Dounreay

Dounreay (/ˌduːnˈreɪ/;[1] Scottish Gaelic: Dùnrath) (Ordnance Survey grid reference NC982669) is on the north coast of Caithness, in the Highland area of Scotland and west of the town of Thurso. Dounreay was originally the site of Dounreay Castle (now a ruin)[2] and its name derives from the Gaelic for 'fort on a mound.'[3] Since the 1950s it has been the site of two nuclear establishments, for the development of prototype fast breeder reactors and submarine reactor testing. Most of these facilities are now being decommissioned.

| Dounreay | |

|---|---|

Dounreay Nuclear Power Development Establishment, 2006 | |

| |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 58.57814°N 3.75233°W |

| Commission date | 1955 |

| Decommission date | 1994 |

| Operator(s) | United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Nuclear |

| External links | |

| Website | www |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

grid reference NC9811366859 | |

History

Dounreay formed part of the battlefield of the Sandside Chase in 1437.

The site is used by the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (Dounreay Nuclear Power Development Establishment) and the Ministry of Defence (Vulcan Naval Reactor Test Establishment), and the site is best known for its five nuclear reactors, three owned and operated by the UKAEA[4] and two by the Ministry of Defence.

The nuclear power establishment was built on the site of a World War II airfield, called RAF Station Dounreay. It became HMS Tern (II) when the airfield was transferred to the Admiralty by RAF Coastal Command in 1944, as a satellite of HMS Tern at Twatt in Orkney. It never saw any action during the war and was placed into care and maintenance in 1949.

Dounreay is near the A836 road, about 9 miles (14 km) west of the town of Thurso, which grew rapidly when the research establishment was developed during the mid-20th century. The establishment remained a major element in the economy of Thurso and Caithness until 1994 when the government ordered that the reactors be closed for good; a large workforce employed in the clean-up of the site (which is scheduled to continue until at least 2025) remains.[4]

Toponymy

Robert Gordon's map of Caithness, 1642, uses Dounrae as the name of the castle.

William J. Watson's The Celtic Place-names of Scotland gives the origin as Dúnrath, and suggests that it may be a reference to a broch. This is the commonly accepted toponymy.

Dounreay Nuclear Power Development Establishment

Dounreay Nuclear Power Development Establishment was formed in 1955 primarily to pursue the UK Government policy of developing fast breeder reactor (FBR) technology.[4] The site was operated by the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA).[4] Three nuclear reactors were built there by the UKAEA, two of them FBRs plus a thermal research reactor used to test materials for the programme, and also fabrication and reprocessing facilities for the materials test rigs and for fuel for the FBRs.

Dounreay was chosen as the reactor location for safety reasons, in case of an explosion.[4] The first reactor built was surrounded by a 139-foot (42 m) steel sphere, still a prominent feature of the landscape. The sphere was constructed by the Motherwell Bridge Company.

Dounreay Materials Test Reactor

The first of the Dounreay reactors to achieve criticality was the Dounreay Materials Test Reactor (DMTR) in May 1958.[5] This reactor was used to test the performance of materials under intense neutron irradiation, particularly those intended for fuel cladding and other structural uses in a fast neutron reactor core. Test pieces were encased in uranium-bearing alloy to increase the already high neutron flux of the DIDO class reactor, and then chemically stripped of this coating after irradiation. DMTR was closed in 1969 when materials testing work was consolidated at Harwell Laboratory.

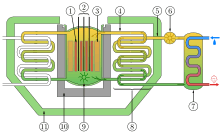

| 1 | Fissile Pu-239 core |

| 2 | Control rods |

| 3 | U-238 Breeder blanket |

| 4 | Primary NaK coolant loop |

| 5 | Secondary NaK coolant loop |

| 6 | Secondary NaK circulator |

| 7 | Secondary heat exchanger |

| 8 | Primary heat exchanger |

| 9 | Primary NaK circulator |

| 10 | Boronised graphite neutron shield |

| 11 | Radiation shield |

Dounreay Fast Reactor

The second operational reactor (although the first to commence construction) was the Dounreay Fast Reactor (DFR), which achieved criticality on 14 November 1959. Power was exported to the National Grid from 14 October 1962 until the reactor was taken offline for decommissioning in March 1977.[6]:81 During its operational lifespan, DFR produced over 600 million kWh of electricity.[7]

DFR and associated facilities cost £15m to build.[8] It was designed to generate 60 MW thermal power and achieve a 2% fuel burn up.[9] It reached 30 MWt in August 1962, and 60 MWt in July 1963 allowing it to produce its rated 14 MWe (electrical).[6]:74

DFR was a loop-type FBR cooled by primary and secondary NaK circuits, with 24 primary coolant loops. The reactor core was initially fuelled with uranium metal fuel stabilised with molybdenum and clad in niobium. The core was later used to test oxide fuels for PFR and provide experimental space to support overseas fast reactor fuel and materials development programmes.

It had over 5000 breeder elements of natural uranium in stainless steel arranged in an inner and outer breeder sections.[6]:75 Many were replaced in 1965.

Prototype Fast Reactor (PFR)

The third and final UKAEA-operated reactor to be built on the Dounreay site was the Prototype Fast Reactor (PFR).[10] In 1966 it was announced that the PFR would be built at Dounreay.[11] PFR was a pool-type fast breeder reactor, cooled by 1,500 tonnes[12] of liquid sodium and fuelled with MOX. The design output of PFR was 250 MWe (electrical).

It achieved criticality in 1974 and began supplying National Grid power in January 1975. There were many delays and reliability problems before reaching full power.[6]:79 It had three cooling circuits. Leaks in the sodium water steam generators shutdown one and then two of the cooling circuits in 1974 and 1975. By August 1976 it had reached 500 MWt[6]:80 (to produce about 166 MWe) and in 1985 it first reached its design output of 250 MWe.[11]

In 1988 it was announced that funding for FBR research was being cut from £105 m pa to £10 m pa and the PFR funding would end in 1994.[6]:87

The reactor was taken offline in 1994, marking the end of nuclear power generation at the site. It had supplied 9,250 GWh in all.[12] The lifetime load factor recorded by the IAEA was 26.9%.[13]

A remotely operated robot dubbed 'The Reactorsaurus' will be sent in to remove waste and contaminated equipment from this reactor as it is too dangerous a task for a human.[14] The control panel for the reactor has been earmarked for an exhibition on the reactor at the London Science Museum in 2016.[15]

Subsequent activity

Since the reactors have all been shut down,[4] care and maintenance of old plant and decommissioning activities have meant that Dounreay has still retained a large workforce. Commercial reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel and waste was stopped by the UK government in 1998 although some waste is still accepted from other nuclear facilities in special circumstances.

Nuclear Accidents and Leaks

Sodium Explosion

A 65 metre deep shaft at the plant was packed with radioactive waste and at least 2 kg of sodium and potassium.[16] On 10 May 1977 seawater, which flooded the shaft, reacted violently with the sodium and potassium, throwing off the massive steel and concrete lids of the shaft.[16] This explosion littered the area with radioactive particles.[16]

Radioactive Fuel Swarf

Tens of thousands of fragments of radioactive fuel escaped the plant between 1963 and 1984, resulting in fishing being banned within 2 km of the plant since 1997.[17] These milled shards are thought to have washed into the sea as cooling ponds were drained.[17] As of 2011, over 2,300 radioactive particles had been recovered from the sea floor, and over 480 from the beaches.[17]

Decommissioning

In September 1998 a safety audit of the plant was published by the Health and Safety Executive and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency. The results were damning and 143 recommendations were made. That November, the UKAEA announced a proposed timetable for accelerated decommissioning, reducing the original schedule from 100 years to 60 years. The cost was initially estimated at £4.3 billion.[18]

The Department of Trade and Industry was presented with three options for dealing with 25 tonnes of radioactive reactor fuel lying at Dounreay. The options were:

- to reprocess it at Dounreay,

- to reprocess some at Dounreay and some at Sellafield, or

- to store it above ground at Dounreay.

An accelerated decommissioning plan was welcomed by the Friends of the Earth Scotland, but the environmental group remained opposed to any further fuel reprocessing at the site.

Nuclear Decommissioning Authority ownership

On 1 April 2005 the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) became the owner of the site, with the UKAEA remaining as operator. Decommissioning of Dounreay was initially planned to bring the site to an interim care and surveillance state by 2036, and as a brownfield site by 2336, at a total cost of £2.9 billion.[19]

A new company called Dounreay Site Restoration Limited (DSRL) was formed as a subsidiary of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) to handle the decommissioning process. By May 2008, decommissioning cost estimates had been revised. Removal of all waste from the site was expected to take until the late 2070s to complete and the end-point of the project was scheduled for 2300.[20]

Apart from decommissioning the reactors, reprocessing plant, and associated facilities, there are five main environmental issues to be dealt with:

- A 65-metre (213 ft) deep shaft used for intermediate level nuclear waste disposal is contaminating some groundwater, and is threatened by coastal erosion in about 300 years time. The shaft was never designed as a waste depository, but was used as such on a very ad-hoc and poorly monitored basis, without reliable waste disposal records being kept. In origin it is a relic of a process by which a waste-discharge pipe was constructed. The pipe was designed to discharge waste into the sea. Historic use of the shaft as a waste depository has resulted in one hydrogen gas explosion[21] caused by sodium and potassium wastes reacting with water. At one time it was normal for workers to fire rifles into the shaft to sink polythene bags floating on water.[22]

- Irradiated nuclear fuel particles on the seabed near the plant,[4] estimated to be about several hundreds of thousands in number.[23] The beach has been closed since 1983 due to this danger,[4] caused by old fuel rod fragments being pumped into the sea.[4] In 2008, a clean-up project using Geiger counter-fitted robot submarines will search out and retrieve each particle individually, a process that will take years.[4] The particles still wash ashore, including as at 2009, 137 fewer radioactive particles on the publicly accessible but privately owned close by Sandside Bay beach and one at a popular tourist beach at Dunnet.[24] In 2012 a two million becquerel particle was found at Sandside beach, twice as radioactive as any particle previously found.[25]

- 18,000 cubic metres (640,000 cu ft) of radiologically contaminated land, and 28,000 cubic metres (990,000 cu ft) of chemically contaminated land.

- 1,350 cubic metres (48,000 cu ft) of high and medium active liquors and 2,550 cubic metres (90,000 cu ft) of unconditioned intermediate level nuclear waste in store.

- 1,500 metric tons (1,500 long tons) of sodium, of which 900 metric tons (890 long tons) are radioactively contaminated from the Prototype Fast Reactor.

Historically much of Dounreay's nuclear waste management was poor. On 18 September 2006, Norman Harrison, acting chief operating officer, predicted that more problems will be encountered from old practices at the site as the decommissioning effort continues. Some parts of the plant are being entered for the first time in 50 years.[26]

In 2007 UKAEA pleaded guilty to four charges under the Radioactive Substances Act 1960 relating to activities between 1963 and 1984, one of disposing of radioactive waste at a landfill site at the plant between 1963 and 1975, and three of illegally dumping radioactive waste and releasing nuclear fuel particles into the sea,[27][28] resulting in a fine of £140,000.[29]

In 2007 a new decommissioning plan was agreed, with a schedule of 25 years and a cost of £2.9 billion, a year later revised to 17 years at a cost of £2.6 billion.[18]

Due to the uranium and plutonium held at the site, it is considered a security risk and there is a high police presence.[4] The fuel elements, known as "exotics", are to be removed to Sellafield for reprocessing, starting in 2014 or 2015.[30]

In 2013 the detail design of the major project to decommission the intermediate level waste shaft was completed, and work should begin later in the year. The work will include the recovery and packaging of over 1,500 tonnes of radioactive waste.[31] As of 2013, the "interim end state" planned date had been brought forward to 2022–2025.[32] In March 2014 firefighters extinguished a small fire in an area used to store low-level nuclear waste.[33]

On 7 October 2014 a fire on the PFR site led to a "release of radioactivity via an unauthorised route". The Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) concluded that "procedural non-compliances and behavioural practices" led to the fire, and served an improvement notice on Dounreay Site Restoration Limited.[34][35] In 2015 decommissioning staff expressed a lack of confidence in management at the plant and fear for their safety.[36]

In 2016 the task of dismantling the PFR core commenced.[37] Plans were also announced to move about 700 kg (1,500 lb) of waste Highly Enriched Uranium to the United States.[38][39]

On 7 June 2019, there was a low-level radioactive contamination incident which led to the evacuation of the site. A DSRL spokesman said: "There was no risk to members of the public, no increased risk to the workforce and no release to the environment".[40]

On 23 December 2019, the NDA announced completion of the transfer of all plutonium from Dounreay to Sellafield (the centre of excellence for plutonium management) where all significant UK stocks of this material are now held.[41]

Framework contracts

In April 2019, Dounreay Site Restoration Limited (DSRL) awarded six framework contracts for decommissioning services at Dounreay. The total value of these contracts is estimated to be £400 million.[42]

Vulcan NRTE

The Vulcan Naval Reactor Test Establishment (NRTE) (formerly HMS Vulcan) is a Ministry of Defence (MoD) establishment housing the prototype nuclear propulsion plants of the type operated by the Royal Navy in its submarine fleet. Originally it was known as the Admiralty Reactor Test Establishment (ARTE).

For over 40 years Vulcan has been the cornerstone of the Royal Navy's nuclear propulsion programme, testing and proving the operation of five generations of reactor core. Its reactors have significantly led the operational submarine plants in terms of operation hours, proving systems, procedures and safety. The reactors were run at higher levels of intensity than those on submarines with the intention of discovering any system problems before they might be encountered on board submarines.[43][44]

Rolls-Royce, which designs and procures all the reactor plants for the Royal Navy from its Derby offices, operates Vulcan on behalf of the MoD and employs around 280 staff there, led by a small team of staff from the Royal Navy. Reactors developed include the PWR1 and PWR2.

In 2011 the MoD stated that NRTE could be scaled down or closed after 2015 when the current series of tests ends. Computer modelling and confidence in new reactor designs meant testing would no longer be necessary.[45] The cost of decommissioning NRTE facilities when they become redundant, including nuclear waste disposal, was estimated at £2.1 billion in 2005.[46] Its final reactor shut down on 21 July 2015, with post operational work continuing to 2022.[44]

Dounreay Submarine Prototype 1 (DSMP1)

The first reactor, PWR1, is known as Dounreay Submarine Prototype 1 (DSMP1). The reactor plant was recognised by the Royal Navy as one of Her Majesty's Submarines (HMS) and was commissioned as HMS Vulcan in 1963. It went critical in 1965. HMS Vulcan is a Rolls-Royce PWR 1 reactor plant and tested Cores A, B and Z before being shut down in 1984. In 1987, the plant was re-commissioned as LAIRD (Loss of Coolant Accident Investigation Rig Dounreay) a non-nuclear test rig, the only one of its kind in the world. LAIRD trials simulated loss of coolant accidents to prove the effectiveness of systems designed to protect the reactor in loss-of-coolant accidents.

Shore Test Facility (STF)

The second reactor, PWR2, is housed in the Shore Test Facility (STF), was commissioned in 1987, and went critical with Core G the same year. The plant was shut down in 1996, and work began to refit the plant with the current core, Core H, in February 1997. This work was completed in 2000 and after two years of safety justification the plant went critical in 2002. Vulcan Trials Operation and Maintenance (VTOM) (the programme under which Core H is tested) was completed and the reactor shut down on 21 July 2015. The reactor will be de-fuelled and examined, and post operational work will continue to 2022. The site would then be decommissioned along with facilities at neighbouring UKAEA Dounreay.[44]

In January 2012 radiation was detected in the reactor's coolant water, caused by a microscopic breach in fuel cladding. This discovery led to HMS Vanguard being scheduled to be refuelled early and contingency measures being applied to other Vanguard and Astute-class submarines, at a cost of £270 million, before similar problems might arise on the submarines. This was not revealed to the public until 2014.[43][47]

See also

- Nuclear power in Scotland

- Atomic Energy Research Establishment

- Nuclear power in the United Kingdom

- Energy policy of the United Kingdom

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- RAF Dounreay

References

- "Dounreay". Collins. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Coventry, Martin (1997) The Castles of Scotland. Goblinshead. ISBN 1-899874-10-0 p.147

- Field, John (1984). Discovering Place Names. Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0852637029.

- McKie, Robin (25 May 2008). "Robots scour sea for atomic waste". The Observer. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- New Scientist, November 1959, article at p.1055

- Frank von Hippel; et al. (February 2010). Fast Breeder Reactor Programs: History and Status (PDF). International Panel on Fissile Materials. pp. 73–88. ISBN 978-0-9819275-6-5. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "Dounreay Fast Reactor celebrates fifty years". Nuclear Engineering International. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2009."Dounreay Fast Reactor celebrates fifty years". Nuclear Engineering International. 10 November 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2009.| archive-url =

- "DFR" (PDF).

- "THE BACKGROUND TO THE DOUNREAY FAST REACTOR" (PDF).

- "New nuclear reactor for Dounreay". BBC. 9 February 1966. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- "Prototype Fast Reactor Timeline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- "Prototype Fast Reactor - PFR" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- "PRIS: Dounreay PFR". IAEA. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "'Reactorsaurus' to rip up station". BBC. 5 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "BBC News - Plan to display parts of Dounreay at London museum". BBC Online. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Edwards, Rob. "Lid blown off Dounreay's lethal secret". NewScientist. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Edwards, Rob. "Scottish nuclear fuel leak 'will never be completely cleaned up'". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Bill Ray (26 January 2016). "Come on kids, let's go play in the abandoned nuclear power station". The Register. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- NDA Strategy - draft for consultation (PDF) (Report). Nuclear Decommissioning Authority. 2005. p. 93. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "DOUNREAY DECOMMISSIONING: Monumental task". The Engineer. 19 May 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015 – via Highbeam Research.

- Ross, John (14 July 2005). "Dounreay chiefs played down major blast at plant". The Scotsman. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Ross, David (25 January 2007). "No-one knows what is left in the Dounreay waste shaft". The Herald. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Ross, David (20 November 2008). "Evidence of many more radioactive particles near beach". The Herald. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "UKAEA advised to close Dounreay beach". Nuclear Engineering International. 24 November 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- "'Most radioactive' particle found on beach near Dounreay". BBC News. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Boss warns of new Dounreay issues". BBC News. 18 September 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- MacDonald, Calum (7 February 2007). "Dounreay nuclear waste was dumped in the sea". The Herald. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- "UKAEA admits to illegal dumping". BBC News. 6 February 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- "Nuclear site operator fined £140k". BBC News. 15 February 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- "BBC News - Nuclear fuel called 'exotics' to leave Dounreay". BBC Online. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Bo Wier (27 February 2013). "Up the chute". Nuclear Engineering International. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Site Closure Programme (Dounreay)" (PDF). Nuclear Decommissioning Authority. 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- "BBC News - Small low-level waste fire at Dounreay reported to Sepa". BBC Online. 13 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Steven Mckenzie (21 November 2014). "Fire at Dounreay led to release of radioactivity". BBC. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Terry Macalister (21 November 2014). "Dounreay nuclear plant fire led to 'unauthorised' radioactivity release". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Leftly, Mark (15 March 2015). "Nuclear waste workers at Dounreay power station fear for their safety". The Independent. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Engineers begin dismantling Dounreay's nuclear core". BBC News. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "UK-US nuclear waste deal to 'help in cancer fight'". BBC News. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- Nuclear (1 April 2016). "UK Government's US nuclear deal denounced as transatlantic". The Hearld. Scotland. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- Grant, Iain. "Workers evacuated from Highland nuclear power station after radioactive contamination discovered".

- Wilson, Dave. "NDA completes transfer of plutonium from Dounreay".

- "Dounreay decommissioning framework contracts awarded - World Nuclear News". www.world-nuclear-news.org.

- "Nuclear submarine to get new core after test reactor problem". BBC. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- Philip Dunne (22 July 2015). "Defence Minister Philip Dunne talks about the shut down of the Vulcan Naval test reactor". Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Rolls-Royce declines to comment on Vulcan future". BBC. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- "Nuclear Liabilities". Hansard. UK Parliament. 24 July 2006. 24 July 2006 : Column 778W. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- David Maddox (8 March 2014). "MoD accused of Dounreay radiation leak cover-up". The Scotsman. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dounreay. |

- Dounreay Site Restoration, official website

- Dounreay - Future Plans, NDA

- Shore Based Testing, Rolls-Royce Marine

- Vulcan leads the way for Navy nuclear reactors, Navy News, 7 January 2003

- Vulcan takes on additional role, Navy News, 4 February 2003

- Dounreay, Scottish Parliament research note, 9 January 2001

- Dounreay - Fast Breeder, Caithness.Org

- The Dounreay Sphere - Design and Construction (video - 25min 11sec), UKAEA, Dounreay TV

- The Building of the Prototype Fast Reactor (video - 23min 44sec), UKAEA, Dounreay TV

- Dounreay Decommissioning Tasks, UKAEA, December 2005

- Dounreay shaft grout to start, Edmund Nuttall, January 2007

- Dounreay Particles Advisory Group: 3rd Report, SEPA, November 2006

- Seabed robot seeks Dounreay pollution, Nuclear Engineering International, 3 October 2007