Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass is a poetry collection by American poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892), each poem of which is loosely connected and represents the celebration of his philosophy of life and humanity. Though first published in 1855, Whitman spent most of his professional life writing and rewriting Leaves of Grass,[1] revising it multiple times until his death. This resulted in vastly different editions over four decades—the first edition being a small book of twelve poems, and the last, a compilation of over 400.

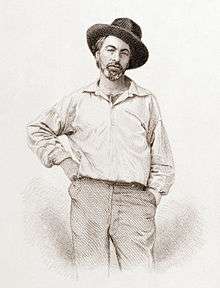

Steel engraving of Walt Whitman, age 37, serving as the frontispiece to Leaves of Grass | |

| Author | Walt Whitman |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Publisher | Self |

Publication date | July 4, 1855 |

| Text | Leaves of Grass at Wikisource |

Influenced by Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalist movement, itself an offshoot of Romanticism, Whitman's poetry praises nature and the individual human's role in it. Rather than relying on symbolism, allegory, and meditation on the religious and spiritual like much of the poetry (especially English poetry) to come before it, Leaves of Grass (particularly the first edition) exalts the body and the material world instead. Much like Emerson, however, Whitman does not diminish the role of the mind or the spirit; rather, he elevates the human form and the human mind, deeming both worthy of poetic praise.

With one exception, its poems do not rhyme or follow standard rules for meter and line length. Among the works in this collection are "Song of Myself", "I Sing the Body Electric", and "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking". Later editions would include Whitman's elegy to the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd".

Leaves of Grass is notable for its discussion of delight in sensual pleasures during a time when such candid displays were considered immoral. Accordingly, the book was highly controversial during its time for its explicit sexual imagery, and Whitman was subject to derision by many contemporary critics. Over time, however, the collection has infiltrated popular culture and been recognized as one of the central works of American poetry.

There have been held to be either six or nine editions of Leaves of Grass, the count depending on how they are distinguished: scholars who hold that an edition is an entirely new set of type will count the 1855, 1856, 1860, 1867, 1871–72, and 1881 printings; whereas others will include the 1876, 1888–89, and 1891–92 (the "deathbed edition")[2] releases.

Publication history and origin

Initial publication, 1855

Leaves of Grass has its genesis in an essay by Ralph Waldo Emerson called "The Poet" (publ. 1844), which expressed the need for the United States to have its own new and unique poet to write about the new country's virtues and vices. Whitman, reading the essay, consciously set out to answer Emerson's call as he began working on the first edition of Leaves of Grass. Whitman, however, downplayed Emerson's influence, stating, "I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil."[3]

On May 15, 1855, Whitman registered the title Leaves of Grass with the clerk of the United States District Court, Southern District of New Jersey, and received its copyright.[4] The title was a pun, as grass was a term given by publishers to works of minor value, and leaves is another name for the pages on which they were printed.[5]

The first edition was published on July 4, 1855, in Brooklyn, at the printing shop of two Scottish immigrants, James and Andrew Rome, whom Whitman had known since the 1840s.[6] The shop was located at Fulton Street (now Cadman Plaza West) and Cranberry Street, now the site of apartment buildings that bear Whitman's name.[7][8] Whitman paid for and did much of the typesetting for the first edition himself. The book did not include the author's name, and instead offered an engraving by Samuel Hollyer depicting Whitman in work clothes and a jaunty hat, arms at his side.[9] Early advertisements for the first edition appealed to "lovers of literary curiosities" as an oddity.[10] Sales on the book were few, but Whitman was not discouraged.

The first edition was very small, collecting only twelve unnamed poems in 95 pages.[5] Whitman once said he intended the book to be small enough to be carried in a pocket. "That would tend to induce people to take me along with them and read me in the open air: I am nearly always successful with the reader in the open air", he explained.[11] About 800 were printed,[12] though only 200 were bound in its trademark green cloth cover.[4] The only American library known to have purchased a copy of the first edition was in Philadelphia.[13] The poems of the first edition, which were given titles in later issues, included:

- "Song of Myself"

- "A Song for Occupations"

- "To Think of Time"

- "The Sleepers"

- "I Sing the Body Electric"

- "Faces"

- "Song of the Answerer"

- "Europe: The 72d and 73d Years of These States"

- "A Boston Ballad"

- "There Was a Child Went Forth"

- "Who Learns My Lesson Complete?" and

- "Great Are the Myths"

Whitman sent a copy of the first edition of Leaves of Grass to Emerson, who had inspired its creation. In a letter to Whitman, Emerson wrote, "I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom America has yet contributed." He went on, "I am very happy in reading it, as great power makes us happy."[14]

Republications, 1856–89

_-_1883_-_Engraving.jpg)

There have been held to be either six or nine editions of Leaves of Grass, the count depending on how they are distinguished: scholars who hold that an edition is an entirely new set of type will count the 1855, 1856, 1860, 1867, 1871–72, and 1881 printings; whereas others will include the 1876, 1888–89, and 1891–92 (the "deathbed edition")[2] releases.

The editions were of varying length, each one larger and augmented from the previous version, until the final edition reached over 400 poems. The 1855 edition is particularly notable for its inclusion of "Song of Myself" and "The Sleepers".

1856–60

It was Emerson's positive response to the first edition that inspired Whitman to quickly produce a much-expanded second in 1856,[14] now 384 pages with a cover price of a dollar.[11] This edition included a phrase from Emerson's letter, printed in gold leaf: "I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career."[11] Emerson later took offense that this letter was made public[15] and became more critical of the work.[16] This edition included "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry", a notable poem.

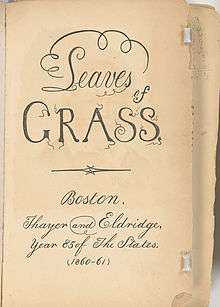

The publishers of the 1860 edition, Thayer and Eldridge, declared bankruptcy shortly after its publication and were almost unable to pay Whitman. "In regard to money matters," they wrote, "we are very short ourselves and it is quite impossible to send the sum." Whitman received only $250, and the original plates made their way to Boston publisher Horace Wentworth.[17] When the 456-page book was finally issued, Whitman said, "It is quite 'odd', of course," referring to its appearance: it was bound in orange cloth with symbols like a rising sun with nine spokes of light and a butterfly perched on a hand.[18] Whitman claimed that the butterfly was real in order to foster his image as being "one with nature." In fact, the butterfly was made of cloth and was attached to his finger with wire.[19] The major poems added to this edition were "A Word Out of the Sea" and "As I Ebb'd With the Ocean of Life".

1867–89

The 1867 edition was intended to be, according to Whitman, "a new & much better edition of Leaves of Grass complete — that unkillable work!"[20] He assumed it would be the final edition.[21] The edition, which included the Drum-Taps section, its Sequel, and the new Songs before Parting, was delayed when the binder went bankrupt and its distributing firm failed. When it was finally printed, it was a simple edition and the first to omit a picture of the poet.[22]

In 1879, Richard Worthington purchased the electrotype plates and began printing and marketing unauthorized copies.

The 1889 (eighth) edition was little changed from the 1881 version, although it was more embellished and featured several portraits of Whitman. The biggest change was the addition of an "Annex" of miscellaneous additional poems.[23]

Sections

By its later editions, Leaves of Grass had grown to fourteen sections.

|

|

|

Earlier editions contained a section called "Chants Democratic"; later editions omitted some of the poems from this section, publishing others in Calamus and other sections.

Deathbed edition, 1892

As 1891 came to a close, Whitman prepared a final edition of Leaves of Grass, writing to a friend upon its completion, "L. of G. at last complete — after 33 y'rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old."[25] This last version of Leaves of Grass was published in 1892 and is referred to as the deathbed edition.[26] In January 1892, two months before Whitman's death, an announcement was published in the New York Herald:

Walt Whitman wishes respectfully to notify the public that the book Leaves of Grass, which he has been working on at great intervals and partially issued for the past thirty-five or forty years, is now completed, so to call it, and he would like this new 1892 edition to absolutely supersede all previous ones. Faulty as it is, he decides it as by far his special and entire self-chosen poetic utterance.[27]

By the time this last edition was completed, Leaves of Grass had grown from a small book of 12 poems to a hefty tome of almost 400 poems.[2] As the volume changed, so did the pictures that Whitman used to illustrate them—the last edition depicts an older Whitman with a full beard and jacket.

Analysis

Whitman's collection of poems in Leaves of Grass is usually interpreted according to the individual poems contained within its individual editions. Discussion is often focused upon the major editions typically associated with the early respective versions of 1855 and 1856, to the 1860 edition, and finally to editions late into Whitman's life. These latter editions would include the poem "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd", Whitman's elegy to Abraham Lincoln after his death.

While Whitman has famously proclaimed (in "Song of Myself") his poetry to be "Nature without check with original energy", scholars have discovered that Whitman borrowed from a number of sources for his Leaves of Grass. For his Drum-Taps, for instance, he lifted phrases from popular newspapers dealing with Civil War battles.[28] He also condensed a chapter from a popular science book into his poem "The World Below the Brine".[29]

In a constantly changing culture, Whitman's literature has an element of timelessness that appeals to the American notion of democracy and equality, producing the same experience and feelings within people living centuries apart.[30] Originally written at a time of significant urbanization in America, Leaves of Grass also responds to the impact such has on the masses.[31] The title metaphor of grass, however, indicates a pastoral vision of rural idealism.

Particularly in "Song of Myself", Whitman emphasizes an all-powerful "I" who serves as narrator. The "I" attempts to relieve both social and private problems by using powerful affirmative cultural images;[32] the emphasis on American culture in particular helped reach Whitman's intention of creating a distinctly American epic poem comparable to the works of Homer.[33]

As a believer in phrenology, Whitman, in the 1855 preface to Leaves of Grass, includes the phrenologist among those he describes as "the lawgivers of poets." Borrowing from the discipline, Whitman uses the phrenological concept of adhesiveness in reference to one's propensity for friendship and camaraderie.[34]

Thematic changes

Whitman edited, revised, and republished Leaves of Grass many times before his death, and over the years his focus and ideas were not static. One critic has identified three major "thematic drifts" in Leaves of Grass: the period from 1855 to 1859, from 1859 to 1865, and from 1866 to his death.

In the first period, 1855 to 1859, his major work is "Song of Myself", which exemplifies his prevailing love for freedom. "Freedom in nature, nature which is perfect in time and place and freedom in expression, leading to the expression of love in its sensuous form."[35] The second period, from 1859 to 1865, paints the picture of a more melancholic, sober poet. In poems like "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" and "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd", the prevailing themes are of love and of death.

From 1866 to his death, the ideas Whitman presented in his second period had experienced an evolution: his focus on death had grown to a focus on immortality, the major theme of this period. Whitman became more conservative in his old age, and had come to believe that the importance of law exceeded the importance of freedom. His materialistic view of the world became far more spiritual, believing that life had no meaning outside of the context of God's plan.[35]

Critical response and controversy

When the book was first published, Walt Whitman was fired from his job at the Department of the Interior, after Secretary of the Interior James Harlan read it and said he found it offensive.[26] An early review of the first publication focused on the persona of the anonymous poet, calling him a loafer "with a certain air of mild defiance, and an expression of pensive insolence on his face."[9] Another reviewer viewed the work as an odd attempt at reviving old Transcendental thoughts, "the speculations of that school of thought which culminated at Boston fifteen or eighteen years ago."[36] Emerson approved of the work in part because he considered it a means of reviving Transcendentalism,[37] though even he urged Whitman to tone down the sexual imagery in 1860.[38]

Poet John Greenleaf Whittier was said to have thrown his 1855 edition into the fire.[14] Thomas Wentworth Higginson wrote, "It is no discredit to Walt Whitman that he wrote Leaves of Grass, only that he did not burn it afterwards."[39] The Saturday Press printed a thrashing review that advised its author to commit suicide.[40]

Critic Rufus Wilmot Griswold reviewed Leaves of Grass in the November 10, 1855, issue of The Criterion, calling it "a mass of stupid filth,"[41] and categorized its author as a filthy free lover.[42] Griswold also suggested, in Latin, that Whitman was guilty of "that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians," one of the earliest public accusations of Whitman's homosexuality.[36] Griswold's intensely negative review almost caused the publication of the second edition to be suspended.[43] Whitman incorporated the full review, including the innuendo, in a later edition of Leaves of Grass.[41]

Not all responses were negative, however. Critic William Michael Rossetti considered Leaves of Grass a classic along the lines of the works of William Shakespeare and Dante Alighieri.[44] A woman from Connecticut named Susan Garnet Smith wrote to Whitman to profess her love for him after reading Leaves of Grass and even offered him her womb should he want a child.[45] Though he found much of the language "reckless and indecent," critic and editor George Ripley believed "isolated portions" of Leaves of Grass radiated "vigor and quaint beauty."[46]

Whitman firmly believed he would be accepted and embraced by the populace, especially the working class. Years later, he would regret not having toured the country to deliver his poetry directly by lecturing:[47]

If I had gone directly to the people, read my poems, faced the crowds, got into immediate touch with Tom, Dick, and Harry instead of waiting to be interpreted, I'd have had my audience at once.

1882

On March 1, 1882, Boston district attorney Oliver Stevens wrote to Whitman's publisher, James R. Osgood, that Leaves of Grass constituted "obscene literature." Urged by the New England Society for the Suppression of Vice, his letter said:

We are of the opinion that this book is such a book as brings it within the provisions of the Public Statutes respecting obscene literature and suggest the propriety of withdrawing the same from circulation and suppressing the editions thereof.

Stevens demanded the removal of the poems "A Woman Waits for Me" and "To a Common Prostitute", as well as changes to "Song of Myself", "From Pent-Up Aching Rivers", "I Sing the Body Electric", "Spontaneous Me", "Native Moments", "The Dalliance of the Eagles", "By Blue Ontario's Shore", "Unfolded Out of the Folds", "The Sleepers", and "Faces".[48]

Whitman rejected the censorship, writing to Osgood, "The list whole & several is rejected by me, & will not be thought of under any circumstances." Osgood refused to republish the book and returned the plates to Whitman when suggested changes and deletions were ignored.[26] The poet found a new publisher, Rees Welsh & Company, which released a new edition of the book in 1882.[49] Whitman believed the controversy would increase sales, which proved true. Its banning in Boston, for example, became a major scandal and it generated much publicity for Whitman and his work.[50] Though it was also banned by retailers like Wanamaker's in Philadelphia, this version went through five editions of 1,000 copies each.[51] Its first printing, released on July 18, sold out in a day.[52]

Legacy

Its status as one of the most important collections of American poetry has meant that over time various groups and movements have used Leaves of Grass, and Whitman's work in general, to further their own political and social purposes. For example:

- In the first half of the 20th century, the popular Little Blue Book series introduced Whitman's work to a wider audience than ever before. A series that backed socialist and progressive viewpoints, the publication connected the poet's focus on the common man to the empowerment of the working class.

- During World War II, the American government distributed for free much of Whitman's poetry to their soldiers, in the belief that his celebrations of the American Way would inspire the people tasked with protecting it.

- Whitman's work has also been claimed in the name of racial equality. In a preface to the 1946 anthology I Hear the People Singing: Selected Poems of Walt Whitman, Langston Hughes wrote that Whitman's "all-embracing words lock arms with workers and farmers, Negroes and whites, Asiatics and Europeans, serfs, and free men, beaming democracy to all."[53]

- Similarly, a 1970 volume of Whitman's poetry published by the United States Information Agency describes Whitman as a man who will "mix indiscriminately" with the people. The volume, which was presented for an international audience, attempted to present Whitman as representative of an America that accepts people of all groups.[53]

Nevertheless, Whitman has been criticized for the nationalism expressed in Leaves of Grass and other works. In an essay regarding Whitman's nationalism in the first edition, Nathanael O’Reilly claims that "Whitman's imagined America is arrogant, expansionist, hierarchical, racist and exclusive; such an America is unacceptable to Native Americans, African-Americans, immigrants, the disabled, the infertile, and all those who value equal rights."[54]

In popular culture

Film and television

- "The Untold Want" features prominently in the Academy Award-winning 1942 film Now, Voyager, starring Claude Rains, Bette Davis, and Paul Henreid.[55]

- Prior to his book, Ray Bradbury used the title of "I Sing the Body Electric" for a 1962 episode he wrote for The Twilight Zone.[56]

- Dead Poets Society (1989) makes repeated references to the poem "O Captain! My Captain!", along with other references to Whitman himself.[57]

- Leaves of Grass plays a prominent role in the American television series Breaking Bad. Episode eight of season five ("Gliding Over All", after poem 271 of Leaves of Grass) pulls together many of the series' references to Leaves of Grass, such as the fact that Walter White has the same initials as Walt Whitman (as noted in episode four of season four, "Bullet Points", and made more salient in "Gliding Over All"), that leads Hank Schrader to realize Walt is Heisenberg. Numerous reviewers have analyzed and discussed the various connections among Walt Whitman/Leaves of Grass/"Gliding Over All", Walt, and the show.[58][59][60]

- In Peace, Love & Misunderstanding (2011), Leaves of Grass is read by Jane Fonda and Elizabeth Olsen's characters.[61]

- In season 3, episode 8, of the BYUtv series Granite Flats, Timothy gives Madeline a first-edition copy of Leaves of Grass as a Christmas gift.[62]

- American singer Lana Del Rey quotes some verses from Whitman's "I Sing the Body Electric" in her short film Tropico (2013).[63]

Literature

- "I Sing the Body Electric" was used by author Ray Bradbury as the title of both a 1969 short story and the book it appeared in (I Sing the Body Electric!), after first appearing as the title of an episode Bradbury wrote in 1962 for The Twilight Zone (I Sing the Body Electric).[56]

- Leaves of Grass features prominently in Lauren Gunderson's American Theatre Critics Association award-winning play I and You (2013).[64]

- Roger Zelazny's time-travel novel Roadmarks features a cybernetically-enhanced edition of Leaves of Grass, one of two such in the story, that acts as a side character giving the protagonist advice and quoting the original. The other "book" is Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal.[65]

- Leaves of Grass appears in John Green's novel Paper Towns, in which the poem "Song of Myself" plays a particularly noteworthy role in the plot.[66]

Music

- "A Sea Symphony" (Symphony No.1) by Ralph Vaughan Williams contains text from Leaves of Grass, written between 1903–1909.[67]

- I Sing the Body Electric (1972) is the second album released by Weather Report.[68]

- Leaves of Grass: A Choral Symphony was composed by Robert Strassburg in 1992.[69]

- American singer Lana Del Rey references Walt Whitman and Leaves of Grass in her song "Body Electric", from her EP Paradise (2012).[70]

Other uses

- In 1997, American President Bill Clinton made a gift of Leaves of Grass to Monica Lewinsky prior to the unfolding of their affair.[71]

References

- Miller, 57

- "Leaves of Grass". World Digital Library. 1855. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Reynolds, 82

- Kaplan, 198

- Loving, 179

- Reynolds, 310

- "A Gesture in Cranberry Street". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 1, 1931. p. 18. Retrieved October 27, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "MTA Neighborhood Maps: neighborhood". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- Callow, 227

- Reynolds, 305

- Reynolds, 352

- Reynolds, 311

- Nelson, Randy F. (1981). The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc. p. 144. ISBN 0-86576-008-X.

- Miller, 27

- Callow, 236

- Reynolds, 343

- Reynolds, 405

- Kaplan, 250

- "Walt Whitman and Leaves of Grass". The Library of Congress Exhibitions: American Treasures.

- Reynolds, 474

- Loving, 314

- Reynolds, 475

- Miller, 55

- https://poets.org/text/guide-walt-whitmans-leaves-grass. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Reynolds, 586

- Miller, 36

- Kaplan, 51

- Genoways, Ted. "Civil War Poems in 'Drum-Taps' and 'Memories of President Lincoln,'" A Companion to Walt Whitman, ed. Donald D. Kummings. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006: 522–538.

- ""The Ever-Changing Nature of the Sea": Whitman's Absorption of Maximilian Schele de Vere". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 30 (2013), 57–77. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- Fisher, Philip (1999). Still the New World: American Literature in a Culture of Creative Destruction. Harvard University Press. p. 66.

- Reynolds, 332

- Reynolds, 324

- Miller, 155

- Mackey, Nathaniel. 1997. "Phrenological Whitman." Conjunctions 29(Fall). Archived from the original on February 2, 2016.

- "A study of thematic drift in Whitman's Leaves of Grass". www.academia.edu. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- Loving, 185

- Loving, 186

- Reynolds, 194

- Broaddus, Dorothy C. (1999). Genteel Rhetoric: Writing High Culture in Nineteenth-Century Boston. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. p. 76. ISBN 1-57003-244-0.

- "Loving Whitman". The New York Times.

- Loving, 184

- Reynolds, 347

- Reynolds, 348

- Loving, 317

- Reynolds, 404

- Crowe, Charles (1967). George Ripley: Transcendentalist and Utopian Socialist. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. p. 246.

- Reynolds, 339

- Loving, 414

- "Rare Books and Special Collections". University of South Carolina Libraries. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- "The Walt Whitman Controversy: A Lost Document". VQR Online. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- Loving, 416

- Reynolds, 543

- "Whitman in Selected Anthologies: The Politics of His Afterlife". VQR Online. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- O’Reilly, Nathanael. "Imagined America: Walt Whitman's Nationalism in the First Edition of 'Leaves of Grass'." Irish Journal of American Studies

- Kenneth M. Price (2005). To Walt Whitman, America. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 120.

- Donald D. Kummings (2009). A Companion to Walt Whitman. John Wiley & Sons. p. 349.

- Michael C. Cohen (2015). The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 163.

- Ryan, Maureen (September 3, 2012). "'Breaking Bad' Finale: Poetic Justice". The Huffington Post. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- Caldwell, Stephanie. "'Breaking Bad' Takes Mid-Season Break". StarPulse. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- Thier, Dave (September 12, 2012). "Breaking Bad "Gliding Over All:" There's No Redemption for Walter White". Forbes.com. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- Andrew Lapin (June 7, 2012). "Movie Review: Back To Woodstock, And To The Spirit Of The '60s". NPR. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "All Truths Wait in All Things". BYUtv. April 4, 2015. Archived from the original on July 16, 2016. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- Duncan Cooper (December 6, 2013). "Why Did Lana Del Rey Make a 30-Minute Video About God, and What Does It Mean for Me?". The Fader.

- Weinert-kendt, Rob (January 6, 2016). "Lauren Gunderson on 'I and You,' a Play With an Explosive Twist". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- Jane M. Lindskold (1993). Roger Zelazny. Twayne Publishers.

- Allie Funk (July 24, 2015). "How 'Paper Towns' Walt Whitman Book Plays A Major Part In Solving The Mystery Of Margo". Bustle.

- "Vaughan Williams: Symphony No.1, 'A Sea Symphony'". Classic FM.

- "The World of Classics & Progressives". Billboard. 84 (32): 21. August 5, 1972.

- Folsom, Ed. "In Memorium: Robert Strasburg 1915–2003". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. University of Iowa Press, Volume #21, November 3, 2004: 189–191

- "Shades of Cool: 12 of Lana Del Rey's Biggest Influences". Rolling Stone. July 16, 2014.

- "Special Report: Clinton Accused". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

Bibliography

- Callow, Philip (1992). From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 0-929587-95-2.

- Kaplan, Justin (1979). Walt Whitman: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22542-1.

- Loving, Jerome (1999). Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22687-9.

- Miller, James E. Jr. (1962). Walt Whitman. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc.

- Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-76709-6.

External links

- Works of Walt Whitman at Curlie

- Leaves of Grass at Project Gutenberg

- "A Guide to Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass" (pdf). Poets.org. January 1, 2000.

- Gould, Mitchel (2003). "Leaves of Grass". leavesofgrass.org.

Walt Whitman's Quaker Paradox

Fan site.