Dactylanthus taylorii

Dactylanthus taylorii, commonly known as wood rose,[3] is a fully parasitic flowering plant, the only one endemic to New Zealand. The host tree responds to the presence of Dactylanthus by forming a burl-like structure that resembles a fluted wooden rose (hence the common name). When the flowers emerge on the forest floor, they are pollinated by a ground-foraging species of native bat.

| Dactylanthus taylorii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Santalales |

| Family: | Balanophoraceae |

| Genus: | Dactylanthus Hook.f. |

| Species: | D. taylorii |

| Binomial name | |

| Dactylanthus taylorii | |

Description

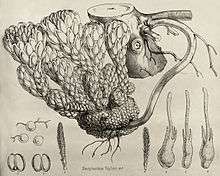

Dactylanthus taylorii is a round warty tuber-like stem (up to 50 cm wide) or haustorium with no roots, which draws nutrients from the roots of its host.[4] Its leaves do not photosynthesise, and are reduced to floral bracts.[3] Some plants have been aged in excess of 30 years old.[4] Dactylanthus prefers damp but not waterlogged soil, and is often found at the head of small streams. It parasitises about 30 species of native hardwood trees and shrubs, preferring those growing in secondary forest on the margin of mature podocarp forest. Common hosts include pate or seven-finger (Schefflera digitata), five-finger (Pseudopanax arboreus), lemonwood (Pittosporum eugenioides), and putaputaweta (Carpodetus serratus).[3]

Plants are either male or female. They flower between February and May[4] and are primarily pollinated by the native short-tailed bat.[5] Analysis of fossil coprolites suggest the kakapo (Strigops habroptilus), a flightless nocturnal parrot, was also a pollinator.[6] Pollinated plants produce fruits slightly under 2 mm (0.079 in) long.[1] The nectar exudes a musky smell that resembles mammalian sweat.[7][8] Introduced mice and rats also pollinate them, although rats tend to destroy them.

Wood rose

The plant takes its common name from the attachment point between tuber and host. The host's roots expand to form a fluted disk, resembling a flower.[4] This growth was once dug up in the thousands, incidentally killing the Dactylanthus, and sold as a collectable curio. It is illegal to collect wood roses from public land, and harvesting this threatened species is strongly discouraged.[4]

Taxonomy and naming

Dactylanthus taylorii was first discovered by Europeans in March 1845, when Rev. Richard Taylor came across it 12 km south of Raetihi.[3] In 1856 Taylor took a specimen to Joseph Hooker in England, who formally described the species in 1859.[9] The genus name is derived from the Greek δάκτυλος (dáktulos), “finger”, and ἄνθος (ánthos), “flower”. The specific epithet (taylorii, originally Taylori) honours Rev. Taylor.[9] It is the only species in the genus.

Taylor stated that the Māori name for wood rose was pua reinga (more grammatically, pua o Te Rēinga, "flower of the underworld", poetically rendered by Hooker as "flower of Hades").[9] Hill noted that at least in the Taupo region this name referred to a different parasitic plant, Thismia,[10] and claimed the Māori name for Dactylanthus was waewae atua, "feet or toes of the spirits/gods".[11]

The closest relative of Dactylanthus is Hachettea from New Caledonia. Along with Mystropetalon from South Africa, they comprise the Southern Hemisphere group Mystropetalaceae. All three are holoparasites, lacking chlorophyll, and are descended from hemiparasitic root parasites which could photosynthesise.[12]

Distribution

Dactylanthus is currently found only in the North Island, although there is evidence from fossil pollen it lived recently in the northern South Island.[3] It ranges from Puketi Forest in Northland through the Coromandel Peninsula as far south as Mt Bruce, and from Mt Taranaki to Te Araroa on the East Coast. It also lives on Little Barrier Island.[4] The plant is cryptic, hence hard to survey, but more than a few thousand in existence is unlikely.[4] Many sites likely are known only to collectors, as the woody growth has commercial value.

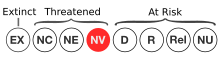

Conservation status

Dactylanthus is regarded, as of 2012, as Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable. The New Zealand Department of Conservation started a recovery plan in 1995.[13] The wood rose is under threat from harvesting by collectors, browsing by possums, rats, pigs and deer, habitat loss, and the rarity of its pollinators and seed dispersers.[1][4] Control of the browsing mammals that feed on Dactylanthus, especially possums and kiore, is one conservation strategy. Another is to enclose the plants in protective cages. Because cages also exclude the plant's pollinators, its flowers then need to be hand-pollinated, and the resulting seed set turns out to be no better than in uncaged plants.[14] Dactylanthus has recently been successfully translocated in the wild by sown seeds in closed-canopy forest.[15]

References

- "Dactylanthus taylorii". New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "Dactylanthus taylorii Hook.f., 1859 [as taylori]". New Zealand Organisms Register. Landcare Research New Zealand. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Ecroyd, Chris E. (1996). "The ecology of Dactylanthus taylorii and threats to its survival". New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 20 (1): 81–100. JSTOR 24053736.

- "Dactylanthus / pua o te reinga" (PDF). Department of Conservation, Waikato Conservancy. 2006. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Ecroyd, C.E. (1994). "Location of short-tailed bats using Dactylanthus" (PDF). Conservation Advisory Science Notes (98).

- Wood, Jamie R.; Wilmshurst, Janet M.; Worthy, Trevor H.; Holzapfel, Avi S.; Cooper, Alan (2012). "A lost link between a flightless parrot and a parasitic plant and the potential role of coprolites in conservation paleobiology". Conservation Biology. 26 (6): 1091–1099. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01931.x. ISSN 1523-1739. PMID 23025275.

- Ecroyd, Chris E; Franich, Robert A.; Kroese, Hank W.; Steward, Diane (1995). The use of Dactylanthus nectar as a lure for possums and bats. Science for Conservation. Wellington, N.Z.: NZ Dept of Conservation.

- Naish, Darren (18 April 2007). "The most terrestrial of bats". Tetrapod Zoology. Sciblogs. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1859). "On a new genus of Balanophorae from New Zealand and two new species of Balanophora". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 22 (4): 425–426. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1856.tb00114.x. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- Hill, H. (1926). "Dactylanthus Taylori, Order Balanophoreae; Tribe Synomorieae" (PDF). Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. 56: 87–90.

- Hill, H. (1908). "On Dactylanthus Taylori". Transactions of the New Zealand Institute. 41: 437–440.

- Su, Huei-Jiun; Hu, Jer-Ming; Anderson, Frank E.; Der, Joshua P.; Nickrent, Daniel L. (2015). "Phylogenetic relationships of Santalales with insights into the origins of holoparasitic Balanophoraceae". Taxon. 64 (3): 491–506. doi:10.12705/643.2. S2CID 92132324.

- Department of Conservation (2005). "Dactylanthus taylorii recovery plan, 2004–14" (PDF). Threatened Species Recovery Plan. 56. Retrieved 19 Feb 2016.

- Ferreira, S.M. (2005). "Individual-level management trade-offs for populations of Dactylanthus taylorii (Balanophoraceae)". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 43 (2): 415–424. doi:10.1080/0028825x.2005.9512964. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Holzapfel, Sebastian A.; Dodgson, John; Rohan, Maheshwaran (2015). "Successful translocation of the threatened New Zealand root-holoparasite Dactylanthus taylorii (Mystropetalaceae)". Plant Ecology. 217 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1007/s11258-015-0556-7.

External links

- New Zealand Department of Conservation Dactylanthus information

- Radio New Zealand: Our Changing World programme about Dactylanthus, with photographs, audio and video.

- Dactylanthus discussed on RadioNZ Critter of the Week, 19 February 2016