Diadema setosum

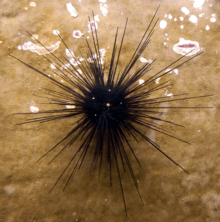

Diadema setosum is a species of long-spined sea urchin belonging to the family Diadematidae. It is a typical sea urchin, with extremely long, hollow spines that are mildly venomous. D. setosum differs from other Diadema with five, characteristic white dots that can be found on its body. The species can be found throughout the Indo-Pacific region, from Australia and Africa to Japan and the Red Sea. Despite being capable of causing painful stings when stepped upon, the urchin is only slightly venomous and does not pose a serious threat to humans.

| Black long spine urchin | |

|---|---|

| Diadema setosum in Oman. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | D. setosum |

| Binomial name | |

| Diadema setosum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Description

As a member of the class Echinoidea, the anatomy of Diadema setosum is that of a typical sea urchin. All of the animal's internal organs are enclosed within the spherical, black test that is essentially the body of the organism. However, the body is not perfectly spherical – Diadema tests are slightly dorso-ventrally compressed. Protruding outwards from the central body are the long spines iconic of a sea urchin's appearance. Like the other members of the family Diadematidae, the spines of D. setosum are extremely long and narrow in proportion to its body. The spines, often black but sometimes brown-banded, are hollow and contain a mild venom. D. setosum can be distinguished from other species in the genus Diadema by the presence of five white spots on the animal's test, strategically located between the urchin's ambulacral grooves.

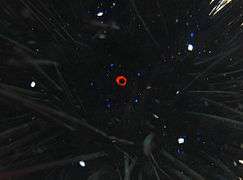

In addition, a clear distinguishing characteristic of the species is the presence of a bright, orange ring around the urchin's periproctal cone, a structure commonly referred to as the urchin's "anus". A few other minor characteristics in D. setosum include bluish spots on the organism's genital plates and similar blue spots (iridophores) arranged in linear fashion along its test. An apical ring is absent in the species, along with calcareous platelets on its apical cone.[2][3] Sexually mature Diadema setosum specimens average from 35 to 80 grams in weight.[4] Adults average a size of no more than 70 millimeters in test diameter and around 40 millimeters high.[5]

.jpg) General look

General look Detail of the anal papilla.

Detail of the anal papilla. Close-up on the classical characteristics : orange ring, five white spots, blue iridophores.

Close-up on the classical characteristics : orange ring, five white spots, blue iridophores. Specimen with white spines.

Specimen with white spines.

Distribution and habitat

Diadema setosum is a widely distributed species of sea urchin. Its range stretches throughout the Indo-Pacific basin, longitudinally from the Red Sea and then eastward to the Australian coast. Latitudinally, the species can be found as far north as Japan and its range extends as far south as the southern tip of the African east coast.[2]

The species has been introduced into other localities not within its natural range. In 2006, two living specimens of Diadema setosum were found in waters off the Kaş peninsula in Turkey. The discovery and subsequent collection of these individuals makes D. setosum the first invasive Erythrean sea urchin in the Mediterranean.[2] Several hypotheses have been proposed for the finding of these individuals. Larvae of the species may have traveled through the Suez Canal (Lessepsian migration) into the Mediterranean from the Gulf of Suez, where the species has a thriving natural population. Another proposed vector is that of foreign ships bringing in individuals via their ballasts. A final possibility proposed was that the individual specimens were intentionally released by aquarists.[2]

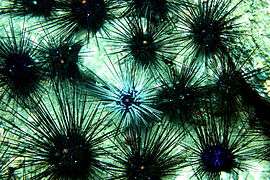

Diadema setosum is commonly associated with coral reefs, but is also found on sand flats and in seagrass beds. Along with the other members of the family, D. setosum is a prolific grazer. They are known to feed on a variety of algal species common on tropical coral reefs. The ecological importance of the taxon as a whole has been stressed because of its herbivorous habits.[5]

In Hong Kong, Diadema setosum is omnipresent in rocky reefs, with a population density of up to one individual per 3.4m2. The unusually large number of these urchins is theorised to be partly natural, and partly due to overfishing of its primary predator in the region, the blackspot tuskfish (Cheorodon schoenleinii).[6]

Biology

The species has been known to spawn both seasonally and year-round depending on the location of the spawning population. It has been suggested that Diadema setosum populations are temperature-dependent in their spawning seasonalities. Temperatures higher than 25 °C (77 °F) have been cited as a possible spawning cue.[7] Equatorial populations are those recorded to spawn at no particular times throughout the entire year. This is true for the Philippine populations of D. setosum.[8] For a population in the Persian Gulf, spawning occurs during the months of April to May.[4] Other cues, such as the phases of the moon have been observed to affect the spawning of D. setosum populations. The species has been found to trigger spawning events in concordance with the appearance of a full moon.[9]

Evolutionarily, Diadema setosum is considered one of the oldest of the known extant species in the genus Diadema. Genetic analysis of the Diadema have placed D. setosum at a basal branch on a cladogram, having it as the sister group to all the other remaining members of the genus.[10] Morphological analysis confirms this conclusion, adding weight to the concept of D. setosum being the most basal of the Diadema and possibly the oldest extant species in the genus.[5]

Like other venomous sea urchins, the venom of Diadema setosum is only mild and not at all fatal to humans. The toxin mostly causes swelling and pain, and gradually diffuses over several hours. More danger is presented by the delivery system – the urchin's spines which are extremely brittle and needle-like. They easily break off within flesh and are quite a challenge to extract.[11]

In terms of behavior, D. setosum has been observed to be able to avoid danger by rapidly inverting its body and "running" on the tips of its longest spines. This behavior is triggered by sudden impacts and the snapping of one or more of its spines. During the process, upon encountering small obstacles, D. setosum will take on a rolling motion much like the robot from the Interstellar movie. It has been observed to move 30 inches in just 7 seconds using this method of locomotion.

It is also worth noting that this particular variety has some of the very best vision observed among sea urchins and will regularly redirect spines toward passing fish as a defense mechanism. Although unclear, this vision seems to be achieved by the sensing of light that enters each spine and it transmitted down the spines shaft and sensed at the base, although further scientific research is required.

Gallery

From Zanzibar

From Zanzibar From la Réunion

From la Réunion- A specimen encountered in Kenya. The 5-fold symmetry is obvious.

D. setosum along with Diadema savignyi : test shape, spines length and orange ring help telling them apart.

D. setosum along with Diadema savignyi : test shape, spines length and orange ring help telling them apart. A classical specimen with long, black spines. The characteristic orange ring is visible in the photo.

A classical specimen with long, black spines. The characteristic orange ring is visible in the photo.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diadema setosum. |

- Alsaffar, Adel H.; Khalid P. Lone (2000). "Reproductive cycles of Diadema setosum and Echinometra mathaei (Echinoidea: Echinodermata) from Kuwait (Northern Arabian Gulf)". Bulletin of Marine Science. 67 (2): 845–856.

References

- Kroh, Andreas (2013). Kroh A, Mooi R (eds.). "Diadema setosum (Leske, 1778)". World Echinoidea Database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2013-11-22.

- Yokes, Baki; Bella S. Galil (2006). "The first record of the needle-spined urchin Diadema setosum (Leske, 1778) (Echinodermata: Echinoidea: Diadematidae) from the Mediterranean Sea". Aquatic Invasions. 1 (3): 188–190. doi:10.3391/ai.2006.1.3.15.

- Clark, HL (1925). A catalogue of the recent sea-urchins (Echinoidea) in the collection of the British Museum (Natural History). London: British Museum. p. 250.

- Alsaffar, Adel H.; Khalid P. Lone (2000). "Reproductive cycles of Diadema setosum and Echinometra mathaei (Echinoidea: Echinodermata) from Kuwait (Northern Arabian Gulf)". Bulletin of Marine Science. 67 (2): 845–856.

- Coppard, Simon Edward; Andrew C. Campbell (2006). "Taxonomic significance of test morphology in the echinoid genera Diadema Gray, 1825 and Echinothrix Peters, 1853 (Echinodermata)" (PDF). Zoosystema. 28 (1): 93–112. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-11-27. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- "Diadema sea urchins and the Black-spot tuskfish".

- Pearse, John S. (1974). "Reproductive patterns of tropical reef animals: three species of sea urchins". Proceedings of the 2nd International Coral Reef Symposium. Brisbane, Australia: ICRS. 1: 235–240. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- Tuason, A. Y.; Ed D. Gomez (1979). "The reproductive biology of Tripneustes gratilla Linnaeus (Echinodermata: Echinoidea), with some notes on Diadema setosum". Proceedings of the International Symposium on Marine Biogeographic Evolution. Auckland, New Zealand. 2: 707–716.

- Lessios, H. A. (1981). "Reproductive periodicity of the echinoids Diadema and Echinometra on the two coasts of Panama". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 50 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(81)90062-9.

- Lessios, H. A.; B. D. Kessing; John S. Pearse (2001). "Population structure and speciation in tropical seas: Global phylogeography of the sea urchin Diadema". Evolution. 55 (5): 955–975. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2001)055[0955:PSASIT]2.0.CO;2. PMID 11430656.

- Williamson, JA; PJ Fenner; JW Burnett; JF Rifkin (1996). Venomous and poisonous marine animals: a medical and biological handbook. Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales Press. p. 504. ISBN 0-86840-279-6.

External links

- Photos of Diadema setosum on Sealife Collection