Ecgric of East Anglia

Ecgric (killed circa 636) was a king of East Anglia, the independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom that today includes the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. He was a member of the ruling Wuffingas dynasty, but his relationship with other known members of the dynasty is not known with any certainty. Anna of East Anglia may have been his brother, or his cousin. It has also been suggested that he was identical with Æthelric, who married Hereswith and was the father of Ealdwulf of East Anglia. The primary source for the little that is known about Ecgric's life is Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum.

| Ecgric | |

|---|---|

| King of the East Angles | |

| Reign | circa (c.) 630 – c. 636 (jointly with Sigeberht until c. 634) |

| Predecessor | possibly Ricberht of East Anglia |

| Successor | Anna of East Anglia |

| Died | killed in battle c. 636 |

| Dynasty | Wuffingas |

| Religion | Anglo-Saxon Paganism |

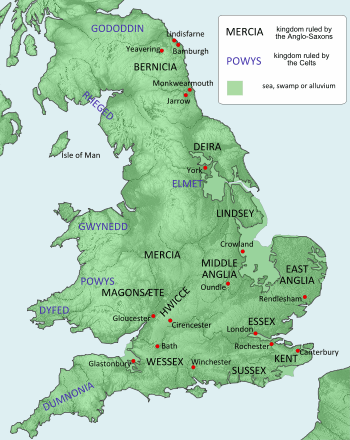

In the years that followed the reign of Rædwald and the murder of Rædwald's son (and successor) Eorpwald in around 627, East Anglia lost its dominance over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Three years after Eorpwald's murder at the hands of a pagan, Ecgric's kinsman Sigeberht returned from exile and they ruled the East Anglians together, with Ecgric perhaps ruling the northern part of the kingdom. Sigeberht succeeded in re-establishing Christianity throughout East Anglia, but Ecgric may have remained a pagan, as Bede praises only Sigeberht for his accomplishments, and his lack of praise for his co-ruler is significant. Ecgric ruled alone after Sigeberht retired to his monastery at Beodricesworth in around 634: it has also been suggested that he was a sub-king who only became king after Sigeberht's abdication. Both Ecgric and Sigeberht were killed in battle in around 636, at an unknown location, when the East Anglians were forced to defend themselves from a Mercian military assault led by their king, Penda. Ecgric, whose grave may have been the ship burial under Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo, was succeeded by Anna.

East Anglian allegiances

After 616, Rædwald, who ruled East Anglia during the first quarter of the seventh century, was the most powerful of the southern Anglo-Saxon kings.[1] In the following decades, from the reign of Sigeberht onwards, East Anglia became increasingly dominated by Mercia. Raedwald's son Eorpwald was murdered by a pagan noble soon after he was baptised in around 627, after which East Anglia reverted into paganism for three years.[2] In the void left by the death of Rædwald, the first overlord who originated north of the Thames, the pagan Penda of Mercia emerged to challenge the pre-eminence of the new overlord (or bretwalda), Edwin of Northumbria.[3] The reversion of East Anglia to rule by Eorpwald's successor, the pagan Ricberht, possibly due to Mercian influence, temporarily overthrew an important pillar of Edwin's authority.[4]

In contrast, two sons of Rædwald's brother Eni, who were both eager to renew their Christian alliances, made diplomatic marriages during this period: Anna, who was to become a devout Christian ruler, married a woman of East Saxon connection and his brother Æthelric married a Northumbrian princess, Hereswitha, who was Edwin of Northumbria's grand-niece. This marriage was probably intended to reinforce the conversion of East Anglia to Christianity.[5]

Wuffingas identity

Ecgric was a member of the Wuffingas royal family, but his exact descent is not known, as the only information historians have is from Bede, who named him as Sigeberht's cognatus or 'kinsman'.[6] The 12th century English historian William of Malmesbury contradicts Bede, stating that Sigeberht was Rædwald's stepson. The name Sigeberht is not of East Anglian, but of Frankish origin.[7] Rædwald may have exiled his step-son so as to protect the inheritance of his son Ecgric, who was of his own blood-line.[8]

It has been suggested by Sam Newton that Ecgric may in fact be identical to Eni's son Æthelric, whose descendants became kings of East Anglia.[9] Æthelric's son Ealdwulf ruled from about 664 to 713. After Ecgric's death, three other sons of Eni ruled in succession before Ealdwulf, an indication that Raedwald's line was extinct. Æthelric's marriage to Hereswith suggests that it was expected that he would rule East Anglia and he may have been promoted by Edwin before 632.[5] Æthelric was apparently dead by 647, at which time Anna was already ruling and Hereswith had gone to Gaul to lead a religious life.[10] It has therefore been argued that Æthelric and Ecgric were in fact the same person, a suggestion that is disputed by the historian Barbara Yorke, who notes that the two names are too distinct to be compatible.[11]

Ecgric/Æthelric placed as the son of Rædwald or the son of Eni

| Tytila | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ? | Rædwald | ? | Eni | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rægenhere | Eorpwald | Ecgric | Sigeberht | Ecgric | Anna | Æthelhere | Æthelwold | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Joint rule

Rædwald's son (or stepson) Sigeberht renewed Christian rule in East Anglia after returning as a Christian from exile in Gaul (into which Rædwald had driven him). His assumption of power may have involved a military conquest.[5] His reign was devoted to the conversion of his people, the establishment of the see of Dommoc as the bishopric of Felix of Burgundy, the creation of a school of letters, the endowment of a monastery for Fursey and the building of the first monastery of Beodricesworth (Bury St Edmunds), all accomplished within about four years.[12]

During at least part of Sigeberht's reign, Ecgric ruled jointly with him over part of the kingdom of East Anglia.[13] A passage in Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum describing the reasons for Sigeberht's abdication also mentions Ecgric:

- "This king became so great a lover of the heavenly kingdom, that quitting the affairs of his crown, and committing the same to his kinsman, Ecgric, who before held a part of that kingdom, he went himself into a monastery, which he had built, and having received the tonsure, applied himself rather to gain a heavenly throne":

- —Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People[13]

According to Richard Hoggett, the practice of being ruled by more than one individual may have been a common occurrence in East Anglia as it was for the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Kent and Northumbria. Ecgric and Sigeberht may have simultaneously ruled the peoples known as the North-folk and South-folk, who lived in the parts of their kingdom that would later become the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk.[14] However, Carver notes that Ecgric may not have reigned jointly with Sigeberht, but could just have plausibly ruled as a sub-king or served as an administrator within a region under East Anglian hegemony, only rising as king of the East Angles after Sigeberht's abdication.[15]

In contrast with Sigebert, Ecgric seems to have remained a pagan. There is no evidence that he was baptised or that he promoted Christianity in East Anglia, according to D. P. Kirby, who notes that Bede wrote nothing that could imply that Ecgric was a Christian, in contrast to his praise of Sigeberht’s efforts to establish Christianity in East Anglia.[16]

Reign following Sigeberht's abdication

In 633 the Christian kingdoms suffered a dual shock: Edwin of Northumbria's death at the hands of Penda of Mercia and Cadwallon ap Cadfan, and the retreat of Edwin's household and bishop from York to Kent.[17] After 633 the Northumbrian situation was stabilised under Oswald of Northumbria, and East Anglia shared with Northumbria the benefits of the Irish missions of Fursey and Aidan of Lindisfarne. Sigeberht was Fursey's patron and perhaps soon after his arrival Sigeberht abdicated and retired to the monastery at Beodricesworth (modern Bury St. Edmunds). His abdication, which cannot be dated, left Ecgric to rule the East Anglians alone.[18] Ecgric therefore ruled a kingdom that had been "evangelised in the united spirit of the Roman and Irish Churches", according to Plunkett, who notes that Felix would have respected the teachings of the Irish missionaries, despite his own strong allegiance towards Canterbury.[19]

Death

After Ecgric had been ruling alone for two years, East Anglia was attacked by a Mercian army, led by Penda. The date of the invasion is usually given as around 636, although Kirby suggests it could have been so late as 641.[20] Ecgric was sufficiently forewarned as to be able to gather an army, described by Bede as opimus or splendid.[21] Realising that they would be inferior in battle to the war-hardened Mercians and remembering that Sigeberht was once their most vigorous and distinguished leader, the East Anglians urged him to lead them in battle, hoping that his presence would encourage them not to flee from the Mercians. After he refused, on account of his religious calling, he was borne off against his will to the battlefield. He refused to bear weapons and so was killed.[14] Ecgric was also slain during the battle and many of his countrymen either perished or were put to flight. The location of the site of the battle in which the East Anglians were routed and their king was killed is unknown, but it can be presumed to have been close to the kingdom’s western border with the Middle Angles.[14]

Ecgric is a possible contender, as well as Rædwald, Eorpwald and Sigeberht, for being the East Anglian king who was buried within Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo.[22] Rupert Bruce-Mitford suggests that it is perhaps unlikely that Ecgric’s successor Anna, a devout Christian, would have given him a ship burial, but he does not dismiss the theory entirely.[23]

Footnotes

- Hoggett, The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion, pp. 28, 29.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 62.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 55

- Plunkett, Suffolk, pp. 97–99.

- Plunkett, Suffolk, p. 100.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 69.

- According to Bede, Sigeberht was Rædwald's son. Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 62, 65, 67.

- Plunkett, Suffolk, p. 72.

- Hoggett, The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion, p. 25.

- Hunter Blair, in Lapidge and Gneuss, Learning and Literature in Anglo-Saxon England, p. 6.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 68.

- Plunkett, Suffolk, pp. 100–1, 106.

- Ecclesiastical History, Book III, Chapter 18.

- Hoggett, The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion, p. 32.

- Carver, The Age of Sutton Hoo, p. 6.

- Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 67.

- Lapidge, The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 164.

- McClure and Collins, in Bede, Ecclesiastical History, p. 392, note 138.

- Plunkett, Suffolk, p. 105.

- Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, p. 74.

- Plunkett, Suffolk, p. 106.

- Bruce-Mitford, The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, pp. 63, 99.

- Bruce-Mitford, The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, p. 101.

References

- The Venerable Bede; Ed. B. Colgrave and R.A.B. Mynors (1969). Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum. Oxford.

- Bede (1999). McClure, Judith; Collins, Roger (eds.). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283866-0.

- R.L.S. Bruce-Mitford (1975). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial, Vol. 1. London: British Museum.

- Carver, M. O. H. (2006). The age of Sutton Hoo: the seventh century in north-western Europe. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-330-5.

- Dumville, D.N. (1976), "The Anglian Collection of Royal Genealogies and Regnal Lists", Anglo-Saxon England, University of Cambridge, 5 (23–50)

- D.H. Farmer (1978). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-282038-9.

- Hoggett, Richard (2010). The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-84383-595-0.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1985). "Whitby as a centre of learning in the seventh century". In Michael Lapidge and Helmut Gneuss (ed.). Learning and Literature in Anglo-Saxon England: Studies Presented to Peter Clemoes on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25902-9.

- D. P. Kirby (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 67, 74. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Lapidge, Michael (2001). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- J. Morris (1980). Nennius: British History and The Welsh Annals. London and Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-298-2.

- S. Plunkett (2005). Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3139-0.

- A. Williams; A.P. Smyth; D.P. Kirkby (1991). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. Seaby. ISBN 1-85264-047-2.

- B. Yorke (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of early Anglo-Saxon England. London. ISBN 1-85264-027-8.

External links

| English royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ricberht |

King of East Anglia

with Sigeberht until c. 634 |

Succeeded by Anna |