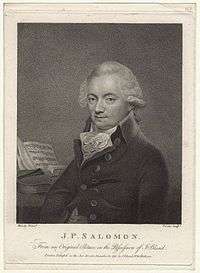

Johann Peter Salomon

Johann Peter Salomon (20 February 1745 [baptized] – 28 November 1815) was a German violinist, composer, conductor and musical impresario. Although he was an accomplished violinist, he is best known for bringing Joseph Haydn to London and for conducting the symphonies that Haydn wrote during his stay in England.

Life

He was born in Bonn and was the second son of Philipp Salomon, an oboist at the court in Bonn. His birth home was at Bonngasse 515, coincidentally the later birth home of Beethoven.[1] At the age of thirteen, he became a violinist in the court orchestra and six years later became the concert master of the orchestra of Prince Heinrich of Prussia. He composed several works for the court, including four operas and an oratorio. He moved to London in the early 1780s, where he worked as a composer and played violin both as a celebrated soloist and in a string quartet. He made his first public appearance at Covent Garden on 23 March 1781.

While in England, Salomon composed two operas for the Royal Opera,[2] several art songs, a number of concertos, and chamber music pieces. He is perhaps best known today, however, as a concert organiser and conductor.

Salomon brought Joseph Haydn to London in 1791–92 and 1794–95, and together with Haydn led the first performances of many of the works that Haydn composed while in England.[3] Haydn wrote his symphonies numbers 93 to 104 for these trips, which are sometimes known as the Salomon symphonies (they are more widely known as the London symphonies). Haydn's esteem for his impresario and orchestral leader can sometimes be seen in the symphonies: for example, the cadenza in the slow movement of the 96th and the phrase marked Salomon solo ma piano in the trio of the 97th; the Sinfonia Concertante in B-flat major was composed for Salomon, who played the solo violin part; and the six string quartets opp. 71 and 74, written between the two London visits in 1793, though dedicated to Count Apponyi, were clearly designed for the public performances that Salomon's quartet gave in London. Salomon is also said to have had a hand in providing Haydn with the original model for the text of The Creation. He was one of the founder-members of the Philharmonic Society and led the orchestra at its first concert on 8 March 1813.

Salomon is also believed to have given the Jupiter nickname to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Symphony No. 41.[4] Amongst his protégés was the English composer and soloist George Pinto.

Salomon died in London in 1815, of injuries suffered when he was thrown from his horse.[5] He is buried in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey.

Assessment

Salomon's violin playing was highly regarded in his day; for a collection of reviews, see Robbins Landon (1976, 24–27). Robbins Landon also praises his personal qualities: "Salomon was not only a clever and sensitive impresario, he was also generous, scrupulously honest, and very efficient in business matters."[6] Beethoven, who knew Salomon from his days in Bonn, wrote to Ries on hearing of his death, "Salomon's death grieves me much, for he was a noble man, and I remember him since I was a child."[5]

Since 2011 the Royal Philharmonic Society has awarded the Salomon Prize to highlight talent and dedication within UK orchestras.[7]

Notes

- Robbins Landon (1976, 24)

- Of his 1795 opera Windsor Castle, Joseph Haydn wrote "ganz passabel"; "quite passable". Haydn wrote an overture for the opera (Robbins Landon 1976: 24, 483).

- At the performances, both Haydn and Salomon were seated center stage. Haydn (who according to Burney "presided" seated at a piano while Salomon led with his violin, a common practice of the time. The tempos were set by Salomon. See Robbins Landon (1976: 52, 56–57).

- Heartz, Daniel, Mozart, Haydn and Early Beethoven 1781–1802, p. 210, Norton (2009), ISBN 978-0-393-06634-0

- Robbins Landon (1976, 27)

- Robbins Landon (1976, 24–27)

- "The Salomon Prize". Royal Philharmonic Society. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014.

References

- Hubert Unverricht. The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie (1992), ISBN 0-333-73432-7 and ISBN 1-56159-228-5

- The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, by John Warrack and Ewan West (1992), ISBN 0-19-869164-5

- Robbins Landon, H. C. (1976) Haydn: Chronicle and Works. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.