Tranexamic acid

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a medication used to treat or prevent excessive blood loss from major trauma, postpartum bleeding, surgery, tooth removal, nosebleeds, and heavy menstruation.[1][2] It is also used for hereditary angioedema.[1][3] It is taken either by mouth or injection into a vein.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | \ˌtran-eks-ˌam-ik-\ |

| Trade names | Cyklokapron, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, injection, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 34% |

| Elimination half-life | 3.1 h |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.471 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

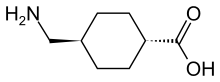

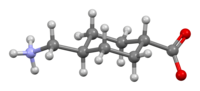

| Formula | C8H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 157.21 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects are rare.[3] Some include changes in color vision, blood clots, and allergic reactions.[3] Greater caution is recommended in people with kidney disease.[4] Tranexamic acid appears to be safe for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[3][5] Tranexamic acid is in the antifibrinolytic family of medications.[4]

Tranexamic acid was first made in 1962 by Japanese researchers Shosuke and Utako Okamoto.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] Tranexamic acid is available as a generic medication[8]

Medical uses

Tranexamic acid is frequently used following major trauma.[9] Tranexamic acid is used to prevent and treat blood loss in a variety of situations, such as dental procedures for hemophiliacs, heavy menstrual bleeding, and surgeries with high risk of blood loss.[10][11]

Trauma

Tranexamic acid has been found to decrease the risk of death in people who have significant bleeding due to trauma.[12][13] Its main benefit is if taken within the first three hours.[14] It has been shown to reduce death due to any cause and death due to bleeding.[15] Further studies are assessing the effect of tranexamic acid in isolated brain injury.[16] Given within three hours of a head injury it also decreases the risk of death.[17]

Vaginal bleeding

Tranexamic acid is used to treat heavy menstrual bleeding.[11] When taken by mouth it both safely and effectively treats regularly occurring heavy menstrual bleeding and improves quality of life.[18][19][20] Another study demonstrated that the dose does not need to be adjusted in females who are between ages 12 and 16.[18]

Child birth

Tranexamic acid is used after delivery to reduce bleeding, often with oxytocin.[21] Death due to postpartum bleeding was reduced in women receiving tranexamic acid.[2]

Surgery

- Tranexamic acid is used in orthopedic surgery to reduce blood loss, to the extent of reducing or altogether abolishing the need for perioperative blood collection. It is of proven value in clearing the field of surgery and reducing blood loss when given before or after surgery. Drain and number of transfusions are reduced.[22][23][24]

- In surgical corrections of craniosynostosis in children it reduces the need for blood transfusions.[25]

- In spinal surgery (e.g., scoliosis), correction with posterior spinal fusion using instrumentation, to prevent excessive blood loss.[26]

- In cardiac surgery, both with and without cardiopulmonary bypass (e.g., coronary artery bypass surgery), it is used to prevent excessive blood loss.[22]

Dentistry

In the United States, tranexamic acid is FDA approved for short-term use in people with severe bleeding disorders who are about to have dental surgery.[27] Tranexamic acid is used for a short period of time before and after the surgery to prevent major blood loss and decrease the need for blood transfusions.[28]

Tranexamic acid is used in dentistry in the form of a 5% mouth rinse after extractions or surgery in patients with prolonged bleeding time; e.g., from acquired or inherited disorders.[29]

Hematology

There is not enough evidence to support the routine use of tranexamic acid to prevent bleeding in people with blood cancers.[30] However, there are several trials that are currently assessing this use of tranexamic acid.[30] For people with inherited bleeding disorders (e.g. von Willebrand's disease), tranexamic acid is often given.[16] It has also been recommended for people with acquired bleeding disorders (e.g., directly acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs)) to treat serious bleeding.[31]

Nosebleeds

The use of tranexamic acid, applied directly to the area that is bleeding or taken by mouth, appears useful to treat nose bleeding compared to packing the nose with cotton pledgets alone.[32][33][34] It decreases the risk of rebleeding within 10 days.[35]

Other uses

- Tentative evidence supports the use of tranexamic acid in hemoptysis.[36][37]

- In hereditary angioedema[38]

- In hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia - Tranexamic acid has been shown to reduce frequency of epistaxis in patients suffering severe and frequent nosebleed episodes from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.[39]

- In melasma - tranexamic acid is sometimes used in skin whitening as a topical agent, injected into a lesion, or taken by mouth, both alone and as an adjunct to laser therapy; as of 2017 its safety seemed reasonable but its efficacy for this purpose was uncertain because there had been no large scale randomized controlled studies nor long term follow-up studies.[40][41]

- In hyphema - Tranexamic acid has been shown to be effective in reducing risk of secondary hemorrhage outcomes in people with traumatic hyphema.[42]

Experimental uses

Tranexamic acid might alleviate neuroinflammation in some experimental settings.[43]

Contraindications

- Allergic to tranexamic acid

- History of seizures

- History of venous or arterial thromboembolism or active thromboembolic disease

- Severe kidney impairment due to accumulation of the medication, dose adjustment is required in mild or moderate kidney impairment[1]

Adverse effects

Side effects are rare.[3] Some include changes in color vision, blood clots, and allergic reactions.[3]

Blood clots may include venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism), anaphylaxis.[18] These rare side effects were reported in post marketing experience and frequencies cannot be determined.[18] Despite the mode of action, large studies of the use of tranexamic acid have not shown an increase in the risk of venous or arterial thrombosis.[44]

Special populations

- Tranexamic acid is categorized as pregnancy category B. No harm has been found in animal studies.[18]

- Small amounts appears in breast milk if taken during lactation.[18] If it is required for other reasons, breastfeeding may be continued.[45]

- In kidney impairment, tranexamic acid is not well studied. However, due to the fact that it is 95% excreted unchanged in the urine, it should be dose adjusted in patients with renal impairment.[18]

- In liver impairment, dose change is not needed as only a small amount of the drug is metabolized through the liver.[18]

Mechanism of action

Tranexamic acid is a synthetic analog of the amino acid lysine. It serves as an antifibrinolytic by reversibly binding four to five lysine receptor sites on plasminogen. This reduces conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, preventing fibrin degradation and preserving the framework of fibrin's matrix structure.[18] Tranexamic acid has roughly eight times the antifibrinolytic activity of an older analogue, ε-aminocaproic acid. Tranexamic acid also directly inhibits the activity of plasmin with weak potency (IC50 = 87 mM),[46] and it can block the active-site of urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) with high specificity (Ki = 2 mM) among all the serine proteases.[47]

Society and culture

Tranexamic acid was first synthesized in 1962 by Japanese researchers Shosuke and Utako Okamoto.[6] It has been included in the WHO list of essential medicines.[48]

Cost

TXA is inexpensive and treatment would be considered highly cost effective in high, middle and low income countries.[49]

Brand names

Tranexamic acid is marketed in the U.S. and Australia in tablet form as Lysteda and in Australia and Jordan it is marketed in an IV form and tablet form as Cyklokapron, in the UK as Cyclo-F and Femstrual, in Asia as Transcam, in Bangladesh as Tracid, in India as Pause, in Pakistan as Transamin, in South America as Espercil, in Japan as Nicolda, in France, Belgium and Romania as Exacyl and in Egypt as Kapron. In the Philippines, its capsule form is marketed as Hemostan and In Israel as Hexakapron.

Approval

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tranexamic acid oral tablets (brand name Lysteda) for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding on 13 November 2009.

In March 2011 the status of tranexamic acid for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding was changed in the UK, from PoM (Prescription only Medicines) to P (Pharmacy Medicines)[50] and became available over the counter in UK pharmacies under the brand names of Cyklo-F and Femstrual, initially exclusively for Boots pharmacy, which has sparked some discussion about availability.[51] (In parts of Europe it had then been available OTC for over a decade.) Regular liver function tests are recommended when using tranexamic acid over a long period of time.[52]

References

- British national formulary: BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 170. ISBN 9780857111562.

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators (May 2017). "Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 389 (10084): 2105–2116. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30638-4. PMC 5446563. PMID 28456509.

- "Cyklokapron Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. September 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Tranexamic Acid Injection - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Tranexamic acid Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Geoff Watts (2016). "Obituary Utako Okamoto". The Lancet. 387 (10035): 2286. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30697-3. PMID 27308678.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 415. ISBN 9781284057560.

- Binz S, McCollester J, Thomas S, Miller J, Pohlman T, Waxman D, Shariff F, Tracy R, Walsh M (2015). "CRASH-2 Study of Tranexamic Acid to Treat Bleeding in Trauma Patients: A Controversy Fueled by Science and Social Media". Journal of Blood Transfusion. 2015: 874920. doi:10.1155/2015/874920. PMC 4576020. PMID 26448897.

- Melvin JS, Stryker LS, Sierra RJ (December 2015). "Tranexamic Acid in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 23 (12): 732–40. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00223. PMID 26493971.

- Tengborn L, Blombäck M, Berntorp E (February 2015). "Tranexamic acid--an old drug still going strong and making a revival". Thrombosis Research. 135 (2): 231–42. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.012. PMID 25559460.

- Cherkas D (November 2011). "Traumatic hemorrhagic shock: advances in fluid management". Emergency Medicine Practice. 13 (11): 1–19, quiz 19–20. PMID 22164397. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- "Drug will save lives of accident victims, says study". BBC News. 2010. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Napolitano LM, Cohen MJ, Cotton BA, Schreiber MA, Moore EE (June 2013). "Tranexamic acid in trauma: how should we use it?". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 74 (6): 1575–86. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318292cc54. PMID 23694890.

- Ker K, Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats TJ (May 2015). "Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD004896. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004896.pub4. PMID 25956410.

- "Tranexamic acid". Clinical Transfusion. International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT).

- CRASH-3 trial collaborators (October 2019). "Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial". The Lancet. 394 (10210): 1713–1723. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32233-0. PMC 6853170. PMID 31623894.

- "Lysteda (tranexamic acid) Package Insert" (PDF). accessdata.FDA.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, Gersten JK, Hecht BR, Edlund M, Richter HE, Eder SE, Attia GR, Patrick DL, Rubin A, Shangold GA (October 2010). "Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 116 (4): 865–75. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f20177. PMID 20859150.

- Naoulou B, Tsai MC (May 2012). "Efficacy of tranexamic acid in the treatment of idiopathic and non-functional heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 91 (5): 529–37. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01361.x. PMID 22229782.

- "Postpartum Haemorrhage, Prevention and Management (Green-top Guideline No. 52)". Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists-US. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Henry, David A; Carless, Paul A; Moxey, Annette J; O'Connell, Dianne; Stokes, Barrie J; Fergusson, Dean A; Ker, Katharine (16 March 2011), "Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion", in The Cochrane Collaboration (ed.), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. CD001886, doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001886.pub4, PMC 4234031, PMID 21412876

- Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P, Shakur H, Roberts I (May 2012). "Effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis". BMJ. 344: e3054. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3054. PMC 3356857. PMID 22611164.

- Ker K, Prieto-Merino D, Roberts I (September 2013). "Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of tranexamic acid on surgical blood loss" (PDF). The British Journal of Surgery. 100 (10): 1271–9. doi:10.1002/bjs.9193. PMID 23839785.

- RCPCH. "Evidence Statement Major trauma and the use of tranexamic acid in children Nov 2012" (PDF). Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- Sethna NF, Zurakowski D, Brustowicz RM, Bacsik J, Sullivan LJ, Shapiro F (April 2005). "Tranexamic acid reduces intraoperative blood loss in pediatric patients undergoing scoliosis surgery". Anesthesiology. 102 (4): 727–32. doi:10.1097/00000542-200504000-00006. PMID 15791100.

- "Cyklokapron (tranexamic acid) Product Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- Forbes CD, Barr RD, Reid G, Thomson C, Prentice CR, McNicol GP, Douglas AS (May 1972). "Tranexamic acid in control of haemorrhage after dental extraction in haemophilia and Christmas disease". British Medical Journal. 2 (5809): 311–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5809.311. PMC 1788188. PMID 4553818.

- van Galen, Karin Pm; Engelen, Eveline T.; Mauser-Bunschoten, Evelien P.; van Es, Robert Jj; Schutgens, Roger Eg (19 April 2019). "Antifibrinolytic therapy for preventing oral bleeding in patients with haemophilia or Von Willebrand disease undergoing minor oral surgery or dental extractions". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD011385. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011385.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6474399. PMID 31002742.

- Estcourt LJ, Desborough M, Brunskill SJ, Doree C, Hopewell S, Murphy MF, Stanworth SJ (March 2016). "Antifibrinolytics (lysine analogues) for the prevention of bleeding in people with haematological disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD009733. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009733.pub3. PMC 4838155. PMID 26978005.

- Siegal DM, Garcia DA, Crowther MA (February 2014). "How I treat target-specific oral anticoagulant-associated bleeding". Blood. 123 (8): 1152–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-09-529784. PMID 24385535.

- Ker K, Beecher D, Roberts I (July 2013). Ker K (ed.). "Topical application of tranexamic acid for the reduction of bleeding" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD010562. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010562.pub2. PMID 23881695.

- Logan JK, Pantle H (November 2016). "Role of topical tranexamic acid in the management of idiopathic anterior epistaxis in adult patients in the emergency department". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 73 (21): 1755–1759. doi:10.2146/ajhp150829. PMID 27769971.

- Williams A, Biffen A, Pilkington N, Arrick L, Williams RJ, Smith ME, Smith M, Birchall J (December 2017). "Haematological factors in the management of adult epistaxis: systematic review". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 131 (12): 1093–1107. doi:10.1017/S0022215117002067. PMID 29280698.

- Gottlieb, M; Koyfman, A; Long, B (November 2019). "Tranexamic Acid for the Treatment of Epistaxis". Academic Emergency Medicine. 26 (11): 1292–1293. doi:10.1111/acem.13760. PMID 30933392.

- Moen CA, Burrell A, Dunning J (December 2013). "Does tranexamic acid stop haemoptysis?". Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 17 (6): 991–4. doi:10.1093/icvts/ivt383. PMC 3829500. PMID 23966576.

- Prutsky G, Domecq JP, Salazar CA, Accinelli R (November 2016). "Antifibrinolytic therapy to reduce haemoptysis from any cause". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD008711. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008711.pub3. PMC 6464927. PMID 27806184.

- Flower R, Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM (2007). Rang & Dale's pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-06911-6.

- Klepfish A, Berrebi A, Schattner A (March 2001). "Intranasal tranexamic acid treatment for severe epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia". Archives of Internal Medicine. 161 (5): 767. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.5.767. PMID 11231712.

- Zhou LL, Baibergenova A (September 2017). "Melasma: systematic review of the systemic treatments". International Journal of Dermatology. 56 (9): 902–908. doi:10.1111/ijd.13578. PMID 28239840.

- Taraz M, Niknam S, Ehsani AH (May 2017). "Tranexamic acid in treatment of melasma: A comprehensive review of clinical studies". Dermatologic Therapy. 30 (3): e12465. doi:10.1111/dth.12465. PMID 28133910.

- Gharaibeh A, Savage HI, Scherer RW, Goldberg MF, Lindsley K (January 2019). Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (ed.). "Medical interventions for traumatic hyphema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD005431. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005431.pub4. PMC 6353164. PMID 30640411.

- Atsev, Stanimir; Tomov, Nikola (2020). "Using antifibrinolytics to tackle neuroinflammation". Neural Regeneration Research. 15 (12): 2203. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.284979. ISSN 1673-5374.

- Chornenki, Nicholas L. Jackson; Um, Kevin J.; Mendoza, Pablo A.; Samienezhad, Ashkan; Swarup, Vidushi; Chai-Adisaksopha, Chatree; Siegal, Deborah M. (July 2019). "Risk of venous and arterial thrombosis in non-surgical patients receiving systemic tranexamic acid: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Thrombosis Research. 179: 81–86. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2019.05.003. PMID 31100632.

- "Tranexamic Acid use while Breastfeeding". www.drugs.com. 7 November 2014. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Law RH, Wu G, Leung EW, Hidaka K, Quek AJ, Caradoc-Davies TT, Jeevarajah D, Conroy PJ, Kirby NM, Norton RS, Tsuda Y, Whisstock JC (May 2017). "X-ray crystal structure of plasmin with tranexamic acid-derived active site inhibitors". Blood Advances. 1 (12): 766–771. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2016004150. PMC 5728053. PMID 29296720.

- Wu G, Mazzitelli BA, Quek AJ, Veldman MJ, Conroy PJ, Caradoc-Davies TT, Ooms LM, Tuck KL, Schoenecker JG, Whisstock JC, Law RH (March 2019). "Tranexamic acid is an active site inhibitor of urokinase plasminogen activator". Blood Advances. 3 (5): 729–733. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018025429. PMC 6418500. PMID 30814058.

- "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Guerriero C, Cairns J, Perel P, Shakur H, Roberts I (May 2011). "Cost-effectiveness analysis of administering tranexamic acid to bleeding trauma patients using evidence from the CRASH-2 trial". PLOS ONE. 6 (5): e18987. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618987G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018987. PMC 3086904. PMID 21559279.

- Chapman C (27 January 2011). "Tranexamic Acid to be available OtC". Community pharmacy news, analysis and CPD. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011.

- Chapman C (10 February 2011). "In defence of multiple pharmacies". Community pharmacy news, analysis and CPD. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- Allen H (13 June 2012). "Tranexamic acid for bleeding". Patient UK. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014.

External links

- ISBT information on tranexamic acid

- Tranexamic acid, UK patient information leaflet

- CRASH-2: tranexamic acid and trauma patients

- TXA central; site collating all clinical evidence for tranexamic acid by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

- "Tranexamic Acid". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.