Doryphoros

The Doryphoros (Greek Δορυφόρος Classical Greek Greek pronunciation: [dorypʰóros], "Spear-Bearer"; Latinised as Doryphorus) of Polykleitos is one of the best known Greek sculptures of classical antiquity, depicting a solidly built, muscular, standing warrior, originally bearing a spear balanced on his left shoulder. Rendered somewhat above life-size, the lost bronze original of the work would have been cast circa 440 BCE,[1] but it is today known only from later (mainly Roman period) marble copies. The work nonetheless forms an important early example of both Classical Greek contrapposto and classical realism; as such, the iconic Doryphoros proved highly influential elsewhere in ancient art.

_-_KAS11.stl.png)

Conception

The renowned Greek sculptor Polykleitos designed a sculptural work as a demonstration of his written treatise, entitled the "Kanon" (or Canon, translated as "measure" or "rule"), exemplifying what he considered to be the perfectly harmonious and balanced proportions of the human body in the sculpted form.

Sometime in the 2nd century CE, the Greek medical writer Galen wrote about the Doryphoros as the perfect visual expression of the Greeks' search for harmony and beauty, which is rendered in the perfectly proportioned sculpted male nude:

Chrysippos holds beauty to consist not in the commensurability or "symmetria" [ie proportions] of the constituent elements [of the body], but in the commensurability of the parts, such as that of finger to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and wrist, and of those to the forearm, and of the forearm to the upper arm, and in fact, of everything to everything else, just as it is written in the Canon of Polyclitus. For having taught us in that work all the proportions of the body, Polyclitus supported his treatise with a work: he made a statue according to the tenets of his treatise, and called the statue, like the work, the 'Canon'.'[2]

Polykleitos is known as the best sculptor of men, with the primary subjects of his works being male athletes with idealized body proportions. He was interested in the mathematical proportions of the human form, which led him to write an essay the Kanon, on the proportions of humans. The Doryphoros is an illustration of his writings in Kanon on the symmetria between the body parts. Polykleitos achieved a balance between muscular tensions and relaxation due to the chiastic principle that he relied on. "Scholars agree that Polykleitos based his calculations on a single module, perhaps the terminal section of the little finger, to determine the corresponding measurements of each body part" (MIA Doryphoros Plaque).

Description

The Doryphoros is a marble copy from Pompeii that dates from 120–50 BCE. The original was made out of bronze in about 440 BCE but is now lost (along with most other bronze sculptures made by a known Greek artist). Neither the original statue nor the treatise have yet been found; it is widely considered that they have not survived from antiquity. Fortunately, several Roman copies in marble—of varying quality and completeness—do survive to convey the essential form of Polykleitos' work.

The sculpture stands at approximately 6 feet 11 inches tall. Polykleitos used distinct proportions when creating this work; for example, the ratio of head to body size is one to seven. The figure's head turned slightly to the right, the heavily-muscled but athletic figure of the Doryphoros is depicted standing in the instant that he steps forward from a static pose. This posture reflects only the slightest incipient movement, and yet the limbs and torso are shown as fully responsive.

The left hand originally held a long spear; the left shoulder (on which the spear originally rested) is depicted as tensed and therefore slightly raised, with the left arm bent and tensed to maintain the spear's position. The figure's pose is classical contrapposto, most obviously seen in the angled positioning of the pelvis. The figure's right leg is straightened, depicted as supporting the body's weight, with the right hip raised and the right torso contracted. The left leg bears no weight and the left hip drops, slightly extending the torso on the left side. The right arm hangs positioned by the figure's side, bearing no load. It is perhaps the earliest extant example of a free-hanging arm in a statue.[3]

In the surviving Roman marble copies, a large sculpted tree stump is obtrusively added behind one leg of the statue in order to support the weight of the stone; this would not have been present in the original bronze (the tensile strength of the metal would have made this unnecessary).[4] A small strut is also usually present to support the right hand and lower arm.[5]

Extant copies

The sculpture was known through the Roman marble replica found in Herculaneum and conserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum, but, according to Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, early connoisseurs such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann passed it by in the royal Bourbon collection at Naples without notable comment.[6] The marble sculpture and a bronze head that had been retrieved at Herculaneum were published in Le Antichità di Ercolano, (1767)[7] but were not identified as representing Polykleitos' Doryphorus until 1863.[8]

For modern eyes, a fragmentary Doryphoros torso in basalt in the Medici collection at the Uffizi "conveys the effect of bronze, and is executed with unusual care", as Kenneth Clark noted, illustrating it in The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form:[9] "It preserves some of the urgency and concentration of the original" lost in the full-size "blockish" marble copies.

Perhaps the best known copy of the Doryphoros was excavated in Pompeii and now resides in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli [Naples, Museo Nazionale 6011].

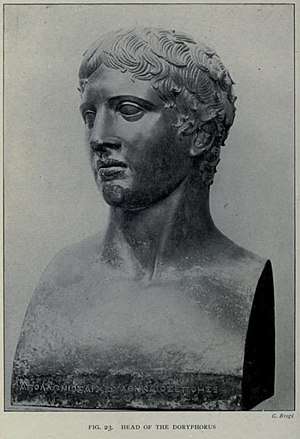

Held in the same museum is a bronze herma of Apollonios [height 0.54 m, Naples, Museo Nazionale 4885], considered by many scholars to be an almost flawless replica of the original Doryphoros head.

Receiving most attention in recent years has been the well-preserved, Roman period copy of the statue in Pentelic marble, purchased in 1986 by the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia). Largely complete with the exception of the lower left arm and fingers of the right hand, the fine copy (height 1.96 m) has been variously dated to the period 120–50 BCE, as well as to the mid-Augustan period. Mia explains that the copy was found in Italian waters during the 1930s and spent several decades in private Italian, Swiss and Canadian collections before resurfacing in the art market around 1980. Italy still claims for the return of the statue due to the fact that it was illegally excavated and exported from Stabia.

Mia’s "The Doryphoros" is in very good condition, especially given the age of the work. All of the breaks in this replica are ancient, except for the left arm. The head has stayed intact. There are some deep scratches on the side and the marks that are on his cheeks and arms are from the roots of plants, which suggest that this copy had been buried for centuries. When it was found, it was in six pieces and has been reassembled. The sculpture has had some minimal restorations, for example "a steel pin has been inserted into the tree trunk that buttresses the right leg, and the sculpture has been reassembled from the six pieces in which it was found: the torso from head to knees, the two calves, the left foot, tree trunk and base, the right foot and base, and the area of the left arm surrounding the bend at the elbow" (Arts Connected). The tip of his nose has been broken off, along with his left forearm and hand, part of the right foot, the penis, and some of the digits of the fingers on the right hand. There is an indentation on his left hip, where the strut that ran to the left forearm has now broken away. There are discolorations and deep striations in the marble on parts of the sculpture that include the arms, legs, torso, and the support stand. More details about Mia's The Doryphoros can be found published on the museum's ArtStories platform.

A copy has been recently found (2012) in the Roman thermae of Baelo Claudia (outside of Tarifa, near the village of Bolonia, in southern Spain).[10][11]

Influence

The Doryphoros was created during the high classical period. During this time, there was an emphasis put on the ideal man who was shown in heroic nudity. The body would be that of a young athlete that included chiseled muscles and a naturalistic pose. The face is generic, displaying no emotion. Some scholars believe that Doryphoros represented a young Achilles, on his way to battle in the Trojan War, while others believe that there is confusion whether the sculpture is meant to depict a mortal or a hero. There have also been discussions on where these sculptures would be located during high classical period, depending on where they were discovered. For example, the copy in Naples was found in the municipal Gymnasium of Pompeii, which leads us to believe that one may have been placed near fitness programs of the youth. Copies were also common for patrons to place in or outside their home.

The canonic proportions of the male torso established by Polykleitos ossified in Hellenistic and Roman times in the heroic cuirass, exemplified by the Augustus of Prima Porta, who wears ceremonial dress armour modelled in relief over an idealised muscular torso which is ostensibly modelled on the Doryphoros.[12] The same depiction has the legs of the emperor arranged in the same manner as the stance of the Doryphoros.

References

- Warren G. Moon, ed. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition, 1995: essays by various scholars resulting from a symposium at the University of Wisconsin, 1989, stimulated by the purchase of the Minneapolis Doryphoros.

- Galen, De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis ("On the doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato") 5.3; noted in Richard Tobin, "The Canon of Polykleitos" American Journal of Archaeology 79.4 (October 1975:307–321) pp308f, with somewhat differing translation.

- Hafner, German (1969). Art of Crete, Mycenae, and Greece. Translated by Bizzarri, Erika. New York: Harry N. Abrams Incorporated. p. 162.

- De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 163. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ḎḤWTY. "Doryphoros: Greek Art Imitating Ideal Form". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- Haskell and Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (Yale University Press), 1981:105.

- Le Antichità di Ercolano vol. V 1767, pp 183–87, considered at the time to be a portrait sculpture of Lucius, son of Agrippa (noted by Haskell and Penny 1981:118 note 10).

- By Carl Friedrichs, in Der Doryphoros des Polyklet, Berlin, 1863.

- Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, 1956, fig 26 p. 69.

- VV. AA.,Una copia del Doríforo en las Termas Marítimas de Baelo Claudia, p.1307, en Actas del XVIII Congreso Internacional de Arqueología Clásica, volumen II, pp.1303-1308, Mérida (2014), ISBN 978-84-606-7949-3.

- Vincenzo Franciosi, Il Doriforo di Pompei (en italiano), p.11, en Pompei/Messene. Il “Doriforo” e il suo contesto, Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa (2013), ISBN 978-88-96055-52-6.

- J.J. Pollini, "The Augustus of Prima Porta and the transformation of the Polykleitan heroic ideal" in Moon 1995:262-81.

- "Polykleitos, Doryphoros". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

Further reading

- Herbert Beck, Peter C. Bol, Maraike Bückling, eds. Polyklet. Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik. Exhibition catalog at the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt am Main. (Von Zabern, Mainz) 1990 ISBN 3-8053-1175-3

- Detlev Kreikenbom: Bildwerke nach Polyklet. Kopienkritische Untersuchungen zu den männlichen statuarischen Typen nach polykletischen Vorbildern. "Diskophoros", Hermes, Doryphoros, Herakles, Diadumenos. Mann, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-7861-1623-7

- Moon, Warren G., ed. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition (University of Wisconsin Press) 1995. Papers from a symposium of 1989 organized round the Minneapolis over-lifesize Doryphoros of Augustan date.

- Greek Ideas & Values: (adapted from The Art of Greece, translated by J.J. Pollitt)