Photography" in Edward Weston: Color Photography, 11

- Newhall 1984, p. 110.

- Newhall, Nancy. "Nancy Newhall Comments" in Edward Weston: Color Photography, 29

- Maddow 1973, p. 148.

- Newhall 1986, p. 24.

- Lowe 2004, p. 22.

- Daybooks & I, p. 96.

- Newhall 1986, p. 40.

- "Henry Edward Weston, 1886–1958: A Detailed Chronology". Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- Bunnell, 1984

- Alinder 2014, p. 258.

- "The Edward Weston Archive, 1870–1958". Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Newhall, Beaumont (1983). The History of Photography. NY: Museum of Modern Art. p. 158.

- Rice, Shelley (1976). "The Daybooks of Edward Weston: Art, Experience and Photographic Vision". Art Journal. 36 (2): 126–129. doi:10.1080/00043249.1977.10793338. JSTOR 776160.

- Bunnell 1983, 49

- Bunnell 1983, 149

- Daybooks, II, 252

- Bunnell 1983, 158

- Evans, Harold (1997). Pictures on a Page: Photo-journalism, Graphics and Picture Editing. Pimlico. p. 75. ISBN 978-0712673884.

- Watts, 39

- Jay, Bill (1971). Views on Nudes. Focal Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0240507316.

- Bunnell 1983, 61

- Bunnell 1983, 67

- Newhall 1986, 34

- "Edward Weston's Nude Sells For $1.6 Million at Sotheby's Setting a New Record for the Artist". ArtDaily. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Loring Knoblauch. "Auction Results: Photographs, April 13, 2010 @Sotheby's". Collector Daily. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- "Part I: Sotheby's NYC Sales Hit Over $12.7 Million, Setting New $1.1 Million Record For Edward Weston; Evening Sale Nets Over $6.53 Million On 36 Lots". iPhotoCentral. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Edward Weston in Los Angeles. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library and Art Gallery. 1986. ISBN 978-0-87328-092-1.

- Edward Weston: Color Photography. Tucson, AZ: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. 1986. ISBN 978-0-938262-14-5.

- Edward Westin in New Mexico. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico. 1989.

- Edward Weston: The Last Years in Carmel. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago. 2001.

Sources

- Abbott, Brett. Edward Weston: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005. ISBN 978-0-89236-809-9

- Alinder, Mary Street. Group f.64: Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, and the Community of Artists Who Revolutionized American Photography. New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2014. ISBN 978-1620405550

- Bunnell, Peter C. Edward Weston on Photography. Salt Lake City: P. Smith Books, 1983. ISBN 0-87905-147-7

- Bunnell, Peter C., David Featherston et al. EW 100: Centennial Essays in Honor of Edward Weston. Carmel, Calif. : Friends of Photography, 1986.

- Conger, Amy. Edward Weston in Mexico, 1923–1926. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8263-0665-9

- Conger, Amy (1992). Edward Weston – Photographs From the Collection of the Center for Creative Photography. Tucson: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 1992. ISBN 0-938262-21-1

- Conger, Amy. Edward Weston: The Form of The Nude. NY: Phaidon, 2006. ISBN 0-7148-4573-6

- Edward Weston : Color Photography. Tucson: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 1986. ISBN 0-938262-14-9

- Enyeart, James. Edward Weston's California landscapes. Boston : Little, Brown, 1984.

- Foley, Kathy Kelsey. Edward Weston's Gifts to His Sister. Dayton: Dayton Art Institute, 1978.

- Heyman, There Thau. Seeing Straight: The f.64 Revolution in Photography. Oakland: Oakland Art Museum, 1992.

- Higgins, Gary. Truth, Myth and Erasure: Tina Modotti and Edward Weston. Tempe, Ariz. : School of Art, Arizona State University, 1991.

- Hochberg, Judith and Michael P. Mattis. Edward Weston: Life Work. Photographs from the Collection of Judith G. Hochberg and Michael P. Mattis. Revere, Pa.: Lodima Press, c2003. ISBN 1-888899-09-3

- Hooks, Margaret. Tina Modotti: Photographer and Revolutionary. London: Pandora, 1993.

- Lowe, Sarah M. Tina Modotti and Edward Weston the Mexico Years. London: Merrell, 2004. ISBN 1-85894-245-4

- Maddow, Ben. Edward Weston: Fifty Years; The Definitive Volume of His Photographic Work. Millerton, N.Y., Aperture, 1973. ISBN 0-912334-38-X, ISBN 0-912334-39-8

- Maggia, Filippo. Edward Weston. New York: Skira, 2013. ISBN 978-8857216331

- Mora, Gilles (ed.). Edward Weston: Forms of Passion. NY: Abrams, 1995. ISBN 0-8109-3979-7

- Morgan, Susan. Portraits / Edward Weston. NY: Aperture, 1995. ISBN 0-89381-605-1

- Newhall, Beaumont (1984). Edward Weston Omnibus: A Critical Anthology. Salt Lake City : Peregrine Smith Books, 1984. ISBN 0-87905-131-0

- Newhall, Beaumont . Supreme Instants: The Photography of Edward Weston. Boston : Little, Brown, 1986. ISBN 0-8212-1621-X

- Newhall, Nancy (ed.). Edward Weston; The Flame of Recognition: His Photographs Accompanied by Excerpts from the Daybooks & Letters. NY: Aperture, 1971.

- Pitts, Terence. Edward Weston 1866–1958. Köln: Taschen, 1999. ISBN 978-3-8228-7180-5

- Stebins, Theodore E., Karen Quinn and Leslie Furth. Edward Weston : Photography and Modernism. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1999. ISBN 0-8212-2588-X

- Stebins, Theodore E. Weston's Westons : Portraits and Nudes. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1989. ISBN 0-87846-317-8

- Travis, David. Edward Weston, The Last Years in Carmel. Chicago: Art Institute, 2001. ISBN 0-86559-192-X

- Warren, Beth Gates. Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. ISBN 978-1606060704

- Warren, Beth Gates. Edward Weston's Gifts to His Sister and Other Photographs. NY: Sotheby's, 2008.

- Warren, Beth Gates (2001). Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration. NY: Norton, 2001. ISBN 0-393-04157-3

- Watts, Jennifer A. (ed.). Edward Weston : A Legacy. London: Merrell, 2003. ISBN 1-85894-206-3

- Weston, Edward (1964). The Daybooks of Edward Weston. Edited by Nancy Nehall. NY: Horizon Press, 1961–1964. 2 vols.

- Weston, Edward. My Camera on Point Lobos; 30 Photographs and Excerpts from E. W.’s Daybook. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950.

- Weston, Paulette. Laughing Eyes: a Book of Letters Between Edward and Cole Weston 1923–1946. Carmel: Carmel Publishing Co., 1999. ISBN 1-886312-09-5

- Wilson, Charis. Edward Weston Nudes: His Photographs Accompanied by Excerpts from the Daybooks & Letters. NY : Aperture, 1977. ISBN 0-89381-020-7

- Wilson, Charis. Through Another Lens: My Years with Edward Weston. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998. ISBN 0-86547-521-0

- Woods, John. Dune: Edward & Brett Weston. Kalispell, MT: Wild Horse Island Press, 2003. ISBN 0-9677321-2-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Weston. |

- edward-weston.com

- Edward Weston on IMDb

- Edward Weston Collection at the Center for Creative Photography

- Ben Maddow "Edward Weston Lecture" The Baltimore Museum of Art: Baltimore, Maryland, 1976. Retrieved June 26, 2012

- The Eloquent Nude: The Love and Legacy of Edward Weston and Charis Wilson Documentary concerning Edward Weston, his muse Charis Wilson and photographer Ansel Adams.

- Encyclopædia Britannica