Domenico Dragonetti

Domenico Carlo Maria Dragonetti (7 April 1763 – 16 April 1846) was an Italian double bass virtuoso and composer with a 3 string double bass. He stayed for thirty years in his hometown of Venice, Italy and worked at the Opera Buffa, at the Chapel of San Marco and at the Grand Opera in Vicenza. By that time he had become notable throughout Europe and had turned down several opportunities, including offers from the Tsar of Russia. In 1794, he finally moved to London to play in the orchestra of the King's Theatre, and settled there for the remainder of his life. In fifty years, he became a prominent figure in the musical events of the English capital, performing at the concerts of the Philharmonic Society of London as well as in more private events, where he would meet the most influential persons in the country, like the Prince Consort and the Duke of Leinster. He was acquainted with composers Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven, whom he visited on several occasions in Vienna, and to whom he showed the possibilities of the double bass as a solo instrument. His ability on the instrument also demonstrated the relevance of writing scores for the double bass in the orchestra separate from that of the cello, which was the common rule at the time. He is also remembered today for the Dragonetti bow, which he evolved throughout his life.

Domenico Dragonetti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Domenico Carlo Maria Dragonetti |

| Born | 7 April 1763 Venice, Italy |

| Died | 16 April 1846 (age 83) London, England |

| Genres | Classical |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, double bassist, pedagogue |

| Instruments | Double bass |

| Years active | 1790–1846 |

History

Venice 1763-1794

Dragonetti was born in Venice, Italy of Pietro Dragonetti, a barber and amateur musician, and Caterina Calegari. He began playing the guitar and the double bass by himself on his father's instruments. He was soon noticed by Doretti, a violinist and composer of ball music, who took him along for public performance in Venice. At the age of twelve, he was placed under the tuition of Berini, the best master for the double bass in Venice, who decided after only eleven lessons that he could not teach the boy anything more. At the age of thirteen, Dragonetti was appointed principal player at the Opera Buffa in Venice. At fourteen he was appointed principal double bass player in the Grand Opera Seria at the San Benedetto theatre.

When about eighteen, in Treviso, he was invited to join the quartet of the Tommasini, and was noticed by Morosini, procurator of San Marco, who indulged him in auditioning for the admission in the Chapel of San Marco. He made a first attempt in 1784, which was lost to Antonio Spinelli. He finally joined the institution on 13 September 1787 as the last of the five double bass players of the Chapel with a yearly income of 25 ducats. He soon became the principal bassist. He later was offered a place by the Tsar of Russia, which was declined and got him a salary raise in the Chapel. He became very famous at the time, started playing solo pieces, which was exceptional at the time for the double bass, and even got elected as of the directors of a musical festival held for the coming of fourteen sovereign princes to the republic of Venice. One of his concertos was particularly remarked by the queen of Naples.

When in Vicenza for an engagement at the Grand Opera there, he acquired his famous Gasparo da Salò double bass from the Benedictine Nuns of the Convent of San Pietro (La Pieta) in Vicenza, which is now housed in the museum of St Mark's Basilica. He was offered another position to the Tsar of Russia, which he declined after the procurators of St Mark increased his salary to an exceptional 50 ducats. They even granted him a leave for a year, with a continuation in his wages, to go to the King's Theatre in London. That leave was extended for three more years afterwards, but finally Dragonetti never returned to Venice for more than a brief period during the French occupation of the city, 1805–1814.

Dragonetti had no close family, but had many close friends in the musical world in London. The story that he kept and often traveled with a collection of life-sized cloth mannequins, bringing them to his concerts and having them placed in front row seats of theaters, and even introducing one of these dolls as his wife, is completely unsubstantiated. He was an avid collector, and did indeed collect dolls, sometimes taking one along on trips to amuse the children, of whom he was very fond. He never did learn to speak English, expressing himself in a mixture of Italian, English, French and Venetian dialect, but was an astute businessman, and in fact, helped his surviving family in Venice financially. The authoritative source for information on him is the book of Dr. Fiona Palmer, Domenico Dragonetti in England (1794–1846) pub. Oxford University Press

London 1794-1846

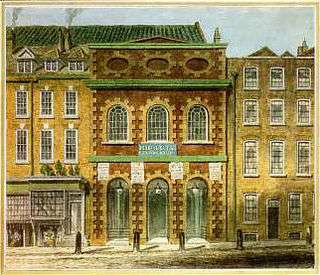

He left Venice on 16 September 1794, partly under the influence of his friend, Giovanni Battista Cimador (who composed a concerto for double bass), and participated in the first rehearsals at the King's Theatre, on 20 October 1794 and finally appeared as orchestra member in the opera Zenobia in Palmira, by Giovanni Paisiello, on 20 December 1794. After only a few months, he became very famous in London, and his brilliant career was to last till the end.

Later he became intimate with the Prince Consort and the Duke of Leinster. He took part between 1816 and 1842, in forty-six concerts held by the Philharmonic Society of London. At the Italian Opera orchestra, he met the cellist Robert Lindley, who became his close friend and with whom he shared the stand during fifty-two years. They made a specialty at playing Arcangelo Corelli's sonatas.

At the age of 82, Dragonetti visited Bonn in August 1845 to participate in the 3-day music festival held as part of the inauguration of the Beethoven Monument there. Various major Beethoven works were conducted by Louis Spohr and Franz Liszt.[1]

He died in his Leicester square lodgings at the age of 83 and was buried on 23 April 1846 in the vaults of the Roman Catholic chapel of St Mary, Moorfields. In 1889 his remains were moved to the Roman Catholic cemetery at Wembley. Vincent Novello and Count Carlo Pepoli (librettist of Vincenzo Bellini's I puritani) were among his most famous friends in London.

Vienna

In 1791–1792, Joseph Haydn accepted a lucrative offer from German impresario Johann Peter Salomon to visit England and conduct new symphonies with large orchestras. The visit was a huge success and generated some of his best known work. Another trip was therefore scheduled in 1794–1795. On that second occasion, Haydn met Dragonetti, who became a very good friend, and who visited him in Vienna in 1799. On that first trip to Vienna, Dragonetti also met Beethoven in a famous encounter.

"Two new and valuable, though but passing acquaintances were made by Beethoven this year, however - with Domenico Dragonetti, the greatest contrabassist known to history, and Johann Baptist Cramer, one of the greatest pianists. Dragonetti was not more remarkable for his astounding execution than for the deep, genuine musical feeling which elevated and ennobled it. He was now - in the spring of 1799, so far as the means are at hand of determining the time - returning to London from a visit to his native city, Venice, and his route took him to Vienna, where he remained several weeks. Beethoven and he soon met and they were mutually pleased with each other. Many years afterwards Dragonetti related the following anecdote to Samuel Appleby, Esq., of Brighton, England: "Beethoven had been told that his new friend could execute violoncello music upon his huge instrument and one morning, when Dragonetti called at his room, he expressed the desire to hear a sonata. The contrabass was sent for, and the Sonata, n°2, of Op.5, was selected. Beethoven played his part, with his eyes immovably fixed upon his companion, and, in the finale, where the arpeggios occur, was so delighted and excited that at the close he sprang up and threw his arms around both player and instrument". The unlucky contrabassists of orchestras had frequent occasions during the next few years to know that this new revelation of the powers and possibilities of their instrument to Beethoven was not forgotten." (Alexander Wheelock Thayer, 1867)

To this day, the mastering of the Beethoven double bass symphonic parts are considered a basic standard for all orchestral double bass players. Dragonetti came back to Vienna for an extensive stay in 1808-1809. On that second trip he became friends with composer Simon Sechter, who would become the court organist in 1824, and professor of composition at the Vienna Conservatorium in 1851. He wrote piano accompaniments to some of his concert pieces, and they maintained a lifelong correspondence. Dragonetti was again in Vienna in 1813 and got to meet once more Beethoven, who had just written Wellington's Victory, to celebrate the victory of Wellington over the French armies of King Joseph Bonaparte at the Battle of Vitoria. The premiere of this work, as well as of Beethoven's seventh symphony was performed on 8 December 1813 in the University's Festsaal, with Dragonetti leading the double basses.

Style

Dragonetti was known for his formidable strength and stamina. It was particularly important at a time when the role of the double bass in the orchestra was to assist the concertmaster in maintaining the cohesion and establishing the tempo. He had huge hands with strong, broad fingers, which allowed him to play with a taller bridge and strings twice as far from the fingerboard as the other bassists.

The physical quality is his huge hand: endowed, first of all, with prodigious strength so that its grip on the strings of the instrument is the equivalent of the grip of a blacksmith's vice... A hand endowed with five fingers so long, big and agile, that all five, including the bent thumb, go up and down the fingerboard each playing a note. (Caffi, 1855)

This was not at all standard in these times, as most players used to play - in one position - one note with the index finger, and one with the other three fingers in combination.

Instruments

Dragonetti was a lover of the fine arts, and a collector of musical instruments as well as many art-related articles, such as original scores and paintings. When he died, the following instruments were dispatched: a giant double bass attributed to Gasparo da Salò and stated to have been used in contemporary performances of Handel's music, which is now conserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; a very fine Domenico Montagnana Basso di Camara (from Venice); a Gasparo da Salò double bass dated 1590; an Amati double bass; a Maggini double bass; a Stradivarius violin (once played by Paganini), now known as the "Dragonetti"; a Guarnerius "del Gesù" violin dated 1742, now known as the "Dragonetti-Walton"; a Gasparo da Salò violin; two Amati violins; one Lafont violin; a Stradivarius violin copy; 26 unnamed violins; a Gasparo da Salò viola; an Amati viola; a Hill viola; 5 unnamed violas; 6 cellos; a large cello; 3 guitars; 2 bassoons; 3 French horns.

Mention is made of this on The Contrabass Shoppe web site which says...

"There are various stories of how Dragonetti came into possession of the famous Gasparo da Salo bass.[2] The fascinating and highly commendable biography Domenico Dragonetti In England by Fiona M. Palmer (Clarendon Press Oxford 1997) seems to offer the most plausible account. Because of Dragonetti's unprecedented virtuosity as a soloist, attractive offers of work were made from both London and Moscow. As remuneration for renouncing the offers and remaining as principal bassist with the orchestra of the Ducal Chapel of St Mark's in Venice (an orchestra of considerable importance), a decree made in 1791 gave Dragonetti a financial gratuity.

Similarly, it is reputed that Dragonetti was presented with an instrument made by Gasparo da Salo (1542–1609) by the Benedictine nuns who occupied St Peter's monastery in Vicenza where Dragonetti lived and played in the Grand Opera. In the Palmer biography, a footnote refers to a 1906 account by C.P.A. Berenzi, who suggests that the instrument may have been made for the monks of St Peter's, Vicenza, by Gasparo da Salo, and acquired by the procurators of St Mark's to entice Dragonetti to remain in their employ."

Compositions

When he left for London in 1795, Dragonetti left many papers and manuscripts, including a Complete system of the double bass, or instruction book for that instrument, containing many elaborate exercises and studies, in the care of a friend. Unfortunately, they were sold and could not be retrieved by their author when he returned to Venice after some years. Today, many of his letters, personal papers, compositions, solos and manuscripts are to be found in the British Library. Some were directly bequeathed by Dragonetti, some were offered by Vincent Novello, and some were bought at auctions. Some of the compositions by Dragonetti include

- Adagio and Rondo in A major, for double bass and orchestra;

- Andante and Rondo, for double bass and strings;

- Concerto no. 5 in A major, for double bass and orchestra;

- Grande Alegro for Double bass and strings. There also exists an arrangement of Grande Allegro for double bass and piano by Simon Sechter (1788–1867) in British Museum, London (Add,17726)

- Menuet and Alegro for double bass and piano;

- Opera for double bass and piano;

- Sonata for double bass and piano;

- Allegretto for double bass and piano;

- Famous solo in E minor for double bass and piano;

- Adagio and Rondo in C major for double bass and piano;

- Concerto in G major (Andante, Alegretto) for double bass and orchestra

- Serenata, for piano and string bass

- Solo in D major, for double bass and piano

- Pezzo Di Concerto

- Twelve Waltzes for solo double bass

Also

- Concerto in A major for string bass and orchestra. "Ever since the publication by Leduc (1925) of [the concerto in A major] there has been a question concerning its true authorship. It is now generally believed that it is the work of Edouard Nanny who created it as a tribute to Dragonetti."[3]

References

- Alessandra Comini, The Changing Image of Beethoven: A Study in Mythmaking

- Pio, Stefano (2002). Liuteri & Sonadori, Venice 1750 -1870. Venice, Italy: Venice research. pp. 27–38. ISBN 9788890725210. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Dragonetti, Domenico. Concerto for double bass and piano. David Walter, ed. USA: Liben Publishers, 2000, piano score p. [2].

- Berenzi, Angelo (1906). Di alcuni stumenti fabbricati da Gasparo di Salò posseduti da Ole Bull, da Dragonetti e dalle sorelle Milanollo (in Italian). Brescia: Geroldi. OCLC 54196638.

- Brun, Paul (2000). A new history of the double bass. Paul Brun Productions. pp. 240–254. ISBN 2-9514461-0-1.

- Caffi, Francesco (1987). Elvidio Surian (ed.). Storia della musica sacra nella già Cappella ducale di S. Marco in Venezia dal 1318 al 1797 (in Italian). Firenze. ISBN 88-222-3479-0.

- Heyes, David (Spring–Summer 1996). "The Dragon's Allure--the lasting legacy of Dragonetti". Double Bassist. 1: 42. ISSN 1362-0835.

- Palmer, Fiona M. (1997). Domenico Dragonetti in England (1794-1846) : the career of a double bass virtuoso. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-816591-9.

- Slatford, Rodney (1970). "Domenico Dragonetti". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 97: 21. doi:10.1093/jrma/97.1.21.

- Thayer, Alexander Wheelock (1967). Elliot Forbes (ed.). Thayer’s life of Beethoven. Princeton University Press. p. 208. OCLC 2898890.

External links

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1888). . Dictionary of National Biography. 15. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Free scores by Domenico Dragonetti at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)