Deathbed conversion

A deathbed conversion is the adoption of a particular religious faith shortly before dying. Making a conversion on one's deathbed may reflect an immediate change of belief, a desire to formalize longer-term beliefs, or a desire to complete a process of conversion already underway. Claims of the deathbed conversion of famous or influential figures have also been used in history as rhetorical devices.

.jpg)

Overview

Conversions at the point of death have a long history. The first recorded deathbed conversion appears in the Gospel of Luke where the good thief, crucified beside Jesus, expresses belief in Christ. Jesus accepts his conversion, saying “Today you shall be with Me in Paradise".

Perhaps the most momentous conversion in Western history was that of Constantine I, Roman Emperor and later proclaimed a Christian Saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church. While his belief in Christianity occurred long before his death, it was only on his deathbed that he was baptised, in 337 by the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia,[1][2] While traditional sources disagree as to why this happened so late, modern historiography concludes that Constantine chose religious tolerance as an instrument to bolster his reign. According to Bart Ehrman, all Christians contemporary to Constantine got baptized on their deathbed since they firmly believed that continuing to sin after baptism ensures their eternal damnation.[3] Ehrman sees no conflict between Constantine's Paganism and him being a Christian.[3]

Notable deathbed conversions

King Charles II

Charles II of England reigned in an Anglican nation at a time of strong religious conflict. Though his sympathies were at least somewhat with the Roman Catholic faith, he ruled as an Anglican, though he attempted to lessen the persecution and legal penalties affecting non-Anglicans in England, notably through the Royal Declaration of Indulgence. As he lay dying following a stroke, released of the political need, he was received into the Catholic Church.[4]

Jean de La Fontaine

The most famous French fabulist published a revised edition of his greatest work, Contes, in 1692, the same year that he began to suffer a severe illness. Under such circumstances, Jean de La Fontaine turned to religion.[5] A young priest, M. Poucet, tried to persuade him about the impropriety of the Contes, and it is said that the destruction of a new play of some merit was demanded and submitted to as a proof of repentance. La Fontaine received the Viaticum, and the following years, he continued to write poems and fables.[6] He died in 1695.

Sir Allan Napier MacNab

Sir Allan Napier MacNab, Canadian political leader, died 8 August 1862 in Hamilton, Ontario. His deathbed conversion to Catholicism caused a furor in the press in the following days. The Toronto Globe and the Hamilton Spectator expressed strong doubts about the conversion, and the Anglican rector of Christ Church in Hamilton declared that MacNab died a Protestant.[7] MacNab's Catholic baptism is recorded at St. Mary's Cathedral in Hamilton, performed by John, Bishop of Hamilton, on 7 August 1862. Lending credibility to this conversion, MacNab's second wife, who predeceased him, was Catholic, and their two daughters were raised as Catholics.[8]

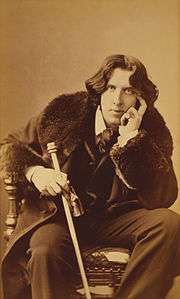

Oscar Wilde

Author and wit Oscar Wilde converted to Catholicism during his final illness.[9][10][11][12] Robert Ross gave a clear and unambiguous account: ‘When I went for the priest to come to his death-bed he was quite conscious and raised his hand in response to questions and satisfied the priest, Father Cuthbert Dunne of the Passionists. It was the morning before he died and for about three hours he understood what was going on (and knew I had come from the South in response to a telegram) that he was given the last sacrament.[13] The Passionist house in Avenue Hoche, has a house journal which contains a record, written by Dunne, of his having received Wilde into full communion with the Church. While Wilde's conversion may have come as a surprise, he had long maintained an interest in the Catholic Church, having met with Pope Pius IX in 1877 and describing the Roman Catholic Church as "for saints and sinners alone – for respectable people, the Anglican Church will do". However, how much of a believer in all the tenets of Catholicism Wilde ever was is arguable: in particular, against Ross's insistence on the truth of Catholicism: "No, Robbie, it isn't true."[14][15][16] "My position is curious," Wilde epigrammatised, "I am not a Catholic: I am simply a violent Papist."[17]

In his poem Ballad of Reading Gaol, Wilde wrote:

Ah! Happy they whose hearts can break

And peace of pardon win!

How else may man make straight his plan

And cleanse his soul from Sin?

How else but through a broken heart

May Lord Christ enter in?

Wallace Stevens

The poet Wallace Stevens is said to have been baptized a Catholic during his last days suffering from stomach cancer.[18] This account is disputed, particularly by Stevens's daughter, Holly,[19] and critic, Helen Vendler, who, in a letter to James Wm. Chichetto, thought Fr. Arthur Hanley was "forgetful" since "he was interviewed twenty years after Stevens' death."

Spurious deathbed conversions

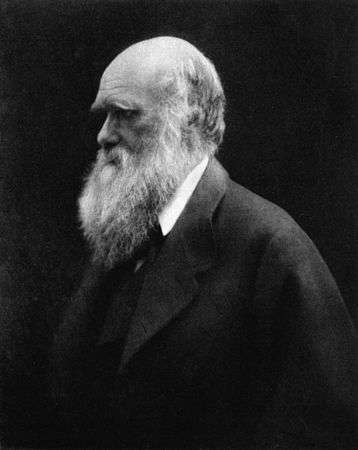

Charles Darwin

One famous example is Charles Darwin's deathbed conversion in which it was claimed by Lady Hope that Darwin said: "How I wish I had not expressed my theory of evolution as I have done." He went on to say that he would like her to gather a congregation since he "would like to speak to them of Christ Jesus and His salvation, being in a state where he was eagerly savoring the heavenly anticipation of bliss."[20] Lady Hope's story was printed in the Boston Watchman Examiner. The story spread, and the claims were republished as late as October 1955 in the Reformation Review and in the Monthly Record of the Free Church of Scotland in February 1957.

Lady Hope's story is not supported by Darwin's children. Darwin's son Francis Darwin accused her of lying, saying that "Lady Hope's account of my father's views on religion is quite untrue. I have publicly accused her of falsehood, but have not seen any reply." [20] Darwin's daughter Henrietta Litchfield also called the story a fabrication, saying "I was present at his deathbed. Lady Hope was not present during his last illness, or any illness. I believe he never even saw her, but in any case she had no influence over him in any department of thought or belief. He never recanted any of his scientific views, either then or earlier. We think the story of his conversion was fabricated in the U.S.A. The whole story has no foundation whatever."[21]

See also

References

- Gonzalez, Justo (1984). The Story of Christianity Vol.1. Harper Collins. p. 176. ISBN 0-06-063315-8.

- "Eusebius of Nicomedia". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

- Smithsonian Part Four - Constantine and the Christian Faith on YouTube

- Hutton, Ronald (1989). Charles II: King of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Oxford University Press. pp. 443, 456. ISBN 0-19-822911-9.

- "Jean de La Fontaine Biography - Infos - Art Market". www.jean-delafontaine.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Sante De Sanctis (1999). Religious Conversion: A Bio-psychological Study. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-21111-6.

- King, Nelson (5 August 2009). "Alan Napier MacNab". Soldier, Statesman, and Freemason Part 3. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Dooner, Alfred (1942–1943), "The Conversion of Sir Allan MacNab, Baronet (1798–1862)", Canadian Catholic Historical Association Report, 10: 47–64, archived from the original on 10 February 2009, retrieved 4 January 2010

- "The Vatican wakes up to the wisdom of Oscar Wilde". independent.co.uk. 17 July 2009. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- J. Killeen (20 October 2005). The Faiths of Oscar Wilde: Catholicism, Folklore and Ireland. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-50355-7.

- Pendergast, Martin (17 July 2009). "The Catholic church learns to love Oscar Wilde - Martin Pendergast". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- McQueen, Joseph (1 December 2017). "Oscar Wilde's Catholic Aesthetics in a Secular Age". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 57 (4): 865–886. doi:10.1353/sel.2017.0038.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Taylor, Jerome (17 July 2009). "The Vatican wakes up to the wisdom of Oscar Wilde – Europe, World". London: The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- "Oscar Wilde: The Final Scene". Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- McCracken, Andrew. "The Long Conversion of Oscar Wilde". Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- Nicholas Frankel (16 October 2017). Oscar Wilde: The Unrepentant Years. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-98202-4.

- Maria J. Cirurgião, “Last Farewell and First Fruits: The Story of a Modern Poet.” Lay Witness (June 2000).

- Peter Brazeau, Parts of a World: Wallace Stevens Remembered, New York, Random House, 1983, p. 295

- "The Lady Hope Story: A Widespread Falsehood". Stephenjaygould.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- "Lady Hope Story". Talkorigins.org. 23 February 1922. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

External links

| Look up deathbed conversion in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |