Discouraged worker

In economics, a discouraged worker is a person of legal employment age who is not actively seeking employment or who has not found employment after long-term unemployment, but who would prefer to be working. This is usually because an individual has given up looking, hence the term "discouraged".

A discouraged worker, since not actively seeking employment, has fallen out of the core statistics of the unemployment rate since he is neither working nor job-seeking. Their giving up on job-seeking may derive from a variety of factors including a shortage of jobs in their locality or line of work; discrimination for reasons such as age, race, sex, religion, sexual orientation, and disability; a lack of necessary skills, training, or experience; a chronic illness or disability; or simply a lack of success in finding a job.[1]

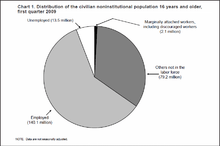

As a general practice, discouraged workers, who are often classified as marginally attached to the labor force, on the margins of the labor force, or as part of hidden unemployment, are not considered part of the labor force, and are thus not counted in most official unemployment rates—which influences the appearance and interpretation of unemployment statistics. Although some countries offer alternative measures of unemployment rate, the existence of discouraged workers can be inferred from a low employment-to-population ratio.

United States

In the United States, a discouraged worker is defined as a person not in the labor force who wants and is available for a job and who has looked for work sometime in the past 12 months (or since the end of his or her last job if a job was held within the past 12 months), but who is not currently looking because of real or perceived poor employment prospects.[2][3][4]

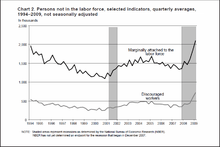

The Bureau of Labor Statistics does not count discouraged workers as unemployed but rather refers to them as only "marginally attached to the labor force".[5][6][7] This means that the officially measured unemployment captures so-called "frictional unemployment" and not much else.[8] This has led some economists to believe that the actual unemployment rate in the United States is higher than what is officially reported while others suggest that discouraged workers voluntarily choose not to work.[9] Nonetheless, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has published the discouraged worker rate in alternative measures of labor underutilization under U-4 since 1994 when the most recent redesign of the CPS was implemented.[10][11]

The United States Department of Labor first began tracking discouraged workers in 1967 and found 500,000 at the time.[12] Today, In the United States, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics as of April 2009, there are 740,000 discouraged workers.[13][14] There is an ongoing debate as to whether discouraged workers should be included in the official unemployment rate.[12] Over time, it has been shown that a disproportionate number of young people, blacks, Hispanics, and men make up discouraged workers.[15][16] Nonetheless, it is generally believed that the discouraged worker is underestimated because it does not include homeless people or those who have not looked for or held a job during the past twelve months and is often poorly tracked.[12][17]

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the top five reasons for discouragement are the following:[18]

- The worker thinks no work is available.

- The worker could not find work.

- The worker lacks schooling or training.

- The worker is viewed as too young or too old by the prospective employer.

- The worker is the target of various types of discrimination.

Canada

In Canada, discouraged workers are often referred to as hidden unemployed because of their behavioral pattern, and are often described as on the margins of the labour force.[19] Since the numbers of discouraged workers and of unemployed generally move in the same direction during the business cycle and the seasons (both tend to rise in periods of low economic activity and vice versa), some economists have suggested that discouraged workers should be included in the unemployment numbers because of the close association.[19]

The information on the number and composition of the discouraged worker group in Canada originates from two main sources. One source is the monthly Labour Force Survey (LFS), which identifies persons who looked for work in the past six months but who have since stopped searching. The other source is the Survey of Job Opportunities (SJO), which is much closer in design to the approach used in many other countries. In this survey, all those expressing a desire for work and who are available for work are counted, irrespective of their past job search activity.[19]

In Canada, while discouraged workers were once less educated than "average workers", they now have better training and education but still tend to be concentrated in areas of high unemployment.[1][19] Discouraged workers are not seeking a job for one of two reasons: labour market-related reasons (worker discouragement, waiting for recall to a former job or waiting for replies to earlier job search efforts) and personal and other reasons (illness or disability, personal or family responsibilities, going to school, and so on).[1]

European Union

Unemployment statistics published according to the ILO methodology may understate actual unemployment in the economy.[20] The EU statistical bureau EUROSTAT started publishing figures on discouraged workers in 2010.[21] According to the method used by EUROSTAT there are 3 categories that make up discouraged workers;

- underemployed part-time workers

- jobless persons seeking a job but not immediately available for work,

- persons available for work but not seeking it

The first group are contained in the employed statistics of the European Labour Force Survey while the second two are contained in the inactive persons statistics of that survey. In 2012 there were 9.2 million underemployed part-time workers, 2.3 million jobless persons seeking a job but not immediately available for work, and 8.9 million persons available for work but not seeking it, an increase of 0.6 million for underemployed and 0.3 million for the two groups making up discouraged workers.[22]

If the discouraged workers and underemployed are added to official unemployed statistics Spain has the highest number real unemployed (8.4 Million), followed by Italy (6.4 Million), United Kingdom (5.5 Million), France (4.8 Million) and Germany (3.6 Million).

| Country | Underemployed Part-time workers Thousands |

Jobless persons seeking a job but not immediately available for work Thousands |

Persons available for work but not seeking it Thousands |

Unemployed Thousands |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 158 | 100 | 60 | 369 | |

| 29 | 270 | 26 | 410 | |

| 27 | 62 | 17 | 367 | |

| 88 | 69 | 24 | 219 | |

| 1,810 | 582 | 508 | 2,316 | |

| 10 | 41 | 3 | 71 | |

| 147 | 44 | 13 | 316 | |

| 190 | 91 | 36 | 1,204 | |

| 1,385 | 1,071 | 236 | 5,769 | |

| 1,144 | 285 | 444 | 3,002 | |

| 605 | 2,975 | 111 | 2,744 | |

| 20 | 15 | 3 | 52 | |

| 44 | 67 | 6 | 155 | |

| 37 | 16 | 197 | ||

| 5 | 13 | 2 | 13 | |

| 88 | 215 | 11 | 476 | |

| 5 | 5 | 12 | ||

| 138 | 308 | 85 | 469 | |

| 148 | 144 | 39 | 189 | |

| 344 | 632 | 102 | 1,749 | |

| 256 | 232 | 29 | 860 | |

| 239 | 458 | 701 | ||

| 18 | 13 | 90 | ||

| 37 | 41 | 13 | 378 | |

| 75 | 111 | 63 | 207 | |

| 237 | 134 | 101 | 403 | |

| 1,907 | 774 | 334 | 2,511 | |

| 81 | 67 | 22 | 85 | |

See also

- Involuntary unemployment

- NEET

- Labor force

- Unemployment rate

- Workforce

- Types of unemployment

United States

Canada

- Labour and Household Surveys Analysis Division of Statistics Canada

References

- Akyeampong, Ernest B. (Autumn 1992 (). "Discouraged workers - where have they gone?" (PDF). Perspectives on Labour and Income. 3. Canada: Statistics Canada. 4 (Article 5). Catalogue=75- 001E. Retrieved 2009-05-12. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003) [January 2002]. Economics: Principles in Action. The Wall Street Journal: Classroom Edition (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall: Addison Wesley Longman. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-13-063085-8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "BLS Information". Glossary. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services. February 28, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- "Glossary". Congressional Budget Office. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- Castillo, Monica D. (July 1998). "Persons outside the labor force who want a job" (PDF). Monthly Labor Review. LABSTAT Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Hederman Jr., Rea S. (January 9, 2004). "Tracking the Long-Term Unemployed and Discouraged Workers". WebMemo #389. The heritage foundation. Archived from the original on June 9, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- Rampell, Catherine (April 30, 2009). "Job Market Pie". Business: Economicx. The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- Garrison, Roger (July 12, 2004). "The Sin of Wages?". Archives. Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Zuckerman, Sam (November 17, 2002). "Jobless statistics overlook many Official numbers omit discouraged seekers, part-time workers". Business. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- "Alternative measures of labor underutilization". Economic News Release. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Current Employment Statistics. May 8, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- "The Unemployment Rate and Beyond: Alternative Measures of Labor Underutilization (Issues in Labor Statistics, Summary 08-06, June 2008)" (PDF). Issues in labor statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. June 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- McCARROLL, THOMAS (Sep 9, 1991). "Down And Out: "Discouraged" Workers". magazine. Time magazine. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- "Black Male Unemployment Jumps to 17.2%". Dollars & Sense. May 8, 2009. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- "Employment Situation Summary". Economic News Release. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Labor Force Statistics. May 8, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- "Issues in Labor Statistics: Ranks of Discouraged Workers and Others Marginally Attached to the Labor Force Rise During Recession" (PDF). Issues in Labor Statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services. May 1, 2009. p. 2. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- Ahrens, Frank (May 8, 2009). "Actual U.S. Unemployment: 15.8%". Economy Watch. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- PODSADA, JANICE (April 19, 2009). "'Hidden Unemployment' Inflates State's Real Jobless Figures". Business. The Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- "Ranks of Discouraged Workers and Others Marginally Attached to the Labor Force Rise During Recession" (PDF). Issues in Labor Statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. April 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- Akyeampong, Ernest B. (Autumn 1989). "Discouraged Workers" (PDF). Perspectives on Labour and Income. 2. Canada: Statistics Canada. 1. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- "10 things you didn't know about the unemployment statistics". the Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2013-11-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Unemployment and beyond". Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-28. Retrieved 2013-11-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Akyeampong, Ernest B. "Persons on the Margins of the Labour Force," The Labour Force (71-001). Statistics Canada, April 1987.

- Akyeampong, Ernest B. "Women Wanting Work But Not Looking Due to Child Care Demands," The Labour Force. April 1988.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Persons in the Labour Force, Australia (Including Persons who Wanted Work but who were not Defined as Unemployed) (6219.0). July 1985.

- Jackson, George. "Alternative Concepts and Measures of Unemployment," The Labour Force. February 1987.

- Macredie, Ian. "Persons Not in the Labour Force: Job Search Activities and the Desire for Employment, September 1984," The Labour Force. October 1984.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Employment Outlook. September 1987. Akyeampong, E.B. "Discouraged workers." Perspectives on labour and income, Quarterly, Catalogue 75-001E, Autumn 1989. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, pp. 64–69.

- "Women wanting work, but not looking due to child care demands." The labour force, Monthly, Catalogue 71-001, April 1988. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, pp. 123–131.

- "Persons on the margins of the labour force." The labour force, Monthly, Catalogue 71-001, April 1987. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, pp. 85–131.

- Frenken, H. "The pension carrot: incentives to early retirement." Perspectives on labour and income, Quarterly, Catalogue 75-001E, Autumn 1991. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, pp. 18–27.

- Jackson, G. "Alternative concepts and measures of unemployment." The labour force, Monthly, Catalogue 71-001, February 1987. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, pp. 85–120.

- Macredie, I. "Persons not in the labour force - job search activities and the desire for employment, September 1984." The labour force, Monthly, Catalogue 71-001, October 1984. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, pp. 91–104.

Further reading

- Blundell, Richard; J. Ham; Costas Meghir (Jan 1998). "Unemployment, discouraged workers and female labour supply". Research in Economics. 52 (2): 103–131. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.638.3829. doi:10.1006/reec.1997.0158.

- Hussmanns, Ralf; Farhad Mehran; Vijaya Varmā (1990). Surveys of economically active population, employment, unemployment, and underemployment: an ILO manual on concepts and methods. illustrated. International Labour Office (2 ed.). International Labour Organization. ISBN 978-92-2-106516-6.

External links

- Discouraged workers, OECD Stats extract

- Incidence of discouraged workers, OECD

United States

- Discouraged workers in glossary, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services

- Employment Situation Summary, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services

- Alternative measures of labor underutilization, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services

- Discouraged Worker, Investopedia

- Down And Out: "Discouraged" Workers, Time magazine

- Actual U.S. Unemployment: 15.8%, The Washington Post

- 'Hidden Unemployment' Inflates State's Real Jobless Figures, The Hartford Courant

- Tracking the Long-Term Unemployed and Discouraged Workers, The Heritage Foundation

- Ranks of Discouraged Workers and Others Marginally Attached to the Labor Force Rise During Recession Issues in Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Information Services

- Discouraged Workers, Drexel

- Jobless statistics overlook many, San Francisco Chronicle

- PROMOTING ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY AND OWNERSHIP

- Labor force characteristics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey