Dresden Hauptbahnhof

Dresden Hauptbahnhof (“main station”, abbreviated Dresden Hbf) is the largest passenger station in the Saxon capital of Dresden. In 1898, it replaced the Böhmischen Bahnhof ("Bohemian station") of the former Saxon-Bohemian State Railway (Sächsisch-Böhmische Staatseisenbahn), and was designed with its formal layout as the central station of the city. The combination of a station building on an island between the tracks and a terminal station on two different levels is unique. The building is notable for its halls that are roofed with Teflon-coated glass fibre membranes. This translucent roof design, installed during the comprehensive rehabilitation of the station at the beginning of the 21st century, allows more daylight to reach the concourses than was previously possible.

| Junction station | |

Aerial view of Dresden Hauptbahnhof (2006) | |

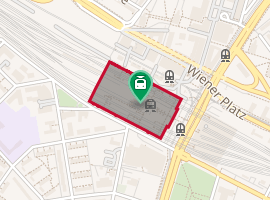

| Location | Wiener Platz 4, Seevorstadt, Dresden, Saxony Germany |

| Coordinates | 51°02′25″N 13°43′54″E |

| Line(s) | |

| Platforms | 16 |

| Construction | |

| Architect |

|

| Architectural style | Historicism and modernism |

| Other information | |

| Station code | 1343 |

| DS100 code | DH[1] |

| IBNR | 8010085 |

| Category | 1[2] |

| Website | www.bahnhof.de |

| History | |

| Opened | 23 April 1898 |

| Traffic | |

| Passengers | 60,000 (daily) |

| |

| Location | |

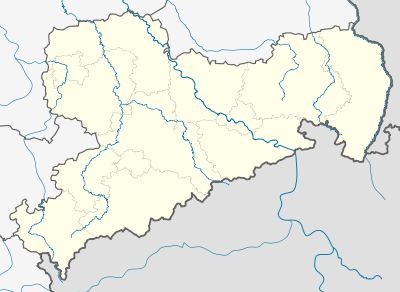

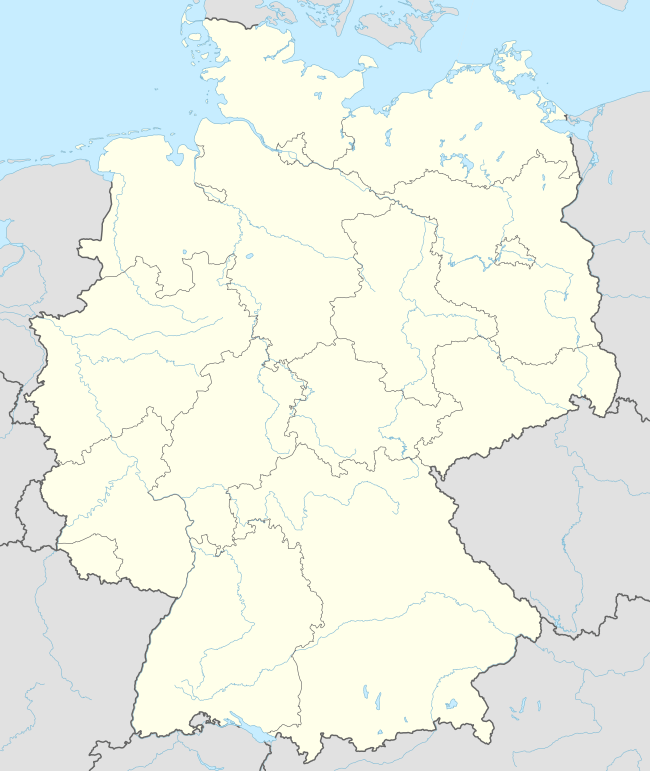

Dresden Hauptbahnhof Location within Saxony  Dresden Hauptbahnhof Location within Germany  Dresden Hauptbahnhof Location within Europe | |

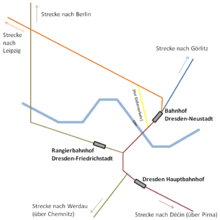

The station is connected by the Dresden railway node to the tracks of the Děčín–Dresden-Neustadt railway and the Dresden–Werdau railway (Saxon-Franconian trunk line), allowing traffic to run to the southeast towards Prague, Vienna and on to south-eastern Europe or to the southwest towards Chemnitz and Nuremberg. The connection of the routes to the north (Berlin), northwest (Leipzig) and east (Görlitz) does not take place at the station, but north of Dresden-Neustadt station (at least for passenger trains).

Location

The station is located south of the Inner Old Town in the Seevorstadt and the district of Südvorstadtat reaches its southern edge. Right next to the station area is the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Dresden (University of Applied Sciences). Federal highway 170 passes under the station area to the east of the station building, running north-south.

Prager Straße, the inner-city shopping street, begins at Wiener Platz to the north. Road traffic on Wiener Platz was diverted in the 1990s to run through a road tunnel with connections to underground parking, and it is now a pedestrianised street. Several major buildings have been constructed in the area in the modern style and there is an excavation in Wiener Platz, which was dug a few years ago, but construction has been abandoned (2013).

History

In 1839, the Leipzig–Dresden Railway Company (Leipzig-Dresdner Eisenbahn-Compagnie) opened the first long-distance railway in Germany from Leipzig to its Dresden terminus, the Leipziger Bahnhof. In the following decades more railways were built, increasing the destinations that could be reached from Dresden. Each private company built its own station as the terminus of its lines. The Silesian Station (Schlesischer Bahnhof) was opened in 1847 as the terminus of the Görlitz–Dresden railway and the Bohemian station (Böhmische Bahnhof) was opened in 1848 on the line towards Bohemia. Seven years later, the Albert station (Albertbahnhof) was opened on the line towards Chemnitz and the Berliner station (Berliner Bahnhof) opened in 1875 on the line to Berlin.

Between 1800 and 1900, the population of Dresden grew from 61,794 to 396,146. As a result, traffic grew enormously. The existing railway facilities proved to be inadequate to satisfy the increasing traffic as a result of rising mobility, population increase and industrialisation. In particular, the railway tracks of the poorly interconnected stations were not designed for through traffic and the many level crossings created major traffic problems.

After the late 1880s, when all the railway infrastructure affecting the city had been nationalised, the Saxon government decided to carry out a fundamental reconstruction of the Dresden railway node under the leadership of the engineer Otto Klette. This would create a new central railway station, but there was no consensus on its location for a long time. After the Elbe flood of March 1845, the inspector of surveys, Karl Pressler suggested that the Weißeritz near Cotta should be relocated and that the existing riverbed could be used for a central station. This plan was taken up and the former riverbed was used for a connection line between Dresden's long-distance railway stations, but, instead of a central station, the planners foresaw a new main station in front of the former Bohemian station, as it was already the busiest station in Dresden and it was close to Prager Straße, which became the most important shopping street of Dresden in the last quarter of the 19th century.[3]

Böhmischer Bahnhof

On 1 August 1848, the Saxon-Bohemian State Railway (Sächsisch-Böhmische Staatseisenbahn) opened the Bohemian station as the terminus of its line, which only extended to Pirna.[4] It was initially only a barn-like half-timbered building spanning four tracks and it also had a makeshift locomotive depot, carriage sheds and workshops.

.jpg)

The opening ceremony took place on 6 April 1851, coinciding with the extension of the line to Bodenbach (now Děčín).[4] A year later the opening of the Marienbrücke (Maria Bridge) for road and rail traffic on 19 April 1852 allowed the operation of traffic through the Bohemian station to the Leipziger station and the Silesian Station on the Neustadt side of the Elbe.

From 1861 to 1864, the passenger infrastructure was moved to the west, to make room for a new building. On 1 August 1864, a solid new entrance building replaced the previous provisional building [4] Four 184 metre long wings, which were designed by Karl Moritz Haenel and Carl Adolph Canzler in the form of Italian Renaissance buildings, were annexed.The main platform could handle two trains simultaneous at first, but it was only 370 metres long. An additional 360-metre-long island platform was built between 1871 and 1872. This extension had become necessary because in 1869 the Bohemian station took over the passenger traffic of the Dresden–Werdau railway from the Albert Station, which was located about two kilometres to the northwest and subsequently only served coal traffic. In order to handle the traffic towards Chemnitz a new main station (Hauptbahnhof) was built in front of the Bohemian station.[5] In addition, the new Hauptbahnhof would handle the passenger traffic of the Berliner station, which was also located in the Old Town (Altstädt) on the south side of the Elbe, but almost three kilometres to the northwest.

Construction and opening

.jpg)

.jpg)

The basic functional design of the station with the combination of a large terminal hall at a low level and two flanking through halls at a high level is considered to be the work of Claus Koepcke, a ministry of finance official, and Otto Klette.[6] This functional framework was based on an architectural competition held in 1892 for the design of the new station. Dresden architects Ernst Giese and Paul Weidner and Leipzig architect Arwed Roßbach each won a first prize.[7] The realised design incorporates elements of both drafts. Construction began in the same year, led by Ernst Giese and Paul Weidner. Railway operations continued at the Bohemian station while the south hall was opened to traffic on 18 June 1895. Subsequently, the Bohemian station was demolished and the construction of the central and northern halls started on its site. Until the completion of the entire building, the south hall served as the provisional station.[3]

The new building, which had six terminal platform tracks in the central hall, six through high-level tracks and other terminal tracks in the eastern precinct, met all the requirements for greatly expanded passenger operations. A roofed building with two elevated tracks was built for freight traffic between the south hall and Bismarckstraße (now Bayrischen Straße) to the south. The entrance building covered an area of approximately 4,500 square metres. The steel fabrication company, August Klönne supplied 17,000 tons of steel for the structure of the platform halls and the masonry consists of Elbe Sandstone.[8] The cost of construction amounted to 18 million marks; corresponding to the equivalent of about €320 million.[9]

After more than five years of construction the whole building went into operation on 16 April 1898.[10] At 2:08 AM the first train running as the 101 from Leipzig entered the newly opened Dresden Hauptbahnhof.[10]

As a result of the restructuring of the Dresden railway infrastructure that was carried out simultaneously, the station received better links with the lines to Leipzig, Berlin and Görlitz, which had previously been poorly connected. A new high-capacity, continuous four-track urban connecting line was opened through the new Wettiner Straße station (now Dresden Mitte station) for suburban traffic and the Maria Bridge to Dresden-Neustadt station in 1901. It was connected by rail junctions to other stations, in particular to Dresden-Friedrichstadt station.

Although it was built in the heyday of luxury trains, it was almost unaffected by this phenomenon with only one branch of the Balkanzug (Balkan train) serving Dresden between 1916 and 1918.

Early conversions and extensions

The builders of the station assumed that the new facilities would provide sufficient capacity for many decades. In fact, the volume of traffic developed more rapidly than assumed as indicated in the table below.[11]

| Year | Station | Trains starting at station | Trains ending at station | Through trains | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871 | Böhmischer Bahnhof | 13 | 13 | 16 | 42 |

| 1898 | Böhmischer Bahnhof | 208 | |||

| 1898 | Hauptbahnhof | 304 | |||

| 1910 | Hauptbahnhof | 199 | 191 | 14 | 404 |

| 1930 | Hauptbahnhof | 174 | 178 | 63 | 415 |

Since the rapid increase in traffic could barely be handled, the first expansion of facilities was planned prior to the start of the First World War. In 1914, the Saxon Parliament approved funds for the expansion, but the beginning of the war prevented its realisation. The extension could not be started until the late 1920s.[12]

One obstacle to operations until then was that it was difficult to reach the terminal tracks in the eastern precinct. As a remedy, a new through track was built through the north hall between platforms 10 and 11, replacing a luggage platform. This would henceforth be used for the passage of additional trains to the eastern precinct and for the passage of unattached locomotives and freight traffic. To take advantage of the sharp rise in through passenger traffic, the covered side hall next to the south hall was demolished, so that the two freight train tracks could be moved on to an outer track on a new concrete structure over the pavement and the released space could be used for an island platform.[12]

The signal box equipment was modernised at that time. New electromechanical systems replaced the mechanical systems and a new command signal box tower was built on the Hohe Brücke (bridge) that at that time carried an extension of Hohe Straße over the station's western track field. The architecture of the station was also transformed. Numerous decorations and structures were replaced by modern plain surfaces.[12]

During the Third Reich

In the 1930s, Deutsche Reichsbahn began to construct of a high-speed rail network. It operated high-speed diesel multiple units on routes between Berlin and Hamburg, Berlin and Cologne and Berlin and Frankfurt among others. However, the connection from Dresden to Berlin was served by a high-speed steam-hauled train, the Henschel-Wegmann Train. From 1936 until the outbreak of war in 1939, it operated the line from Dresden to the Anhalter Bahnhof in about 100 minutes.

In the late 1930s, the Nazis were planning to reconstruct the city with the intention of glorifying the Third Reich on an enormous scale. A new central train station to be built at Wettiner Straße station would have been 300 metres wide and 200 metres long. In addition, an oversized station courtyard and spacious streets were intended to create spaces for rallies and marches. With the outbreak of the Second World War, however, these plans lapsed.[13]

During the Second World War the station had only minor importance for the dispatch of troop and prisoner transports, though Dresden was a garrison town. However, it connected the Saxon railway network with Bohemia and formed a bottleneck as a result.

At the beginning of the war Dresden hardly seemed threatened by air raids, so initially insufficient preparations were made and later additional preparations were no longer possible. The air raid shelters of the central station could accommodate about 2,000 people, but they lacked airlocks and ventilation systems.[14] This had serious consequences: during the great air raid on the night of 13 and 14 February 1945 the station burned down, and the entrance to the luggage store was set alight; as a result 100 people were burned to death and another 500 people suffocated in the air raid shelters.[15]

Subsequent air raids destroyed the railway tracks entirely. The station was made permanently inoperable during the eighth and final air raids on the city on 17 April 1945 by 580 USAAF bombers.

The long reconstruction

In spite of its severe war damage the station was one of the distinctive buildings in the central Dresden. The restoration of rail connections had to take precedence over the restoration of the historic building. So passenger services were restored to Bad Schandau by 17 May 1945.[16]

A temporary reconstruction began after the war and was completed in the same year. Some parts of the building, such as the concourses and the dome, were not immediately repaired and continued to deteriorate. At the same time a far-reaching reorganisation of the railway infrastructure was considered as the large-scale destruction of the city seemed to make it possible. Draft plans from 1946 show a turning loop south of the station, which would have allowed east-west traffic on the Chemnitz–Görlitz route to stop without a change of locomotives. In 1946 and 1947, several drafts of a new, generously-dimensioned central station replacing the Wettiner Straße station emerged. The former Hauptbahnhof would have been renamed Bahnhof Dresden Prager Straße and passenger services would have operated only through the north hall and from the east side. Initially a postal station was planned for the remaining area. This was abandoned in the draft of 1947; the south hall would now also be used for passenger operations, while the central hall would be used for any purpose.

It is not absolutely certain why these plans ultimately did not proceed. Possible reasons were financial problems, material shortages, labour shortages and general planning uncertainty during a period of social and political changes. A planned new entrance building on Wiener Platz with an attached new administration building for the Reichsbahndirektion Railway division of Dresden was also not realised.[17]

The remaining structure was restored from 1950 in a similar but simpler form, due to economic difficulties and the shortage of skilled workers. The roof, which had previously been partially covered with glass, was temporarily covered with wood, board and slate. The station building itself was only partially restored. In particular, the buildings south of the main hall remained hollow ruins, although the outer walls implied a complete reconstruction. The intact steel construction of the dome over the main hall was also externally covered with wood and slate and a coffered ceiling was built inside it. The construction work was not largely completed until the early 1960s. One of the last measures was the modification of the clock towers on either side of the entrance portal to fit the “skeletal” facade.[18]

In the coming decades, the station's makeshift parking and traffic arrangements and its power lines shaped perceptions of it.

East German times

From the 1960s the station again became an important hub for long-distance services from Western Europe and Scandinavia to Southeastern Europe. The well-known services of this period were the Vindobona (Berlin–Vienna), the Hungaria (Berlin–Budapest) and the Meridian (Malmö–Bar).

As part of the change in traction, trains hauled by electric locomotives reached Dresden from Freiberg for the first time in September 1966.[19] A good ten years later–on 24 September 1977–the final steam-hauled service departed the station towards Berlin as the Dresden Express.[19] Steam-hauled passenger trains were still seen running towards Upper Lusatia until the late 1980s.[19] Since the headroom in the western part of the station area was insufficient, the Hohe Brücke (bridge) had to be demolished to permit the electrification of the railway lines.

Within the city and the surrounding area, the Dresden S-Bahn has carried the majority of traffic to the station since 1973 and has operated as its central point. In 1978, the Dresden Hauptbahnhof was heritage-listed.

On the night of 30 September and 1 October 1989, six so-called refugee trains were operated from Prague through Dresden station and the territory of the German Democratic Republic to West Germany. Two hours before the news spread to the West German media about these trips, a few quick and resolute citizens managed to jump on a train during transit. More East Germans were queuing in the West German embassy in Prague and so more trains were run. Therefore, on the following days, more and more disgruntled citizens collected at the station, amounting to about 20,000 people on the night of 4 and 5 October, according to the police. While the majority of the demonstrators and the security forces confronted each other that night in Lenin-Platz (now Wiener Platz), three of the expected trains from Prague passed on the southern tracks of the Hauptbahnhof but were hardly noticed. Due to the critical situation in Dresden, five additional special trains were diverted via Vojtanov and Bad Brambach to Plauen. Most demonstrators were peaceful, but there were also violent clashes between about 3,000 demonstrators and the Volkspolizei and property at the station was damaged.[20][21] In the following days, peaceful demonstrations took place in Lenin-Platz and the adjacent Prager Straße, resulting in the beginning of a dialogue on state power at the local level with the establishment of the Group of 20 (Gruppe der 20) on the evening 8 October.[22]

With a combined 156 arrivals and departures of scheduled long-distance trains per day in the station in the summer 1989 timetable, it was the third most important node in the network of Deutsche Reichsbahn, after Berlin and Leipzig.[23]

After the political changes in the GDR

Since the 1990s, Dresden has gradually become part of the Intercity network. From 1991, individual Intercity services ran via Leipzig and the Thuringian Railway to Frankfurt am Main and these service have run every two hours since 1992. The first pair of EuroCity services ran from Dresden to Paris-Est over the same route on 2 June 1991.[24] That same year, InterRegio trains served Dresden for the first time. The 2048/2049 and 2044/2143 trains pairs ran between Cologne and Dresden.[24] Later, other connections were added. In 1993, a north-south connection through Dresden was included in the EuroCity network and some of the eight EC trains that now run to Prague, Vienna and Budapest were introduced.

On 25 September 1994, scheduled Intercity-Express (ICE) services operated for the first time to the station. The ICE Elbkurier ran in the evening on the line from the Zoo station in Berlin to Dresden in one hour and 58 minutes. In the morning there was a service in the opposite direction. The introduction of the ICE meant that construction work at the station had to be carried out in advance.[25]

Until the timetable change on 28 May 2000, a pair of trains ICE ran daily via Berlin to Dresden, then the hourly ICE line 50 service, which has continued to the present, was introduced from Dresden to Frankfurt via Leipzig, eliminating the connection via Berlin. Dresden station became the starting point of the central east–west connection in the German ICE network.

This change caused changes in locomotive-hauled long-distance operations, since Dresden was now served almost exclusively in the north–south direction by Intercity (IC) and EuroCity (EC) trains. There were other related changes to the IC/EC network. So already the service, subsequently numbered EC/IC 27 (Prague–Dresden–Berlin), received a through connection to Hamburg in 1994 and in 2003 two pairs of trains continued to Vienna and a pair of trains continued to Aarhus in Denmark for the first time.

ICE TD (class 605) services ran on the Saxon-Franconian trunk line to Nuremberg from 10 June 2001. These replaced InterRegio services that had been abandoned a year earlier. After the 2002 Elbe flood and the resulting disruption of the line between Chemnitz and Dresden, as well as problems with the tilting systems, Deutsche Bahn discontinued the operation of the trainsets from the summer of 2003. Instead services were operated with Intercity trains until the end of long-distance services in 2006.

A suitcase bomb was discovered in the station by an explosive-detection dog on 6 June 2003. After the evacuation of the entire building, the police destroyed the suitcase bomb. The bomb consisted of a standard wheeled suitcase which contained an alarm clock, a pressure cooker, explosives and stones as well as an ignition device with fuse. According to experts, this bomb was capable of exploding.[26]

The fundamental renovation after 2000

The first restoration work took place in the 1990s. The bridges over federal highway 170 were renovated and the eastern building was given a new facade on the street side and new entrance steps.

A draft plan by Gerkan, Marg and Partners for the modernisation of the station in the mid-1990s envisaged part of the central hall remodelled as a market as well as the building of an office and hotel tower.[27] This design was not realised.

At the end of December 2000, the Board of Deutsche Bahn, let a contract for modernisation work. The planned construction costs amounted to approximately DM 100 million, which was funded from the federal government's remediation funds, Deutsche Bahn's own funds and a grant from the state of Saxony (DM 13 million). The completion of construction works was scheduled for the spring of 2003.[28]

The extensive redevelopment had already commenced in 2000 with the commissioning of the Leipzig remote electronic control centre. The additional redevelopment included the renovation of the entrance building and the train shed roof, track work of the north and south hall and changes to the track and signaling systems. To ensure uninterrupted movement of trains, the track structures of the north hall were first rehabilitated and recommissioned in November 2003. Subsequently, the renovation of the track structures of the south hall began at the end of 2004. The train shed roof was renovated from 2002 and the station building was renovated from the end of 2003. Because of the construction, shops were accommodated in containers in the station hall from 2002 to 2006. The dome above the connection hall between the two halls, which is up to 34 metres high, the connecting hall and the large waiting rooms were restored to their historical designs. A travel centre and a supermarket were opened in the waiting rooms in July 2006, simultaneously with the commissioning of the central hall. The high-level platforms are now reached via escalators and lifts.

In December 2007, the newly designed network of tracks was put into operation on the station's south side, except for platform 1, which was opened at the end of 2008.[29] In addition, the two freight train tracks outside the south hall were rebuilt, but omitting the platform between the tracks that had been built with the tracks in about 1930.

The 2002 floods delayed the renovation work significantly. On 12 August 2002, the station was closed due to flooding by the Weißeritz, which had returned to its old route through Dresden and followed the route of the line to Chemnitz to reach the Hauptbahnhof, reaching a height of up to 1.50 m at the station.[30] Water, mud and debris caused damage of €42 million.[31] Many sections of track were impassable for a long time, especially towards Chemnitz. After a few regional trains reached the station on 2 September 2002, a long-distance train also reached it.[30] The building was, in part, demolished down to its basement, except for its facade;[31] this work lasted until the end of 2004.

The cost of the remediation amounted to about €250 million up to November 2006. Of this amount, €85 million was spent on the membrane roof and €55 million on the entrance building. The federal government contributed about €100 million of this and the government of Saxony contributed about €11 million. The renewal of the elevated track structures in the south hall had still not been carried out at that time, it would be supported by the federal government with some €54 million.

The inauguration of the renovated station took place under the dome of the lobby on the evening of 10 November 2006.[32] It was carried out in 2006 to coincide with the celebration of the 800-year anniversary of the city. The opening meant the end of a significant obstacle for tourism, but the renovations have not yet finished even in 2014.

After 20 months of construction, carried out as part of the federal economic stimulus package, the refurbishment of the station's energy systems were completed in June 2011. This construction work included the renovation of the royal pavilion.[33] Since the summer of 2011, Deutsche Bahn has been developing a future retail space under the tracks of the north and south hall of the station. Around €25 million were expected to be invested by 2014.[34] It has around 40 storefronts with a total area of 14,000 square metres.[35] The first new stores opened in August 2013, although construction work had not been completed in April 2014.[36] The second stage of the development of the Dresden railway node was planned in 2009 to be completed in 2011.[37] However, this construction phase was not included in the 2011–2015 federal Investment Framework Plan (Investitionsrahmenplan) and construction is not currently scheduled (as of 2012). In September 2013, Deutsche Bahn said that the platforms of the central hall would be replaced by 2019 and they would also be slightly raised.[38]

The Förderverein Dresdner Hauptbahnhof e. V. (Friends of Dresden Hauptbahnhof) supported the renovation and enabled the recovery of some details about the required conservation measures. So broken decorative elements on a sandstone facade of the clock tower were returned to their correct places, windows were equipped with arches and architraves and the crowning group statue of Saxonia with personifications of science and technology have been restored.[39]

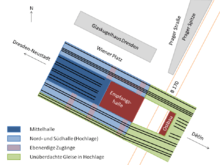

Building

The station building is oriented in a northwest–southeast direction and is divided along its longitudinal axis into three train sheds with eye-catching arched roofs. The lobby is located to the east of the central and largest of the three buildings and it is centered between the outer halls; it has an approximately square plan. A small forecourt facing on to federal highway (Bundesstraße) 170 is in front of the main entrance. This road passes at roughly right angles under the railways running through the other two halls.

The tripartite platform hall covers an area that is 60 metres wide and 186 metres long. The iron arch structure of the roof rises up to 32 metres high and has a width of 59 metres. The spans of the train sheds are 31 or 32 metres and 19 metres wide. The dimensions of the roof were necessary during the days of steam so that smoke could be blown away.

On the other side of federal highway 170 opposite the main entrance is the station's east wing. Several bay platforms are arranged in an elevated position between the running lines from the north and south hall. These are mainly used for stabling short sets.

Impressive entrances to the station building were built not only from the east, but also from the north and the south. Additionally from these sides there are direct entrances to the central train shed under the elevated through tracks. The entrance from Wiener Platz to the station hall was also perceived as the main entrance during construction, which led to contemporary criticism that "the organic development of the building had to suffer from the needs of two main entrances with one having greater architectural significance and the other responding more to the needs of users."[40]

.jpg)

.jpg)

In the northwest is the royal pavilion (Königspavillon), which is built in the Baroque Revival style. Originally it served to receive state guests of the Kingdom of Saxony. After the end of the monarchy in 1918, it contained a ticket office before it was again reserved for functions and receiving dignitaries during the Third Reich. From 1950, the royal pavilion contained the Kino im Hauptbahnhof (cinema in the station), which had more than 170 places. On 31 December 2000, Deutsche Bahn dismissed the operator and the Pavilion has since been unused. During a renovation to make it energy-efficient in 2010, the facade of the Pavilion was repaired and new windows and a new roof were installed. In April 2014, the royal pavilion is to be opened as an additional entrance to the station, allowing direct access to platforms 17, 18 and 19 from the north-west side. In the royal pavilion itself there will be room for cultural projects and art exhibitions.[36] Originally there was another entrance to the Pavilion on the north side. Eliminating it led to criticism from architects and the press, as the royal pavilion would now not be integrated into a harmonious structure.[3]

Among the elevated tracks of the north and south hall there was originally facilities for loading luggage and offices for the management and inspection of operations (north hall) and rooms for the staff (south hall). Since the redevelopment there are shops for travel necessities below the eastern part of the north hall and a waiting hall with its own lost property office and sanitary facilities under a part of the south hall. The development of further rooms below the north hall and south hall is still continuing (as of 2013).

Platforms

The central train shed today serves as a terminal station with seven tracks running from the west. Originally, however, it housed only six platform tracks. Even before the Second World War another platform track was integrated into the train shed, the current platform 14. This change involved the abolition of two luggage platforms, leaving only the former luggage platform between platforms 6 and 9. The tracks of the central part of the station are approximately at street level, while all the through tracks run in a second level which is about 4.50 metres higher.

The north and south halls house three through tracks (without platforms) that run in a southeasterly direction past the terminal hall. The eastern sections of platforms 1 and 2 are also referred to as platforms 1a and 2a. The north hall also houses an additional through track without platform. During the refurbishment works carried out since 2000, the platform height was adjusted to meet current standards. The east wing originally had a second terminal track, but only platform track 4 is still in use.

In addition to structural changes, the system of operations has also changed. It was initially mainly operated with tracks arranged according to direction (that is with fast and slow lines in the same direction). The tracks are now largely arranged as discrete lines (for instance some tracks are dedicated to S-Bahn services). The following table gives an overview of the aspects of the platform and their original and current use (November 2009). The island platform added between the freight tracks south of the south hall in the 1930s has not existed since the reorganisation in the new millennium and therefore it is not shown in the table.

| Platform | Location | Usable length [m][41] | Height [cm][41] | Use in 2013 | Original use[42] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | South hall | 341 | 55 | Long-distance traffic towards Leipzig and Prague, night train from Zürich/Oberhausen | from Berlin, Leipzig, Meißen to Bodenbach, Děčín, Pirna |

| 1a | East hall (continuation of platform 1 outside the south hall) | 210 | 55 | ||

| 2 | South hall | 341 | 55 | Long-distance traffic to Düsseldorf, regional traffic to Hoyerswerda and Elsterwerda | from Berlin, Leipzig, Meißen to Bodenbach, Děčín, Pirna |

| 2a | East hall (continuation of platform 2 outside the south hall) | 192 | 55 | Long-distance traffic towards Prague | |

| 3 | South hall | 416 | 76 | Long-distance traffic to and from Leipzig, night train to Budapest/Vienna | from Berlin, Leipzig, Meißen to Bodenbach, Děčín, Pirna |

| 4 | East hall | 187 | 55 | Additional peak hour services of the S-Bahn towards Schöna, arrivals of the SE19 from Altenberg | to Bodenbach |

| – | East hall | Platform no longer exists | from Bodenbach | ||

| 6 | Central hall | 318 | 38 | Storage area | from and to Chemnitz |

| 9 | Central hall | 289 | 36 | Regional traffic from and to Cottbus and Hoyerswerda | from Görlitz to Reichenbach |

| 10 | Central hall | 289 | 36 | Regional traffic from and to Leipzig | from Tharandt |

| 11 | Central hall | 310 | 38 | Regional traffic from and to Görlitz and Zittau | to Tharandt |

| 12 | Central hall | 310 | 38 | Regional traffic from and to Hof | from Reichenbach to Görlitz |

| 13 | Central hall | 363 | 55 | S-Bahn services from and to Tharandt and Freiberg, regional traffic from and to Zwickau | from and to Arnsdorf |

| 14 | Central hall | 363 | 55 | Regional traffic from and to Kamenz, S-Bahn traffic towards Tharandt | Platform did not originally exist |

| 17 | Central hall | 423 | 76 | Long-distance traffic to Berlin, night train to Zürich/Oberhausen, night train from Budapest/Wien | from Bodenbach, Děčín, Pirna to Berlin, Leipzig, Meißen |

| 18 | North hall | 258 / 251 | 55 / 76 | S-Bahn services from Dresden Airport and Meißen towards Pirna | from Bodenbach, Děčín, Pirna to Berlin, Leipzig, Meißen |

| 19 | North hall | 258 / 251 | 55 / 76 | S-Bahn services from Pirna to Dresden Airport and Meißen | from Bodenbach, Děčín, Pirna to Berlin, Leipzig, Meißen |

Roof construction

A special feature of the station is the renovated roof, which was designed by the British architect Sir Norman Foster. The previous panes of framed glass were replaced by 0.7 mm-thick glass fibre membranes which have been stretched between the arched halls. The membranes have double-sided Teflon coatings that are 0.1 mm-thick and are self-cleaning. It was the first time that a historic building had been treated with this new material.[43] Designed for a service life of 50 years, the membrane can resist tensile forces of up to about 150 kN per metre. It can be walked over by trained personnel with a safety harness.

The membrane is largely translucent during the daytime and reflects the light of the concourse back at night; the structure appears to be silver from the outside. Narrow slits between the membranes are left open over the hall arches, forming a total of 67 skylights. The roof area is about 33,000 square metres (of which 29,000 square metres is composed of glass fibre membrane), which covers a surface area about 24,500 square metres. The architects who won the competition emphasised their entry's relatively easy installation, low weight and low maintenance costs (self-cleaning). According to the Deutsche Bahn specifications, cooling is not required due to the "tent construction" of the roof even in bright sunlight.

The restoration was carried out between February 2001 and July 2006 with trains running through the station. 800 tons of material were installed in the two outer halls from elevated work platforms and more than 1600 tons of material were installed in the central hall. On 15 May 2001, workers began with the removal of the old glass roof. Some of the old steel beams were rebuilt and some new ones have been inserted as wind bracing between the hall arches. Secondary structures were then built to attach the membranes on the beams. A total of more than 100,000 screws were installed, some of which also replaced rivets on the historic hall arches. A service lift was also installed.

The planning began in 1997 and originally a full canopy covering the outer platforms was envisaged, but this was rejected in 2000. Instead it was decided to take up an option to extend the two outer roofs by 200 metres to the east above the outer platforms using a membrane roof.

The membrane roof has been damaged several times during bad weather. In the winter of 2010/2011, eight cracks, which were up to two metres wide, were formed. Responsibility for the damage was still being contested in court in January 2013.[44]

Main entrance and lobby

The main entrance of the station building forms part of a large circular portal window arch. The portal is installed in the massive Avant-corps that dominates the centre of the facade. In addition there is a statue of Saxonia, the embodiment of the spirit of Saxony, which is arranged between allegories of science and technology. Both the portal of the entrance building and the clock towers on both sides show the association of the station with the architectural style of Historicism, which was typical of the buildings of the kingdom of Saxony in Dresden.

The entrance building consists of two elongated, T-shaped crossings, which intersect under the large glass dome of the hall. The main corridor leads to the central hall, while the side halls can be reached by passages running parallel to the cross passage through the central hall. During the renovation of the business and administrative areas, large parts of the station building were converted into facades and additional areas of glass were inserted into its roofs for daylighting.

While the interiors of the lobby are now simply decorated, they appeared much more lively before the destruction of the station during World War II. Ceiling paintings and the 26 emblems of the administrative districts of the Kingdom of Saxony in their heraldic colours adorned the lobby. The waiting rooms of the first and second class were graced with large murals made of porcelain tiles to the design of Prof. Julius Storm of Meissen.[45]

For a long time many locals have met at the Unterm Strick (“rope end"), which is just below the center of the dome of Dresden station. Before the renovation of the station, a so-called rope hung here in the middle of the entrance hall. Although nothing has hung here since the station redevelopment, the old name is still used for this meeting place by many in Dresden.

At this point of the roof, there is now a round cushion, 15 metres in diameter and made of ETFE foil. Its height can be adjusted and it serves mainly to regulate the ventilation.

In the upper floor of the station there has been a DB Lounge for first class passengers and frequent travellers since September 2006. In the entrance building there are shops for travel needs. It includes leased retail space of 3,969 square metres in addition to the space below the elevated tracks of the south hall; this provision is low compared to other metropolitan stations.

Operations

As an important transport hub in Dresden, the station is linked to various transport services. It is not only a stop on the rail network, but it is also an important transfer point for public transport, a grade-separated crossing of two main roads and the beginning of the pedestrianised route through the inner city.

Railway lines and operations

Unifying railways

The Dresden station is located on three electrified double-track main lines:

- The Děčín–Dresden railway (also called the Elbtalbahn–Elbe Valley Railway) (route 6240) passes through the station running over two lateral elevated railway tracks and runs to the south-east. It connects with Děčín and Prague through the valley of the Elbe. The section to Pirna is designed for speeds up to 160 km/h.

- From Dresden Hauptbahnhof to the vicinity of Dresden-Neustadt station there is a parallel single or double-track line for freight traffic (route 6241). The double track line branches off in Dresden Hauptbahnhof and runs south of the south hall. The line is single track from the vicinity of Dresden Mitte station over the Marien Bridge to Dresden-Neustadt station and it is shared by passenger trains and runs as a single track to the line to Dresden-Klotzsche.

- The Pirna–Coswig S-Bahn line (route 6239) runs parallel to the Elbe Valley Railway; it runs through the northern hall of Dresden station.

- The Dresden–Werdau railway (route 6258) starts in the station and branches on the western approach over a grade-separated junction. It represents the first section of Saxon-Franconian trunk line via Chemnitz, Zwickau and Hof to Nuremberg.

The Hauptbahnhof is also connected with railway to Berlin via the triangle of rail tracks between Dresden Freiberger Straße and Dresden Mitte and with the railway to Leipzig and railway to Görlitz via Dresden-Neustadt.

Components of the station

An electronic interlocking controls the Dresden junction to the limits on Dresden station. For operational purposes, Dresden Hauptbahnhof (Hbf) is part is part of the Dresden “operating agency” (Betriebsstelle; DDRE) which consists of the following station parts:

- Dresden Hbf

- Dresden-Altstadt

- Dresden Freiberger Straße

- Dresden Freiberger Straße platform

- Dresden Mitte

- Dresden-Neustadt Pbf (passenger station)

- Dresden-Neustadt Gbf (freight yard)

All lines to Dresden have entry signals, as do the opposite tracks. The operating agency of Dresden has a total of 15 entry signals.

Rail operations

Two long-distance railway corridors intersect in Dresden. In addition to the important long-distance route to Leipzig, there is also the north–south corridor from Berlin via Dresden and Prague to Vienna. A third corridor from Nuremberg to Wrocław has lost its importance in Germany and Poland and is no longer served by long-distance traffic.

Journey times are as follows from Dresden to:

- Leipzig (120 km): 65 minutes, with stops in Dresden-Neustadt and Riesa; corresponding to an average speed of 110 km/h;

- Berlin (Berlin Hauptbahnhof, low level) (182 km): 128 minutes, with stops in Dresden-Neustadt (some trains), Elsterwerda (some trains) and Berlin-Südkreuz; corresponding to an average speed of 85 km/h;

- Prague (Holešovice) (191 km) 126 minutes, with stops in Bad Schandau, Děčín and Ústí nad Labem; corresponding to an average speed of 90 km/h.

In the plans of the European Union, the station is the starting point of "Pan-European Corridors III and IV" to Kiev and southeast Europe.

Train services

The station is served by the following services (incomplete list):[46]

| Preceding station | DB Fernverkehr | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

towards Warnemünde | IC 17 via Berlin | Terminus | ||

towards Wiesbaden | ICE 50 | Terminus | ||

towards Hamburg-Altona | IC/EC 27 every 2 hours | towards Prague |

||

| IC/EC 27 1 train pair | towards Budapest |

|||

towards Cologne | IC 55 | Terminus | ||

| Preceding station | DB Regio | Following station | ||

Dresden Mitte toward Hoyerswerda | RE 15 | Terminus | ||

Dresden Mitte toward Cottbus Hbf | RE 18 | Terminus | ||

| Terminus | RE 20 Wanderexpress Bohemica | Dresden-Strehlen toward Litoměřice město |

||

Dresden Mitte toward Leipzig Hbf | RE 50 | Terminus | ||

Dresden-Friedrichstadt toward Elsterwerda-Biehla | RB 31 | Terminus | ||

| Preceding station | Mitteldeutsche Regiobahn | Following station | ||

Tharandt toward Hof Hbf | RE 3 | Terminus | ||

toward Zwickau Hbf | RB 30 | Terminus | ||

| Preceding station | Städtebahn Sachsen | Following station | ||

| Terminus | RE 19 Wintersport Express | Dresden-Strehlen toward Kurort Altenberg |

||

| Terminus | RB 34 | Dresden Mitte toward Kamenz |

||

| Preceding station | Vogtlandbahn | Following station | ||

| Terminus | RE 1 Trilex | Dresden Mitte |

||

| Terminus | RE 2 Trilex | Dresden Mitte |

||

| Terminus | RB 60 Trilex | Dresden Mitte toward Görlitz |

||

| Terminus | RB 61 Trilex | Dresden Mitte toward Zittau |

||

| Preceding station | Dresden S-Bahn | Following station | ||

toward Meißen Triebischtal | S 1 | toward Schöna |

||

toward Dresden Flughafen | S 2 | toward Pirna |

||

Dresden-Plauen toward Freiberg (Sachs) | S 3 | Terminus |

Traffic

Each day the station is used by around 60,000 passengers, 381 trains (including 50 long-distance services), including up to ten S-Bahn services each hour. In passenger traffic it is served by services operated by DB Fernverkehr (long-distance), DB Regio (Südost), Städtebahn Sachsen and Vogtlandbahn (under the brand name of Trilex). In addition, about 200 freight trains operated by different railway companies pass the station daily.

The most common direct destination outside the area of the Dresden S-Bahn is Leipzig with up to 32 services daily. The other most frequent long-distance destinations are Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt, Wiesbaden, Prague and Budapest. The Saxon-Franconian trunk line via Chemnitz and the Vogtland to Nuremberg has been discontinued in recent years, despite the growth of long-distance traffic and is now only operated by DB Regio as far as Hof.

The number of direct connections to the station mean that it has national significance as an interchange. It is one of the 21 stations of the highest category as classified by DB Station&Service.

Transport links

Public transportation

The station is the main inner-city hub for national passenger services. From the outset, it was the centre of the tram network of the Dresdner Verkehrsbetriebe (Dresden Transport) or its predecessor organisations. Today, along with Postplatz, Albertplatz and Pirnaischer Platz, it is one of the four major tram hubs of the city. The first bus service was operated in Dresden from April 1914 via the station as the overland buses of the Kraftverkehrsgesellschaft Freistaat Sachsen (KVG) from 1919 until the end of World War II.

Tram stops are located on the station forecourt fronting highway B170 and on Wiener Platz. The distance from the centre of the station to each of the tram stops is about 100 metres. The connecting path runs at ground level from the head of the platforms. Also in front of the entrance building is the bus stop, which is served by city and regional buses. As part of further restructuring, a new central bus station (Zentraler Omnibus Bahnhof, ZOB) is being built at the western end of Wiener Platz. Bus passengers will then be able to use the station entrance by the royal pavilion.

Four tram lines (3, 7, 8, 10), a city bus route (66) and several regional bus services operated by Regionalverkehr Dresden (Regional Transport Dresden), line 261 operated by the Pirna-Sebnitz Upper Elbe Transport Company (Oberelbischen Verkehrsgesellschaft Pirna-Sebnitz) and other services operated by long-distance transport companies regularly stop at the station. Apart from destinations in the surrounding area of Dresden, services are also operated to Annaberg-Buchholz, Olbernhau and Mittweida as well as Teplice in the Czech Republic, among other places. In addition, tram lines 9 and 11 stop at the Hauptbahnhof Nord stop, which is about 150 metres to the northeast of the station. In the Bayerischen Straße to the south of the station are the bus stops of several long-distance bus services. After the completion of the planned ZOB, this is to be served by all regional and long-distance bus services.

Private transport

Stopping places for cars are provided near the entrances on the south side of the station. An underground car park with 350 parking spaces is located at Wiener Platz in front of the northern entrances of the station. It is reached from the road tunnel under the Platz running to the east. Further parking is available in parking garages and parking lots along Prager Straße and south of the station.

Awards

The renovated station in Dresden received the 2007 Renault Traffic Future Award for special transport architecture.[47] In addition, the architectural firm of Foster and Partners received a second place in the award of the Stirling Prize in the same year and in 2008 the new roof of the station hall received the Brunel Award, an award for railway design.[48] In August 2014, the station was given an award by Allianz pro Schiene entitled "Station of the Year in the category of large city railway station". The jury praised the station as being a "monument of a clear, lilting lightness."[49]

Notes

- Eisenbahnatlas Deutschland (German railway atlas) (2009/2010 ed.). Schweers + Wall. 2009. ISBN 978-3-89494-139-0.

- "Stationspreisliste 2020" [Station price list 2020] (PDF) (in German). DB Station&Service. 4 November 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Kaiß/Hengst: Dresdens Eisenbahn, pp. 10f

- Berger/Weisbrod: Über 150 Jahre Dresdener Bahnhöfe”, p. 16

- Kaiß/Hengst: Dresdens Eisenbahn, p. 6

- Hundert Jahre Dresdner Hauptbahnhof 1898–1998 [One Hundred Years Dresden Hauptbahnhof 1898- 1998] (in German). Dresden Transport Museum. p. 16.

- Berger/Weisbrod: Über 150 Jahre Dresdener Bahnhöfe”, pp. 24f

- Hundert Jahre Dresdner Hauptbahnhof 1898–1998 [One Hundred Years Dresden Hauptbahnhof 1898- 1998] (in German). Dresden Transport Museum. p. 24.

- Ein Zelt für Züge. Der Dresdner Hauptbahnhof 2006 [A tent for trains. The Dresden Hauptbahnhof in 2006] (in German). Leipzig: Deutsche Bahn. 2006. p. 8. (Brochure: 42 A4 pages)

- Reichler: Dresden Hauptbahnhof, p. 31

- Reichler: Dresden Hauptbahnhof, p. 36.

- Kaiß/Hengst: Dresdens Eisenbahn, pp. 22ff

- Kaiß/Hengst: Dresdens Eisenbahn, pp. 27f

- Matthias Neutzner (1999). ""Der Wehrmacht so nahe verwandt" – Eisenbahn in Dresden 1939 bis 1945". Dresdner Geschichtsbuch 5 (in German). Dresden City Museum. p. 212ff.

- Seydewitz, Max (1955). Zerstörung und Wiederaufbau von Dresden (in German). Berlin. pp. 94–96.

- Reichler: Dresden Hauptbahnhof, p. 55.

- Kaiß/Hengst: Dresdens Eisenbahn, pp. 44ff.

- Kaiß/Hengst: Dresdens Eisenbahn, pp. 52ff

- Reichler: Dresden Hauptbahnhof, p. 64

- Kaiß/Hengst: Dresdens Eisenbahn, p. 60

- Archive of the Stasi Records Agency, report of the Ministry of State Security

- Hundert Jahre Dresdner Hauptbahnhof 1898–1998 [One Hundred Years Dresden Hauptbahnhof 1898- 1998] (in German). Dresden Transport Museum. pp. 50/51.

- Ralph Seidel (2005). Der Einfluss veränderter Rahmenbedingungen auf Netzgestalt und Frequenzen im Schienenpersonenfernverkehr Deutschlands. Dissertation at the University of Leipzig (in German). Leipzig. p. 48.

- Berger/Weisbrod. Über 150 Jahre Dresdener Bahnhöfe (in German). p. 60f.

- "Dresden an ICE-Strecke nach Berlin angeschlossen". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German) (222). 1994. p. 6. ISSN 0174-4917.

- "Dresdner Kofferbombe: Verdächtiger gesteht die Tat". Spiegel Online (in German). 22 September 2003. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Bund Deutscher Architekten / Deutsche Bahn AG / Förderverein Deutsche Architekturzentrum, ed. (1996). Renaissance der Bahnhöfe: Die Stadt im 21. Jahrhundert (in German). Wiesbaden: Vieweg-Verlag. p. 70 f. ISBN 3-528-08139-2.

- "Sanierung des Dresdner Hauptbahnhofs". Eisenbahn-Revue International (in German) (3): 101. 2001. ISSN 1421-2811.

- "Bauarbeiten zur Inbetriebnahme der Gleise Südseite im Hauptbahnhof Dresden" (Press release) (in German). Deutsche Bahn. 22 November 2007.

- "Hochwasser in Europa". Eisenbahn-Revue International (in German) (10): 460–463. 2002. ISSN 1421-2811.

- "Hochwasser-Zwischenbilanz". Eisenbahn-Revue International (in German) (4): 148. 2003. ISSN 1421-2811.

- "Schmuckstück lockt Reisende". Sächsische Zeitung (in German). 11 November 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Energetische Sanierung des Hauptbahnhofs Dresden abgeschlossen" (Press release) (in German). Deutsche Bahn. 15 June 2011.

- Julia Vollmer (7 February 2013). "Rund 50 neue Geschäfte - Dresdner Hauptbahnhof soll künftig Kundenmagnet werden". Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten (in German).

- "Auftakt für 25-Millionen-Projekt: Innenausbau im Dresdner Hauptbahnhof geht in die Realisierung" (Press release) (in German). Deutsche Bahn. 15 June 2011.

- "Shoppen unter Gleisen: Im Juli eröffnen die ersten Läden im neuen Hauptbahnhof". Sächsische Zeitung (in German). 8 February 2013.

- "Verkehrsinvestitionsbericht 2008" (PDF; 10.34 mb). Printed matter 16/11850 (in German). Deutscher Bundestag. 3 February 2009.

- Tobias Winzer (16 September 2013). "Schlechtes Zeugnis für den Hauptbahnhof". Sächsische Zeitung (in German).

- Peter Bäumler (2006). "Förderverein für den Dresdner Hauptbahnhof". Dresdner Blätt'l (in German) (12).

- Hoßfeld, O (1892). "Die Preisbewerbung um die Gebäude des neuen Hauptbahnhofes in Dresden". Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung (CBV) (in German) (12).

- "Station information" (in German). Deutsche Bahn. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Hundert Jahre Dresdner Hauptbahnhof 1898–1998 (in German). Verkehrsmuseum Dresden. pp. 28f.

- "Renovation of the Hauptbahnhof" (in German). Das Neue Dresden. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- "Deutsche Bahn will Dreck auf Bahnhofsdach entfernen". Sächsische Zeitung (in German). 21 January 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- Berger, Manfred (1986). Historische Bahnhofsbauten (in German). 1. Berlin: Transpress, Verlag für Verkehrswesen. p. 116. ISBN 3 -344-00066-7.

- Timetables for Dresden Hbf station

- Roland Stimpel (1 December 2007). "Für nachhaltige Mobilität". German Architektenblatt (in German). Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "Hallendach des Dresdener Hauptbahnhofs und Redesign des ICE 1 mit "Brunel Award 2008" ausgezeichnet" (Press release) (in German). Deutsche Bahn AG. 30 September 2008.

- "Würdigung Dresden Hauptbahnhof: Das Schmuckstück" (PDF) (in German). www.allianz-pro-schiene.de. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

References

- Ein Zelt für Züge – Der Dresdner Hauptbahnhof 2006 (in German). Deutsche Bahn AG, Kommunikationsbüro Leipzig. November 2006. (brochure)

- Kurt Kaiß und Matthias Hengst (1994). Dresdens Eisenbahn: 1894–1994 (in German). Düsseldorf: Alba Publikation. ISBN 3-87094-350-5.

- Peter Reichler (1998). Dresden Hauptbahnhof. 150 Jahre Bahnhof in der Altstadt (in German). Egglham: Bufe-Fachbuch-Verlag. ISBN 3-922138-64-0.

- Manfred Berger and Manfred Weisbrod. Über 150 Jahre Dresdener Bahnhöfe (in German). Eisenbahn Journal special 6/91. ISBN 3-922404-27-8.

- Verkehrsmuseum Dresden (1998). Hundert Jahre Dresdner Hauptbahnhof 1898–1998 (in German). Leipzig: Unimedia. ISBN 3-932019-28-8.

- Christian Bedeschinski, ed. (2014). Hauptbahnhof Dresden – Das Tor zum Elbflorenz (in German). Berlin: VBN Verlag Bernd Neddermeyer. ISBN 978-3941712423.

External links

- Dresden Hauptbahnhof | Deutsche Bahn AG - Official DB site (in English).

- Foster + Partners - project description

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dresden Hauptbahnhof. |