Charis Wilson

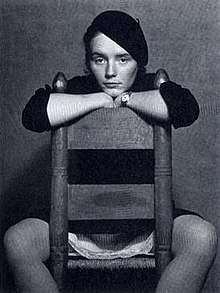

Helen Charis Wilson (/ˈkɛərɪs/; May 5, 1914 – November 20, 2009), was an American model and writer, most widely known as a subject of Edward Weston's photographs.

Early life

Charis Wilson was born in San Francisco, California, the daughter of Harry Leon Wilson and Helen Charis Cooke Wilson. Her father wrote popular fiction, including the bestselling novel Ruggles of Red Gap, which was later made into a movie. Income from his writing provided a relatively high standard of living for the time, and in 1910 he built a 12-room house near Carmel. Two years later, when he was 45, he married Cooke, who grew up in Carmel. She was 16.[1]

Their first child, Leon, was born in 1913 and was followed a year later by their daughter, whom they named after her mother. Wilson dropped her first name as a young girl and became known as Charis, which means 'Grace' in Greek. Her family's relative wealth and status provided her with a leisurely childhood, and she spent many of her summers swimming at the beach at Carmel and often sunbathing without a swim suit. She developed a reputation at school as a boisterous free-thinker for doing such things as starting a "self-control" club in grade school in which initiates had to lie in a tub filled with frigid water.[1] Her behavior led to her being expelled from the private Branson School in the eighth grade, and she spent the next two years at the Catlin Gabel School in Portland, Oregon.

During this time her parents separated, and from then she was cared for primarily by her grandmother and her great aunt, who were both writers and part of the literary scene of San Francisco. She returned to Carmel and finished high school with her brother. While still in high school she met the famous art collectors Louise and Walter Conrad Arensberg, who lived nearby. She visited their home often and was captivated by their substantial collection of modern paintings and sculptures. Walter Arensberg encouraged her by asking for her opinions about art and by engaging her in word play and intellectual puzzles and conundrums. She said later that Arensberg was entirely responsible for her art education.[2]

Her parents divorced when she was 12, and although she was still in school she rarely saw either one of them. She often stayed with her grandmother or great aunt. According to Wilson, Ruth Catlin, founder of the Catlin Gabel School, came to see her and convinced her that she was too bright to stay in Carmel.[1] The two determined she should go back to the Catlin Gabel School to complete her senior year and then go on to Sarah Lawrence College. Her father approved of her returning to Portland to finish high school, but although she won a full scholarship to Sarah Lawrence he refused to allow her to go.[2]

With no other course available to her Wilson went back and forth between San Francisco and Carmel, enrolling in and then dropping out of secretarial school. Due to her father's lack of belief in her, her self-esteem plummeted. She moved into the attic of a painter friend and had a series of love affairs that led to an unwanted pregnancy. Her mother arranged for an abortion, which led her "to resolve on chastity as a new way of life." [1] She wrote that for a while she was driven by "a kind of angry despair…[and was] aware even at the time that I was in bad shape and moving toward worse." [1] It was then that her life changed.

Years with Weston

Weston wrote that at a concert in December 1933 or January 1934 he saw "this tall, beautiful girl, with fine proportioned body, intelligent face, well-freckled, blue eyes, golden brown hair to shoulders – and had to meet."[3] Her brother, Leon, who had met Weston while Wilson was in Portland, introduced the two. Wilson said, "For anyone interested in statistics – I wasn't – he was 48 years old and I had just turned 20. What was important to me was the sight of someone who quite evidently was twice as alive as anyone else in the room, and whose eyes most likely saw twice as much as anyone else's did."[4]

At the time Weston was married, but his wife, Flora Chandler Weston, was living in Los Angeles. In Carmel, Weston was sharing his home with Sonya Noskowiak, a photographer in her own right but also Weston's model and lover. Wilson stopped by Weston's studio a few days later, only to find that Weston had gone to Los Angeles on business. Noskowiak welcomed her, brought out many of Weston's prints for viewing and asked if she would be interested in modeling for Weston. On April 22, 1934, Wilson posed for the first of what would be hundreds of photographs, both nude and clothed.

After the second modeling session, Weston wrote in his daybooks, "a new love come into my life … one which, I believe, will stand the test of time."[3] Posing for Weston elevated Wilson's feelings for him far beyond her initial ardor. She wrote, "During photographic sessions, Edward made a model feel totally aware of herself. It was beyond exhibitionism or narcissism, it was more like a state of induced hypnosis, or of meditation." [4] She became completely enamored of Weston, and he of her. Within a few months time they were lovers. Noskowiak, who was still living with Weston at the time, seemed to be aware of their relationship but might have tolerated it in the hopes that it would not last.

After the initial modeling sessions Weston became completely captivated by Wilson. He made 31 photographs of her nude form in 1934 alone, each laboriously visualized and captured with his 4 X 5 Graflex camera, then hand developed and printed in his small darkroom.[5] For the next two years she was his exclusive model.

In mid-1935 Weston moved to Los Angeles for a project funded by the Works Progress Administration, and he asked Wilson to live with him there. His youngest sons, Neil and Cole, alternately lived with them and with their mother. His older sons, Brett and Chandler (who were also a few years older than Wilson), had opened a photography studio in the area, and Weston used it as a base of operations for his project.

During this same period Weston switched from a 4 X 5 camera to an 8 X 10 view camera.[6] Using the larger camera he made a series of nudes of Wilson, beginning with an iconic study of her in the doorway of their home (Nude (Charis, Santa Monica)). Later, he made his most graphic photos of her at Oceano Dunes, which was then an isolated area of massive sand dunes. Wilson said she found the place "magical" and had no trouble shedding any last semblances of inhibition that might have remained. She recalled that Weston was concentrating on photographing the landscape, when she took off her clothes and rolled down the sand dunes. He immediately focused his camera on her, capturing both the spontaneity of her freedom and her unabashedly sensual form.[1] These photos, which are some of Weston's most recognized images, "mark the climax of Weston's quest for a modern figurative style."[5]

In 1937 Weston applied for and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, the first ever award to a photographer. Wilson authored the application, a four-page narrative, signed by Weston.[7] The Fellowship provided a stipend of $2,000, and with it they began traveling around the West. Together they traveled 16,697 miles in 187 days.

At the end of the year Weston finally divorced his wife, Flora, after 16 years of separation.

The following year the Guggenheim Fellowship was renewed, and Weston and Wilson settled down to printing and cataloging much of his work. They moved to a new home on Wildcat Hill near Carmel, where in a separate building Wilson finally had a place of her own to write. She began a narrative of her travels with Weston, which was published the next year as Seeing California with Edward Weston.

On April 24, 1939, Wilson and Weston were married in Elk, California. Soon after she began writing the text for their next and perhaps most famous book, California and the West, which was published in 1940. In 1941 Weston was asked to take photos for a new edition of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. Once again Wilson and Weston traveled around the country while he took photographs for the Whitman book.

During this trip Wilson and Weston began to drift apart. He continued to be fascinated with younger women and he devoted more and more time to his photography at the expense of their relationship. Wilson, in turn, was growing tired of putting his interests first. She wanted to write more, and she wanted to connect with other people.

She became involved in documenting labor struggles in Northern California, and during her research she met a labor activist named Noel Harris. The two became romantically involved, and Wilson decided it was finally time to break from Weston. On December 13, 1946, she filed divorce papers. Weston waived his right to object, and he casually wrote to Beaumont Newhall, "Charis is in Reno getting a divorce. Cole in L.A. getting new Chevrolet."[1]

Later life

Just one day after her divorce from Weston was finalized, Wilson married Harris. They had two daughters, one of whom, Anita, was murdered in Scotland in 1967.[8] That same year Harris and Wilson divorced. She moved to Santa Cruz and lived close to her other daughter Rachel Fern Harris for the rest of her life.

After the separation from Weston, Wilson was occupied among others as a union secretary and creative writing teacher.[9] In 1977 Wilson wrote the introduction for a book of photographs, Edward Weston Nudes, which is now sought after by collectors. In 2007 she was the subject of a documentary, Eloquent Nude. Her memoir, Through Another Lens, written with Wendy Madar, was published in 1999.

At the time of her death she and her daughter, Rachel, were staying at the home of poet Joseph Stroud in Santa Cruz, California.[10]

Wilson's archive can be accessed at the Center for Creative Photography located on the University of Arizona campus in Tucson.

References

- Wilson, Charis; Wendy Madar (1998). Through Another Lens: My Life with Edward Weston. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 17–55. ISBN 0-86547-521-0.

- "Smithsonian Archives of American Art: Charis Wilson interview, 1982 Mar. 24". Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- Weston, Edward (1972). The Daybooks of Edward Weston. 2. Millerton,NY: Aperture. p. 283.

- Wilson, Charis (1977). Edward Weston Nudes. Millerton, NY: Aperture. pp. introduction. ISBN 0-89381-020-7.

- Stebbins Jr., Theodore E. (1989). Weston's Westons: Portraits and Nudes. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 0-8212-2142-6.

- Richard J. Rinehart. "Edward Weston: A Detailed Chronology". Archived from the original on 2009-11-28. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- Arthur Ollman. "Museum of Photographic Arts. The Model Wife: Excerpts from the book The Model Wife by Arthur Ollman". Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- "Man convicted of killing coed". The Bulletin. 22 February 1968 – via Google Newspapers.

- Weber, Bruce (24 November 2009). "Charis Wilson, Model and Muse, Dies at 95". The New York Times.

- Baine, Wallace (25 November 2009). "The woman in the picture: Beyond her fame as Edward Weston's nude model, Charis Wilson lived a full, three-dimensional life". Santa Cruz Sentinel.

External links

- The Eloquent Nude: The Love and Legacy of Edward Weston and Charis Wilson. Documentary,2007. Directed by Ian McCluskey.

- Weston Family History – Charis Wilson Weston. Photos of Charis Wilson from the Weston family archives.