Drosera falconeri

Drosera falconeri is a carnivorous plant in the genus Drosera. It is endemic to the Northern Territory of Australia.

| Drosera falconeri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Droseraceae |

| Genus: | Drosera |

| Subgenus: | Drosera subg. Lasiocephala |

| Species: | D. falconeri |

| Binomial name | |

| Drosera falconeri | |

| |

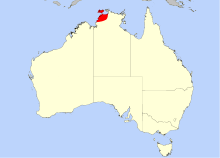

| Distribution of D. falconeri in Australia | |

Description

Drosera falconeri superficially resembles the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula).[2][3] In a review of the research on the evolution of the Venus flytrap from sticky-leaved ancestors, botanists Thomas Gibson and Donald Waller use D. falconeri as an example of a sticky-leaved species that shares many characteristics with the Venus flytrap, such as a wide petiole and lamina, and faces the same challenge of prey escape that the snap trap of the Venus flytrap evolved in response to.[3]

Drosera falconeri is a tropical perennial plant with a rosette body plan that is common for the genus Drosera. Deciduous leaves lay flat against the soil. Leaves are usually smaller at anthesis (flowering), but increase as the growing season progresses.[4] Typical reniform lamina at maturity are 1.5 cm (0.6 in) long and 2 cm (0.8 in) wide,[4] with leaves on older specimens being as wide as 3 cm (1.2 in).[5] It is unique in the subgenus because of its large leaves that are typically flat against the soil.[5] Retentive mucilage-producing glands held on stalks – structures known as tentacles – appear on the margin of the lamina with shorter glands in the center of the leaf. The abaxial (underside) surface of the leaf is noticeably veined and sparsely covered with non-glandular white hairs. Petioles are oblanceolate and usually 10 mm long with varying widths: 2 mm near the center of the rosette, 3.5 mm near the center of the petiole, and 3 mm at the point of attachment to the lamina. The upper surface of the petiole is glabrous, but the margins and lower surface possess hairs similar to those of the abaxial leaf surface.[4]

One or two racemose inflorescences are produced per plant and are usually 8 cm (3.1 in) long. Approximately 12 flowers are found on one inflorescence with each white or pink flower held on a 3–5 mm long pedicel. The scape, inflorescence, and sepals are sparsely covered in white hairs. Flowers are composed of elliptic 3 mm long by 1.8 mm wide sepals, 7 mm long by 4 mm wide petals, five 2.7 mm long white stamens that produce orange anthers and pollen, a 1.1 mm diameter ovary with bilobed carpels and three white 2.5 mm long styles that are extensively branched toward the apex with terminal white stigmas. It typically flowers from November to December with only one flower open at a time, lasting for just one day whether it was pollinated or not.[4]

In the dry season the leaves die back and the plant survives by forming a bulb-like structure of tightly-packed leaf bases just below the soil's surface. This adaptation helps it avoid desiccation during the dry season. The hard clay soils acts as insulation; all other species in subgenus Lasiocephala use dense white hairs for insulation. Dormancy is typically broken with the first rains of the wet season and growth proceeds quickly. New growth, such as a new fibrous root system, new leaves, and the inflorescence, must build up reserves and set seed; a short wet season and sudden drought may cut the growing season considerably. New roots are white and fleshy, mostly serving as a water storage organ, while older roots become thinner and mostly anchor the plant.[4]

Hybrids

It can readily hybridise with other species in the D. petiolaris complex, which includes the species in the subgenus Lasiocephala.[7] Hybridisation is rare in the wild, however, because the soil types specific to individual parent species do not converge often. The first natural hybrid to be discovered was the product of D. falconeri and D. dilatato-petiolaris,[4] later given the nomen nudum D. dilaconeri in 1991 by E. Westphal.[1] Seed from this hybrid has proved to be viable which is an unusual characteristic for Drosera hybrids.[4] Approximately four recognisable forms of this hybrid can be found in the wild. The characteristics favour one parent species or the other: some forms are smaller at 4–5 cm (1.6–2.0 in) in diameter while others can be up to 10 cm (3.9 in) in diameter, the leaf varies in size, and some hybrids will form clumps by producing plantlets like D. dilatato-petiolaris does while others will remain isolated.[5] Drosera falconeri also hybridises with D. petiolaris; this hybrid was given the nomen nudum D. petioconeri by Westphal in 1991.[1]

Artificial hybrids involving D. falconeri have also been produced and cultivated, including a complex hybrid: (D. falconeri × D. ordensis) × (D. darwinensis × D. falconeri).[8]

Distribution and ecology

Drosera falconeri is common throughout the northern coastal areas of the Northern Territory in Australia. It was originally located along the Finniss River in alkaline sandy soils.[5][9] It is found growing in the grey silty clay soils in the Palmerston and Berry Springs regions and on Melville Island.[4]

While most carnivorous plants are calcifuges that cannot tolerate alkaline soils, D. falconeri grows on calcareous sandy soils with high pH values.[10][11] In the first account of this species' habitat, the soil pH at the site was recorded as pH 8.[12] At the site where D. falconeri was first discovered, tall dense grass covered the small population.[12]

Botanical history and taxonomy

Drosera falconeri was first discovered by a Mr Falconer in 1980 along the Finniss River in the Northern Territory. Falconer was collecting plants and tropical fish for Peter Tsang, a carnivorous plant enthusiast living in Queensland. Tsang then sent specimens on to Allen Lowrie and Bill Lavarack, a botanist with the Queensland National Parks. Tsang also prepared a short announcement of this new species published in the June 1980 issue of the Carnivorous Plant Newsletter, giving a brief description and suggesting the specific epithet honour Mr Falconer as its discoverer. It was not until 1984 that Katsuhiko Kondo provided the formal description required under the rules of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature in an article that described three new species in the D. petiolaris complex.[5][12] The holotype specimen is Kondo 2227 held at the Herbarium of Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Hiroshima University. Isotype specimens, those that are duplicates of the holotype, were distributed to several herbaria, including those at the University of North Carolina, the New York Botanical Garden, the National Herbarium of New South Wales, and the Queensland Herbarium.[13][14]

The species was only known from a single location, the description of which vaguely positioned it along the Finniss River, a river that is nearly 100 km (60 mi) long. Tsang died in 1984 and it was feared that the exact location of the known population was lost with him. Further field studies, however, produced several new sites.[5]

Its alliance with the D. petiolaris complex in subgenus Lasiocephala was suspected from its earliest description by Peter Tsang, who noted similarities in their dormant bud and root structures.[12] This assessment has been confirmed by further analysis by other botanists.[4]

Cultivation

Drosera falconeri was first cultivated by Peter Tsang shortly after its initial discovery. He then sent living specimens on to others to establish the new species in cultivation.[5][12]

It is considered to be a difficult species to grow in cultivation. During its seasonal dormancy, D. falconeri produces a tight rosette of leaves that resembles a hibernating bud. It is often grown in a peat:sand or perlite soil. Plants can be vegetatively propagated by submerging leaf pullings in pure water.[7] Under the Australian botanist Allen Lowrie's growing conditions, species in subgenus Lasiocephala grow year-round without dormancy. Lowrie also notes that these species produce deep red foliage in the wild, a characteristic that is lost in cultivation when plants retain a greener appearance presumably caused by lower light intensities.[5]

References

- Schlauer, J. 2010. World Carnivorous Plant List - Nomenclatural Synopsis of Carnivorous Phanerogamous Plants. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Rice, B. A. 2006. Growing Carnivorous Plants. Timber Press: Portland, Oregon, USA. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-88192-807-5

- Gibson, T. C., and D. M. Waller. 2009. Evolving Darwin's 'most wonderful' plant: ecological steps to a snap-trap. New Phytologist, 183: 575-587. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02935.x

- Lowrie, A. 1998. Carnivorous Plants of Australia, vol. 3. Nedlands, Western Australia: University of Western Australia Press. pp. 168-171.

- Lowrie, A. 1990. The Drosera petiolaris complex. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter, 19(3-4): 65-72.

- Hoshi, Yoshikazu. 2002. Chromosome studies in Drosera (Droseraceae). Proceedings of the 4th International Carnivorous Plant Conference. pp. 31-38.

- Rice, B. 2008. The "petiolaris-complex." The Carnivorous Plant FAQ. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Rivadavia, F. 2009. Drosera × fontinalis (Droseraceae), the first natural sundew hybrid from South America. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter, 38(4): 121-125.

- D'Amato, P. 1998. The Savage Garden: Cultivating Carnivorous Plants. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, California. p. 146. ISBN 0-89815-915-6

- Adlassnig, W., M. Peroutka, H. Lambers, and I. K. Lichtscheidl. 2005. The roots of carnivorous plants. Plant and Soil, 274: 127-140. doi:10.1007/s11104-004-2754-2

- Juniper, B. E., R. J. Robins, and D. M. Joel. 1989. The Carnivorous Plants. London: Academic Press Limited. p. 23. ISBN 0-12-392170-8

- Tsang, P. 1980. A new Drosera from the top end of Australia. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter, 9(2): 46 & 48.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew https://www.ipni.org/n/165959-3. Retrieved 14 March 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Drosera falconeri". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

External links

![]()