D. H. Turner

Derek Howard Turner (15 May 1931 – 1 August 1985) was an English museum curator and art historian who specialised in liturgical studies and illuminated manuscripts. He worked at the British Museum and the British Library from 1956 until his death, focusing on exhibitions, scholarship, and loans.

D. H. Turner | |

|---|---|

Turner escorting Queen Elizabeth II around the exhibition "The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art" in 1985 | |

| Born | Derek Howard Turner 15 May 1931 Northampton, England |

| Died | 1 August 1985 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Curator; art historian |

| Years active | 1956–1985 |

| Known for | Studies of liturgy and illuminated manuscripts |

Following several years spent working at a hospital and living at an Anglican Benedictine abbey, Turner found employment in the British Museum's Department of Manuscripts at the age of 25. Serving first as assistant keeper, and later as deputy keeper, within two years of his hiring he helped the museum select manuscripts for purchase from the Dyson Perrins collection and organised his first exhibition; in the 1960s he also took teaching posts at the universities of Cambridge and East Anglia.

Turner moved to the British Library when custodianship of the museum's library elements changed in 1973. At the library he helped oversee several major exhibitions, and organise the international loans of significant documents. He was closely involved with the lending of a copy of Magna Carta for the 1976 United States Bicentennial celebrations, and in succeeding years helped loan several medieval manuscripts for the first time in half a millennium. Through his work the Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander returned to Bulgaria for the first time since the 1300s, and the Moutier-Grandval Bible returned to Switzerland, its home throughout the Middle Ages.

Early life and education

D. H. Turner was born on 15 May 1931 in Northampton, England.[1] An only child, he was born to the World War I veteran Maurice Finnemore Turner and his wife Eva (née Howard).[1] After attending Winchester House School in Brackley, in the summer of 1945 Turner was sent on scholarship to Harrow.[1] In 1950 a Harrow scholarship to read modern history sent him to Hertford College at the University of Oxford; he graduated in the summer of 1953.[1]

Before his employment at the British Museum, Turner worked at a hospital, and spent time at the Anglican Benedictine abbey Nashdom.[1] There he both studied and practised liturgy, and met the medieval music specialist Dom Anselm Hughes.[1]

Career

Turner worked at the British Museum from 1956 until 1973, and at the British Library from 1973 until his 1985 death, the move occasioned only by the deaccession of the museum's library elements in favour of the new institution.[2] From assistant keeper he rose to deputy keeper.[2] He focused on medieval liturgical studies and illuminated manuscripts, overseeing their exhibition, acquisition, and loans.[3] Particularly while an assistant keeper he also focused on scholarship, seeing many articles published and teaching part-time at the Universities of Cambridge and East Anglia.[4]

At the British Museum

D. H. Turner began work as an assistant keeper of the Department of Manuscripts at the British Museum on 3 December 1956.[1] Influenced by his time at Nashdom, he specialised in medieval liturgical studies, and influenced by the lavish decoration of liturgical manuscripts, he likewise studied illuminated manuscripts.[1]

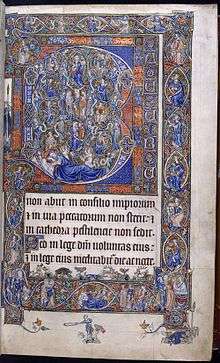

In 1958 Turner organised his first exhibition, showcasing a collection of Byzantine manuscripts.[1] The same year he helped the museum select illuminated manuscripts to purchase from the collection of Charles William Dyson Perrins, before it was offered publicly. Including two bequests by Perrins, and eight purchases at a collective and below market £37,250, the museum acquired ten of the collection's 154 manuscripts.[5] These included the Gorleston Psalter, the Khamsa of Nizami, and the book of hours by William de Brailes,[5] and were the subject of a paper by Turner the following year.[1][6] Upon the December 1960 resignation of Julian Brown, a coauthor of the paper who left for the Chair of Palaeography at King's College London, Turner assumed responsibility over the museum's collection of illustrated manuscripts.[2]

In his new role heading the collection of illustrated manuscripts, Turner focused on scholarship.[7] His resulting publications ranged from those that his colleagues described as "extremely erudite", to those aimed at a popular audience.[7] In the mid 1960s Turner began teaching art history part-time at the University of Cambridge and the University of East Anglia, repurposing as teaching material two booklets he had authored on English Gothic and European Romanesque illumination.[7] He also assumed the chairmanship of two organisations involved with liturgical studies, the Plainsong and Medieval Music Society in 1964, and the Henry Bradshaw Society in 1967.[7] Turner was promoted to deputy keeper in 1972, following the retirements of the keeper Theodore Cressy Skeat and the senior deputy keeper Cyril Ernest Wright.[7]

At the British Library

A year after Turner's promotion to deputy keeper, the Department of Manuscripts was subsumed into the British Library, and him with it; subsequently his role shifted to the curation of exhibitions, and to responsibility over loans from the collection of manuscripts.[8] In the former role Turner helped oversee three major exhibitions: The Christian Orient in 1978, The Benedictines in Britain in 1980, and, with Janet Backhouse and Leslie Webster,[9] The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art in 1984.[7] The Benedictines in Britain, attended by the leader of each of the country's Benedictine communities, "allowed him", his colleagues wrote, "to give full rein to one of his favourite pastimes, creating a guest list on which every style and title should appear with absolute accuracy. He spent many happy hours in the bookstacks, consulting directories in pursuit of this perfection!"[7]

Turner was also responsible for facilitating the international loans of important manuscripts.[10] In the process he enjoyed interacting with the Foreign Office—and poring over abstruse indemnity arrangements—leading to the loan of Magna Carta to Washington, D.C. for the 1976 United States Bicentennial celebrations.[10] The following year he helped loan the Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander to Sofia, Bulgaria, where it received national publicity; it had last been in the country in the fourteenth century.[10] In 1979 he helped lend the Leningrad Bede to the Bede Monastery Museum in Jarrow and to Bloomsbury, and in 1981 Turner saw the Moutier-Granval Bible return to Jura, Switzerland, its home throughout the Middle Ages.[10]

Personal life

Turner was described as "[a]n intensely sensitive spirit, ... for whom living was no easy matter";[11] colleagues remembered him as "a memorable—if unpredictable—character."[1] An only child unused to close-knit family life, he enjoyed the company of those a generation or profession removed from him over that of his peers and contemporaries.[12] Learning that the son of a commuting acquaintance was interested in Anglo-Saxon literature, Turner invited the two to the library to handle the Beowulf manuscripts,[12] but among colleagues he had "a not undeserved reputation for being difficult and could chill the blood of the more timid."[13] He nevertheless shared a close working relationship with Janet Backhouse, also of the British Museum and later Library, and introduced her to the exhibition and loans of manuscripts.[13]

The unexpected death of his mother in 1966–1967, and his father's subsequent move into a nursing home, precipitated what Backhouse termed a "radical change" in Turner's life.[14] He moved from his bedsitter by Kew Gardens to his parents' flat in Henley-on-Thames, his dress became flamboyant, and his published output declined.[14] Much of his social interaction came at the museum and library; once offered several months leave by keeper of manuscripts Daniel Waley to work on a Yates Thompson manuscript catalogue, Turner declined, lest he sacrifice his daily interactions with colleagues.[15] Turner died suddenly on 1 August 1985.[1]

Publications

Turner published widely, beginning soon after his employment at the British Museum.[1] After his promotion to deputy keeper his output dwindled, and primarily focused on current exhibitions and recent acquisitions.[14]

Books

- Turner, Derek H. (1962). The Missal of the New Minster, Winchester (Le Harve, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 330). Henry Bradshaw Society Publications. XCIII. London: Faith Press.

- Turner, Derek H. (1965). Early Gothic Illuminated Manuscripts in England. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Turner, Derek H. (1965). Reproductions from Illuminated Manuscripts. Series V. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Turner, Derek H. & Scheele, Margaret (1965). English Book illustration, 966–1846. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Dodwell, Charles R. & Turner, Derek H. (1965). Reichenau Reconsidered: a Re-assessment of the Place of Reichenau in Ottonian Art. Warburg Institute Surveys. 2. London: Warburg Institute, University of London.

- Turner, Derek H. (1966). Romanesque Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Museum. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Turner, Derek H. (1967). Illuminated Manuscripts Exhibited in the Grenville Library. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Turner, Derek H. (1971). The Claudius Pontificals: (from Cotton MS. Claudius A. iii in the British Museum). Henry Bradshaw Society Publications. XCVII. London: Henry Bradshaw Society. ISBN 0-9501009-2-7.

- Turner, Derek H.; Stockdale, Rachel; Jebb, Dom P. & Rogers, David, eds. (1980). The Benedictines in Britain. London: British Library. ISBN 0-904654-47-8.

- Turner, Derek H. (1983). The Hastings Hours: A 15th-Century Flemish Book of Hours made for William, Lord Hastings, now in the British Library, London. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Backhouse, Janet; Turner, Derek H. & Webster, Leslie, eds. (1984). The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art, 966–1066. London: British Museum Publications. ISBN 978-0-7141-0532-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Articles

- Turner, Derek H. (1959). "An Early Thirteenth Century Premonstratensian Gradual". Analecta Praemonstratensia. XXXV (3–4): 193–197.

- Turner, Derek H. (1960). "The Crowland Gradual: An English Benedictine Manuscript". Ephemerides Liturgicae. LXXIV: 168–174. ISSN 0013-9505.

- Turner, Derek H. (1960). "The Prayer-book of Archbishop Arnulph II of Milan". Revue Bénédictine. Maredsous Abbey. LXX (2): 360–392. doi:10.1484/J.RB.4.00421. ISSN 0035-0893.

- Brown, Thomas J.; Meredith-Owens, Glyn M. & Turner, Derek H. (January 1961). "Manuscripts from the Dyson Perrins Collection". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXIII (2): 27–38. JSTOR 4422661.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, Derek H. (1962). "The Bedford Hours and Psalter". Apollo. LXXVI: 265–270. ISSN 0003-6536.

- Turner, Derek H. (March 1962). "The 'Ǒdalricus Peccator' Manuscript in the British Museum". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXV (1–2): 11–16. JSTOR 4422728.

- Turner, Derek H. (1962). "A Twelfth Century Psalter from Camaldoli". Revue Bénédictine. Maredsous Abbey. LXXII (1–2): 109–130. doi:10.1484/J.RB.4.01566. ISSN 0035-0893.

- Turner, Derek H. (1962). "The Siegburg Lectionary". Scriptorium. XVI: 16–27.

- Turner, Derek H. (Autumn 1964). "The Penwortham Breviary". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXVIII (3–4): 85–88. JSTOR 4422861.

- Turner, Derek H. (1964). "The Evesham Psalter". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Warburg Institute. XXVII: 23–41. JSTOR 750510.

- Turner, Derek H. (Summer 1965). "Illumination from the School of Niccolò da Bologna". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXIX (3–4): 84–89. JSTOR 4422897.

- Turner, Derek H. (1965). "The 'Reichenau' Sacramentaries at Zurich and Oxford". Revue Bénédictine. Maredsous Abbey. LXXV (3–4): 240–276. doi:10.1484/J.RB.4.00635. ISSN 0035-0893.

- Turner, Derek H. (Spring 1966). "From the Library of Eric George Millar". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXX (3–4): 80–88. JSTOR 4422931.

- Turner, Derek H. (Autumn 1968). "A Bibliography of Eric Millar". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXXIII (1–2): 7–16. JSTOR 4423014.

- Turner, Derek H.; Borrie, Michael A. F.; Blackhouse, Janet & Stratford, Jenny (Autumn 1968). "The Eric Millar Bequest to the Department of Manuscripts". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXXIII (1–2): 16–52. JSTOR 4423015.

- Turner, Derek H. (Autumn 1968). "The Development of Maître Honoré". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXXIII (1–2): 53–65. JSTOR 4423016.

- Turner, Derek H. (Autumn 1969). "Two Rediscovered Miniatures of the Oscott Psalter". The British Museum Quarterly. British Museum. XXXIV (1–2): 10–19. JSTOR 4423038.

- Turner, Derek H. (1971). "Sacramentaries of Saint Gall in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries". Revue Bénédictine. Maredsous Abbey. LXXXI (3–4): 186–215. doi:10.1484/J.RB.4.00768. ISSN 0035-0893.

- Brown, Thomas J. & Turner, Derek H. (May 1972). "Francis Wormald, 1904–72". Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. Institute of Historical Research. XLV (111): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1972.tb01447.x. ISSN 0041-9761.

- Turner, Derek H. (October 1973). "Principal Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts in the British Library". The British Museum Society Bulletin. British Museum Society (14): 10–13.

- Turner, Derek H. (Spring 1976). "The Wyndham Payne Crucifixion" (PDF). The British Library Journal. British Library. 2 (1): 8–26.

- Turner, Derek H. (April 1976). "The Customary of the Shrine of St Thomas Becket". The Canterbury Chronicle. The Friends of Canterbury Cathedral (70): 16–22.

- Turner, Derek H. (1984). "The Rutland Psalter". National Art-Collections Fund Review: 94–97.

- Turner, Derek H. (December 1984). "The Anglo-Saxon Achievement". History Today. XXXIV (12): 58–59. ISSN 0018-2753.

Chapters

- Turner, Derek H. (1961). "Note on the Music". In Ullmann, Walter (ed.). Liber Regie Capelle: A Manuscript in the Biblioteca Publica, Evora. Henry Bradshaw Society Publications. XCII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–51.

- Turner, Derek H. (1962). "A 10th–11th Century Noyon Sacramentary". In Cross, Frank L. (ed.). Studia Patristica: Papers Presented to the Third International Conference on Patristic Studies Held at Christ Church, Oxford, 1959. V. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. pp. 143–151.

- Turner, Derek H. (1970). "Manuscript Illumination". In Deuchler, Florens (ed.). The Year 1200. II. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 133–139.

- Turner, Derek H. (1978). "The Orthodox Church". The Christian Orient: An Exhibition in the King's Library from 5 July to 24 September 1978. London: British Museum Publications. pp. 13–21. ISBN 0-7141-0666-6.

- Turner, Derek H. (1980). "Hughes, Anselm". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. VIII. London: Macmillan. pp. 765–766. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Turner, Derek H. (1981). "Customary of the Shrine of St Thomas Becket, Canterbury 1428". In de Hamel, Christopher & Linenthal, Richard A. (eds.). Fine Books and Book Collecting: Books and Manuscripts Acquired from Alan G. Thomas and Described by his Customers on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday. Leamington Spa: J. Hall. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Turner, Derek H. (1981). "La Bible de Moutier-Grandval et la Grande Bretagne". Jura, Treize Siècles de Divilisation Chrétienne: Le Livre de L'exposition. Delémont, du 16 Mai au 20 Sept. 1981. Delémont: Musée Jurassien d'Art et d'Histoire. pp. 38–39.

- Turner, Derek H. (1983). "Introduction". In Kren, Thomas & Backhouse, Janet (eds.). Renaissance Painting in Manuscripts: Treasures from the British Library. London: British Library, Reference Division Publications. pp. ix–xii. ISBN 0-933920-51-2.

References

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, p. 111.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, pp. 111–112.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, pp. 111–113.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, pp. 111–114.

- Brown, Meredith-Owens & Turner 1961, p. 27.

- Brown, Meredith-Owens & Turner 1961.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, p. 112.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, pp. 112–113.

- Backhouse, Turner & Webster 1984.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, p. 113.

- The Times 1985.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, p. 115.

- The Times 2004.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, p. 114.

- Backhouse & Jones 1987, p. 116.

Bibliography

- Backhouse, Janet & Jones, Shelley (Autumn 1987). "D. H. Turner (1931–1985): A Portrait" (PDF). The British Library Journal. British Library. 13 (1): 111–117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Janet Backhouse: Scholar at the British Museum Who Brought the World of Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts to a Wider Public". Obituaries. The Times (68270). London. 29 December 2004. p. 43.

- Kren, Thomas (Autumn 1996). "Some Newly Discovered Miniatures by Simon Marmion and his Workshop" (PDF). The British Library Journal. British Library. 22 (2): 193–220. JSTOR 42554431.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Mr. D. H. Turner". Obituary. The Times (62215). London. 13 August 1985. p. 12.