Margrethe Mather

Margrethe Mather (4 March 1886 – 25 December 1952) was an American photographer. She was one of the best known female photographers of the early 20th century. Initially she influenced and was influenced by Edward Weston while working in the pictorial style, but she independently developed a strong eye for patterns and design that transformed some of her photographs into modernist abstract art. She lived a mostly uncompromising lifestyle in Los Angeles that alternated between her photography and the creative Hollywood community of the 1920s and 1930s. In later life she abandoned photography, and she died unrecognized for her photographic accomplishments.

Margrethe Mather | |

|---|---|

Mather posing for Edward Weston's Carlota (1914) | |

| Born | March 4, 1886 Salt Lake City, Utah, US |

| Died | December 25, 1952 (aged 66) Los Angeles, California, US |

| Known for | Photography |

Life and career

Mather was born in Salt Lake City, Utah the second of four children born to Gabriel Lundberg Youngreen and Ane Sofie Laurentzen. Her parents were Danish immigrants who had been converted to the Mormon faith by a missionary in Denmark. Her mother died while giving birth to the fourth child in 1889[1]

When she was born, Mather was named Emma Caroline Youngreen.[2] After her mother died she was sent to live in another part of town with her maternal aunt, Rasmine Laurentzen. Laurentzen was the live-in housekeeper for local judge Joseph Cole Mather, and the then Emma Caroline was listed in census records as either a "boarder" or "student".[3] In 1906 Mather moved to San Francisco, perhaps in response to calls for aid after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Within two years after moving she changed her name, assuming the last name of her former landlord and the first name of her maternal grandmother, Margrethe Laurentzen. She never explained the reason for her name change to anyone, although photography historian Beth Gates Warren speculated that it might have been due to distancing herself from an affair with a physician that began in Salt Lake City.[4]

In 1912 Mather moved to Los Angeles, where, according to her friend Billy Justema, she made a living primarily as a prostitute for several years.[5] Soon after moving there she joined the Los Angeles Camera Club and also became involved with a circle of self-styled anarchists who were followers of Emma Goldman. Within a year she was part of a growing Bohemian movement in the city that included actors, artists, writers and advocates for social and political change. Her interest in photography quickly blossomed, and by the following year at least one of her photographs had been exhibited in camera club salons in both America and Europe.[6]

She met photographer Edward Weston in the autumn of 1913 when she went to his studio in nearby Tropico. Mather and Weston found they had many of the same photographic interests, and by both Weston's and Mather's accounts the two became intensely involved with each other within six months after they met. At the time, Mather was described as "maddening to the eye, the heart and whatever might be left of reason...distinctly marvelous and infuriating as an individual."[7]

Soon after they met Mather proposed that Weston, she and a small circle of friends that included Fred R. Archer form a new camera club, the Camera Pictorialists of Los Angeles. The club eventually became very influential, but Mather and Weston dropped out after only a year.[8] By that time Weston had begun to receive widespread national and international acclaim, and Mather's relationship with him became more intense as his fame grew.

In 1916 Mather moved to a boarding house in the Bunker Hill neighborhood, where she was said to become involved with a woman referred to only as "Beau"[9] Justema believes "Beau" was Mather's lover and patron, to the extent that soon after the two met Mather opened her first professional photography studio.[10] Although Mather's earliest known photograph dates from 1913, until she opened her studio there is very little record of her photographic output.

During her early years Mather worked in the pictorialist style. One of the first images she created after opening her studio was a soft-focus portrait, Miss Maud Emily, which was later published in Photograms of the Year. She also undertook a series of portraits for the avant-garde magazine The Little Review, including poet Alfred Kreymborg and heiress Aline Barnsdall. Her involvement with the Bohemian circle in Los Angeles also expanded, and through these connections she became friends a growing circle of celebrities and intellectuals like Charlie Chaplin, Max Eastman and Florence Deshon.

By 1918 she was working regularly with Weston, and the two exchanged both stylistic ideas and photographic techniques. That same year she completed a series of portraits of the Chinese poet Moon Kwan that utilized strong shadows as artistic elements. Weston had first experimented with shadows as a dramatic design element in his portrait of Eugene Hutchinson in 1916, but Mather formalized this approach into a continuing stylistic element in her portraits for many years after that. This style was so unusual at the time that one critic wrote "The appreciation of this form of composition…is at present with the writer purely an intellectual one, like that of some of the newer forms in music and painting. Presumably the next generation will accept arrangements like this instinctively. Such is the way in which art grows."[11]

In 1921 Mather's and Weston's joint photographic interests reached the point that they entered into a semi-formal partnership. For most of that year they created a series of about a dozen photographs that they jointly signed – the only time in Weston's career that he was known to have shared credit with another photographer[12] One reviewer referred to the two photographers as an "art partnership," although there are some indications that Mather might have taken at least some of the photos on her own and signed both names on the prints[12] During this same period she made several stunning portraits of Weston, including full-frame close-ups that capture his somewhat soulful expression.

The next year marked the beginning of an artistic style change for both Mather and Weston. There is no direct indication of who influenced whom, but photographer Imogen Cunningham, who knew both Weston and Mather well, said that in artistic matters, Mather was the teacher and Weston was the pupil[13] Both moved rather quickly away from the pictorial style and started to make more sharply focused photographs with bolder lines and angles. Her work from this period reflected a "daring, confident and sophisticated understanding of space"[14] that few others working at the same time ever achieved.

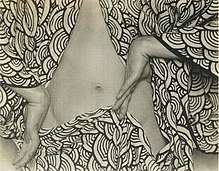

In 1923 Weston became infatuated with photographer Tina Modotti and decided to travel to Mexico with her. Before he left he took a series of nude studies of Mather in the sand dunes at Redondo Beach, California. These images that bear a close resemblance to his more famous nudes of his second wife Charis Wilson taken 13 years later. After Weston left, Mather immediately expanded her career with a new group of portraits of famous artists, musicians and writers, including Pablo Casals, Rebecca West, Eva Gauthier, Ramon Novarro, Konrad Bercovici, and Richard Buhlig. Her portraits were said to appear "deceptively simple, made with a great economy of detail…[but also with] great sensitivity and precision [that] cuts through to the essence of the subject."[14]

It was during this same period that she became close friends with and repeatedly photographed the budding artist Billy Justema. Justema was nearly 20 years younger than Mather, and they formed a mutually beneficial and platonic relationship that lasted many years. Justema said that Mather "would nurture and shield me, thoroughly and unwittingly corrupt me, and…set up standards of ethical behavior and artistic excellence,"[15] while Mather thrived on the new and changing circle of talented musicians and artists that Justema brought to her home. One of her most famous images, Semi-Nude, a strong horizontal image of Justema's abdomen and contorted hands wrapped loosely by a boldly patterned kimono, was made soon after the two met. This is the earliest example of a strong decorative element in Mather's work, and she would use this stylistic device repeatedly as she continued to develop for own artistic vision.

Mather and Justema jointly applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1928 for a proposal they called "The Exposé of Form". In the application they described photographs they had been working on together, with Mather as the photographer and Justema the designer, that included images of hands, eggs, melons, waves, bathroom fixtures and seashells. Later Weston would also explore these same subjects. The application was not approved, and for the next two years Mather's interest in photography declined.

In 1930 Justema moved to San Francisco and through his connections was able to secure a one-person exhibition for Mather at the M.H. De Young Memorial Museum. She mounted a collection of significant new photos for the exhibition, based on a theme of strong patterns made up of repeated combinations of common objects like combs, fans, shells, clocks and chains. One of her more provocative images from this series was a collection of glass eyes, laid out in a neat rows and each staring in a slightly different direction. When the exhibition opened, one reviewer referred to her (although erroneously) as "Margrethe Mather, San Francisco modernist."[16]

After the exhibition Mather returned to Los Angeles and developed a long-lasting relationship with George Lipton, described as "a garrulous, hard-drinking man" she first met back in the early anarchist days. Lipton ran an antiques shop, and Mather worked part-time for him while pursuing her photography. Her health gradually declined over the next decade, and her interest in photography faded at the same time. In the early 1940s she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, an affliction that at that time was highly debilitating and degenerative. By then she and Lipton had developed a mutually caring relationship, although the true extent of it was never disclosed.

Mather died on Christmas Day 1952. The official death record stated her name as "Margaret Lipton" and her occupation as "housewife," two identities she never actually claimed or would have liked.[17] By that time Weston had destroyed most of his journals and notes from his early days in Los Angeles, and he mentioned her only briefly in his extensive published journal Daybooks. For the two decades between 1915 and 1935, however, she was one of the best known female photographers in America.

References

- Warren 2011, 19

- Warren 2001, 12

- Warren 2011, 23

- Warren 2011, 25

- Justema, 6–7

- Warren 2001, 10

- Nancy Newhall, quoted in Warren 2011, 56–57

- Wilson, 69

- Warren 2001, 16

- Justema, 8

- Frank Roy Fraprie, quoted in Warren 2001, 22

- Warren 2001, 28

- Justema, 9

- Jasud, 58

- "Margrethe Mather: Photographer". Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- Warren 2001, 36

- Warren 2001, 37

Sources

- Jasud, Lawrence. "Margrethe Mather: Questions of Influence." Center for Creative Photography, no 11, 1979, pp 54–59

- Justema, William. "Margaret: A Memoir." Center for Creative Photography, no 11, 1979, pp 5–19

- Warren, Beth Gates. Artful Lives: Edward Weston, Margrethe Mather, and the Bohemians of Los Angeles. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011 ISBN 978-1-60606-0704

- Warren, Beth Gates. Margrethe Mather & Edward Weston: A Passionate Collaboration. NY: Norton, 2001 ISBN 0-393-04157-3

- Wilson, Michael G. and Dennis Reed. Pictorialism in California, Photographs 1900–1940. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1994. ISBN 0-89236-312-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Margrethe Mather. |